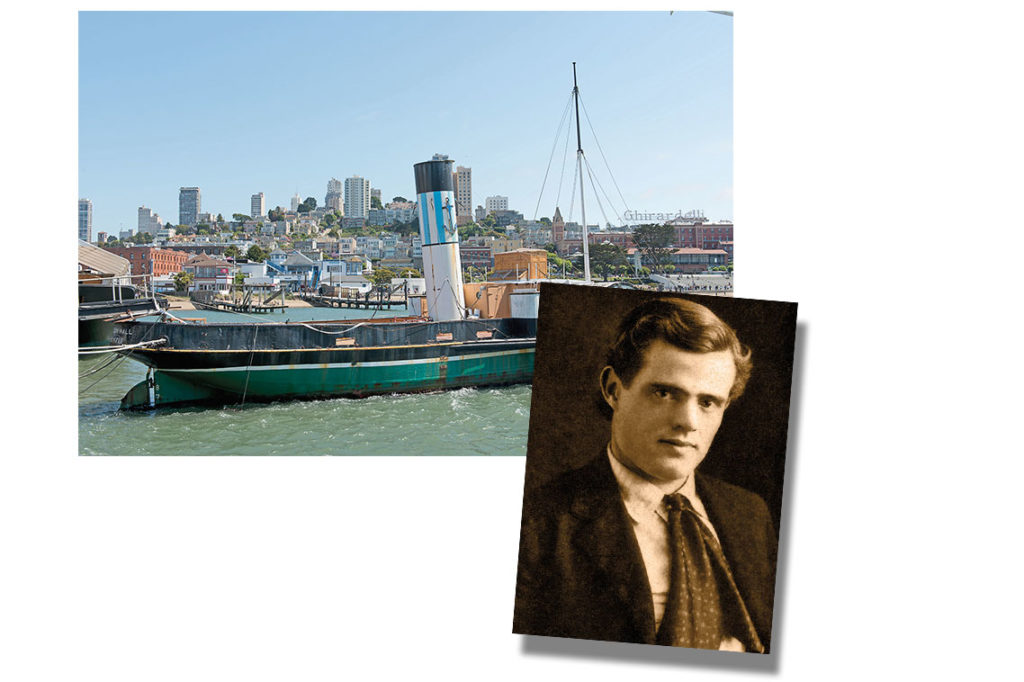

– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

The 1898 Klondike gold rush and the later rush to Nome, Alaska, have long been legendary. Who doesn’t remember Johnny Horton, Sam McGee and White Fang?

Why, Jack London’s The Call of the Wild remains in print and has been filmed countless times…with Clark Gable, Charlton Heston, Rutger Hauer and others acting alongside a dog named Buck. Hollywood’s still at it, with Harrison Ford starring in director Chris Sanders’s offering this year from 20th Century-Fox. (Pssst…Charles Chaplin’s The Gold Rush is better than any of the London adaptations.)

The discovery of gold in northwestern Canada sent an estimated 100,000 people north from 1896 to 1899—though only some 30,000 made it all the way to the Yukon’s Klondike, and 4,000 or so of those actually found pay dirt. You couldn’t blame Americans for trying, what with the country mired in depression since the Panic of 1893, and newspapers blasting news of riches.

“The tide,” Tappan Adney wrote in The Klondike Stampede (1900), “was too great to turn.”

But those prospectors had to get to Alaska and the Yukon first, and those escapades are practically as intriguing as rugged hikes up the Chilkoot Trail; crooked Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith’s shenanigans in Skagway, Alaska; and harrowing raft rides through Miles Canyon.

The first year of the rush saw 20,000 to 30,000 wannabe millionaires heading north. “A miner intending to go to the Klondike has the alternative of buying on the American side and paying duty, or of paying here,” Adney learned in Victoria, British Columbia.

North from San Francisco

Some took the Canadian route, but most set out from a U.S. port.

“All the [Pacific] coastal ports…were locked in an intense struggle for the lion’s share of the booty, each city screaming that it was the only possible outfitting port for the Klondike,” Pierre Berton wrote in The Klondike Fever: The Life and Death of the Last Great Gold Rush (1958).

The San Francisco Call reported hopefully on December 13, 1897: “when the spring rush to the Klondike starts[,] …the principal exodus will be from this city, instead of the more northern ports.”

Gold, of course, was nothing new to San Francisco, and when the San Francisco Historical Society opened its new museum last year, its inaugural exhibit was Gold Fever!, which focuses on earlier California gold strikes. Tony Bennett’s city by the bay is worth exploring for its history (Wells Fargo Museum, The Society of California Pioneers, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park) and clam chowder in a sourdough bowl.

– True West Archives –

Bring “good health and a good brave heart,” Joaquin Miller told potential prospectors in the San Francisco Examiner on March 10, 1898. “Bring faith and hope and charity; charity that you may not quarrel with the frailties of your fellow-miners; but first of all is the heart—the heart of a lion. After good health and a good heart, bring an even, honest, good temper. Don’t try to come here bilious.”

Newspapers lauded their homes’ triumphs and blasted the competition. “Up and down the coast the arguments reverberated,” Berton wrote. “Seattle papers published bitter editorials attacking the claims of Tacoma and San Francisco, and the rival cities retorted in kind.”

Across San Francisco Bay, Oakland (Peralta Hacienda Historical Park, Oakland Museum of California) saw its share of problems attributed to gold fever. “J.R. Fowels,” the Oakland Tribune reported February 21, 1898, “the crack first-baseman and heavy-weight batter for the Elmhurst ball tossers, leaves for Seattle Thursday evening. He will probably go into the Klondike district.”

Say it ain’t so, Joe.

But one Oakland resident made a name for himself in the Klondike. Although he spent a lot of time along the waterfront (now Jack London Square), Jack London developed a knack for writing. In July 1897, the 21-year-old took off for the Klondike, where he came away with scurvy and fodder for stories, including “To Build a Fire.” His ranch home in Glen Ellen is a must.

Stop in Sacramento (California State Railroad Museum, Sacramento History Museum, Sutter’s Fort and Leland Stanford Mansion state historic parks) for a look at California/gold history. Then make that long drive north—stopping for more California gold history in French Gulch, west of Redding—to Portland, Oregon (Oregon Historical Society Museum, Oregon History Museum).

Back from Nome in 1902, former Portland police captain John L. Sperry noted this about most Klondikers: “About 75 per cent don’t know gold when they see it, except in the shape of a $20 gold piece.”

Portland to Seattle

Portland, already boasting a population of roughly 60,000, advertised its virtues for gold-seekers with pamphlets, maps and promotional publications. Calling for fellow entrepreneurs to kick in with advertising dollars to get the gold-seekers’ business, W.A. Mears warned: “You will have yourself to thank if you see Seattle go ahead with a bound and distance this city in wealth and population.”

Traveling north, you should detour to Mount Rainier National Park, which subbed for the Klondike in the 1928 silent film The Trail of ’98, before reaching another port that vied for Klondike cash.

– Historic Photo of Seattle Courtesy Library of Congress –

Tacoma, Washington (Tacoma Art Museum, Washington State History Museum) reaped rewards from the gold rush. But Seattle won the Klondike war. In fact, Frank Goodwin developed Seattle’s famous Public Market—after he returned from the Klondike with his share of the wealth.

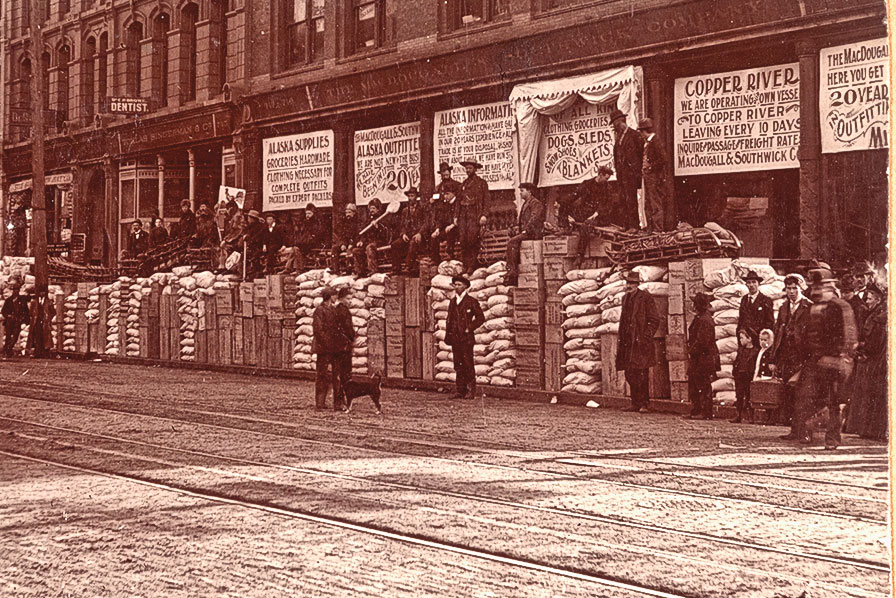

Seattle (Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Log House Museum, Museum of Pop Culture) had railroads and was the closest U.S. port to the goldfields. It had survived an 1889 fire that swept through the commercial district and was the first continental American city to get news of the gold strike when the steamship Portland docked in Seattle on July 17, 1897, bringing 68 prospectors who had boarded in St. Michael, Alaska. Newspapers might have underplayed the story at first, but Seattle soon became the main jumping-off point.

As Berton wrote: “…in 1899 alone, twelve hundred new houses mushroomed up in the city, and the merchants, who before the rush had sold goods worth an annual three hundred thousand, now found that their direct interest in outfitting amounted to ten million.”

One visitor heard so much about Seattle from Klondikers that instead of returning home to London, he visited Seattle late in 1897. “I must say,” he told The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “you have a very lively city here.”

Johnny D. Boggs is the Western Writers of America’s 2020 Owen Wister Award recipient for Lifetime Contributions to Western Literature.