— Courtesy National Archives and Record Administration, No. 594940 —

“It is done!”

These three words shot out across the Western telegraph to the world on May 10, 1869, at the moment Central Pacific Railroad owner Leland Stanford’s specially wired silver-topped ceremonial hammer careened past the side of the ceremonial Golden Spike and struck the recently laid iron rail connecting the C.P.R.R. with the Union Pacific Railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory. Known as The Pacific Railroad, the monumental engineering feat was as inspiring to the young, war-weary nation as the U.S. Apollo 11 landing on the moon a century and two months later. And like President Kennedy’s audacious September 12, 1962, declaration that America would put a man on the moon before the end of the decade, President Abraham Lincoln had put the transcontinental railroad on track to reality when he signed the Pacific Railroad Act on July 2, 1862.

One hundred and fifty years later, the original hand-forged spike sits on display at Stanford University’s Cantor Art Center, as does a duplicate—donated by the heirs of the spike’s sponsor, San Franciscan David Hewes—at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento. On one side of the spike simple words commemorate the significance of the transcontinental line’s completion: “May God continue the unity of our country as this railroad unites the two great oceans of the world.” These prophetic words underlay a nation’s hope in the midst of rebuilding from the horrors of the Civil War, struggles of Reconstruction, mass immigration, industrialization, and racial, tribal, ethnic and labor conflicts in 1869. Why, even a few days before the conjoining of the two railways on the original date of May 8, a U.P. labor dispute arose and delayed the laying of the final tracks, ties and spikes. Americans in 1869 needed the boost and grand reminder of their nationhood and shared destiny.

Now, the sesquicentennial of The Pacific Railroad’s completion will be celebrated with great fanfare and ceremony at Golden Spike National Historic Site at Promontory Summit, near Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 2019. Replicas of the C.P.R.R.’s Jupiter and U.P. No. 119 locomotives will be driven cowcatcher to cowcatcher, and national park staff and volunteers will re-create the momentous occasion to mark the day the United States was united, coast-to-coast, by iron rail. The bell-ringing, hurrahs and huzzahs from the single-day event should herald a national invitation to plan a Western trip and follow the celebrated route between Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Sacramento, California, west to east or east to west, and rediscover how a nation was united 150 years ago through collective sacrifice, ingenuity and hard work.

As the sun set on the Golden Spike ceremony at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, the evening of May 10, 1869, the United States of America was now conjoined in iron rail from the Atlantic to Pacific. As Chief Engineer Grenville M. Dodge wrote in his telegraph wire to Gen. John A. Rawlins, Secretary of War:

“At 12 o’clock M. to-day the last rail was laid at this point, 1,086 miles from Missouri River and 690 miles from Sacramento. The great work, commenced during the administration of LINCOLN, in the middle of the great rebellion, is completed under that of GRANT, who conquered the peace.”

Utah’s Spike 150!

— Photos Courtesy NPS.gov —

One-hundred-and-fifty years later, the Golden Spike Foundation, in cooperation with multiple agencies and community organizations—including the state of Utah, Union Pacific Railroad, the national park service and the Mormon Church—have scheduled events across Utah and throughout 2019 to commemorate the sesquicentennial of the transcontinental railroad’s completion.

To open the week of Golden Spike Sesquicentennial celebrations, on May 4 Box Elder County is hosting a horse parade showcasing the lifestyle of 1869 with authentic period dress and equipment from each of Utah’s 29 counties in Brigham City. In the evening, a good old-fashioned hoedown will be held at the Box Elder County Fairgrounds Event Center in Tremonton.

On May 10-11, 2019, a 150-year anniversary celebration weekend will take place at Golden Spike National Historic Site, Promontory Summit, Utah. Visitors will be able to step out onto the site where history was made, partake in activities, meander through the visitors center and monuments and visit the nearby Chinese dugouts and Spiral Jetty.

Between Memorial Day and Labor Day 2019, visitors from Utah and beyond can come to Golden Spike National Historic Site and the Promontory Summit area and tour where history was made, partake in ongoing Spike 150 Commission commemorative experiences, walk through the visitors center and monuments and visit the nearby Chinese dugouts and Spiral Jetty.

For more details on these and all events throughout the year, visit the website Spike150.org.

The Central Pacific Starts in Old Sacramento

— Courtesy Stanford University Library —

Gold Rush entrepreneurs Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker and Collis P. Huntington, formed the Central Pacific Railroad Company in Sacramento, California, on April 30, 1861. Soon to be known as “The Big Four,” the quartet would oversee the politics, construction, financing and labor of the Western half of the Pacific Railroad.

Today, with the duel 170th anniversary of the Gold Rush and the 150th anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad, a tour of the Golden State from Old Sacramento, through Gold Country and across the Sierra Nevada to Reno, Nevada, will provide the heritage traveler with an understanding of the connection between the four Gold Rush merchants and the Central Pacific’s construction from January 1863 to May 1869.

A sesquicentennial Central Pacific Railroad history tour should begin at the California State Railroad Museum at Old Sacramento. With Leland Stanford’s famous locomotive as the centerpiece of the museum’s C.P.R.R. exhibition, a series of events will be held in April and May 2019 in celebration of the historic feat of engineering. Special exhibitions on the C.P.R.R. will include a newly designed interactive exhibit featuring the “lost” Gold Spike, an exact duplicate cast at the same time as the one used at Promontory Summit; a new exhibition on the Chinese workers’ experience building the C.P.R.R; and on loan from the California State Archives, the debut of the C.P.R.R.’s first engineer Theodore Judah’s complete 1866 map of the Sierra Nevada and route of the railroad.

On May 8, 2019, a major celebration free to the public will be held at Old Sacramento including the historic re-creation of the parade that took place on May 8, 1869; complimentary excursion train rides aboard the Sacramento Southern Railroad throughout the day; melodrama perform-ances at the historic Eagle Theatre; and

a community picnic to which guests can bring a sack lunch to enjoy on 1849 Scene (a large grassy area in front of the Railroad Museum) and enjoy live music and entertaining stories from historians and docents on the building of the railroad.

For more information on sesquicentennial exhibits, events and activities at Old Sacramento and the California State Railroad Museum, visit the website Railroad150.org.

Over the Sierra to Nevada

— Snow Plow photo Courtesy Stanford University Library/Photo of Donner Pass, True West Archives —

Whether taking the train or driving Interstate 80, the route east from Sacramento parallels much of the historic California Trail, Central Pacific and Lincoln Highway (U.S. 40) corridor across California and Nevada (until its junction with Nevada 233 east of Wells). Colfax, one of the oldest Gold Rush camps where the original Central Pacific built a station in December 1866—and is still served by passenger service—is less than an hour from Sacramento. The town was first known as Alden Grove in 1849 and quickly became a supply center during the Gold Rush and railroad construction. A walking tour of Colfax’s historic downtown should include the 1905 Southern Pacific train station, Colfax Heritage Museum and a side trip to the Empire State Mine State Historic Park, just nine miles up the mountain on scenic California Highway 49.

With Colfax as its staging area at the beginning of 1867—just 54 miles from Sacramento—the rail crews blasted and hammered across the Sierra to Donner Pass and Truckee. At the same time, Chinese and Anglo crews were digging

and blasting the Summit Tunnel westward—1,659 feet through the mountain at Donner Pass. Tunnel No. 6 was finished on August 28, 1867 and the rail line arrived at the west entrance on December 1. Six months later, on June 18, 1868, the first C.P.R.R. train brought passengers to Lake’s Crossing—the future town of Reno, Nevada. The Big Four’s engineers and labor crews—80 percent of whom were Chinese—had solved the Sierra’s unforgiving winters and rugged terrain with innovation and invention, including 38 miles and 65 million board feet of custom snowsheds.

If you like scenic switchbacks, take Exit 174 at Soda Springs and take Donner Pass Road to Donner Lake, Donner Memorial State Park and Emigrant Trail Museum. Historic downtown Truckee has a great selection of restaurants and inns, as well as the finely appointed and informative Truckee Railroad Museum in a former Southern Pacific caboose adjacent to the historic train depot.

Nevada’s Historic Rail Corridor

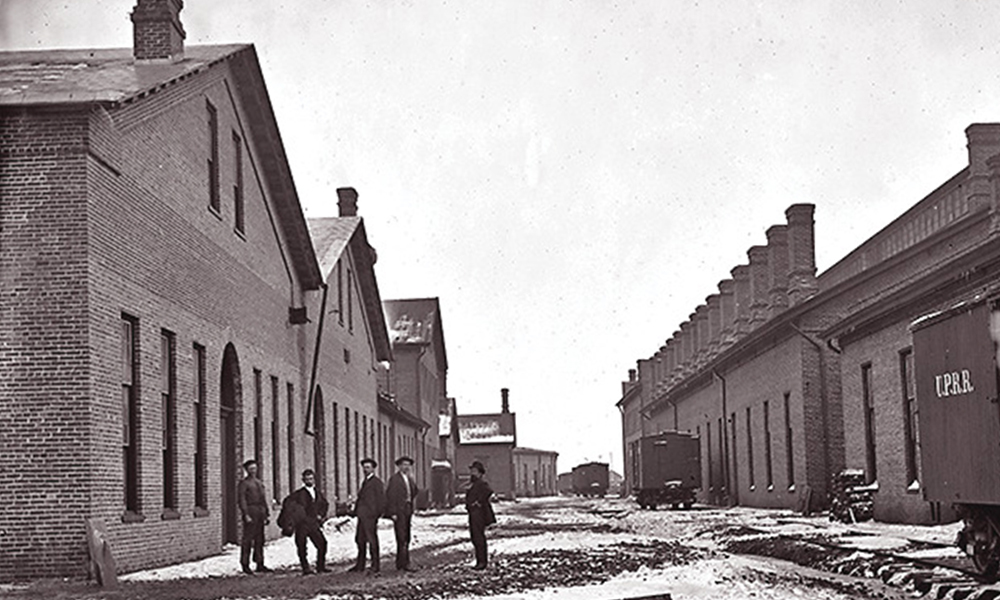

— Alfred A. Hart, Courtesy Stanford University Library —

Many states can trace their rise in economic influence and development to the transcontinental railroad, but one young, lightly populated state that benefited

immediately, and still does today, from the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad was Nevada. With its highly valuable gold and silver mines of the Comstock Lode, the Silver State had been rushed into statehood in 1864, just three years after it was made a territory. The C.P.R.R.’s route paralleled the highly traveled California Trail—and its

key sources of water and springs—from the Western state line with California to near Wells, where the rail route tracked northeastward on a new track across the desert to north of the Great Salt Lake.

The Central Pacific rail crews arrived in Nevada in early 1868, but with only 140 miles of track in place at the beginning of the year, the Big Four still had more than 550 miles to go to meet the Union Pacific—which had already raced 500 miles across the Nebraska plains to southeastern Wyoming Territory. The harrowing, dangerous and time-consuming work from Sacramento to build and blast over the Sierra had taken five years since the ceremonial groundbreaking, but soon the Big Four’s Central Pacific work crews would benefit from relatively flat Nevada desert, while the Union Pacific construction crews would experience the geography of Wyoming and Utah territories—and the challenges and painstaking delays from bridge and tunnel construction.

Like its sister Union Pacific, the Central Pacific had a “Hell on Wheels” community in Nevada of merchants, entrepreneurs, grifters, gamblers and prostitutes ready

to set up camp at each new C.P.R.R. town. Travelers following the railroad’s construction progression across the state’s northern deserts on Interstate 80 can follow Nevada’s Cowboy Corridor Scenic Byway from Reno to Wendover. Before leaving from Reno, schedule time to tour historic Carson City and Virginia City, including a ride on the historic Virginia & Truckee Railroad that connects the state capital to the “capital” of the Comstock Lode. Carson City is home to the Nevada State Museum and Nevada State Railroad Museum, while Virginia City’s downtown is part of a larger National Historic Landmark district that also includes the legendary mining camps of Gold Hill, Dayton and Silver City.

Highlights not to miss while retracing the Central Pacific’s progress across Nevada include the Chinese cultural exhibit at Winnemucca’s Humboldt County Museum; Battle Mountain’s Depot and Mining Museum; Elko’s Western Folklife Center and California Trail Interpretive Center; and the Lamoille Canyon Scenic Byway in the Ruby Mountains south of Elko.

Travelers following the C.P.R.R. across Nevada to Promontory, Utah, hit a historical crossroads 27 miles from Wells at the aptly named town of Oasis. Go northeast on Nevada 233 to Utah 30 to I-84 and Utah 83 to Golden Spike National Historic Site (and access to the off-road, BLM-managed Transcontinental Railroad Back Country Byway), or continue east on I-80 to Salt Lake City and its junction with I-15 north through Ogden to Brigham City and Utah 83, exit at Corinne to complete the drive to Promontory.

Before leaving Nevada, historic railroad buffs should consider scheduling extra days and time to drive 140 miles south of Wells on legendary U.S. 93 to the mining-rail town of Ely, home to the Northern Nevada Railway, a national historic landmark that is one of the finest heritage short lines and railroad museums in the United States.

The Union Pacific Starts in Council Bluffs

Future President Abraham Lincoln visited Council Bluffs, Iowa, in August 1859, and had an influential meeting with railroad engineer Grenville Dodge. At the meeting Dodge told Lincoln the best route West was from Council Bluffs west across Nebraska. Destiny was set in motion that day—and when Lincoln signed the 1862 Pacific Railroad Act—he designated the Iowa city the starting point for the transcontinental line. Fate would have it that a bridge across the river would not be built until 1873, so the Union Pacific railroad physically started from Omaha—and that is where it is presently headquartered.

Today, visitors to Council Bluffs can learn about the history of the Union Pacific and transcontinental railroad at the Union Pacific Railroad Museum, Bayliss Park, Golden Spike Monument, Historic General Dodge House and the Lincoln Monument, built near the location the future president would first visualize the construction of the Pacific Railroad. Just across the river in Omaha, is the Durham Museum in the city’s beautifully restored Union Station. (See Jana Bommersbach’s column on the Durham and a special U.P.R.R. exhibit on p. 12.)

Nebraska’s Destiny as a Railroad State

— Photo of Bailey Train Yard Courtesy Nebraska Tourism/Photo of Omaha Train Yard by Andrew J. Russell Courtesy Oakland Museum of California —

Omaha, Nebraska, has been a Western gateway-crossroads city since it was founded on July 4, 1854. With great commercial, financial and cultural ties to its neighbor across the Missouri River, Council Bluffs, Omaha’s earliest residents knew its potential with broad open lands ready for development adjacent to the delta of the Platte River with the Missouri.

On July 10, 1865, the Union Pacific began laying track and ties from Omaha west and sped across the Cornhusker State to the Wyoming Territory in 16 months, arriving in Cheyenne on November 13, 1867. What was once known as Crow Creek Crossing, would quickly grow into the territorial capital of Wyoming and one of the U.P.R.R.’s most important rail centers on its inaugural route.

The Nebraska section of the U.P.R.R. followed the arc of the Mormon Emigrant trail on the north bank of the Platte River from Omaha to Ames, Fremont, Columbus Grand Island, Kearney and Cozad to North Platte where the railroad diverted from the Overland Trail to follow the South Platte and a series of drainages west. North Platte became a key Union Pacific rail center with a roundhouse, and today is home to the Bailey Railyard, the world’s largest. Don’t miss a tour with the great views from the Golden Spike Tower Visitor Center of the rail center, the Platte River Valley and 360-degree view of the Great Plains.

Crossing the Cowboy State

— Andrew J. Russell, Courtesy Oakland Museum of California —

West from North Platte, the U.P. tracks went west from the South Platte River into Colorado and the town of Julesburg in June 1867. The one and only Colorado railroad town on the Union Pacific line, it quickly gained a reputation as a wild camp. Today, visitors can learn more about Julesburg’s role in railroad and Colorado history at the Fort Sedgwick and Depot Museum.

Crossing into Wyoming Territory, the Union Pacific rail crews realized some of its greatest engineering challenges as it founded significant railroad towns en route to the Utah Territory. In 1867, Cheyenne and Laramie became key railroad hubs in southeastern Wyoming as the U.P. engineers and rail crews worked to cross Dale Creek, near Sherman. A mile of granite had to be blasted out for the rail bed on both sides of the bridge, which, at 150 feet, was the longest of the rail line. Completely built of timber, the engineering wonder was known to sway as trains crossed it and in 1876 its timbers were supplanted with an iron bridge.

In Cheyenne, take a tour of the Cheyenne Depot Museum in the historic Union Pacific Railroad station, including its historic locomotive exhibit. Laramie also has one of the state’s finest railway museums, at the Laramie Historic Railroad Depot.

Driving west on I-80 from Laramie to the Utah state line, the route parallels the original U.P.R.R. Excellent historic sites and museums that tell the story of the Union Pacific and the settlement of the state of Wyoming include the Carbon County Museum, Rock Springs Historical Museum and Fort Bridger State Historic Site.

Utah’s Wasatch Mountains

— Courtesy Union Pacific Railroad Museum —

In the summer and fall of 1868, the Union Pacific crossed the continental divide in southwestern Wyoming and began construction in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains. With a close eye on the Central Pacific working quickly across Nevada’s highly gradable northern desert, the Union Pacific now had to blast and bridge its way across and through the same range that westbound emigrants, forty-niners and Mormon pioneers had struggled through for decades to reach Salt Lake City and trails west. Engineers blasted through the mountains, including Tunnel No. 2 in Weber Canyon, which was started in October

and completed in the spring of 1869. One of the worst winters in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains slowed the U.P., which in 1868 had built 425 miles of track. In the spring, the railway would emerge from the mountains and lay track to Ogden, north to Brigham City, Corinne and its date with destiny at Promontory Summit.

Today, rail enthusiasts who want to drive a route parallel to the original U.P. route should follow I-80 west from Evanston, Wyoming, through the Wasatch Mountains to I-84 north to Ogden’s Union Station, an excellent rail museum, and center of numerous sesquicentennial events in 2019. North from Ogden, the town of Corinne was the first founded in the territory by non-Mormons, and has a nice local museum to visit, as do nearby Brigham City and Tremonton, on the way to the historic end of the Union Pacific at Golden Spike National Historic Site at Promontory Summit.