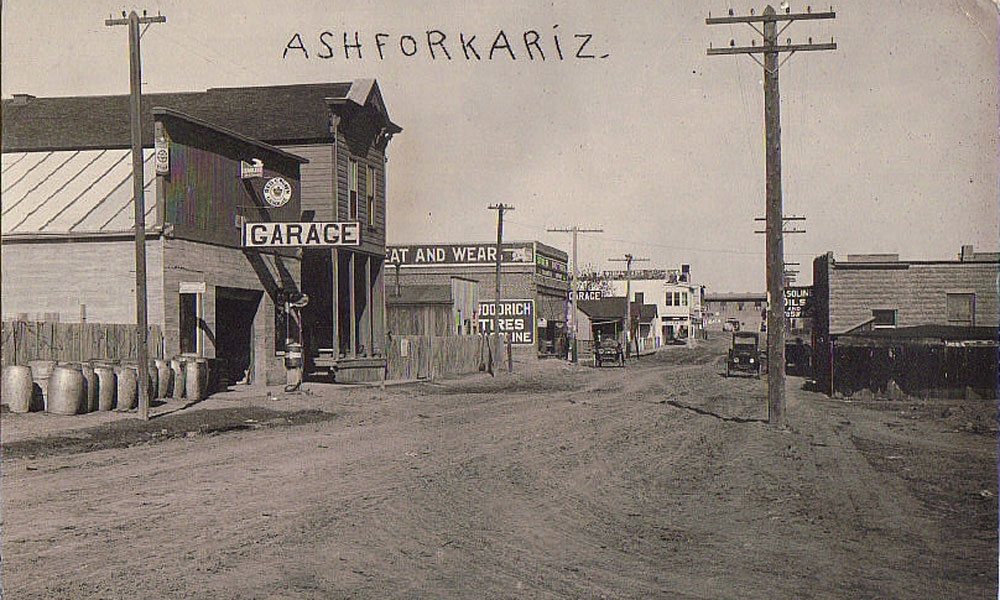

The town of Ash Fork was born in 1882 when the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, which later became the Santa Fe arrived. It was one of five transcontinental railroad lines designed to connect the East Coast with the West.

During the 1890s the town became an important junction when the Santa Fe built a branch line south to Prescott, Wickenburg and Phoenix. It’s still central and southern Arizona’s only railroad link to northern Arizona. Historians refer to this as the official closing of the frontier in Arizona history.

In 1876, Fred Harvey opened the first of his elegant Spanish-style restaurant-hotels at one hundred-mile intervals along the Santa Fe Railroad line. It was said they were spaced that distance so they would keep western traffic from settling in one place where Harvey served his meals.

Ash Fork’s first Harvey House was a wooden structure located on the north side of the tracks facing Cooper Thomas Lewis’ Parlor House Saloon and the Postal Telegraph Store.

On June 17th, 1905 a fire destroyed the depot, hotel, restaurant and water tower in the heart of the business district. It started in the kitchen of the original Harvey House doing $20,000 worth of damage. Railroad officials promised they would build a new Harvey House of steel and concrete much better than the original. Some of the residents were upset because the new building would be 500 feet west of the old one.

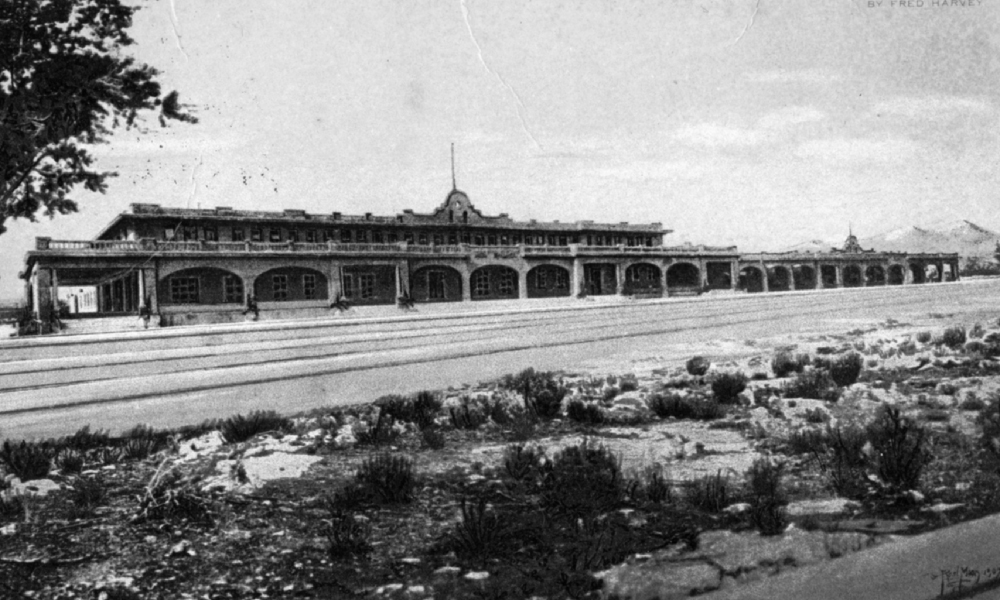

The result was the luxurious Escalante, named for the eighteenth century Spanish padre-explorer, Silvestre Escalante who journeyed into Arizona in 1776. The name was in keeping with the Harvey tradition of naming their establishments after Spanish explorers.

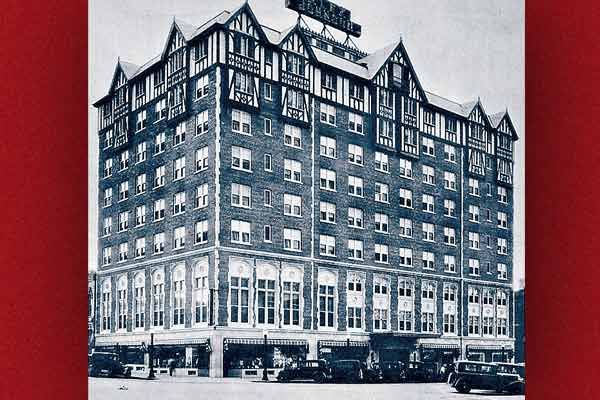

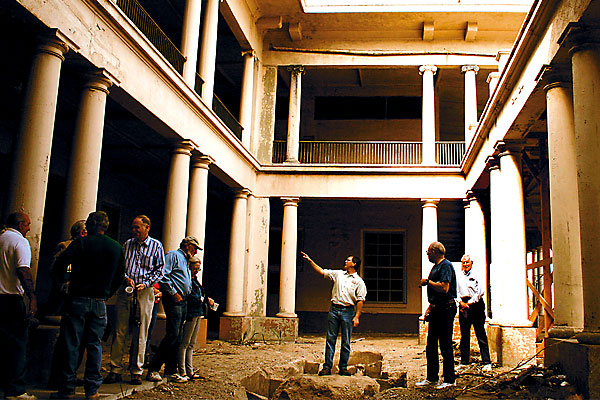

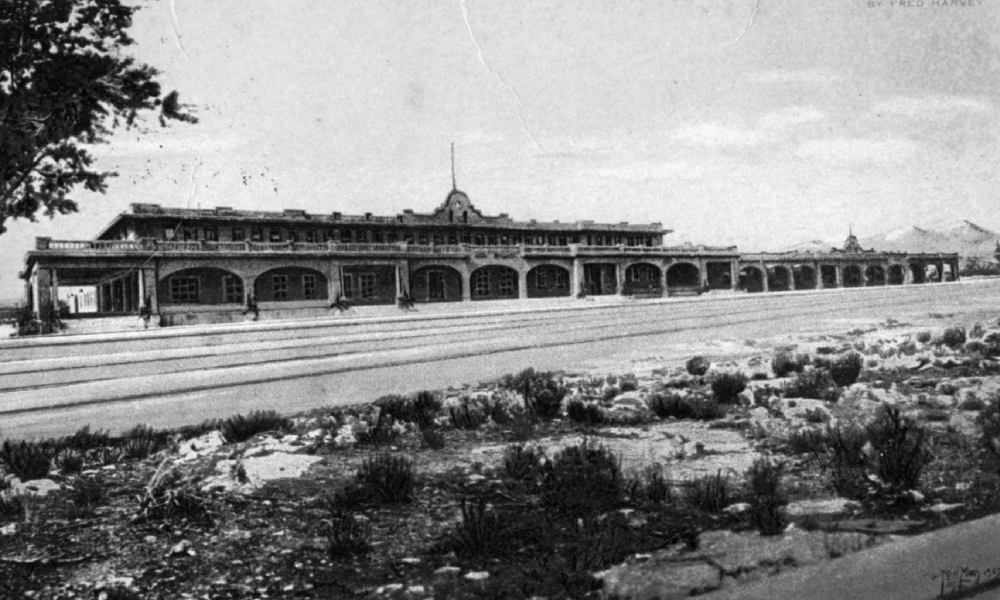

The Escalante, at a cost of $115,000, opened in March, 1907. It was built in and “L” shape with a restaurant, with a beautiful crystal chandelier lighted dining room. Silver, linen table cloths and crystal was used as table settings. No man was allowed to enter the dining room in shirt sleeves but the manager kept a supply of coats on hand to loan. An open balcony was extended along the front of the building and a covered screened porch stretched across the back. The grounds were beautifully landscaped with fountains and flowers. On the east side was a cactus garden. A brick walkway lined the front of the building. Along with the luxurious hotel, and restaurant was a newsstand, curio shop, barber shop and depot. It was billed as the best Harvey House west of Chicago.

The Escalante had all the opulence and conveniences of a first class hotel in an eastern city including telephone, hot and cold running water, electric lights, baths and steam heat.

Humorist Will Rogers once remarked “Fred Harvey supplied the West in food and wives.”

It wasn’t just the excellent food that attracted people to his restaurants. Harvey hired a wholesome group of young, attractive, intelligent, women between the ages of 18 and 30 to leave their eastern homes and come west to work as Harvey Girls. For a young woman hoping to escape the hometown doldrums or one with visions of romance and marriage, the job was a dream come true.

Harvey paid good wages, seventeen dollars a month and offered free room and board. They had to be in bed at 10:30 on weekdays and 11:30 on Saturday. The dorms had house mothers to look after the ladies and keep the railroaders and cowboys from trying to sneak in after hours. The women signed a one-year contract promising not to get married until the contract was up but no sooner had she stepped down from the train and the marriage proposals came rolling in. The pretty ones took about a day, while the ugly ones took three days at most.

A Harvey Girl could usually have her pick of the most prosperous gentlemen in town. Harvey never held them to the non-marriage clause, in fact, like a proud father, he’d even throw a wedding party in her honor. The turnover of help was never a problem as there was always a long waiting list of applicants anxious to go west and work as a Harvey Girl. It was said Harvey tried to hire plain-looking girls because they were more likely to fulfill their contracts. Also according to one manager, “the plain ones seemed to get in less trouble.

During its heyday, from 1907 until the end of WWII the Escalante was considered the most elegant restaurant hotel in Arizona. It was a familiar landmark since 1907, competition from roadside ventures along Route 66 caused it to close down it hotel operations in 1951. Two years later the restaurant closed. Despite local resident’s efforts to save it, the stately Escalante was demolished in 1968.