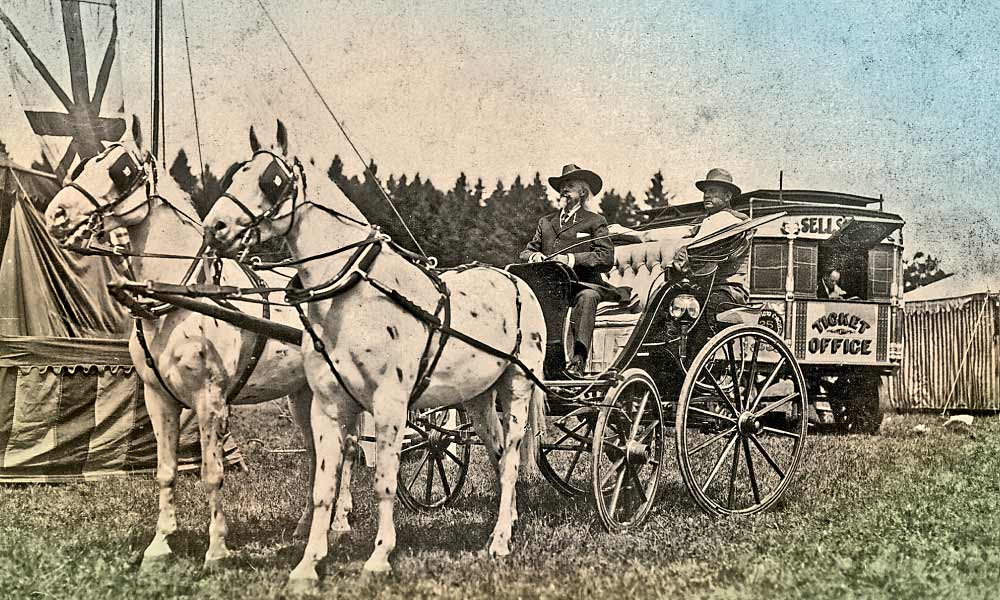

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s showmanship was virtually unchallenged throughout his lifetime, yet he did not possess a strong business acumen. At the end of his 1912 season with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East, Cody realized that profits from his Arizona mine were not enough to finance his retirement. Gordon “Pawnee Bill” Lillie had advanced Cody thousands of dollars for his share in their show business endeavor––often called the “Two Bills Show.” But in 1913, Lillie asked Cody to come up with half of $40,000––enough to winter the show’s animals and finance the next season.

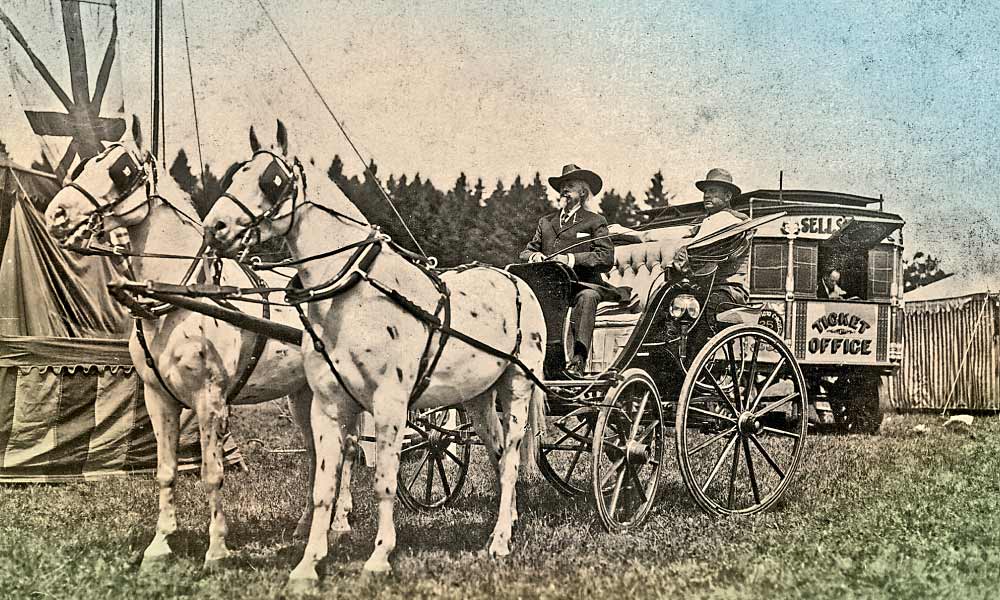

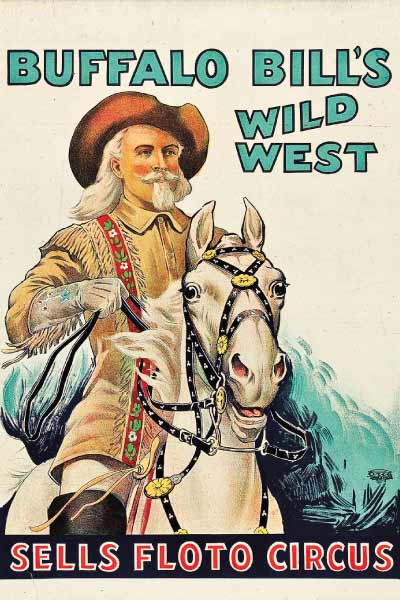

By chance or by design, Harry Heye Tammen, an owner of The Denver Post and a rival circus, met with Cody while the latter was in Denver, Colorado, in January 1913, trying to work up the nerve to ask his sister for money. Tammen seemed to be the answer to Cody’s prayers, because he offered him a loan of $20,000 at six percent interest, to be repaid at the end of six months. On February 5, Tammen’s newspaper publicized the deal he struck with the showman: “Colonel W.F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) put his name to a contract with the proprietors of the Sells–Floto Circus, the gist of which is that these two big shows consolidate for the season of 1914 and thereafter.”

Tammen had taken advantage of the aging Cody’s declining health and financial difficulties. Tammen and partner Frederick Gilmer Bonfils roped Cody into a scheme to effectively steal the Two Bills Show and merge it with their Sells-Floto Circus in order to knock their Ringling Brothers rivals out of the marketplace.

Tammen, who had made his first fortune in the curio business, and Bonfils, who had made his first fortune promoting fake lotteries, performed no task without an ulterior motive. The pair had purchased the failing Denver Evening Standard in 1895 and changed the title to The Denver Post. They founded an empire rooted in Yellow Journalism, building the newspaper into the largest and most powerful of six Denver dailies by the turn of the 20th century.

After Tammen announced that Cody would join Sells–Floto, Lillie called his partner to task. Cody reassured Lillie: “Pay no attention to press reports,” he telegraphed, “I have done nothing that will interfere with our show.”

Lillie was convinced that Cody had double-crossed him and intended to leave at the end of the season.

As for Cody, he likely thought he would be able to pay Tammen back. He was wrong. For 100 successive exhibitions, the Two Bills Show lost money. The year 1913 saw flooding; plus, poor scheduling put the show into freezing rains in a South impoverished by cheap cotton and not turning out in droves to buy tickets. But Lillie and Cody’s biggest blunder was scheduling their show to appear in Denver.

When the Two Bills Show opened for business at Union Park on July 21, deputies led by Sheriff Frank Tammen––Harry’s brother––showed Lillie a writ of attachment for the show. They collected the previous day’s ticket receipts on behalf of the United States Lithographing & Printing Company, which had allegedly provided the circus with $66,000 worth of printed bills, advertisements and signs. Of course, Tammen’s friend owned this company and took direction from him.

“The attorney for the Chicago concern agreed to allow the show to continue upon payment of $25,000, but William Cody would not accept the proposal,” reported The New York Times––most certainly because neither Cody nor Lillie had that money to give.

The circus’s elephants, tigers, horses and dogs were fed at Union Park, while lawmen seized the non-living assets and guarded them in Overland Park. “I haven’t the slightest idea when we will get on the road again, if we ever do,” Lillie told a local paper on July 22. “I am doing my best to settle matters. I mean to stick with my employees, and am doing all I can do to see they do not suffer.”

But suffer they did, because many were stranded as they were unable to pay for rail service home. The “freaks” of the program––the “fat woman,” the “armless wonder,” the “bearded lady”––tried to perform on their own, on the streets of Denver, but the mayor would not give them licenses for the main streets––thus they could not make enough money to pay for hotels or food.

A few months earlier, Lillie had taken the precaution of incorporating the show in New Jersey. He thought that would make him not liable for Cody’s money troubles. Now, after the lithograph company’s bold seizure, Lillie rushed back East to file bankruptcy. But he was forestalled when attorneys in Denver, Colorado, filed a lien for two creditors claiming that they had not been paid for merchandise and stock feed.

Before Lillie could act, a Denver court allowed the assets to be put up for auction in order to satisfy creditors. Cody sobbed as his iconic white horse Isham was advertised for bidding; friends who felt sorry for Cody bought the horse for him so the pair wouldn’t be parted.

While Cody later called Tammen a crook, at this time, he blamed Lillie for their current woes. He wrote his attorney Clarence Rowley on July 25: “The old show went out of business on the 22d— It nearly broke my heart. And could have been avoided if Lillie had not been like a dog in the manger.”

For his part, Tammen played to Cody’s ego––noting in his newspaper that he had tried every way possible to work out a deal with Lillie, and that he did not hold Cody responsible: “And I want to say finally that nothing would please me or my company more than to see Colonel Cody relieved of his embarrassments and on the road again with the show which he has spent his life in building up.”

Since Cody had burned his bridges with Lillie, he had no choice but to perform for Tammen and Bonfils, whose traveling extravaganza became the “Sells-Floto & Buffalo Bill’s Combined Shows.” Cody toured with the show for two seasons, exhausted most of the time. Tammen had promised him large percentages of ticket sales above $3,000 per day, but this almost never happened due to bad weather and accidents. Cody tried to leave, but Tammen held him to the remainder of his debt.

Cody wrote a friend about his anger and anxiety: “Of course I have got to see Tammen and I have got evidence enough to land him in the Penitentiary…I am in such bad luck that [I] might fall down––I am very tired nervous and discouraged.”

At the close of the 1915 season, Cody figured he was due some $18,000 in profit from the venture, although he did not expect to collect from Tammen. The two were glad to be rid of each other. Yet Tammen could not resist one final extortion attempt: when Cody announced he was going to revive his Buffalo Bill’s Wild West circus, the businessman warned that he owned the name, and he would charge Cody $5,000 every time he used it.

In early 1916, the Supreme Court announced it would not reverse a lower court ruling that the Denver businessmen had conspired to “steal a circus in broad daylight.” When Tammen and Bonfils did not pay Lillie’s trust the $45,000 they owed, the court ordered their accounts examined and found out that these millionaires had not paid corporate or personal income taxes since 1911. Their rival Rocky Mountain News and other newspapers seized upon this information, and the headlines helped to hand the men’s political nemesis another term as Denver mayor.

Still, the businessmen’s stranglehold on Denver administrators was so tight that when the circus was once again put up for auction, in December 1916, they were able to purchase it through an intermediary for pennies on the dollar.

Cody found work in other Old West shows, but he never again owned his own. Years after Cody’s death on January 10, 1917, Lillie reminisced about the end of their show: “Time smooths everything. Buffalo Bill died my friend. He was just an irresponsible boy. As for Bonfils and Tammen, well, you can’t say very many good things for men who hounded you and broke you just for the fun of it.”

Strangely, though, one of those men, Tammen, had paid for Cody’s elaborate funeral in Denver.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions, November 2010 –

Julia Bricklin is a frequent contributor to history publications and a member of Western Writers of America. She is the author of a forthcoming book from University of Oklahoma Press about sharpshooter Lillian Frances Smith.