By William CX Hancock with Mrs. Edgar Thomas Neal

The young Ranger rode out from Rio Grande City through the prickly pear flats where Pancho Morales was rendezvousing with his woman. He tied his horse some distance from the shack, then stealthily closed in on foot. He kicked the back door open and, in spite of his 225-pound frame, stepped inside with the speed of a panther, a Colt gripped in his right hand.

“Raise your hands, Pancho! This is Edgar Neal. Got a warrant for your arrest.”

Pancho and the woman were seated at a rude table, drinking tequila. Fortunately, the light was provided by a kerosene wall-lamp out of the fugitive’s reach. His back was toward Neal. With half-raised hands, he got slowly to his feet and faced about.

“Amigo mio,” he said, his eyes venomous slits, “Pancho very sorry we meet like this.”

“Me, too, Pancho. Powerful sorry,” said Neal with moving sincerity. In his youth, he had clerked in a grocery store where the Mexican was a delivery boy. Later, the two had punched cattle together for various South Texas outfits. But now, in 1896, Morales was high on the Texas Rangers’ wanted list—a rustler, he had killed several men and eventually murdered a Texas lawman. Edgar Neal had been ordered to bring him in alive.

“Hand over your pistol slow and easy with your fingertips and gun butt first.” He was speaking so kindly that he might have been requesting Pancho to pass the tortillas.

Morales did not comply. “Señor, it is better that Pancho die here than be hanged by gringos.” He was very tense and obviously getting set to attempt a draw. Neal’s non-killing record was hanging by the merest thread.

“I hate to do this to anybody,” said Neal in his most sympathetic manner. “You can imagine, Pancho, how much I hate to do it to an old friend.”

Pancho reflected upon this for a moment while the patient Neal waited. The Mexican began to relax and presently a faint smile of resignation crossed his dark features. Slowly he handed over his pistol as directed and extended his hands, palms together, for the handcuffs.

This type of triumph had been repeated in various forms until this soft-spoken, non-

smoking, non-drinking , non-swearing young Ranger was heralded throughout the force.

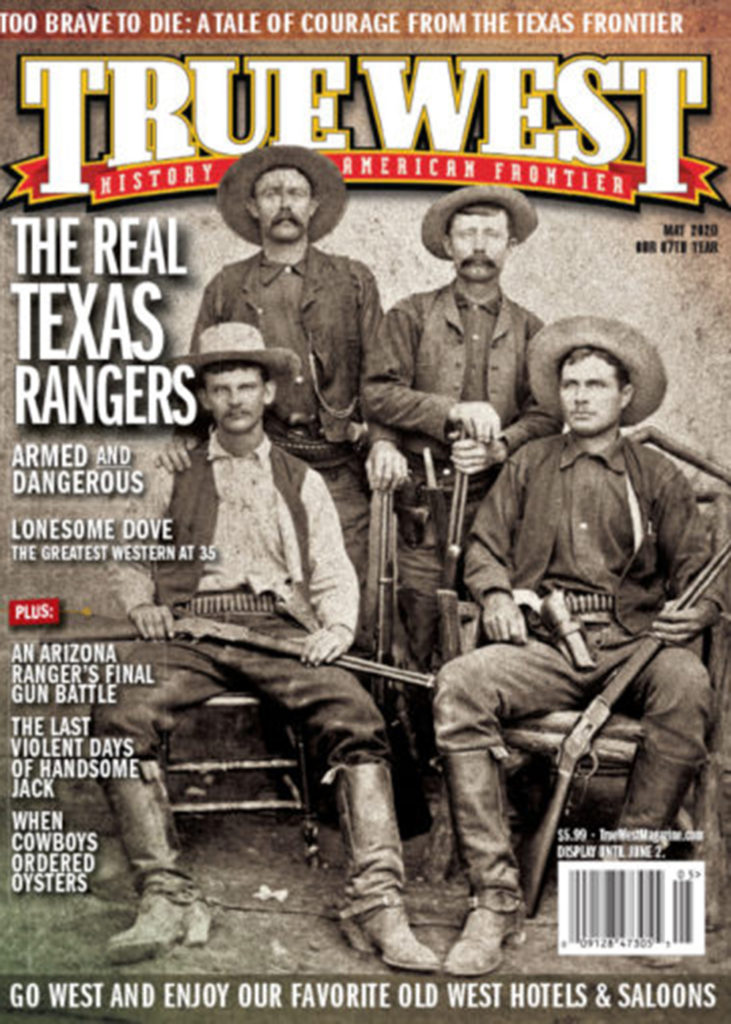

Twenty years a Texas Ranger during some of the most turbulent times once rough-and-ready Texas has known, and 16 years sheriff of faction-ridden, strife-torn, pistol-haunted San Saba County, the fabulous Captain Edgar Thomas Neal never killed a man.

As some of his still-living cronies often remark: “Just because he never killed anybody; don’t think for a moment that there was ever the slightest doubt in anyone’s mind that he would kill if necessary. He just didn’t let it get necessary.”

The six-foot, two-inch lawman was born in 1870 in Wilson County, birthplace of several famous Texas Rangers, including the nationally-known Captain Frank Hamer. Both attended Rabbit Hill School, and it is an interesting coincidence that Hamer was to send more outlaws spinning into the dust with his blazing Colts than any other lawman in the history of the West, while Neal was never to kill anybody. In later years, it was a standing joke between these two peerless manhunters that they developed their abilities in running down lawbreakers by chasing the countless jackrabbits which infested old Rabbit Hill.

In the heart of Texas lies the beautiful ranching county of San Saba—a region so blessed by nature that the Indian name for it means “Happy Hunting Ground.” Before the Civil War, the people were dedicated to mutual helpfulness and common defense against the Comanche Indians. But post-war days witnessed the development of rampant lawlessness in which honest citizens came to despair of ever receiving justice at the hands of carpetbagger government and rigged courts. Inevitably they took the administration of justice into their own hands, and there came into being the notorious “Mob of San Saba.”

In the earlier stages of its operation, Mob membership included many of the best people. Known rustlers were hanged, land-claim jumpers despoiled, and undesirables in general given the bums’ rush. But true to the history of mob law, leadership eventually gravitated to selfish and power-hungry individuals.

Came the time when the county found itself gripped in a reign of terror. Resultant homicides had approached half a hundred when a woman, whose father was a member of the Mob, had them murder her prominent husband to free her for further romance.

An “anti-mob” was formed and informed Governor C. A. Culberson of conditions in the county, petitioning him for Rangers to help clean up the mess. He ordered his adjutant general to “send four of your bravest Rangers to San Saba.”

Edgar Neal was one of the four Rangers selected. He and Allen Maddox of Company E from Alice rendezvoused at Goldthwaite with Sergeant John L. Sullivan (later a famous captain) and Dudley Barker of Company B from Amarillo—all noted gunslingers. The group quietly assembled a wagonload of supplies and camp gear and set a course southwestward for San Saba County, where they went into camp August 13, 1896, near Regency on the Colorado River—scene of the latest killing in which rancher Bill James had been bushwhacked while peaceably hauling water from the river. The famous old Indian fighter “Uncle Buck” Chamberlain was chosen camp cook and deputy.

The attitude of local authorities alleged to have been Mob-connected was most hostile toward the Rangers. The rank-and-file mobsters were so openly threatening that Neal’s group had to maintain security measures at night around their camp. However, they entered upon long months of patient investigation for purposes of gathering sufficient evidence to seek indictments. Neal’s phenomenal ability to inspire trust in people was never more valuable than now as San Sabans began to disclose needed information to him. The lawman, a solitary horseman riding leisurely down lonely trails, became a common sight in San Saba Land—a frightened county, run by a 1,000-man Mob, most of whose members secretly regretted their association but dared not sever the tie for fear of the sinister leader, Bill Ogle.

By the middle of May 1897, the four Rangers were ready to present their evidence to a grand jury. With the concurrence of the adjutant general, they had promised the potential witnesses adequate protection in the form of additional Rangers who, unknown to the Mob, were enroute to San Saba. On Saturday morning preceding the Monday on which the grand jury was to be convened, the Mob began to gather in San Saba with the announced purpose of running the Rangers out of town. Sergeant Sullivan and Allen Maddox, each armed with two Colts, their horses tethered nearby with Winchesters tied on the saddles, posted themselves at the northeast corner of the courthouse square. Neal and Barker, similarly armed, took stations at the southwest corner.

Knots of mask-wearing mobsters had their heads together here and there about the square in deep conversation. Whiskey bottles passed back and forth. By apparent arrangement, the knots began to fuse into two large groups, one edging toward Sullivan and Maddox, the other toward Neal and Barker. The latter group made the first move. As they approached, the two Rangers eased behind their horses for protection as well as quick access to their rifles. The group leader faced Barker, being unable to rib himself into sufficient fury against the kindly Neal. “We’re giving you sons-of-b—— fifteen minutes to get out of town,” he said. “Fifteen minutes! You hear? Now git!”

The man reached for his pistol. …