– True West Archives –

“We have marched a long way to meet the enemy and I do not intend to return without meeting them. I had rather die than retreat.” Thus did old frontiersman Zadock Woods cast the deciding vote sending his companions to slaughter.

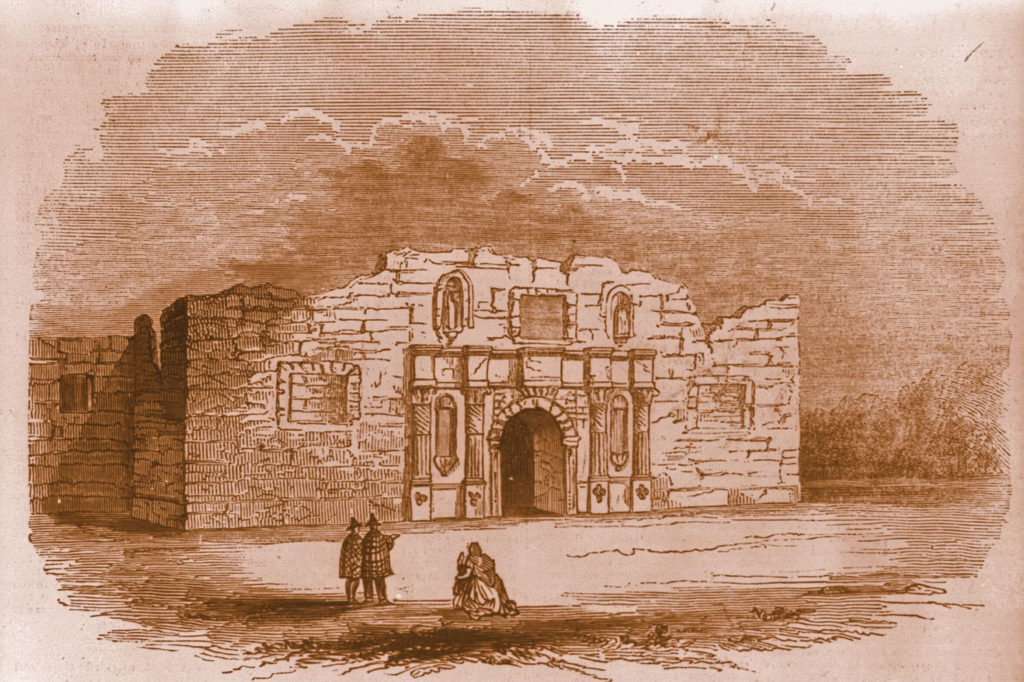

The situation was this: The Mexican Army invaded Texas and captured San Antonio on September 11, 1842. Couriers raced across the settlements drumming up volunteers to drive off the invaders. Zadock and his sons, Norman and Henry Gonzalvo (Gon), answered the call. Snatching up rifles and cornbread, the three rode for San Antonio, joining more volunteers from nearby La Grange along the way.

Two days hard riding later, the 53 volunteers, through a series of missteps and just plain bad luck, found themselves between the Texan and Mexican forces, slugging it out on Salado Creek north of San Antonio. One hundred and fifty Mexican dragoons started galloping in their direction.

Their captain, Nicholas Mosby Dawson, laid out the options: fall back four miles and join up with other reinforcements they had passed earlier in the day or seek shelter in a nearby mesquite motte and fight it out. The older men grumbled at the very thought of retreat and Zadock roared out his own challenge sealing their fate.

– All Images Courtesy Author’s Collection Unless Otherwise Noted –

The dragoons reigned in before the Texans as they took up position behind the trees. A small detachment rode up closer, white flag flapping in the breeze, calling out for parlay. Dawson motioned them away. More dragoons began advancing at a slow trot—until Texan bullets emptied two Mexican saddles. Humors soured. The lancers thundered forward in a blind rage but withering fire from the Texans sent dragoons spinning into the dirt or beating a hasty retreat. Dawson’s company held the upper hand—for the moment.

But jubilation died with the sudden crack of a cannon. Hot metal scalped the mesquite grove. Branches, mulch and canister showered down on scrambling men. None had seen a cannon being positioned during all the shooting. Another shot whistled through the trees. Gon Woods heard men and horses screaming in agony, later remembering: “Their canister and grape made awful havoc among our men. I received a wound in the shoulder early in the action and my two companions, J. B. Alexander and Elam Scallorn, were killed at my side… Death in every shape stalked through our thin ranks.” About a dozen of the Texans and almost all their horses lay dead. Cherokee snipers started picking off survivors. That’s when Gon heard his brother scream.

Norman collapsed in a mass of agony, shot across the hip. Zadock threw himself across his son’s body as another volley of canister sailed overhead. He raised back up to help his son staunch the blood when a sniper’s bullet caught him in the heart. The old man fell dead alongside his writhing son. It was Zadock’s 69th birthday.

– Courtesy The Vinkhuijzen collection of military uniforms, NYPL Digital Collection –

Gon’s cousin and fellow survivor Joseph Robinson grimly recalled the scene: “The fate of our whole company seemed inevitable in death. About two thirds of our number were already among the dead, dying and wounded, and nearly all the horses were killed. Existence was departing for eternity, in the purple streams of life, through many a fatal wound. Among our dead was an aged veteran, Zadock Woods, nearly 80 (70) years of age. By the side of the grey-haired soldier reclined his son Norman, languid with pain and loss of blood, and telling his brother Gonzalvo that it was his fate there to die, and, handing him a pistol, told him to leave him and make his escape if possible. The scene before us and the thoughts it inspired of those whose fathers, husbands and brothers had here fallen, struck up with mingled emotion of horror and compassion.” Even a horrified Mexican officer reportedly declared, “Such men are too brave to die!”

Norman pleaded with his brother to escape and take care of his wife, Jane, and their five children. The brothers embraced one last time. They never saw each other again.

The grapeshot ceased and the Mexicans charged the depleted company. “Then began the work of death in its most horrible forms. Our fire was reserved until within pistol shot distance, when the men clubbed their guns and used their knives. The wounded were massacred like brutes, being fit subjects for Mexican bravery,” Gon remembered bitterly.

Contemporary newspaper reports described his escape: Gon “threw down his gun, advanced some 20 paces toward an officer…and in their own language (which he speaks very well) asked for quarter and told him they would all surrender.” His offer wasn’t accepted. One Mexican fired point-blank but the gun misfired. Two others swung at him with rifle butts, punching his left ear and nearly breaking his arm. Gon darted back into the trees and was shocked to see a Texan horse alive and running loose. It took him only an instant to mount. “Woods! Woods! Don’t take my horse!” John Church of La Grange ran toward him. Gon fought the temptation to ride out anyway, but he alighted and handed Church the reins. He dove into a patch of high grass and wormed on his belly through the prairie till he saw what looked to be a large opening between two groups of infantry—a narrow doorway to freedom. He took a deep breath and sprinted.

Hooves thundered up behind before he made it halfway. He spun around, raising his arms again to surrender to the four dragoons charging him. “The first struck at him with a sword; he squatted and the sword passed over his head. At the next blow the sword struck him on the top of his head and cut him to the skull for about three inches. Another one of the four charged upon him with a lance and thrust it at his heart. Mr. Woods caught the lance with both hands, turned it aside, jerked the Mexican off his horse, and ran the lance through his body. He raised the lance and offered battle to the three remaining Mexicans, determined to sell his life at as dear a price as possible. To his joy and astonishment, they fled…”

Gon made for the dead man’s horse but the beast would have none of it. It kicked and bit till he managed to get aboard. But now the furious beast refused to move faster than a trot. Gon had finally managed to steer the stubborn animal to the edge of the battlefield when a bullet hissed past. He saw four Mexicans running toward him. The horse froze. Gon kicked and cursed it, but it stood there waiting to be caught. He leapt from the horse, still clutching the spear as his only weapon, and ran. Luckily, the soldiers just wanted the horse. They did not follow.

Gon dodged into a thicket and collapsed in a tall bed of grass. He could rest at last. “In the stillness of that beautiful country he thought over the transactions of the last two hours. He thought of his comrades—a few hours since full of courage, life and hope. When he parted with them a few minutes before, most were weltering in their own blood, and the survivors were rapidly falling beneath the murderous blows of a merciless enemy. All was still; and every minute he listened to hear the sound of horses’ feet as his enemies were coming in pursuit. It seemed that night would never come…”

Night finally fell and Gon stumbled off. It took almost a week of running and hiding to make it home and a full two months to recover from his wounds.

Out of Dawson’s company of 53, 15 survived to be taken prisoner. Only two escaped.

Norman was among the survivors, crippled by bullet and sword wounds. He and the others were taken 1,000 miles south to the infamous castle of Perote (The Coffin)—a high-walled prison between Mexico City and Veracruz. The castle would indeed prove a coffin for six of the 15 survivors—including Norman. Still weak from his wounds, he died of typhus December 15, 1843, and was buried in the moat of Perote. Gon made good on his promise to take care of his sister-in-law when he married her a year after Norman’s death. They had three children of their own. One son they named Norman.

Zadock and the others slain were eventually buried in a tomb overlooking the Colorado River at Monument Hill State Park in La Grange alongside the men of the Mier Expedition.

Henry Gonzalvo Woods later became a successful planter, served briefly in the Confederate army and finally met his end on October 17, 1869, shot down in an ambush during the Sutton-Taylor Feud. The lance he took from the Dawson Massacre is on display at the Alamo, and the story of his escape has been passed down for generations by his descendants, enshrining his daring and heroism for generations to come.