With the sesquicentennial of the Civil War quietly coming to a conclusion in 2015, a reconsideration of the Confederate presidency of Jefferson Davis and his leadership as commander-in-chief of the Confederacy gives pause, considering the terrible toll the war exacted on the United States.

With the sesquicentennial of the Civil War quietly coming to a conclusion in 2015, a reconsideration of the Confederate presidency of Jefferson Davis and his leadership as commander-in-chief of the Confederacy gives pause, considering the terrible toll the war exacted on the United States.

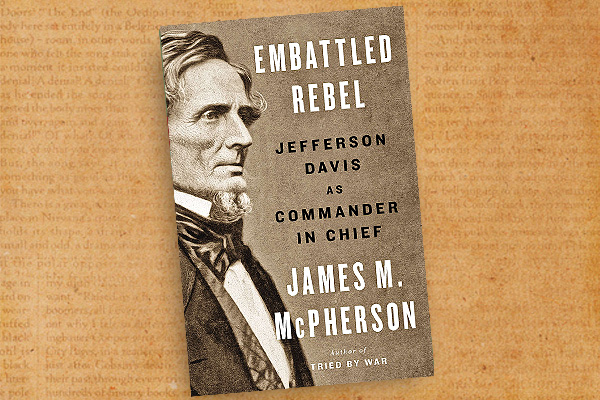

Award-winning biographer and Civil War historian James M. McPherson’s Embattled Rebel: Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief (The Penguin Press, $32.95) is a thoughtful, focused, biography of the controversial Confederate leader. Like his earlier biography of Davis’s nemesis, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief, McPherson does not expound beyond the boundaries of Davis’s role as military leader of the Confederacy, albeit the complexity and magnitude of the Confederate commander’s life would lead many other biographers to author a much broader examination of Davis’s influence on American history. McPherson concludes that “no other chief executive in American history exercised such hands-on influence in the shaping of military strategy.”

As a Lincoln scholar, McPherson, who admits in his introduction “his sympathies lie with the Union side of the Civil War,” attempts with a great deal of academic caution, to embrace the “hero” of his biography. This approach seems to be one of the most difficult assignments the George Davis ’86 emeritus history professor from Princeton University has ever attempted. Nonetheless, McPherson admits, “I found myself becoming less inimical toward Davis than I had expected when I began the project.” The Pulitzer Prize-winning author successfully overcame his biases and his work demonstrates that Davis’s fortitude to overcome personal challenges, health issues and political rivals was equal to his rival, Lincoln. The author’s cautiousness in embracing his hero’s (Lincoln) sworn enemy does not lead to broader praise or contextual importance to American history, McPherson does conclude that Davis was a near-match for the savior of our nation: Davis shaped and articulated the principal policy of the Confederacy with clarity and force: the quest for independent nationhood.”

Fortunately, McPherson’s The Embattled Rebel is not the final biography or synthesis on the Civil War scheduled for publication during the sesquicentennial. Readers seeking greater context to Davis’s complex life and career as soldier, citizen and politician prior to 1861, hopefully will find it through McPherson or Emory M. Thomas providing a broader understanding of the Confederate commander in chief’s influence on Manifest Destiny, the antebellum political battle over slavery, states’ rights, national economics, international trade, and the development of the West, including the transcontinental railroad. In the interim, McPherson’s penultimate conclusion on Jefferson Davis’s role as commander in chief, and strategic partner with Lee contrasted with Lincoln and Grant, is simple and at the foundation of 150 years of debate: “the salient truth about the American Civil War is not that the Confederacy lost but that the Union won.”

—Stuart Rosebrook