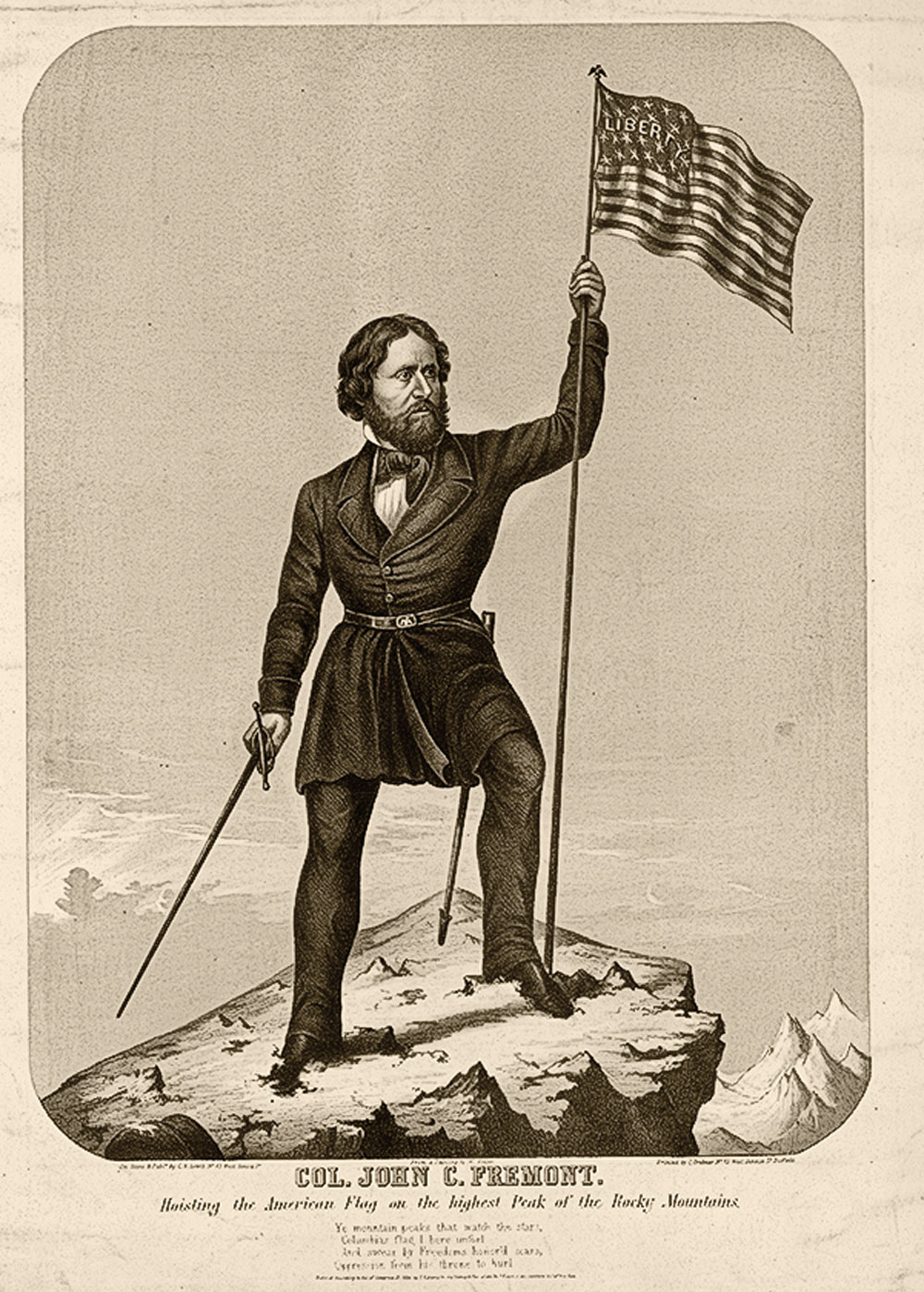

flag on one of the range’s peaks, today known as Fremont Peak.

– Wind River Range True West Archives –

In September 13, 2001, two days after a horrific attack of terrorism tore at the core of our nation, I did what other Americans did: Got up and went to work. On this day, doing research for a book and a True West article, I drove through the Colorado Rockies, visiting ghost towns and still-vibrant communities. I stepped into a small chapel in Cripple Creek at noon to pray with people I did not know for a nation still reeling from the attacks of 9/11.

In the afternoon, I drove to the top of Pikes Peak. I had never been there. I had dutifully listened to the warning given at the base of the mountains: Be careful on the descent. Don’t use your brakes too much; they could get hot and give out. It is a steep road.

At the top of the mountain, I left my car to take in the grandeur. It felt like I had the entire mountain to myself; the wind buffeted, but the view inspired. This was where America’s anthem was penned. This mountain was where explorer/adventurer Zebulon Pike had come in 1806, the first Euro-American to trod the rocky landscape. This was where the ancestors of my dear friend, Northern Ute spiritual leader Clifford Duncan, came for sustenance and ceremony.

The pre-autumn air was chilly, but standing there on that mountain was healing. The mountain itself inspired strength, resolve. The tears that ran down my cheeks as I stood alone on a mountaintop were a release from the tension of the prior two days since America had been attacked. But I knew then that as long as we had these natural landscapes, these places of respite, our souls and resolve would remain strong. It was a powerful, healing moment.

As John Muir so accurately phrased it: “The mountains are calling and I must go.”

I have always lived in the mountains. Even during my four years away from “home” for college, the mountains were visible; a drive of less than an hour could put me in the Sunlight Basin of northern Wyoming or high in the Snowy Range of southern Wyoming. The peaks of the Rockies always have been tangible and tempting, though I am a road warrior, not a mountain climber, so I freely admit my exploration of them has been by road tripping, not hiking.

The Utes call the mountain we recognize as Pikes Peak, Tava. For them it is where they came to this world and it became a fortress against their enemies. The massive peak awed and inspired 19th-century explorer Zebulon Pike and his name is attached to this landmark west of Colorado Springs. Pikes Peak inspired Katherine Lee Bates, and her anthem “America the Beautiful” made it America’s Mountain.

– True West Archives –

The new visitor center atop Pikes Peak will interpret all of these themes: “The Place, A Sacred World, An Empire for Liberty, America’s Mountain, and The Pike Today.” It is a good place to begin a journey to some of the great peaks of the Rocky Mountains.

From Pikes Peak, head north on Highway 67 toward Woodland Park, and continue to Idaho Springs, then take Highway 119 to Blackhawk. This peak-to-peak highway ultimately passes Longs Peak named for Stephen Long, who first spied it on his explorations in 1820, and takes you into Estes Park. The route is through the Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest. Leaving Estes Park, travel on US 34—Trail Ridge Road, the highest elevation highway in the country—through Rocky Mountain Park to Grand Lake and Granby, before turning north through North Park and into Wyoming.

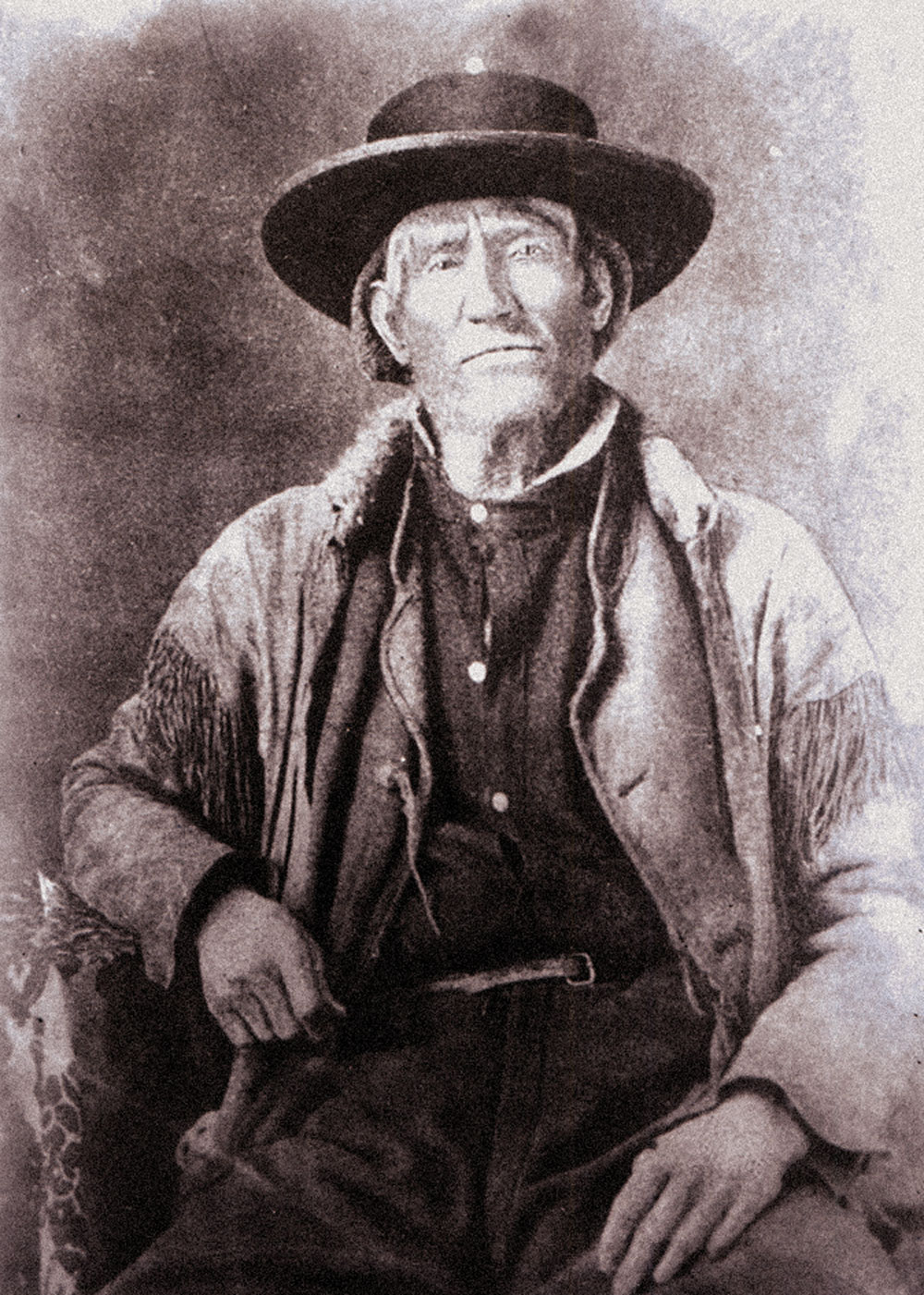

Jim Bridger came west in 1825 as one of William Ashley’s “enterprising young men.” For the next 40 years, Bridger traipsed throughout the Rocky Mountains trapping beaver, exploring, leading parties of emigrants, drawing maps, learning the country. And his name is attached to Bridger Peak along the Continental Divide, midway between Encampment and Savery, Wyoming.

A mountain man rendezvous takes place at the Grand Encampment Museum in late July each year. This modern-day gathering features black-powder shooting, a trader’s row where you can purchase mountain goods from moccasins to felt hats and capotes. The Little Snake River Museum in Savery has the original cabin built and used by mountain man James Baker, one of Baker’s guns and other exhibits including one newly opened in August that focuses on the sheep ranching industry.

– True West Archives –

Continuing north through Rawlins, take Highway 287 to Lander. The mountains to the west are the Wind River Range, location of Fremont Peak, named for John C. Fremont, who left Washington, D.C., on May 2, 1842, traveling to St. Louis where he spent nearly three weeks at Chouteau’s Landing. There he organized and equipped a party that included German cartographer and scientist Charles Preuss and Kit Carson, who would serve as the primary guide as Fremont explored the West. This first exploratory trip by Fremont took him over the route of the Oregon Trail. In Wyoming, Fremont followed the North Platte and Sweetwater rivers, which led him to South Pass. Then he turned north into the Wind River Mountains, placing a flag on one high summit that ultimately became Fremont Peak, before returning to the east.

The following year, Fremont came west again, this time initially guided by mountain man Thomas “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick, and again accompanied by Preuss, who collected plant specimens, made topographical sketches, and undertook other scientific explorations. Carson was along as well, and he also served as a guide for Fremont.

The South Pass region became the main route for pioneers traveling to Oregon, argonauts headed to California’s gold rush, and Mormons en-route to the Great Salt Lake Valley. Gold discoveries in the area at the end of the overland trail period, led to the establishment of South Pass City, now a Wyoming State Historic Site.

– Pike’s Peak by William Henry Jackson Courtesy Library of Congress –

Harry Yount served in the Union Army during the Civil War. He was captured and held in a Confederate prison but was released in a prisoner exchange and returned to fight for the Union. After the Civil War, Yount came west with the Hayden Geological Survey. He spent years trapping and prospecting before Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz hired Yount as the first gamekeeper in Yellowstone National Park in 1880.

Yount earned the nickname “Rocky Mountain Harry Yount,” and Horace Albright, the second director of the National Park Service, called him the “father of the ranger services,” as well as the first national park ranger. During the Hayden Survey his name was attached to Younts Peak, the highest peak in the Teton Wilderness between Jackson Hole and Cody, Wyoming, and near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River.

The peaks of the Rockies named for explorers and adventurers Zebulon Pike, Stephen Long, Jim Bridger, John C. Fremont and Harry Yount are just a few of the many craggy landmarks on the peak-to-peak route.

in the wilderness on back roads; book a room at the renowned Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, Colorado,

and enjoy a retreat in one of the West’s most luxurious hotels.

– Courtesy Gates Frontiers Fund Colorado Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress –