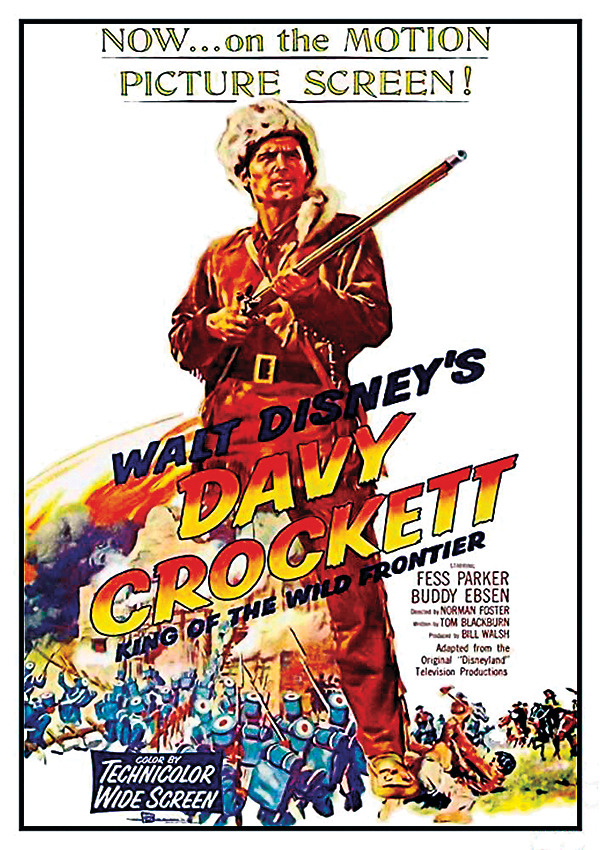

For many baby boomers, the lasting image of the Alamo comes from the ’50s. The 1950s. Fess Parker is the title character in Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier. And the last view we have of him—Davy is on the roof of the church, out of bullets, swinging his rifle “Old Betsy” as a club, bravely (and futilely) holding off the Mexican hordes.

or many baby boomers, the lasting image of the Alamo comes from the ’50s. The 1950s. Fess Parker is the title character in Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier. And the last view we have of him—Davy is on the roof of the church, out of bullets, swinging his rifle “Old Betsy” as a club, bravely (and futilely) holding off the Mexican hordes.

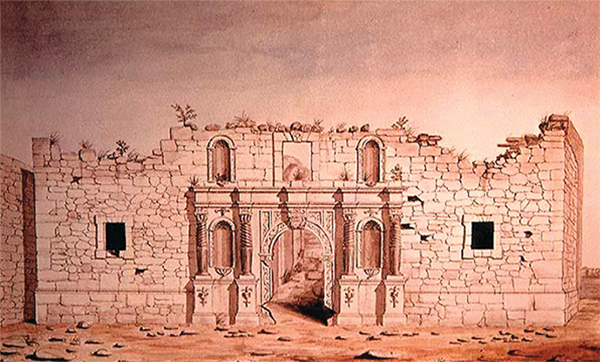

— Courtesy Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin —

Ignore the fact that Davy didn’t die on the roof; there was no roof on the church (and no hump on the façade, either). Davy’s last stand was the symbol of heroism and the fight for freedom. And that church was the Alamo.

Gary Foreman was one of the boomers who saw that show. Like so many, he was enthralled by the story and the place. Little did he know, at the time, that the Alamo would take a central point in his life—that, in a figurative sense, he’d be making his own stand against ignorance and political and bureaucratical quagmires.

It really kicked in nearly 27 years after the Disney program.

A Taxicab Epiphany

“There was one precise moment in time—April 3, 1982—I was photographing the Alamo Church while standing in the street directly in front (it was open to traffic then) and I was almost plowed over by a taxi, forcing me to jump to the curb. When I got up to comprehend what happened, a voice out of nowhere told me, ‘YOU need to do this.’ Hearing that ‘voice’ changed the direction of my life.”

And the direction of the Alamo.

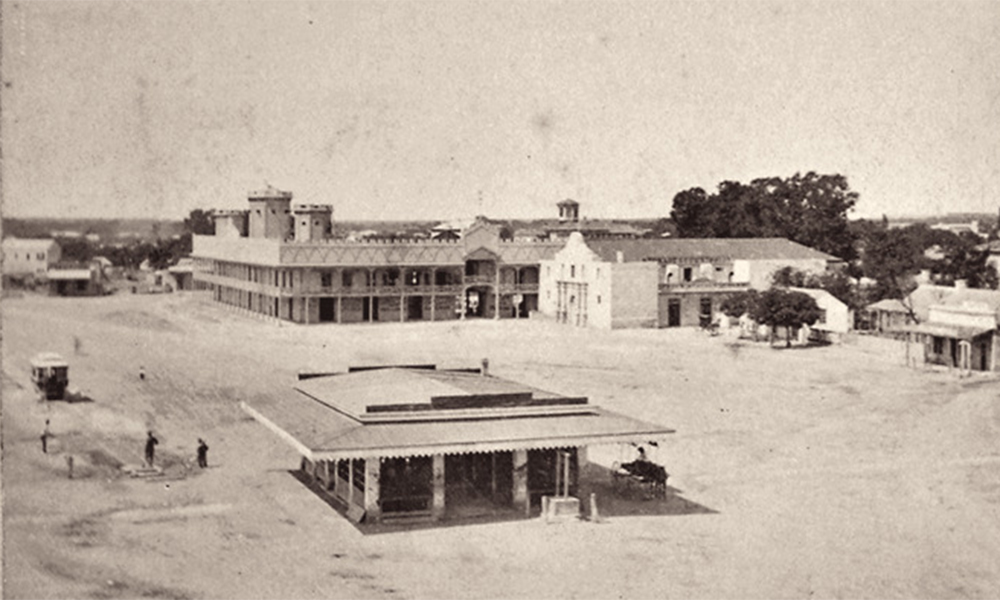

Foreman began serious study of the events and the place, and discovered that the historic mission was more than just the surviving church and the long barracks. The modern Alamo is just one-third of the compound from 1836. The mission had extended dozens of yards in each direction, across now-modern streets and into newer buildings. He was angered that defenders died at spots now occupied by tourist attractions. Ripley’s Believe It or Not! Odditorium, Louis Tussad’s Wax Museum and Guinness World Records Museum stood on Alamo Plaza, directly across from the Shrine of Liberty and Cenotaph Monument.

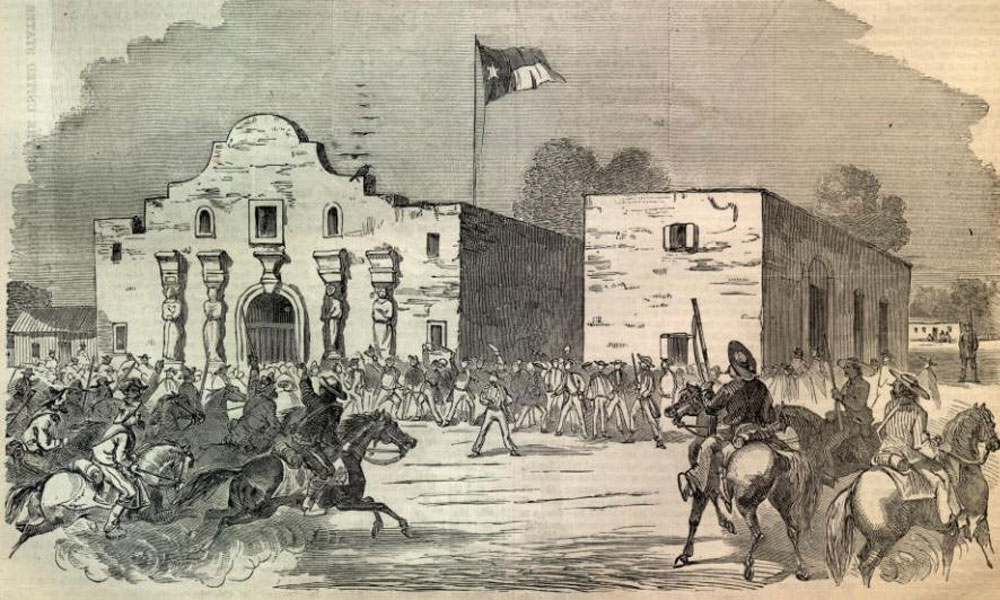

— Images Courtesy True West Archives —

So he began formulating plans and bending ears. This was more than a project; it was a calling, a quest, and “the voice” that had spoken to him wouldn’t shut up.

Foreman’s vision wasn’t exactly welcomed when he presented it in 1984. Peggy Dibrell, chair of the Alamo Committee of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, was dismissive. “Mr. Foreman doesn’t understand that this is a sacred shrine. He wants to turn the Alamo into a tourist trap,” she said. “Besides, Mr. Foreman is not a Texan.”

That’s true. Foreman and his wife are based in the Chicago area. But there were plenty of people—in Texas and beyond—who were (and are) just as concerned about the shrine, not only as a symbol of Texas liberty but also as a monument to men who were willing to sacrifice their lives in the service of freedom. It’s a universal message that attracts around 1.7 million visitors annually from around the world.

— Images of the Alamo from top to bottom courtesy Yale University’s Beinecke Library ca. 1860s, NYPL, ca. 1860s-1870s, NYPL, ca. 1870s-1880s and Yale University’s Beinecke Library, 1885 —

A Voice in the Wilderness

But that universal idea didn’t catch fire, even locally. Gary and Carolyn Foreman—she organized research and other documents and provided a kinder, gentler voice to the campaign—spent most of their time at Native Sun Productions, their documentary film business. As they could, they preached the gospel of the reborn Alamo, using displays, graphics, maps and battlefield tours to get the word out.

And many heard his call, including Fess Parker, the Davy Crockett who first introduced the Alamo to Foreman, and later musician Phil Collins, who, like Foreman, owed his passion for the mission to the Disney series in the 1950s. But hearing is not necessarily acting. Nothing happened for nearly 25 years. At that point, the renewal of the Alamo came front and center.

— Images Courtesy Library of Congress —

So what changed? Why did so many different groups agree to (mostly) put aside their differences and transform the Alamo? No surprise—there’s no agreement on that. Gary Foreman says his 2006 documentary Alamo Plaza: A Star Reborn was the catalyst. Others say it was the state’s 2015 decision to boot the Daughters of the Republic of Texas from its role as caretaker of the Alamo, after more than a century. The DRT was accused of neglecting Alamo maintenance and misusing funds, which the organization denies. Some give credit to Texas Land Commissioner George P. Bush, who staked his political credibility on rebuilding the Alamo. Still others believe it was a decision by state and local governments to cooperate—finally—on plans to preserve and expand the Alamo.

The Project Gains Momentum

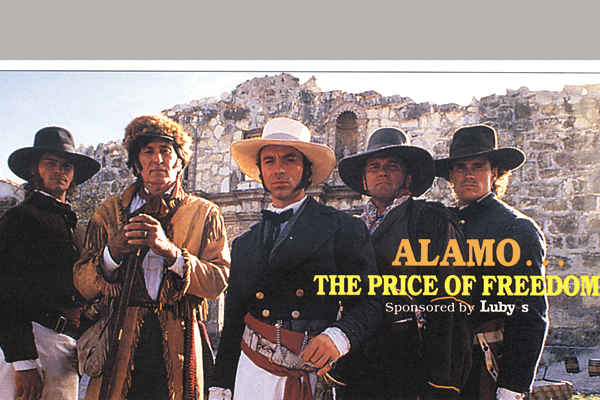

— Courtesy Paul A. Hutton Collection —

Whatever. Over the last four years, various commissions and committees have come up with proposals—several remarkably close to what Gary Foreman put forth years ago (see “The Alamo Master Plan,” p. 20). The city of San Antonio is leasing the historic site from the state of Texas for 50 years, at no cost, with two 25-year extensions after that. And last November, the city council approved a $450-million renovation project. The state will kick in $106 million, the city will provide $38 million, and the rest will come from nonprofits. If all goes as planned, the work will be done in 2024—the 300th anniversary of the Mission San Antonio de Valero, the origins of the Alamo.

Interestingly, Foreman was not included on any of those committees.

— Davy Crockett Image Courtesy Paul A. Hutton Collection/ The Alamo Movie Still Courtesy Batjac Productions —

Make no mistake, most folks know just what he’s done, including Alamo CEO Douglas McDonald: “Gary Foreman has been the persistent visionary who has challenged everyone to understand that the Alamo story is a large historical narrative on a marginalized site. He has inspired, and tormented, others to think larger. The Alamo appreciates his engagement, counsel and passion.”

Yes, McDonald said “tormented.” Others, at least in private, say Foreman has done himself no favors. One Alamo booster says he could be arrogant and abrasive, which turned off many people. And as a result, it was nearly impossible to gain political support for the project.

Other forces took up the banner at that point. And they’ve reached a point where victory is in sight.

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

For his part, Foreman is of two minds. He’s pleased and proud of what he and others have accomplished. At the same time, he can’t relax. He’s still fighting over the possible location of the planned museum and worries that the Alamo could become an urban park, not a true historical site. Those who don’t see things his way? “Tiny provincial minds who are afraid of change, ” he says.

For Gary Foreman, the battle isn’t over. He still stands on the parapets, clubbing the enemy with the long rifle of his passion, determined to win total victory or go down trying. Davy Crockett—or Fess Parker—would understand.

Mark Boardman is the features editor at True West and editor of The Tombstone Epitaph.