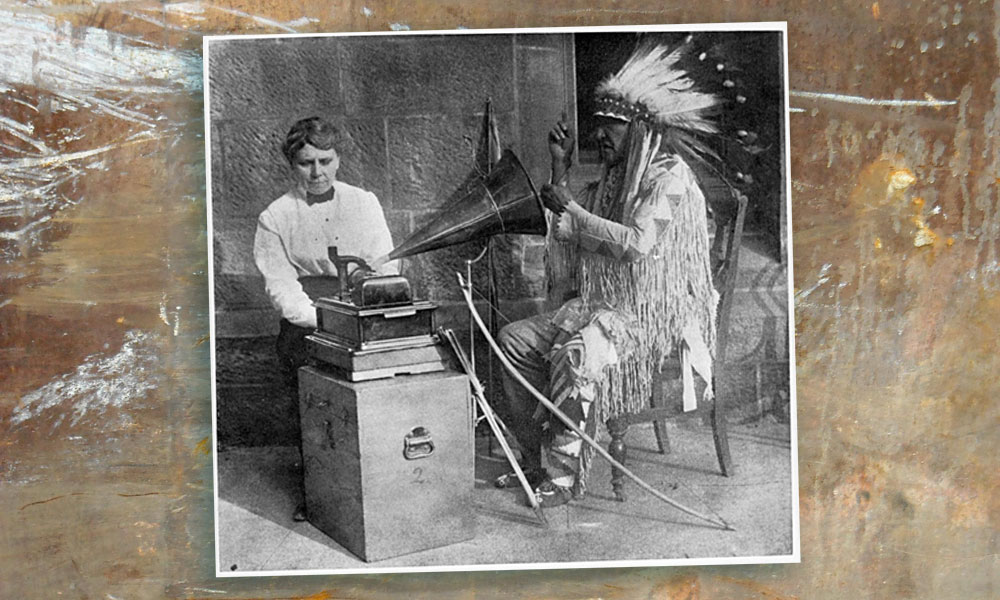

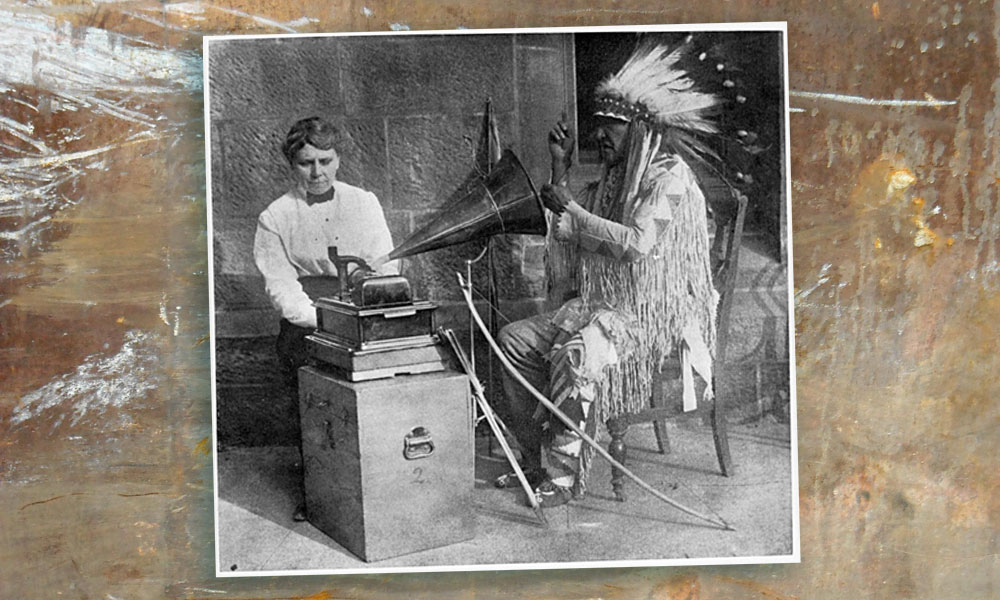

The songs of the Dakota and Chippewa would have been lost forever had it not been for a Minnesota pioneer woman who decided their historical American songs must not be silenced.

Frances Densmore became one of America’s most important ethnomusicologists—saving some of America’s most important native music.

The girl who grew up in Red Wing, hearing Native music from the encampments outside town, long dreamed of preserving the sounds. But she didn’t know how until she discovered Thomas Edison’s lightweight sound recording machine at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. It would be years before she could afford one of the machines. In the meantime, she threw herself into the study of native culture, traveling to North Dakota, Illinois and New York to lecture on what she was learning. By 1903, she added valuable props—an authentic tom tom, birch-bark rattles. Her lectures were popular and broadened interest in the preservation of the music. In 1905 she got a Smithsonian Institution grant of $150 to buy recording equipment, and over the next 50 years, Frances Densmore did more to save Indian songs than anyone else. Her life’s work included 2,500 sounds on wax cylinders from 30 different tribes. She also collected hundreds of Indian musical instruments that are now housed in the Smithsonian.

In 1948, when Frances was 81, the federal government began transferring the songs from wax cylinders to permanent disks in what became the Smithsonian-Densmore Collection of Indian Sound Recordings. She personally supervised the project from her home in Red Wing. By her death in 1957, this remarkable woman had also published more than 20 books and 200 articles on Indian music, customs and culture.