The year was 1871, and the infamous James-Younger Gang was looking for some new revenue sources.

The boys had pretty much stuck to targets in their home state of Missouri during the first five years of their outlaw careers (they’d pulled one job in Kentucky). But they were about to go north. They were going to give Iowa a try.

April marks the 125th anniversary of the assassination of Jesse James by the coward Robert Ford (sounds like a movie title, doesn’t it?). Historians and aficionados are taking a closer look at America’s most “popular” outlaw. Because of this scrutiny, some of the gang’s lesser-known robberies, such as the two in Iowa, are being studied so as to provide a better understanding of these men and the lives they led. To some extent, Corydon and Adair have been somewhat overlooked—probably because the gang didn’t kill anybody during those robberies.

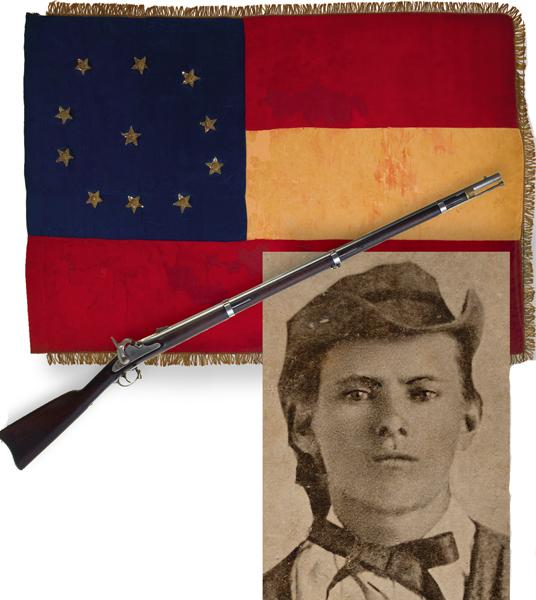

It was Jesse who conjured up the idea to rob a “Republican” state. He and the boys were confirmed Democrats—unreconstructed Rebels, former Con-federate guerrillas, pro-slavery—and almost all of their crimes were committed against Northern interests. In Missouri, the gang was extremely popular; pro-Southerners viewed them as freedom fighters, battling the occupying forces of the North. Going into Yankee Iowa would just strengthen the support they enjoyed back home.

The town of Corydon seemed a likely target. It was a flourishing little town just over the Missouri border where a considerable amount of business was transacted. “The year 1871 was a very important one to Wayne County,” recalled Corydon citizen E.A. Rea. “The Southwestern Railway Construction Company built the railroad that afterward became the Rock Island through the county…. The president of it asked the people of Wayne County to raise one hundred thousand dollars to assist in building the road through Wayne County. The first bank in Wayne County had been opened in Corydon in the fall of 1870 by Ocobock Brothers in a one-story frame building located on the corner…. A.W. Ocobock and Frank Boies of Chicago operated it.” So the town was close to the James-Younger base in northwest Missouri, and it was home to a bunch of Northern money, all waiting to be had.

“Just Come Down and Take Us”

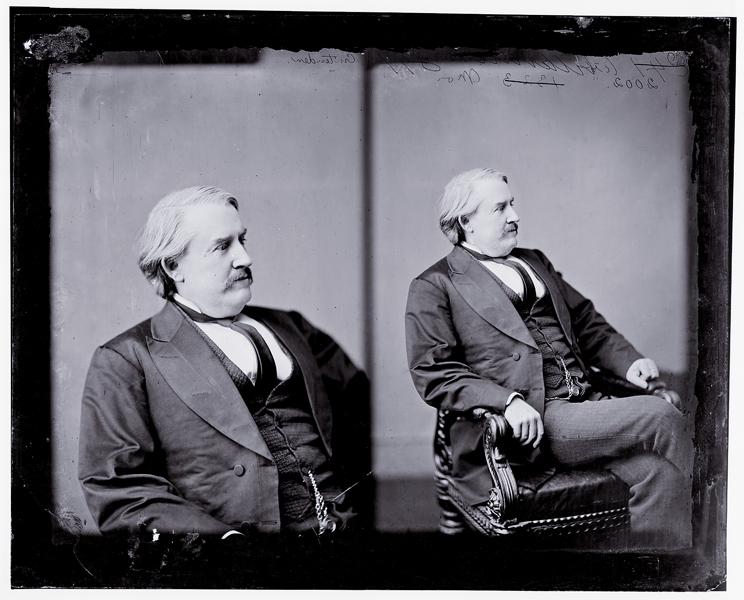

On June 3, 1871, about 1 p.m., Jesse and Frank James, Cole Younger and Clell Miller—well mounted and armed—rode slowly into Corydon. A meeting was in progress in the public square, called to induce local citizens to approve a tax to help build the Missouri, Iowa & Nebraska Railroad through town. It was well attended; Corydon’s population of about 625 swelled to 850. One of the big attractions: the verbal fireworks of celebrated orator Henry Clay Dean.

The outlaws stopped at the northeast corner of the square and entered the Wayne County Treasurer’s Office. Jesse asked the lone clerk if he could change a hundred dollar bill. The clerk said the safe was locked and the treasurer had gone to the town meeting; he directed them to the bank.

So they visited the Ocobock Brothers Bank near the northwest corner of the public square. Two outlaws entered the bank. Cashier Oscar Ocobock suddenly looked up the barrel of a large Colt revolver, which he later described as eight to ten inches long. It was held by a thickset, well built but not very tall, sunburned man—probably Jesse. The outlaws tied up Ocobock, emptied the loot into a sack and “appropriated” between $6,000-$10,000.

With masks covering their faces, they rode over to the square, brandishing revolvers. According to the local newspaper, Jesse apologized for interrupting Dean’s speech: “Well, you’ve been having your fun and we’ve been having ours. You needn’t go into hysterics when I tell you that we’ve just been down to the bank and robbed it of every dollar in the till. If you’ll go down there now you’ll find the cashier tied and then if you want any of us, why, just come down and take us. Thank you for your attention.”

The riders let out a wild yell, tipped their hats and galloped off. The crowd thought the interruption was an attempt to break up the meeting, so it took them a few minutes to get their bearings. Once they checked out the bank, a posse was hastily organized.

“The eloquence of Henry Clay Dean could not keep his audience after this,” E.A. Rea stated.

Young Adam Ripper was walking along the boarded sidewalk towards his father’s blacksmith shop when he saw horsemen galloping towards him. He realized the men were strangers in town—tall, good-looking fellows wearing broad-brimmed hats and carrying guns. As they swept past him, one of the men yelled, “We’ve robbed your bank! Catch us if you can!” The others whipped out their revolvers and fired “ringing” shots into the air. The robbers crossed into Missouri; darkness was setting in, making it impossible to track them.

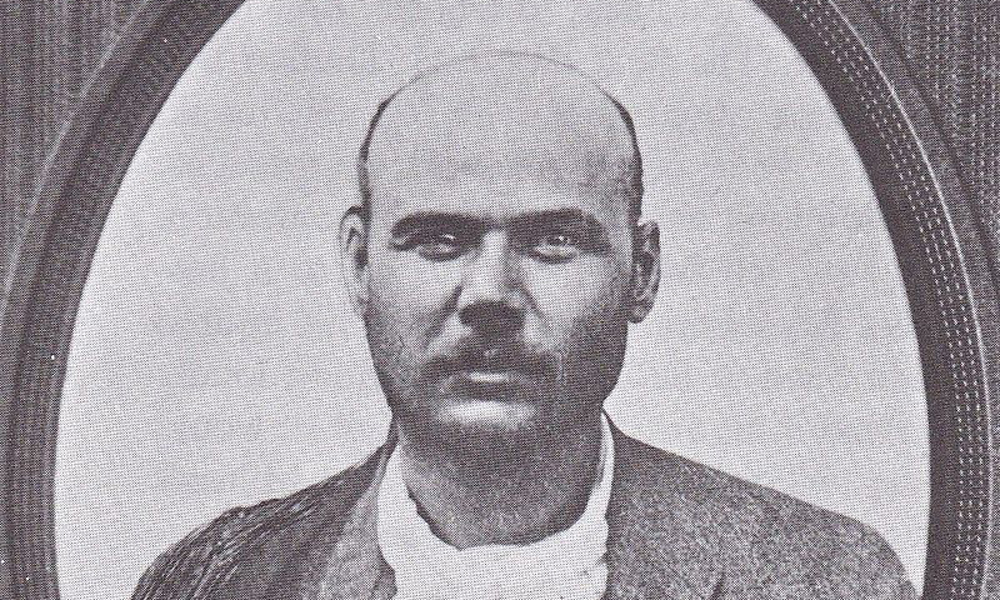

Two months after the robbery, a Pinkerton agent arrested Clell Miller in Clay County and eventually took him back to Corydon to stand trial on November 10, 1872, but Miller was found innocent. Following Miller’s acquittal, Jesse wrote the Kansas City Times, stating, “As to Frank and I robbing a bank in Iowa or anywhere else, it is as base a falsehood as ever was uttered from human lips.”

Falsehood or not, the James-Younger Gang wasn’t done with Iowa quite yet.

KKK Bandits

Early in July 1873, the outlaws learned that $75,000 in Yankee gold from Cheyenne, Wyoming, was to be carried through Adair, Iowa, on the recently built main line of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad. The gang, including Cole, Jim and Bob Younger, planned to strike the eastbound train outside Adair. The idea was probably Cole’s.

On July 18, a couple of the bandits rode into Adair posing as businessmen while Frank James and Cole Younger hurried to Omaha. They discovered the train would be carrying up to $100,000 in gold through Adair on July 21. In Casey, they purchased a rope at Valentine’s Hardware Store. Shortly after, they broke into a handcar house, purloined a spike-bar and hammer with which they pried off a fishplate connecting two rails and extracted the spikes at a curve of track near the Turkey Creek Bridge. The men quickly tied the rope to the west end of the disconnected north rail, passing the rope under the south rail to a hole they had cut into the bank in which to conceal themselves.

About 8:30 that evening, the train climbed a steep grade and approached the curve. Engineer John Rafferty saw the rope tied to the rail and immediately reversed his engine and applied the air brakes—too late.

The outlaws jerked the rail out of place, and the engine plunged into the ditch and toppled over on its side. The tender lay on top of the engine, bottom side up, and on top of the tender was heaped a baggage car. Engineer Rafferty was killed; Fireman Dennis Foley and several rail passengers were seriously injured during the crash.

The robbers jumped out of the bushes and fired their guns in the air, terrifying crewmen and passengers. Witnesses said that all but one of the outlaws were dressed in full Ku Klux Klan garb of hoods and robes.

When Foley came to his senses, he found himself lying on the floor of the cab, with the body of the engineer on top of him. Dragging the body onto the track, he began to alert the others on the train, but the robbers forced him to turn back. Extinguishing the furnace fire, he let out the water from the boiler, thus preventing an explosion. The outlaws fired several shots at him inside the train—they missed, sending two bullets through Conductor William Smith’s clothing.

Two outlaws then climbed into the express car with cocked .44s; one—probably Jesse—removed his mask. A rail employee said he appeared to be dressed like a laborer with a “vicious countenance” and did nearly all of the talking. The gunmen quickly forced a guard, John P. Burgess, to open the safe. The startled outlaws discovered it held only $2,000 in currency—and gold was not there for the taking. At the last moment, the gold shipment had been transferred to a later train!

Brakeman Levi Clay had leaped from the rear car when the train crashed and hastened to the nearby town of Anita on foot where he spread the alarm. Clay told citizens that the train had been thrown off the track by 50-75 men who were robbing and murdering all of the passengers.

A telegrapher sent word to Des Moines and Omaha. A train loaded with armed men left Council Bluffs for Adair and dropped off small parties of men along the route where saddled horses were waiting. Roadmaster Frank Cox dispatched 40 men in pursuit of the bandits.

Several other posses also went out, including one involving the Lafayette County Vigilance Committee. Picking up the outlaws’ trail, they found a magnificent mare believed to belong to Jesse James.

The Vigilance Committee arrived in Sedalia, Missouri, on August 27, and officers of the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad furnished them with a special train. The Committee left the train at Montrose and took wagons to Johnson City.

But the committee lost the trail and returned to Sedalia, chagrined and hungry and complaining they were covered with chiggers and ticks. The following day, they took a train, disbanded and went home. The James-Younger Gang didn’t get the loot they expected, but they’d still struck another blow for the old Confederacy.

Tide Turns for James Gang

The boys would have three more years of successful train robberies and bank heists, all against Northern interests. Jesse’s hatred of Yankees became almost pathological after Pinkerton agents attacked the family farm in January 1875. His mother lost her right arm in an explosion; his young stepbrother died in the blast. Frank and Jesse weren’t present. But in September 1876, they made their presence known to the residents of Northfield, Minnesota, a town full of former Union soldiers (and financial investments of two ex-Yankee generals). Two citizens were shot down in cold blood. But the gang paid a big price—three dead and the three Younger boys captured.

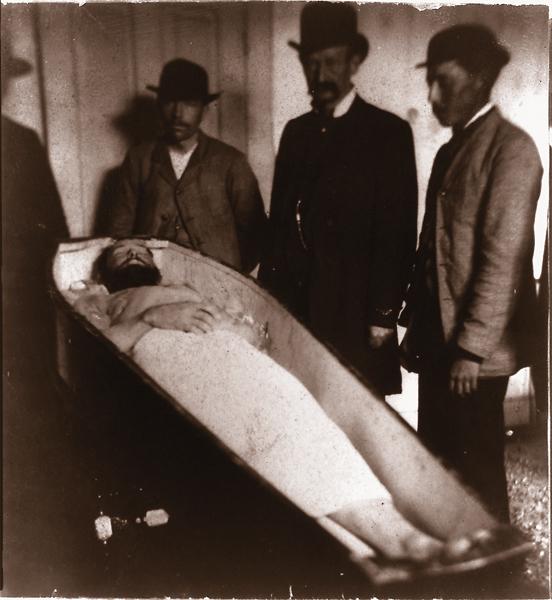

Jesse took a three-year sabbatical before returning to the outlaw trail in 1879. His new gang pulled five more holdups, but the tide had turned. Reconstruction was over. Pro-South Democrats—mostly former Confederates—held the elected offices in Missouri, so the James Gang was no longer needed (or wanted) to fight the Yankees. In fact, they’d become bad for business and commerce. Missouri Gov. Thomas Crittenden knew that and put a price on Frank and Jesse’s heads. The reward convinced Bob and Charlie Ford to gun down their chief on April 3, 1882.

Frank James surrendered a few months later, and in 1883, he was tried for killing a man during the Winston, Missouri, train robbery in 1881. Strangely, Henry Clay Dean—the same guy who had made the speech in Corydon while the gang robbed the bank back in 1871—offered his legal services. The offer was ignored. Perhaps not so coincidentally, Frank was acquitted. His outlaw days were over. He remained a Democrat and proud Rebel for the rest of his life.

John Koblas is the author of Jesse James in Iowa, published by North Star Press of St. Cloud in 2006.

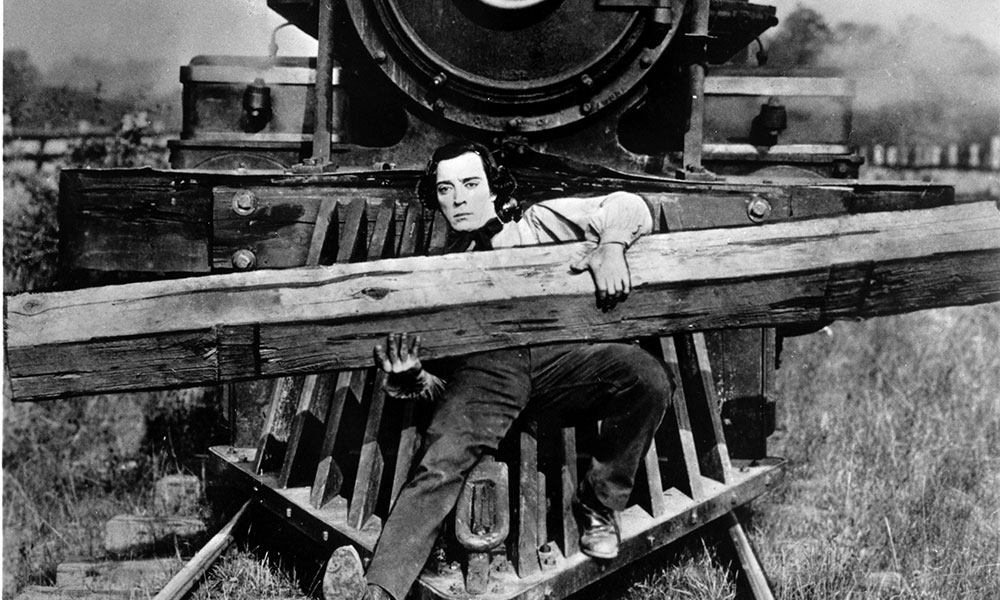

Photo Gallery

– Jesse James courtesy Robert G. McCubbin; all other images True West Archives –