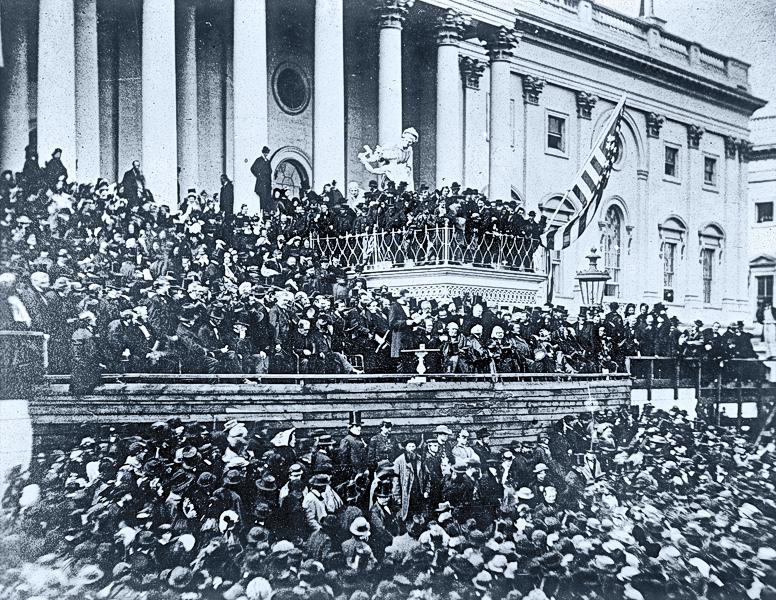

At first, I think I’ve made a wrong turn somewhere, because this doesn’t feel like the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. It’s more like…Disneyland.

At first, I think I’ve made a wrong turn somewhere, because this doesn’t feel like the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. It’s more like…Disneyland.

Don’t get me wrong. Springfield, Illinois, Honest Abe’s home and final resting place, should brag about its state-of-the-art museum that opened in 2005. Exhibits give visitors a you-are-there feeling. Even the late journalist Tim Russert covers the 1860 presidential campaign with 21st-century technology. That should make history relevant for kids.

It’s utterly fascinating.

So is Lincoln.

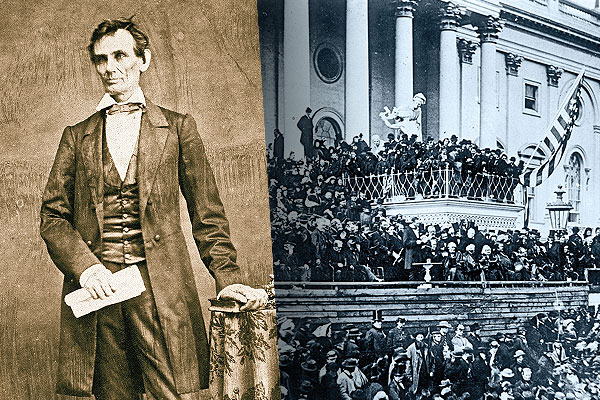

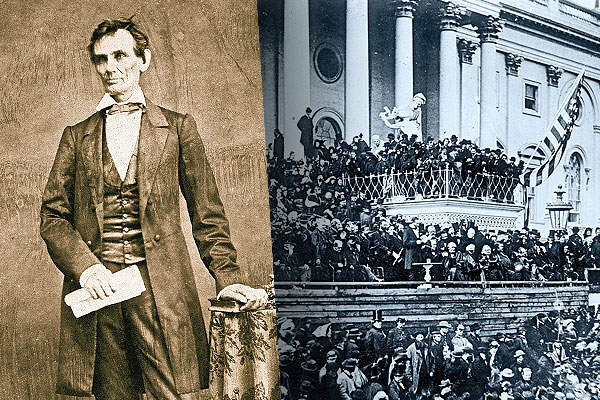

Typically, Lincoln brings to mind the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Gettysburg Address and Ford’s Theatre.

Yet on the 150th anniversary of his death, let’s seek out Lincoln’s influence and legacy pertaining to the American West.

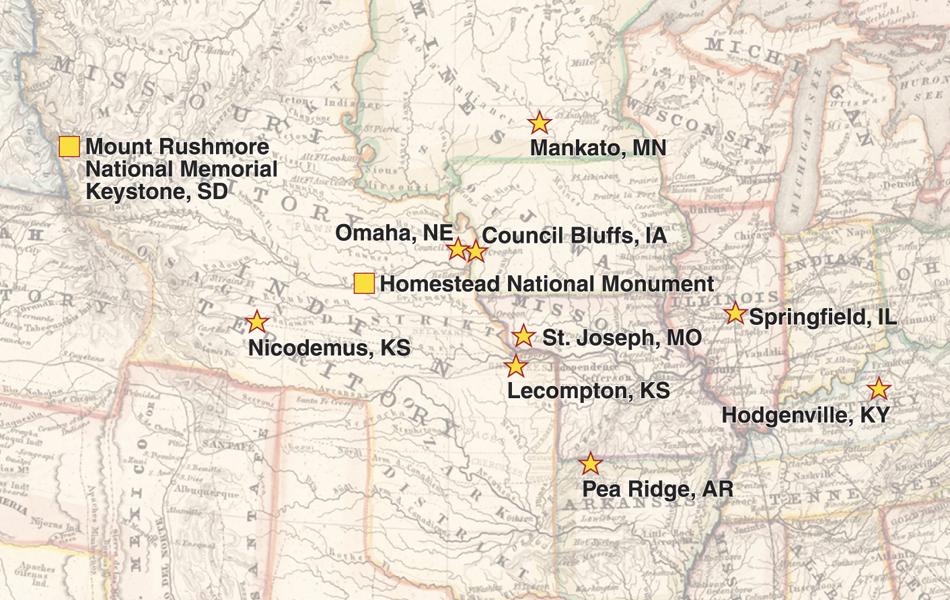

Springfield—also home of Lincoln’s Tomb—definitely tops the list for Abe fans. But your travels should also include:

1. Hodgenville, Kentucky

Lincoln was born in a single-room farm cabin here on Sunday, February 12, 1809. Andrew Jackson might be the first “Western” president, but Lincoln did a lot for the West, and Kentucky was the frontier and helped shape the man (his parents belonged to an anti-slavery Baptist church).

Today, an 1800s log cabin inside the Memorial Building stands on the birthplace site. The building was dedicated by President William Taft in 1911. While the cabin is not Abe’s actual home, that doesn’t matter; the National Park Service also maintains Lincoln’s Boyhood Home about 10 miles away. In 1811, a land title dispute sent the Lincolns from Sinking Spring to Knob Creek, where the family lived for the next five years before moving to Indiana.

No, the Lincolns did not make Knob Creek bourbon, but today it’s a Jim Beam product and visitors can tour the Jim Beam American Stillhouse in nearby Clermont.

2. Pea Ridge, Arkansas

Of course, Lincoln is most identified with the Civil War, and while most battles were fought in the East, the war reached the West.

Perhaps the most important battle west of the Mississippi took place at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 7-8, 1862.

Roughly 26,000 soldiers battled here, and things got Western. Wild Bill Hickok is said to have fought for the Union while some of Confederate Gen. Albert Pike’s Cherokee Mounted Rifles scalped and mutilated Union soldiers.

The Union victory kept Missouri in Union control.

Today, this 4,300-acre National Military Park honors those who fought on both sides. For the true Western experience, there’s even a nine-mile horse trail.

3. St. Joseph, Missouri

Most people know about the Pony Express, whose riders delivered some 34,763 letters and rode roughly 616,000 miles during its 18 months of existence.

The fastest delivery from St. Joe to Sacramento, California, took seven days, 17 hours; the riders carried the story of Lincoln’s inaugural address. Another series of rides—eight days, 14 hours—informed California that Fort Sumter, South Carolina, had been shelled.

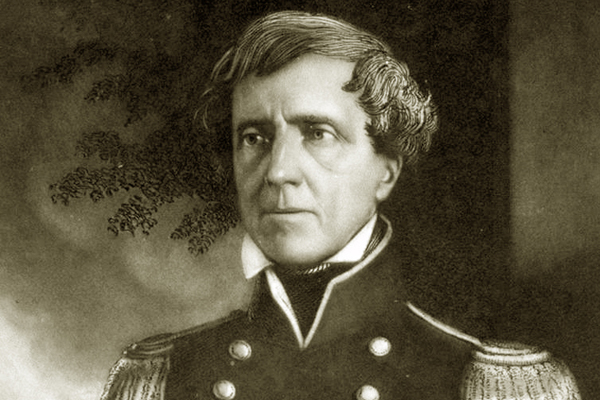

Yet another Pony Express story claims that Sacramento Bee founder James McClatchy uncovered evidence that General Albert Sidney Johnston, commanding the Department of the Pacific, planned on turning army stores over to the South. McClatchy sent a letter to Senator E.D. Baker, delivered by the Pony Express (at least to St. Joe), and when word reached Lincoln, he ordered Gen. Edwin Sumner to California to relieve Johnston. I’m not sure if it’s true, but it makes a good tale. Johnston resigned in March 1861 and was killed at Shiloh in April 1862.

Even if you don’t go for spy-thriller stuff, the Pony Express National Museum in St. Joseph, with its Pikes Peak Stables and great artifacts, is fun to visit.

4. Lecompton, Kansas

No, Lincoln didn’t speak here—he did in Elwood, Kansas, just across the river from St. Joe, in 1859—but Lecompton might have been the key to Lincoln’s political life.

In 1855, Lecompton became Kansas’s territorial capital, and here the legislature drafted a constitution that would admit Kansas as a slave state. Slave state? When most Kansas settlers abhorred slavery? That happened because pro-slavery Missourians crossed the border to cast ballots (another reason it’s not safe to wear University of Missouri T-shirts in this state).

In Washington, the Senate passed the constitution, but the House eventually rejected it in February 1858. President James Buchanan wanted the constitution to pass; Senator Stephen Douglas was adamantly against it. In the end, the Democrat party split into bickering factions, which allowed Lincoln to win the presidential election with 39 percent of the popular vote. Lincoln wouldn’t have become president without the Lecompton constitution.

At least, that’s what they say here, where history is preserved at the Territorial Capital Museum, Constitution Hall and 1854-61 Democratic Party headquarters.

5. Nicodemus, Kansas

Sure, it’s post-Lincoln, but there would be no Nicodemus—or other black settlements in the West—if not for our 16th president.

Former slaves from Kentucky decided to head for the promised land of Kansas, forming Nicodemus Town Company on April 18, 1877. A 160-acre townsite plat was filed in June. By the end of July, some 30 settlers had arrived. Hundreds more would follow before hard winters and the lack of a railroad doomed Nicodemus, which began fading away by the late 1880s.

Faded, but never completely abandoned. Since 1996, Nicodemus National Historic Site has preserved one of the oldest and the only remaining black settlements west of the Mississippi. Five buildings keep this town’s legacy alive.

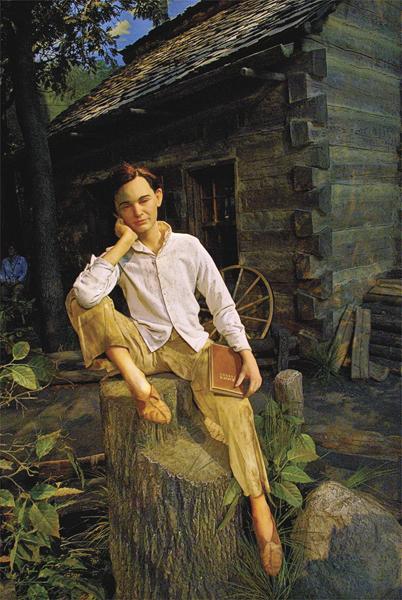

6. Homestead National Monument, Nebraska

Lincoln absolutely helped the Westward movement with the Homestead Act of 1862, saying the government needed “to elevate the condition of men, to lift artificial burdens from all shoulders, and to give everyone an unfettered start and a fair chance in the race of life.”

The act granted 160 acres of free land to claimants.

Easy land? Not hardly. You had to improve the claim to get your deed. Plowing 10 acres—required for the homestead—meant walking at least 100 miles.

The first person to file claim was Daniel Freeman, who filed in Brownville, Nebraska, at 12:10 a.m. (government hours were not like they are now) January 1, 1863.

It’s Freeman’s farm that the National Park Service preserves roughly four miles west of Beatrice, but the park’s not just about Freeman. It celebrates those 1.6 million homesteaders who transferred 270 million acres from public land to private hands.

7. Council Bluffs, Iowa/Omaha, Nebraska

Another part of what might be considered Lincoln’s New Deal for the West was the Pacific Railway Act, which became law on July 1, 1862.

This law paved the way for the transcontinental railroad, which linked East and West. Abe didn’t live to see completion of the railroad at Promontory Point, Utah, in 1869.

To celebrate Lincoln and the rails, check out the Union Pacific Railroad Museum in Council Bluffs, where the Lincoln Collection Exhibit celebrates all things Abe. And cross over into Omaha’s Historic Old Market to see the Durham Museum, housed in Union Station.

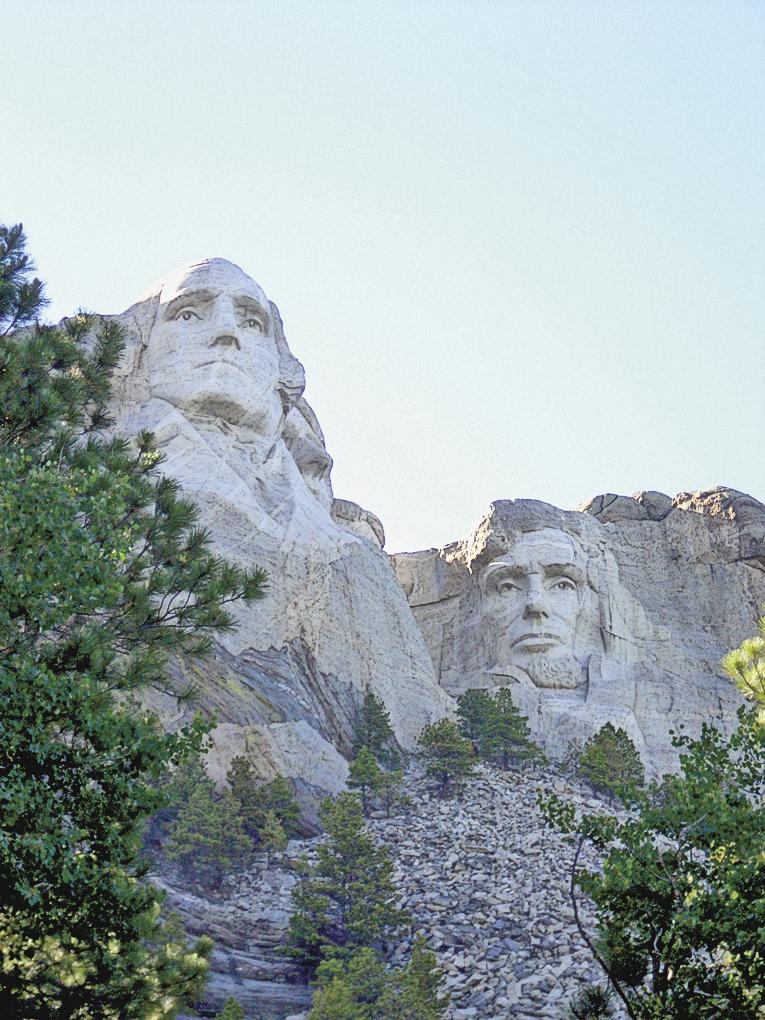

8. Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota

Three million people can’t be wrong, and that’s how many people visit this towering monument near Keystone in the Black Hills.

Lincoln shares billing with George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt.

George did the founding, Tom did the expanding, Teddy did the preserving and Abe did the unifying.

Gutzon Borglum did the carving. Well, a lot of it, anyway.

Construction began around 1927, and the presidents’ faces were completed between 1934 and 1939. The original plan was to feature the presidents all the way down to their waists, but Borglum died in March 1941, which pretty much ended the carving and led to the dedication of Mount Rushmore on October 31, 1941.

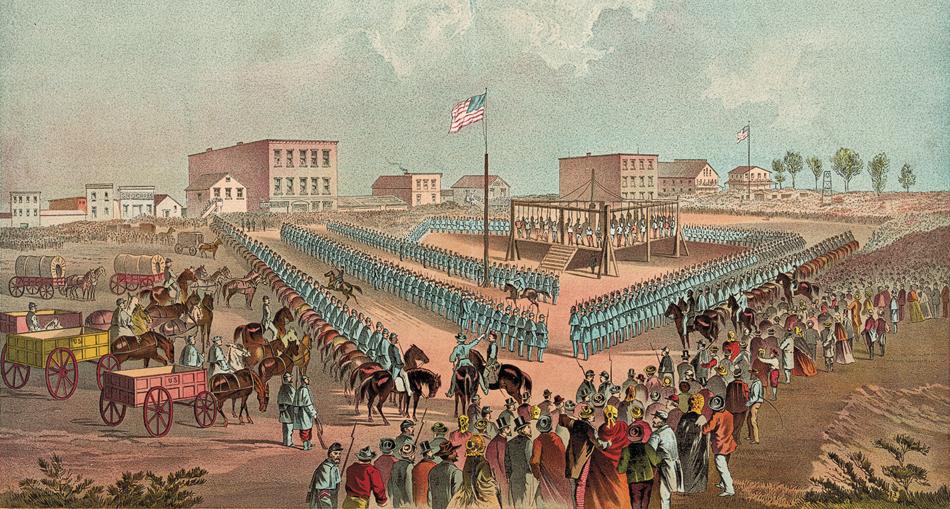

9. Mankato, Minnesota

Not everything Abe did was pleasant. A lot of Indians west of the Mississippi likely aren’t celebrating the passage of the Homestead or Pacific Railway acts. And they certainly don’t like what happened in this southern Minnesota city in 1863.

Lincoln, whose grandfather had been killed by Indians, met with several Indians during his terms, but “Lincoln’s call to ‘bind up the nation’s wounds’ was never applied to Native Americans,” historian David A. Nichols writes.

With the Dakota outbreak almost over, military tribunals left more than 300 Dakotas sentenced to death. Lincoln stepped in to review the transcripts and eventually commuted the sentences of hundreds, but not all.

Thirty-eight Indians were hanged here on a single platform on December 26, 1862, in America’s largest mass execution.

More than 150 years later, one Indian website notes: “YOUR GREAT ‘EMANCIPATOR’ WAS A MURDERER PLAIN AND SIMPLE.”

Visitors won’t find much about the hanging at the Blue Earth County Heritage Center, but Reconciliation Park was dedicated in 1997 on the execution site.

It’s not a fun place to visit, which is why maybe we should return to Disneyland—I mean, Springfield, Illinois.

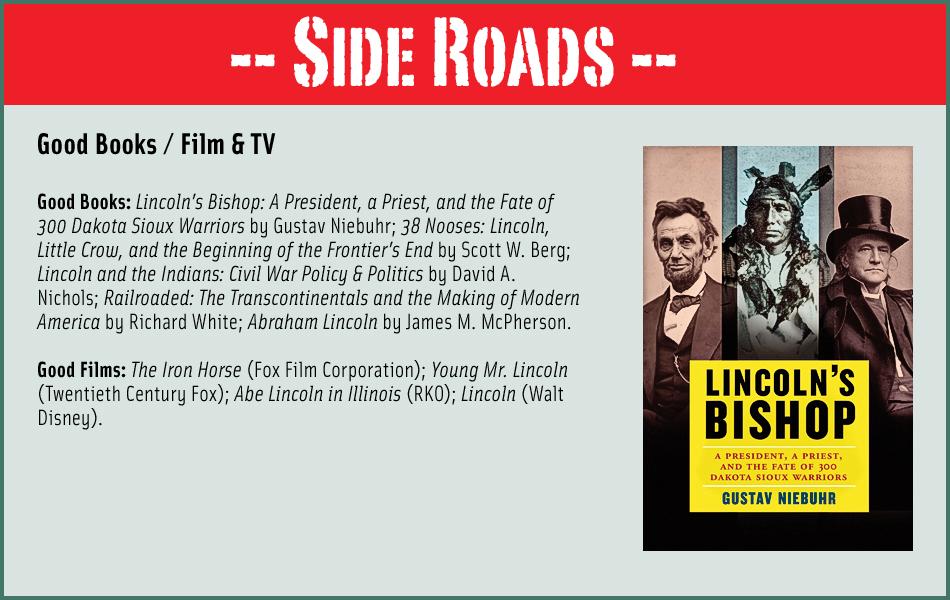

Johnny D. Boggs thinks Raymond Massey is a better Abe in Abe Lincoln in Illinois than Henry Fonda is in Young Mr. Lincoln—but Hank’s still his favorite Wyatt Earp.

Photo Gallery

– Photos Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Johnny D. Boggs –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Photos Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Johnny D. Boggs –

– Stuart Rosebrook –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –