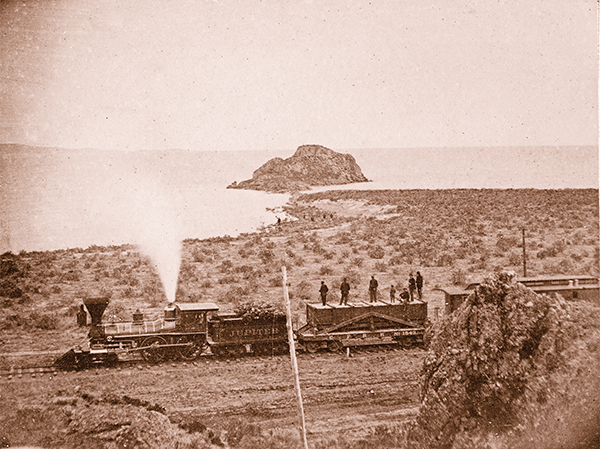

— Courtesy Oakland Museum of California —

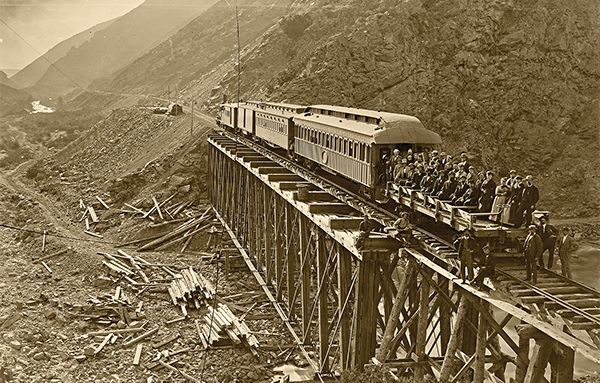

Since the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869, the entrepreneurial “Big Four” rail barons of the Central Pacific Railroad—Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Collis P. Huntington and Mark Hopkins—and Union Pacific Railroad’s financier-leader, Dr. Thomas C. Durant, have been equally lauded and vilified for their actions which led to the completion of the Pacific Railroad from Omaha, Nebraska, to Sacramento, California. Despite all of the critical analysis of the railway bosses, they should also be remembered for recognizing the power of a new medium that had gained prominence during the Civil War: photography. Their independent (albeit competitive) decisions to hire photographers to stoke public opinion and financial support of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific’s construction led to the hiring of a band of few, unheralded photographers—their names mostly forgotten over time—were both visionary and serendipitous.

As a group, photographers Alfred A. Hart, John Carbutt, Andrew J. Russell, Arundel Hull and Charles R. Savage should be remembered for their skill, craft, ingenuity and perseverance. Each of them—carrying their oversized equipment, cameras, chemicals and glass plates—set out along wagon roads, trails and rails between 1865 and 1869 to chronicle the construction of the railways.

Two photographers stand out: Central Pacific’s Alfred A. Hart and Union Pacific’s Andrew J. Russell. Rarely in American history, do we owe so much to so few, as we do to these photographers. Without them and their patrons, our photographic window into the faces of the construction workers and railway crews, the rail camps, dozens of new American boomtowns and the enormity of the engineering, would not exist. We would have been denied our present reflection on the grandness and triumph of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads conjoining at Promontory Summit, Utah Territory, 150 years ago.

Alfred A. Hart

In 1863, the same year the Central Pacific Railroad broke ground, portrait-artist-turned-photographer Alfred A. Hart traveled west from his Cleveland, Ohio, studio to northern California’s gold camps and made his first images of the region. By 1864-’65 San Francisco’s photo studio of Lawrence & Houseworth had photographer Alfred A. Hart under contract. In 1865, the Central Pacific Railroad leaders purchased over 500 photos from L&H, and in 1866 a series of Hart’s photos were released to the New York press. Hart remained the C.P.R.R.’s photographer until the railroad was completed in 1869. In 1870, Hart sold his negatives to fellow photographer Carleton Watkins (who had replaced Hart as the C.P.R.R. photographer), and Watkins published them as the Watkins Pacific Railroad series.

Fortunately, in the intervening 150 years, Hart’s massive body of work has been curated by numerous archives, researched, catalogued and identified, although many of the images he made for Lawrence & Houseworth may never be credited correctly. After his tenure with the Central Pacific, Hart returned to portrait painting and other photographic ventures, splitting his time between San Francisco and New York. He struggled financially most of his life and died in poverty in California in 1908.

The following images represent a cross-section of Alfred Hart’s photography of the Central Pacific Railroad’s construction between 1865 and 1869.

— Courtesy Stanford University Library —

— True West Archives —

— Courtesy Stanford University Library —

— Courtesy Stanford University Library —

— Courtesy Stanford University Library —

Andrew J. Russell

Like his Central Pacific rail baron brethren, Union Pacific financier and director Dr. Thomas C. Durant realized the power of the press and the new medium of photography. In October 1866 he hired photographer John Carbutt to chronicle an executive celebratory Union Pacific train to the end of tracks at the 100th meridian near Cozad, Nebraska. Durant’s release of Carbutt’s images to the New York press inspired and galvanized financial, public and political support of the U.P. Over the next two years, photographers Charles R. Savage and Ridgway Glover followed the U.P. westward, but neither delivered to Durant what he needed for publicity as Hart was producing for the Central Pacific. (Glover was killed by Sioux Indians outside Fort Phil Kearny during the Red Cloud War 1866, while Savage, a Mormon English immigrant, was primarily a photographer in Salt Lake City.)

In early 1868, Durant hired New Yorker Andrew J. Russell, a distinguished Civil War Army photographer, to go west on the

Union Pacific and photograph its progress and construction as it raced the Central Pacific to the finish line in the Utah Territory. After the Golden Spike ceremony, Russell continued his career as a photographer and artist. Little is known of Russell’s life after 1880, and most likely he was impoverished when he died in 1902. He is buried in Brooklyn, New York.

The following images represent a cross-section of Andrew J. Russell’s photography of the Union Pacific Railroad’s construction in 1868 and 1869.

— Courtesy Union Pacific Railroad Museum —

— Courtesy Oakland Museum of California —

— Courtesy Oakland Museum of California —

— Courtesy Oakland Museum of California —