In April 1837, the steamboat St. Peter’s left St. Louis and headed up the Missouri River to deliver supplies to the trading posts of Pratte, Chouteau & Company.

In April 1837, the steamboat St. Peter’s left St. Louis and headed up the Missouri River to deliver supplies to the trading posts of Pratte, Chouteau & Company.

No one had an inkling the voyage would change the history of the Great Plains.

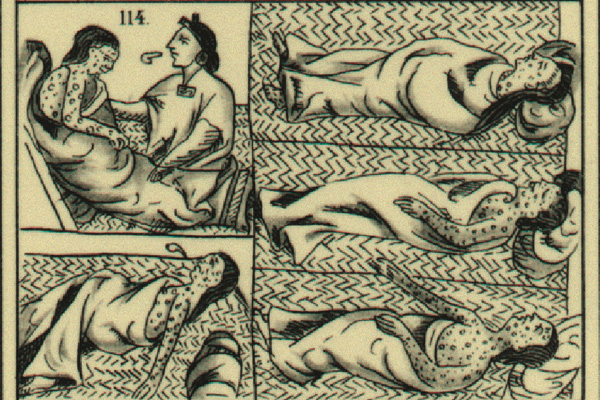

In addition to trade goods, the steamer also carried one of the deadliest pestilences known to man: smallpox. Physicians know it by its scientific name, the virus variola major. The Indians called it “rotting face.”

Unbeknownst to the boat’s captain, Bernard Pratte Jr., a black deckhand became infected with the disease along the lower Missouri. As the St. Peter’s chugged past Fort Leavenworth, in eastern Kansas, the virus spread to other crewmen and passengers. At Fort Bellevue, above the mouth of the Platte River, the steamboat took aboard three Arikara women and their children. The Indians had been visiting the Pawnees and intended to rejoin their tribesmen who had recently moved in with the Mandans at Mitutanka Village near the mouth of the Knife River. Soon after boarding, the Arikaras inhaled the virus, and about 12 days later became deathly ill.

At Fort Kiowa, below the Missouri’s Grand Detour, rotting face spread from the boat’s passengers and crew to the Yankton and Santee Lakotas. Farther upriver at Fort Pierre, across from today’s Pierre, South Dakota, fur trader Jacob Halsey and his pregnant, mixed-blood wife boarded the steamer. An employee of Pratte & Chouteau, Halsey was going to Fort Union, located about three miles above the mouth of the Yellowstone, to become the bourgeois (manager). Within days, smallpox began incubating in the Halseys’ lungs.

When the St. Peter’s reached Fort Clark, which sat beside Mitutanka Village, the Arikara passengers had nearly recovered. One or two of them may have had a few lingering scabs, but the raging fevers, aching muscles, and oozing pustules that had marked the disease’s most deadly stage were gone. As the Arikaras disembarked from the steamboat to join their families, no one suspected that at least one of them was still contagious.

Soon after the St. Peter’s left Fort Clark, the Halseys were bedridden with 106-degree temperatures and a rash that slowly elevated into pus-filled blisters. Unlike his wife, Jacob Halsey had been vaccinated when he was younger, but time had depleted the vac-cination’s effectiveness. As the St. Peter’s neared Fort Union, Mrs. Halsey gave birth to a daughter and died, leaving the child motherless.

At Fort Union, the prostrate Halsey was put to bed in his new quarters. Waiting at the post was Alexander Harvey, who had come downriver from Pratte & Chouteau’s most distant trading house, Fort McKenzie, to pick up supplies. Located in western Montana, the fort served the powerful Blackfeet.

While the steamer returned to St. Louis, Harvey and his crew took their keelboat-load of stores up the Missouri. Accompanying them was a Blackfoot passenger, who had boarded the St. Peter’s after the Halseys had taken sick. Before long, the Indian came down with smallpox and infected some of Harvey’s voyageurs. Shortly after the keelboat reached Fort McKenzie, variola major began raging through the Blackfeet.

Back at Fort Union, clerk Charles Larpenteur decided to vaccinate the Indian wives of the fort personnel. Having no cowpox, the ingredient used for vaccinations, Larpenteur scraped pus from Halsey’s oozing sores and rubbed it into small incisions made in the Indian women’s arms. The result was catastrophic.

That summer and fall, rotting face consumed the Indians of the Great Plains. Like a September grass fire, the virus raced from one Indian band to another until the prairie was littered with their dead.

Among the Hidatsas, Arikaras, Assiniboines, and Blackfeet the disease killed at least half. More tragically, the Mandans were all but destroyed. Like its neighbors, the Lakota Confederation lost many members, but its population was so large, the power of the Lakotas remained intact. Over the coming years, the Lakotas would migrate into the country left empty by their decimated rivals, setting the stage for the Indian wars of the 1860s and ’70s.

The smallpox epidemic of 1837-38 killed an estimated 20,000 Native Americans. Although later flare-ups also exacted a toll, the outbreak introduced by the St. Peter’s was the last major smallpox epidemic in North America.

Myths & Pseudo-Cures

Although there is no cure for smallpox other than the human immune system, throughout history physicians have tried to cure it in novel ways. Some bled their patients, whereas others recommended drinking potions of animal dung. Fort Union clerk Edwin Denig administered purgatives to induce diarrhea.

Most stories about whites giving Indians smallpox-laced blankets are false. Military leaders, such as British general Jeffery Amherst, may have wanted to infect their native foes, but the ability to do so was usually lacking.

A deliberate infection did occur, however, during the 1763 siege of Fort Pitt. French Commander Simeon Ecuyer had two blankets and a kerchief laced with smallpox spores at the fort hospital, and then gave them to the besieging Delawares, causing an epidemic.

R.G. Robertson is the author of Rotting Face: Smallpox and the American Indian published by Caxton Press released in October 2001.

Rotting Face is available at local bookstores or may be ordered directly from Caxton Press at 800-657-6465