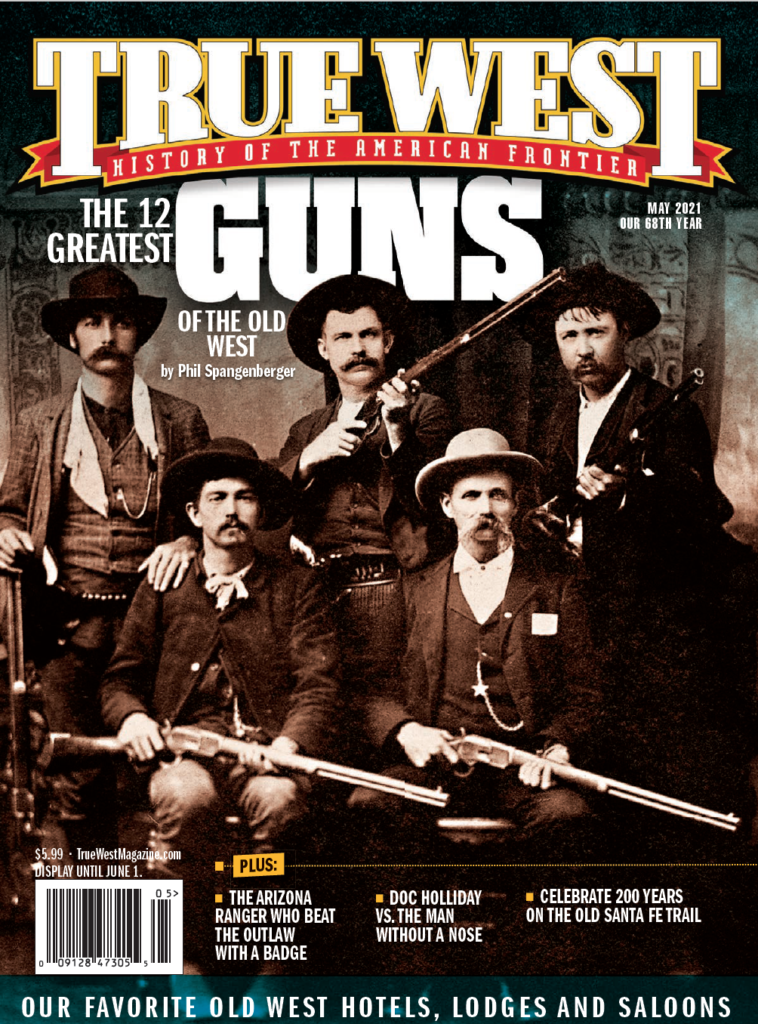

The bicentennial of the National Historic Trail is a great reason to hit the road and rediscover why it is the West’s original “Mother Road.”

When you get right down to it, almost every trail ever blazed was for profit. Despite all the glory associated with them, the lure of money was behind the Chisholm Trail (first for trade goods, then for selling longhorns in Kansas)and the California and Klondike trails (to find goldfields) and the like. The Santa Fe Trail, on the other hand, never even thought about fame—it was all about money.

Says James A. Crutchfield, the Owen Wister Award-recipient for lifetime contributions and author of On the Santa Fe Trail: “Probably the most important legacy of the Santa Fe Trail is its role as the oldest overland trail in the Trans-Mississippi West. In contrast with other extended trails which primarily served as roads of emigration—the Oregon and California trails, for example—the Santa Fe Trail was first and foremost a highway of commerce.”

– Courtesy Gates Frontiers Fund Colorado Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress –

West From Franklin, Missouri

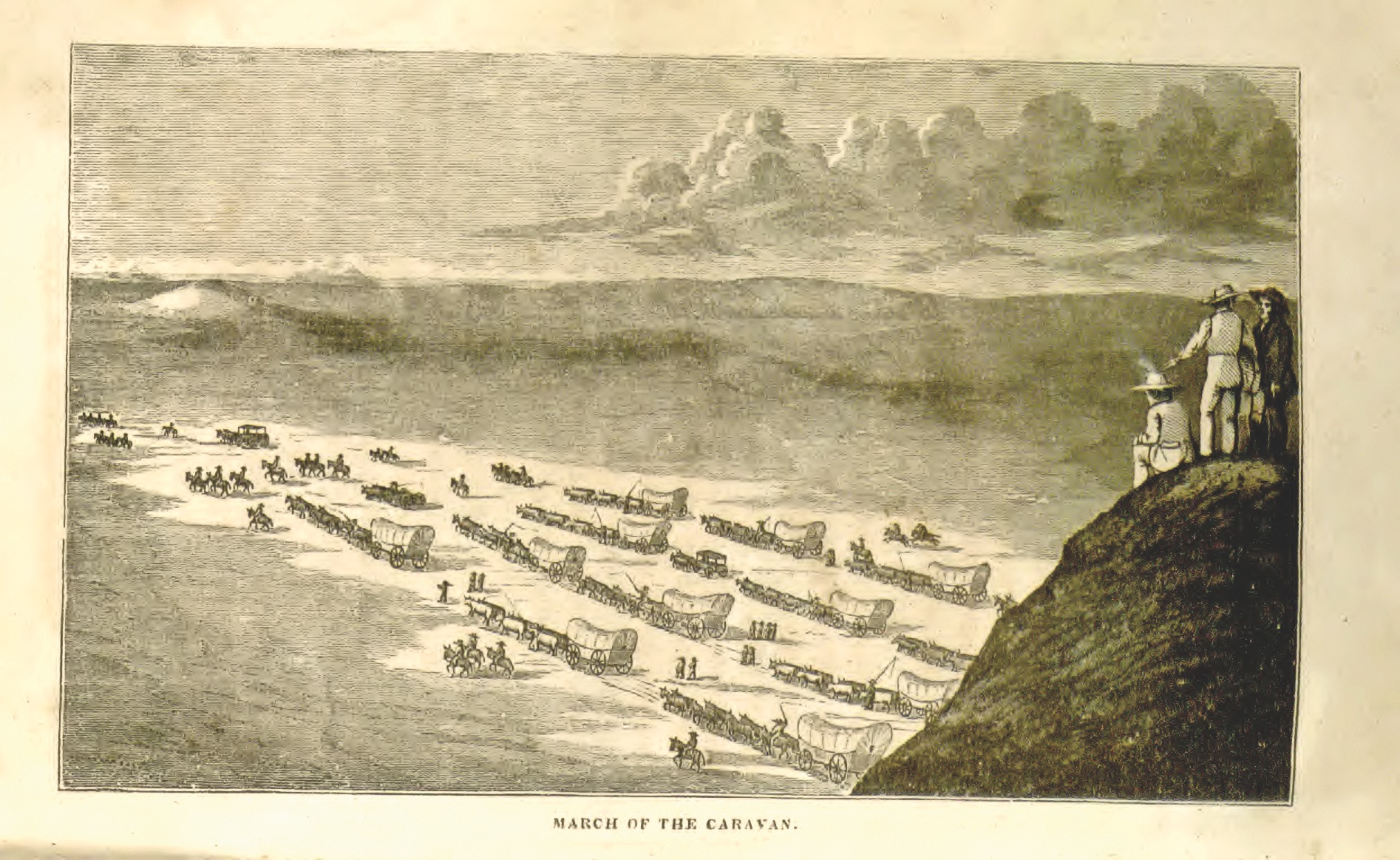

That commerce began 200 years ago, when William Becknell pulled out of Franklin, Missouri, in September 1821, bound for New Mexico. In a notice published in the Missouri Intelligencer, Becknell said he was forming a party to travel “westward, for the purposed of trading for horses and mules and catching wild animals of every description.” It wasn’t exactly a wise business decision, but more of a giant gamble (or at least a crazy leap of faith). Mexico had been under Spanish rule, and the Spaniards had closed the border to any trade with Americans. But with Mexico having declared its independence, Becknell’s party headed west—through Indian country and the parched Great Plains and rugged Southwest. When they reached New Mexico, they weren’t imprisoned, but welcomed. It proved a profitable venture; Becknell made a 200 percent profit.

The Santa Fe Trail was off and running.

“Few stories in westward expansion eclipse that of the Santa Fe Trail in terms of pure adventure or in the profound impact on the growth of the nation,” says Deb Goodrich, chair of Santa Fe Trail 200 and Garvey Texas Historian in Residence at Fort Wallace Museum in Wallace, Kansas.

“The 1,200-mile trek—when the mileage from all the routes is counted—saw commerce and conflict, conquest and subjugation. It saw fortunes made and lost, lives buoyed and busted. What had been a highway between nations became the lifeline of an ever-expanding United States.”

The National Historic Trail

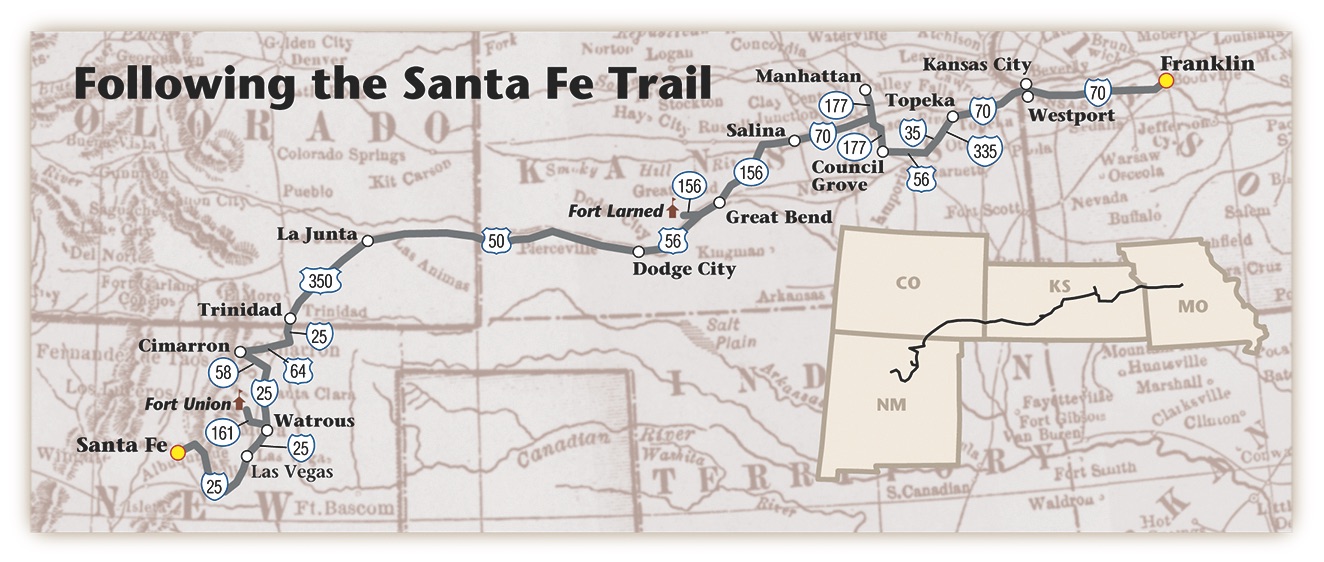

Those 1,200 miles connect five states—Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, New Mexico—and the trail was designated a National Historic Trail under the National Park Service in 1987. Today, there are 900 historic trail sites.

Becknell’s journey began in Franklin, which was washed away by the Missouri River, but the jumping-off place can be viewed from the other side of the river at Boonville. New Franklin replaced Old Franklin in 1828, and monuments can be found on the town’s main square.

With pack mules loaded with trade goods, Becknell and his party followed the wagon road established in 1816 to the ferry at Arrow Rock (Arrow Rock State Historic Site), then took the Osage Trace through Lexington (Battle of Lexington State Historic Site), where James and Robert Aull started outfitting traders bound west in 1822. Due west lies Sibley, where the reconstructed Fort Osage National Historic Landmark illustrates what had been the westernmost Army outpost and a profitable fur factory. It wasn’t on the Santa Fe Trail, Crutchfield points out, but that’s where the government survey of the Santa Fe Trail started in 1825.

– True West Archives –

Independence, Missouri

More important in Missouri was Independence (Independence Courthouse Square, Woodlawn Cemetery), which took over for Franklin as the primary departing point for merchants and also marked the beginning of the Oregon Trail. Westport Landing, now part of metropolitan Kansas City, eventually replaced Independence as what Crutchfield calls “the last ‘official’ beginning for the Santa Fe Trail.” Kansas City has absorbed much of the trail, though the camping site at Archibald Rice farm is now part of the circa-1844 Rice-Tremonti Home in Raytown.

Wide Spot in the Road – National Frontier Trails Museum and Library

Missouri was the jumping-off point for more trails than the one to Santa Fe, New Mexico. And the National Frontier Trails Museum (CI.Independence.mo.us) covers the Santa Fe and more, from Lewis and Clark to the Pony Express to the transcontinental railroads—but the focus shines on the Santa Fe, California and Oregon trails. The Independence museum also houses a library named after Merrill J. Mattes (1910-1996), co-founder of the Oregon-California Trails Association, that includes more than 2,600 first-person narratives.

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Good Grub

A Little BBQ Joint, Independence

Good Lodging

Inn at 425, Kansas City

Kansas

The trail entered Kansas, and many merchants stopped in what is now Fairway to take advantage of the facilities (a blacksmith shop) at the Shawnee Indian Mission, now a state historic site. Near present-day Gardner, the Santa Fe Trail kept west, and the Oregon Trail turned northwest.

Ruts can still be seen east of Baldwin City on a self-guided tour at the Robert H. Pearson 1890 Farmstead Home. On June 2, 1856, those ruts came in handy during the Battle of Black Jack. Members of John Brown’s Free State militia and Henry Clay Pate’s pro-slavery forces looking to avenge the Pottawatomie Massacre of May 24-25 fought for three hours, and both parties used the ruts for cover. “There are new walkways at the site and signs to interpret the events that occurred here,” Goodrich says. “I never visit without feeling the energy, the very spirits of those who clashed here.”

Just west lay The Narrows, a ridge wagons used to avoid draws often filled with mud and rough terrain. Blue Mound, alias Wakarusa Buttes, roughly three miles south of Lawrence, served as a landmark for merchants and wayfarers, and then came a series of crossings: Switzler Creek and Dragoon Creek near Burlingame, and Soldier Creek about 1.5 miles west. Near Soldier Creek on Kansas Highway 31 is the grave of Pvt. Samuel Hunt, a Dragoon serving with Col. Henry Dodge who died in 1835 while returning to Fort Leavenworth with Dodge’s Rocky Mountain expedition.

– Johnny D. Boggs –

After around 10 days of traveling from Westport/Independence, the traders would stop at Council Grove, which offered more than just a respite at the Last Chance Store and today is a must-stop for Santa Fe Trail afficionados for the Post Office Oak, Council Oak, Last Chance Store, Kaw Indian Mission and Hays House Restaurant. In 1825, Kaw Indians signed a treaty that allowed traders safe passage as they journeyed to or from Santa Fe. But the Kaws paid a price. Says Goodrich:

– Trinidad Museum Photo Courtesy Gates Frontiers Fund Colorado Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress/Photo of Raton Pass courtesy NARA, no. 281_30-n-8550 –

“In 1873, the Kaw Nation was moved from their lands along the Santa Fe Trail and relocated to the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. The very state that took its name from the tribe booted them out to take the lands along the trail. Since then, the Kaws have incrementally come home, purchasing back some of their ancestral lands and holding sacred events on the ground. Reclaiming their homeland is an ongoing process for the Kaw Nation. Theirs is just one such story that played out on the trail and continues to unfold.”

From there the trail continued west—Diamond Spring, Lost Spring, Cottonwood Crossing—and to familiar places for Western buffs like Fort Zarah in Great Bend, Pawnee Rock, Fort Larned (check out the Santa Fe Trail Center in Larned) and Fort Dodge in Dodge City (Boot Hill Museum). West of Dodge at Cimarron, Becknell made an executive decision on his 1822 trek back to Santa Fe.

On this trip, Becknell had brought three wagons, 24 oxen and 21 men, but he thought that wagons would not be able to get through Raton Pass on the Colorado-New Mexico border (it’s not always easy in a car today).

Wide Spot in the Road – Sandsage Bison Range and Wildlife Area

Finding a bison range in Kansas shouldn’t come as a surprise—but a national forest? Both can be found at the 3,760-acre Sandsage Bison Range and Wildlife Area (KSOutdoors.com) near Garden City. The forest began in 1905, when the 30,000-acre Garden City Forest Reserve was established on a trial basis, then grew by almost 275,000 acres in 1908. Although the project failed, surviving trees can be found today. Bison, however, have endured since being reintroduced in 1924.

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Good Grub

Hays House Restaurant, Council Grove; Central Station Bar & Grill, Dodge City

Good Lodging

The Wolf Hotel, Ellinwood; Sunnyland Bed & Breakfast,

Garden City

The Cutoff

The Cimarron Cutoff followed the Cimarron River southwest, cutting through a portion of the Oklahoma Panhandle (Camp Nichols was founded by Kit Carson in 1865) and into New Mexico at Clayton, where the Rabbit Ears served as a guidepost despite not looking at all like Bugs Bunny.

The cutoff saved 100 miles and 10 days, but it wasn’t easy. Where the land wasn’t dry, it was filled with quicksand. Indians, including the Jicarilla Apaches, Comanches and Kiowas, weren’t pleased with white men traveling through their country. Near Point of Rocks, between Clayton and Springer, Jicarillas ambushed a caravan in 1849, killing most of the party, and kidnapped Ann White, her infant daughter and her servant. Kit Carson served as a scout for an Army patrol, and tracked down the party, but White was killed, the Jicarillas escaped, and the infant and servant were never found.

Wide Spot in the Road – Cimarron Heritage Center Museum

“Hope died the first time people laid eyes on Boise City, Oklahoma,” Timothy Eagan wrote in The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. “It was founded on a fraud.” But today, the Oklahoma Panhandle town that took a beating during the Dust Bowl is home to the Cimarron Heritage Center Museum, which covers everything from dinosaurs to the Dust Bowl and includes restored buildings and exhibits on the Santa Fe Trail. And there’s free admission to boot.

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Good Grub

Blue Bonnet Café, Boise City

Good Lodging

Branding Iron Bed & Breakfast,

Boise City

– Johnny D. Boggs –

– Courtesy Cimarron Heritage Center Museum –

Colorado

The Mountain Route en-tered Colorado east of Granada and continued west to Lamar (Big Timbers Museum, Madonna of the Trail), through Las Animas and Bent’s Old Fort near La Junta (Otero Museum). Founded in 1833 by William and Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain, the adobe compound was the only permanent Anglo settlement between Missouri and New Mexico.

The Spanish Peaks near Walsenburg served as another beacon for travelers and south of Trinidad (Trinidad History Museum) came Raton Pass. “After ‘Uncle Dick’ Wootton completed his road improvements across the pass, many travelers who previously preferred the Cimarron Cutoff reverted to using the Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail,” Crutchfield says.

– Johnny D. Boggs –

Wide Spot in the Road – Boggsville

In 1866, Thomas Boggs finally got around to establishing Boggsville, one of the first permanent Anglo settlements in Colorado’s Arkansas River Valley. But Zebulon Pike camped here 60 years earlier, and other travelers, including Kiowas and explorer Jacob Fowler, passed through, too. After Boggs built the settlement, good friend Kit Carson became a neighbor in 1867. Carson was buried in Boggsville beside his wife, Josefa, in 1868, but their remains were reinterred in Taos, New Mexico. Today Boggsville Historic Site (BentCountyHeritage.org) includes the homes of Boggs and John W. Powers.

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Good Grub

Jack & Wanda’s Tasty House, Holly; Copper Kitchen, La Junta

Good Lodging

3rd Street Nest Bed & Breakfast, Lamar; Tarabino Inn, Trinidad

– Historic Santa Fe Plaza Photo Courtesy True West Archives/Modern Santa Fe Plaza Courtesy New Mexico Office of Tourism –

New Mexico

The trail continued through Cimarron (Aztec Mill Museum) and Rayado (Kit Carson Museum), past Fort Union National Monument near Watrous, through Las Vegas and Pecos and finally ending at the plaza in Santa Fe (New Mexico History Museum).

The Santa Fe Trail proved good for business. In 1822, trade hit $15,000. In 1860, it was more than $3.5 million.

“Thus, from a political standpoint, the advent and pursuit of trade along the Santa Fe Trail fared well for both countries,” Crutchfield says, “at least until the beginning of the Mexican-American War.”

– Courtesy NPS.gov –

Wide Spot in the Road – Pecos National Historical Park

The Santa Fe Trail began in 1821, but Pecos National Historical Park (NPS.gov), about 40 minutes southeast of Santa Fe, follows history that started thousands of years earlier. This story begins with ancient Pueblo Indians and moves on to include the Pueblo Revolt of 1680-92, Santa Fe Trail, Mexican-American War and the Civil War—where soon-to-be-Sand-Creek-butcher John Chivington won glory for the Union at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in 1862—and into modern times.

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Good Grub

Charlie’s Spic & Span Bakery & Café, Las Vegas;

The Shed Restaurant, Santa Fe

Good Lodging

The Eklund, Clayton;

Hotel St. Francis, Santa Fe

Johnny D. Boggs’s latest novel is Matthew Johnson, U.S. Marshal.