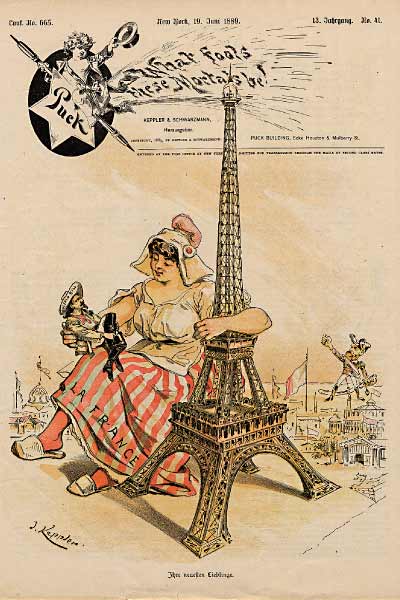

Paris was a city Buffalo Bill’s Wild West hoped to conquer. Cody’s show proved a sensation. Parisians flocked to Neuilly to see the Wild West extravaganza over the next several months. Stetson cowboy hats became the rage, and the “Buffalo Bill Galop” was the best-selling sheet music in town. Excitement about Buffalo Bill’s Wild West swept through Paris like a fever. By the end of the summer, the newspapers likened Cody’s capture of Paris to the taking of the Bastille.

One could blame the success on journalist and author Mark Twain. Twain wrote Cody in 1885, “I have now seen your Wild West show two days in succession, and have enjoyed it thoroughly. It brought back vividly the breezy, wild life of the great plains and the Rocky Mountains and stirred me like a war song.”

Praising the show for being genuine, his letter went on to remark, “It is often said on the other side of the water that none of the exhibitions which we send to England are purely and distinctively American. If you take the Wild West show over there you can remove that reproach.”

Cody, who had already been considering transporting the show to Europe, took this advice to heart. The next year, when he was invited to be part of the American Exhibition at Queen Victoria’s 50th Jubilee celebration in 1887, he jumped at the opportunity.

Journey to Paris

Cody was the right person at the right time, and, as it turned out, at the right place to promote the American West in Europe. Born in Iowa Territory on February 26, 1846, he had grown up in the West, experiencing the strife in Kansas Territory prior to the Civil War. He made his first journey across the Great Plains at age 11. He traveled to what became Colorado Territory in 1859 during the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, delivered mail for Alexander Majors’s firm (although not for the Pony Express route Cody would make famous through his shows), hunted buffalo and scouted for the U.S. Army. He learned one of the most important scouting skills, how to feel comfortable around and communicate with American Indians, who knew more about the Plains than the newcomers. Charismatic and likable, Cody soon became the focus of newspaper articles and dime novels about the American frontier.

In 1872, Cody began appearing on-stage in plays about the West. The plays were successful, but Cody had even greater ambitions. After 10 years touring the country with his acting troupe, he moved outdoors. The arena provided an opportunity to stage re-creations of life in the West with a cast of hundreds and for an audience of thousands. That year, 1883, proved to be pivotal for Cody. With the inception of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Cody took a leap from the small stage to the world stage.

Four years after its creation, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West became a runaway success in London, England, eclipsing every other American offering at the exhibition honoring Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee. Attendees were eager to observe, in person, an America that they had read about in James Fenimore Cooper’s novels, in news dispatches and in dime novels. Cody was the toast of the town, meeting everyone from Queen Victoria herself to author Oscar Wilde. Author Bram Stoker later based one of the characters in his novel Dracula on Cody. James McNeill Whistler vowed to paint Cody’s portrait, although he never did get around to it, as he instead turned his attention to matronly figures. Cody returned to the United States in late 1887, with the sweet taste of European success in his mouth.

The Wild West toured the northeastern U.S. during the 1888 season, but Cody could not shake Europe from his mind. His interest in the European continent had been whetted by a brief vacation there with his daughter during the London sojourn. When the opportunity arose to visit Paris for the 1889 Exposition Universelle, he jumped at it.

Nearly Eclipsing the Exposition

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was not set up within the exposition grounds, which were adjacent to Eiffel’s tower. The extravaganza was situated in Neuilly, just a few kilometers away, and near the Bois de Boulogne, a park popular with Parisians and easily accessible from all parts of the city. Almost immediately, the Wild West became the most popular show in town, nearly eclipsing the exposition itself.

Critics observed of Cody’s first appearance on the American stage that he was no actor, but they also noted his ability to charm the audiences. He was clearly a showman. He brought not only his experiences and a personal flamboyance to the Wild West, but also an innate sense of what audiences wanted. His show did not re-create endless hours on the trail or weeks huddled in a cabin during the winter, but instead distilled out the exciting aspects of Westward Expansion.

The Wild West didn’t just re-create exciting events; it also offered visitors the opportunity to learn about the peoples of the West, who exhibited their skills and cultures. More than 100 American Indians, including women and children, participated in the show. The Indian village, populated mainly by the Lakota Sioux, was as huge a draw as the mock battles. Entering the show grounds just off Boulevard Victor Hugo, visitors walked past the tents of Cody, Annie Oakley and the cowboys to a large plaza filled with the Indians’ tipis, revealing how the tribes lived back on the Plains.

After passing through this area, visitors entered the arena where the show was staged. A map provided in the 1889 program shows that the arena took up less than 50 percent of the grounds, which also offered opportunities to visit a buffalo enclosure and extensive horse stables. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was much more than a “show,” a word publicist John Burke avoided in all marketing and even threatened employees with dismissal if they used the word.

Cody was the most popular attraction, taking part in battle re-enactments, demonstrating buffalo hunts and chatting with visitors to his tent.

Sharpshooter Annie Oakley was a close second in popularity. The French were fascinated by this petite young lady who could outshoot any man alive at the time. Oakley arrived in France with a secret. French law forbade the import of gunpowder, so she smuggled in her favorite British gunpowder, hidden in hot water bottles under her bustle.

More than six feet tall, Buck Taylor, nicknamed the “King of the Cowboys,” towered over his fellow performers as well as most of the European visitors. The skill of this cowboy, sitting so tall in the saddle, greatly impressed an audience still dependent upon horsemanship for everything from transportation to recreation.

Taylor contrasted with young Johnny Baker who, at age 19, was billed as the “Cowboy Kid.” Baker, who learned shooting from Cody and Oakley, had become a crack shot, coming near to rivaling them in marksmanship.

The Paris Performance

The Wild West opened with the “Star Spangled Banner,” followed by a grand procession of all of its participants. The first act was a pony race, pitting an Indian, a Mexican vaquero and a cowboy against each other. Unlike the battles, which had a predictable conclusion (Cody’s side always won), any of the three could win the race.

The first shots were provided by Oakley, whose ladylike demeanor helped ease any Victorian anxieties caused by the gunfire.

Following a demonstration of a Pony Express ride, the first battle was fought, an attack on an emigrant family in a wagon by “marauding Indians.” The Indian contingent was led by Lakota Chief Red Shirt. Lakota holy man Sitting Bull had been part of the Wild West in 1885, but he was no longer with the show. Red Shirt, who was well-spoken and comfortable in cross-cultural contexts, was probably a better representative than the gruff Sitting Bull. He had even visited Parliament during the show’s stay in London.

The gunfire in the show was broken up by quieter activities. Following the attack on the emigrant family, cowboys and cowgirls danced the Virginia Reel on horseback. The Cowboy Kid’s marksmanship was followed by “Cowboy Fun,” which featured ranch skills that included bronco riding and lassoing. This portion of the Wild West is considered a forerunner of modern professional rodeo.

As the show reached its climax, the Deadwood Stage entered the arena at breakneck speed, pursued by whooping Indians. Driven off by Cody and the cowboys, the Indians returned to demonstrate bareback racing and their tribal dances. Following presentations of sharpshooting and buffalo hunting by Cody, the grand finale was an Indian attack on a settler’s cabin. Once again, the Indians were driven off by the show’s star and “Le Roi des Hommes de la Frontière,” Cody.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was unlike anything the French had seen before. Among the thousands who flocked to the show were royalty and dignitaries from the continents of Europe, Asia, Africa and North America. Even the English, who had seen it two years before in London, came to France for a second viewing. The opening on May 18 was attended by French President Marie François Sadi Carnot and the American ambassador, as well as former Queen Isabella II of Spain. Powerful, famous and everyday people caught “Wild West fever” and converged on the show until its close six months later.

Lasting Impressions

The exposition not only catapulted Cody into the spotlight, making him the toast of Paris and adding to his credibility back home in America, but also gave him a chance to interact with the movers and shakers of his day. In Paris, Cody made his first acquaintance with inventor Thomas Edison, while throwing a Western breakfast of buffalo in his honor. Edison later recorded both the Wild West and Cody himself on Edison’s new moving picture and sound recording inventions.

The Wild West was not without its influences upon the many artists who visited Paris for the exposition. While American artist Whistler never got around to painting his portrait of Cody in London, renowned French artist Rosa Bonheur created what has become one of her most famous works, a portrait of Cody on his horse Tucker. Edvard Munch, who had left his native Norway to study art in Paris, was much impressed by Cody and his Wild West. Who knows how that singular experience may have influenced Munch’s work, including his most famous painting, The Scream, created just a few years later.

French painter Paul Gauguin, friend to Vincent Van Gogh, was probably the most deeply impressed among the artists who visited the Wild West. After his first visit, he wrote another artist friend, urging him to join him in a second visit, remarking that the show was “hugely interesting.” His enthusiasm led him to purchase a Stetson. A self portrait, done on the French Polynesian island of Tahiti four years later, shows Gauguin wearing a hat that looks remarkably like Stetson’s “Boss of the Plains.”

Shot in the Heart

On November 14, 1889, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West closed its attraction in Paris, France, and moved on to other European destinations. During its run, the residents of Paris had certainly fallen in love with the Wild West. Perhaps their hearts had been struck by the “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin,” a concluding shoot-out between the Indians and the cowboys, led by Cody, that had the greatest impact on audiences.

Months later, a shoot-out inspired by the Wild West might very well have become responsible for the death of one of Europe’s greatest artists, Vincent van Gogh.

But during the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, that final shoot-out scene promoted a victory of America’s pioneer experience that Parisians could share with Cody. In the arena, they witnessed the danger and excitement that Parisians had only read about. History leaped from the pages.

– All images courtesy Buffalo Bill Museum & Grave in Golden, Colorado, unless otherwise noted –

– Illustrated in the June 19, 1889, edition of the satirical Puck magazine –

Steve Friesen is the director of the Buffalo Bill Museum & Grave in Golden, Colorado. Research for this article informed, “From Prairie to Palace: Buffalo Bill in Europe,” on exhibit until January 20, 2017.