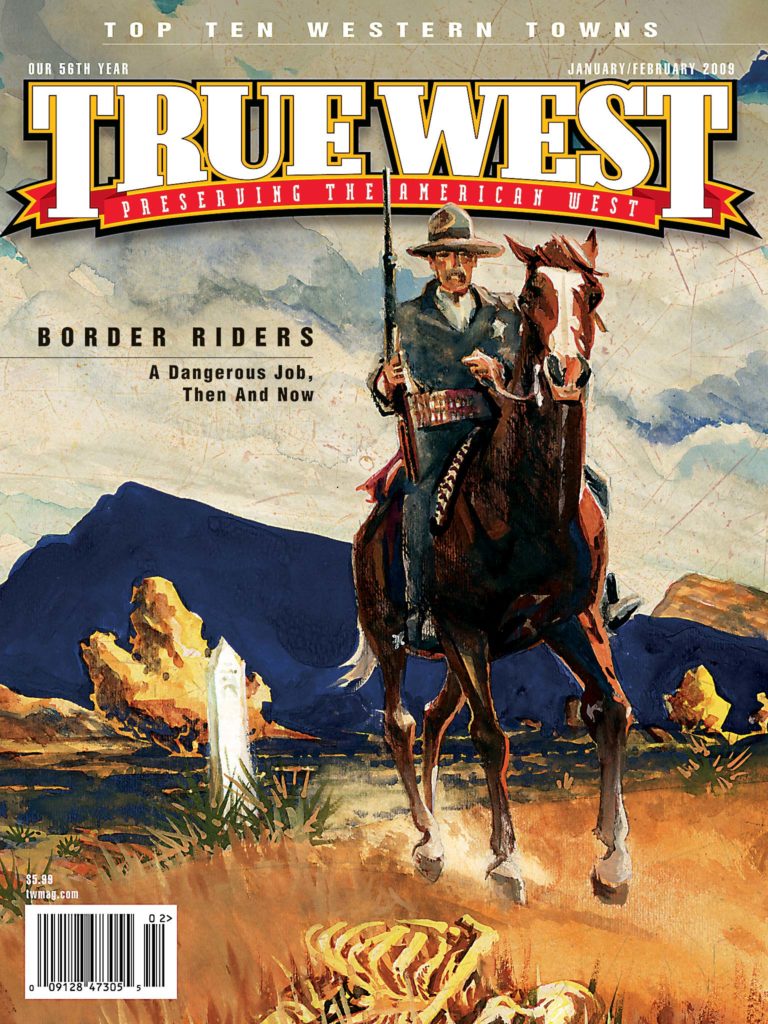

After a hard day of patrolling his 80-mile section of the 4,000-mile border between the U.S. and Canada, this U.S. Border Patrol employee is grateful for his room, board, shoes and a little hay.

Hay? It’s the perfect food for a hardworking Mustang in service under the U.S. Border Patrol.

Project Noble Mustang, launched the summer of 2007, helps the Spokane Sector Border Patrol of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection fulfill its mission, while showcasing the Mustang, America’s wild horse. Wild Mustangs are adopted from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), gentled by inmates in Colorado and are used by Border Patrol agents to monitor the Spokane sector’s remote backcountry. According to the agency, “Adopting these horses for patrolling the northern border blends today’s technology with yesterday’s traditions to create an effective component that provides seamless border enforcement.”

The Glimmer of Hope

Years ago, our shared border with Canada had few agents and no horses, as resources were concentrated on the Mexican border to stem the tide of illegal immigrants, smuggling and drug running. In 1999, northern horsemen agents decided to ride their personal mounts in parades. “A couple of us owned horses that we’d ride in parades as a public outreach,” says Lee Pinkerton, assistant chief of the Spokane sector.

But the 9/11 terrorist attack on America made border security a national priority. Canada, an immigration haven, even for individuals from countries suspected of supporting terrorism, became a greater concern. Early in 2001, only 340 agents were assigned along the northern border. Today, the Border Patrol numbers more than 1,100 agents, with plans to eventually number 1,845 by 2009, almost a six-fold increase from 2001.

Suddenly, parades weren’t the only use agents found for their steeds. The Spokane sector of the Border Patrol is responsible for 308 miles of northern border, stretching from the Cascade Mountains in eastern Washington to the Continental Divide in Montana. Two units, Oroville and Whitefish stations, of the Spokane sector’s seven areas, monitor the border in wilderness areas and national parks where motorized vehicles aren’t allowed. Even in areas not designated as wilderness, the terrain is often unsuitable for vehicles. Horses seemed a natural choice for transportation according to Pinkerton. “The area is very rugged and steep, so we needed a horse that was durable enough to withstand daily patrols in extreme terrain.”

Horses proved useful in the Spokane sector, currently the only northern sector using mounted patrols. “We’ve been leasing horses from local ranches since 2004,” says Danielle Suarez, senior patrol agent and Spokane sector Public Affairs officer. “They give us access to areas we can’t reach any other way.”

But this access was expensive. In 2006, each of the sector’s seven units received $25,000 to lease horses, which cost about $150 per animal daily. Familiar with southern Border Patrol horses, Pinkerton thought owning horses might be more economical. Project Noble Mustang came out of Pinkerton’s search for the ideal horses to own. “The cost, availability of horses to fit my needs, plus the fact that these horses need homes, made Mustangs a good choice.”

A Wild Idea Into a Brilliant Solution

Mustangs developed through natural selection. The first wild horses in the Americas were escapees from the Spanish Conquistadors’ hardy Iberian Sorria (“Saving America’s First True Horse”). As other settlers arrived and lost horses, the wild horse got infused with a variety of work and saddle horse breeds. Settlers and American Indians caught and tamed Mustangs, using them as stock for American breeds such as the cowboy’s Quarter Horse and the Nez Perce’s Appaloosa.

As prey animals, Mustangs needed to be quick and tough, developing large, hard hooves and big, sturdy bones (although they were relatively smaller compared to their Quarter Horse relatives). They were resistant to disease, had great endurance and could subsist on poor or little feed. Mustangs had to be surefooted and alert to their surroundings. “It was survival of the fittest, with toughness and durability being bred into the Mustang,” says Fran Ackley, who manages Colorado’s Wild Horse and Burro Program for the BLM.

Mustangs have been protected since 1971 under the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act. Grazing on generally arid government land in 10 western states, the wild population of about 29,500 wild horses and 3,500 burros is managed by the BLM.

According to BLM calculations, available food and water can only sustain a population of 27,300. Left unmanaged, wild herds quickly outgrow their food supply and risk starvation. To control the population, the BLM periodically captures horses and offers them for public adoption. Despite an adoption fee of only $125, the BLM has more horses and burros than it has homes. The Spokane Border Patrol was able to adopt the kind of mounts needed at low cost and provide a home for Mustangs.

Project Noble Mustang has benefited both agencies in additional ways. “Mustangs have been a recruitment tool for the Border Patrol,” Ackley says, “and we’ve had people interested in Mustangs after seeing how trustworthy, trainable and reliable they can be for the Border Patrol.”

A partnership between the BLM and Colorado Correctional Industries allows inmates to train adopted Mustangs for a $900 fee as part of the Wild Horse Inmate Program (WHIP). Since 1986, WHIP has served the dual function of training Mustangs and rehabilitating prisoners.

In 2007, eight trained Mustang geldings arrived at the Spokane sector to serve as the foundation of the Noble Mustang Project. Their names were chosen by elementary school students from each of the seven border communities and a student from the headquarters area. A naming contest was held and Border Patrol agents visited classrooms to promote the contest and to share the story of the U.S. Border Patrol and Project Noble Mustang. The winning names were Chase, Slash, Hidalgo, Ike, Sisko, Spurs, Okanogan (“Oke”) and Kootenai (“Koot”).

Nation’s First Border Patrol

Although Project Noble Mustang is new to the Border Patrol, the use of horses is not. The Labor Appropriation Act of 1924 created the U.S. Border Patrol as a continuation of the “Mounted Guard” program that patrolled the southern border restricting the flow of illegal Chinese immigrants from Mexico. These first mounted guards included Jeff Milton, referred to as the “first Immigration Border Patrolman.” A tough lawman and one-time Texas Ranger, Milton started as a mounted inspector in 1887 along the Arizona-Mexico border. He eventually became a Border Patrol agent, continuing at his work until 1932. His and a few others’ valiant efforts ensured the Border Patrol’s success in its early years.

Since horses were such an integral part of the early years of the Border Patrol, they were treated humanely. Agents provided their own horse and tack, and the government paid for the feed. Today, Border Patrol agents provide for their Mustangs in the Spokane sector, as well as a number of various horse breeds along the southern border.

Mustangs Got the “Right Stuff”

Mustangs have proven to be the right choice for the Spokane sector and could prove the right choice for an expanded Border Patrol program. Mustangs are durable, strong and intelligent. Pinkerton describes them as “easy keepers,” meaning that the Mustangs are able to patrol daily in the mountains and keep their flesh and strength, compared to the weight loss seen in domestic horses. Their surefootedness makes them a favorite with Border Patrol agents, says Pinkerton, adding, “These animals are well adapted to the wilderness. And when you’re riding on a trail that’s 18 inches wide that drops off 2,000 feet, you want horses that watch where they put their feet.”

They also act as a force multiplier, increasing an agent’s detection ability. “Horses sense things far out of our capabilities,” Pinkerton says. “If you watch their ears, they’ll alert you to changes.”

Mustangs may even possess a sense of humor. Pinkerton tells a story about extolling the virtues of Mustangs, especially their surefootedness, while taking a reporter for a slow trail ride. Suddenly, Pinkerton’s gelding dropped to his belly. “All I can figure is he fell asleep. But I sure looked silly,” Pinkerton admits.

The Spokane Sector has found Project Noble Mustang to be so successful that the sector has increased its Mustangs from eight to 17 working in five of the seven units. Other northern border sectors, including the patrol in Blaine, Washington, have shown increased interest in mounted patrols, which could result in more jobs for Mustangs. Mustangs may eventually be used throughout the northern border “from Blaine to Maine.”

Southern Border Patrol stations are also incorporating Mustangs into their operations. The home of the nation’s first Border Patrol academy, El Paso, and the Del Rio sectors along the southern border have adopted a couple of Mustangs.

The Noble Mustang project has restored the use of mounted agents on the northern border and created a new tradition by adopting excess American Mustangs from one government agency and giving them a job with another government agency.

“Mustangs seem a natural fit,” Ackley says. “They were bred here, helped settle America and now they help patrol our borders.”

***

Mustang Makeover Redux

In October 2008, a government report pointed the way toward euthanizing the wild, formidable creatures so ingrained into our nation’s history.

The Government Accountability Office claimed non-compliance on the part of the BLM in managing what it deemed as an “excess” and “unadoptable” population of wild Mustangs and burros. It charged the agency with not fulfilling the directive to destroy excess animals, as amended to the 1971 Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act.

The Wild Horse and Burro Advisory Board responded in November with 19 recommendations for the BLM to consider as alternatives to euthanizing these animals. The BLM will discuss its assessment of these suggestions at the next board meeting, which will be held on February 23, 2009, in Reno, Nevada.

Missing among these prudent options is another one we’d like to suggest:? an investigation into expanding the mounted Border Patrol program. As demonstrated by the Spokane sector discussed in this article, mounted border agents could patrol terrain not accessible to motorized vehicles and, at the same time, this program could provide a healthy use of our nation’s first horse. Yet we cannot ignore the precious resources our wildernesses along the border provide us as a nation. The use of Mustangs may be among our best options for leaving the least environmental impact as we patrol these sectors of our borders. Given the importance of safeguarding our national security, an investigation should at least take place to determine if America’s first horse can lead us down the path to safety.

The BLM and the U.S. Border Patrol deserve our highest praise for finding inter-agency solutions to saving the Mustang. This thoughtful work must continue, with other agencies playing their roles in making this mounted border program viable and effective.

For now, the Mustangs and burros who faced lethal injection have found a reprieve, thanks to Madeleine Pickens, wife of wind tycoon T. Boone. She promised in November to adopt the 30,000 or so animals and let them run free out West.

What about tomorrow’s Mustangs? Write to your Congress representatives and senators, and let them know how they can better serve you—and the horse that you rode in on. —The Editors