Meriwether Lewis and William Clark wrote often of encounters with Ursus horribilis—grizzly bears—as they made their pioneering journey across the Louisiana Purchase during 1804-1806.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark wrote often of encounters with Ursus horribilis—grizzly bears—as they made their pioneering journey across the Louisiana Purchase during 1804-1806.

Mountain Man Hugh Glass had a near-deadly confrontation on the plains of South Dakota, while other explorers and Indians also faced the ferocious bears, far from where we think of them as living today.

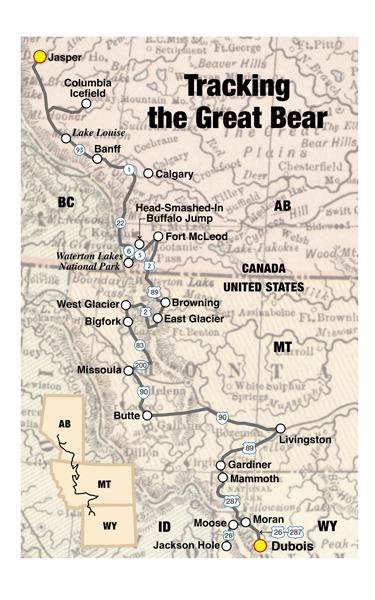

Although in the 19th century, grizzly bears roamed far out onto the plains, the last remaining wild habitat of the grizzly is on the backbone of the continent along the Rocky Mountains from Yellowstone National Park in northwest Wyoming to Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada. It is a region that includes five major parks: Yellowstone and Glacier in the United States, Waterton International Peace Park, Banff and Jasper in Canada, along with many significant historic sites.

Traditionally the land was the territory of the timber wolf and the grizzly, as well as the Sheepeater, Crow, Blackfeet and Salish-Kootenai Indians in the United States, and the Blood and Piegan tribes in Canada.

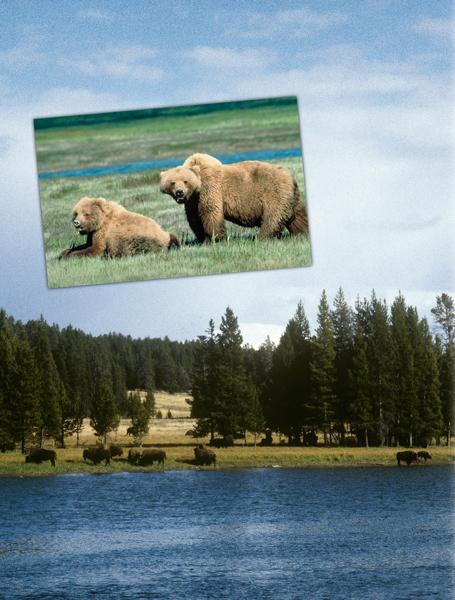

I have seen grizzly bears in the wild only in the Yellowstone area, and then, fortunately, at distances that were safe both for the bears and for me. One viewing occurred east of Mammoth in the Gardner’s Hole area of the park. I was involved in a “Lodging and Learning” program, co-sponsored by Xanterra Parks & Resorts and the Yellowstone Association. We had taken a van to the area in early evening, hoping to see wolves. Instead we saw a grizzly, busily chewing on something dead, possibly an elk; it was impossible from our vantage point to see the carcass even though we had powerful spotting scopes.

The most amazing part of that wildlife watching experience occurred when three large bull buffalo lumbered through the crowd that had gathered beside the road. The bulls never shifted their pace as they approached the grizzly’s location. One of the Yellowstone Institute biologists told me the buffalo would veer off when they actually spotted the bear; the bear being the dominant creature in Yellowstone. The bulls’ massive heads swung routinely from side to side as the bison marched ever closer to the grizzly, who finally paused in chewing on the carcass, threw up her nose and then turned tail and ran, very quickly, away. She first headed straight for our position—and the naturalists told everyone to climb in vehicles to avoid any bear-human contact—but when she was still a few hundred yards away, she veered up a hillside where she disappeared into the timber.

The bear’s reaction wasn’t what the biologist expected. He told our group that he believed a buffalo must have once closely confronted her, making her cautious on the approach of these three big bulls.

We later drove back toward Mammoth and came upon another “bear jam” on the highway, where we got an incredible view of the same bear. She had moved into the forest then out onto a hillside where she was stretched out with her head and paws on a rock. A man who arrived there before us had his spotting scope set up, and he invited everyone to take a look through it.

Because she was above us on a cliff-like hillside, she was closer than our earlier view, but we were no threat to the sow, and we felt none from her. The powerful scope drew her in, so the view was just of her massive head. She seemed to be looking right at me when I had my turn at the scope; I could even see individual hairs on her face.

The exhilaration of seeing that bear twice, her encounter with the buffalo and the peaceful stance she displayed on the cliff are all cherished moments in some of North America’s most spectacular country.

Not everyone who tours along the great bear’s corridor will see a grizzly bear or hear a timber wolf howl, but you can become more aware of the land those creatures depend upon. In becoming more aware, you will nurture your own spirit. As one resident of the area told me, this is a place to “power up your soul,” whether it’s by walking through a dripping rainforest environment on Trail of the Cedars near East Glacier in Glacier National Park in the U.S. or standing on a thousand feet of glacial ice at the Athabasca Glacier in Jasper National Park in Canada.

Entering Wyoming’s Grizzly Habitat

Travel with me as we follow the tracks of the great bear. The route extends over roughly 2,200 miles of the wild Rockies along the Continental Divide.

We begin in Dubois, Wyoming, which is on the southern end of the grizzly’s habitat these days. This small town is most known for its impressive herd of Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep that roam up into the Wyoming range during the summer and spend winters on Whiskey Mountain just south of town. Some grizzly bears have migrated this far south, but they aren’t as common here as in the mountains to the north. While in Dubois, you should visit the National Bighorn Sheep Interpretive Center; during winter, the center conducts tours to the sheep winter range for close-up views of the wild sheep. Next door is the Wind River Historical Center, which exhibits displays of local history.

From Dubois, travel northwest on U.S. 287/26, which takes you across Togwatee Pass (currently, there is some road construction in this area) and gives you grand views of the Grand Teton mountain range before you drop into Jackson Hole. You can remain on U.S. 287 at Moran and continue directly north into Yellowstone, or you can follow U.S 26 south into Grand Teton National Park for unobstructed views of the Grand Teton range. At Moose Junction, turn west onto Teton Park Road, toward the Moose Visitor’s Center and a main entrance station to Grand Teton National Park. You can then follow the park road near the base of the Tetons back north to Jackson Lake Junction, where you will again connect with U.S. 287, taking you into Yellowstone National Park.

Within Yellowstone, the first national park in the United States, the roads are patterned like a figure eight with visitor services at several main junctions, including Fishing Bridge (a site where grizzly bears are often spotted because they like to do their own fishing), Grant, Old Faithful, Canyon and Mammoth. You’ll almost always see buffalo in the Hayden Valley, have an opportunity to view elk near and north of Old Faithful, and may encounter grizzly bears as you cross Dunraven Pass and in Gardner’s Hole west of Mammoth. Wolves roam throughout the park, but they are most often spotted in the Lamar Valley, in the park’s northeastern corner, where they were released back into the wild in 1995.

Yellowstone’s geyser basins around Old Faithful and at Norris are ever-changing displays of thermal features. You will want to spend at least a couple of days in Yellowstone to really experience the park’s diverse landscape and wildlife. Soak in the warmth generated by thermal features, because later on, you will need it.

On Top of the World

From Mammoth, travel north through Montana’s Paradise Valley to Livingston on U.S. 89. Then travel west on Interstate 90 to Butte until you reach Missoula. From there, take Highway 200 east and then Highway 83 north to Bigfork before following Montana Highway 206 to West Glacier National Park.

U.S. 2 circumnavigates the western, southern and eastern sides of Glacier, but to view its interior, you must drive Going-to-the-Sun Road, which is not for flatlanders. The road is under construction, but Glacier has implemented a free shuttle service and transit stops for it are clearly marked along the Going-to-the-Sun Road. The shuttle system offers a travel option for visitors to avoid traffic and parking problems associated with rehabilitation of the Going-to-the-Sun Road, and offers an alternative to driving for park users. The transit system will provide two-way service along Going-to-the-Sun Road between the Apgar Transit Center and St. Mary Visitor Center.

The highway corkscrews into and across the Rockies. At the summit is Logan Pass Center, and I highly recommend that you take a hike onto alpine tundra, where snowbanks can and do remain on the trail well into mid-summer (remember what I said about soaking in thermal warmth in Yellowstone). You will probably see mountain goats grazing the alpine forage and almost certainly will have spectacular views from a place that seems to be on top of the world.

On the eastern side of Glacier, hike around or take a boat ride onto Swift Current Lake. I also encourage you to drive southwest to Browning, where you can immerse yourself in Blackfeet culture, which is casually explained if you take a tour with Curly Bear Wagner. One of the most recognized members of the tribe, he has worked untiringly to share his Blackfeet culture with visitors to the region and to preserve important sites such as the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump located in Alberta, Canada. Another good place to learn about Blackfeet culture is to stay at Darrell Norman’s Tipi Village just outside of Browning. I spent a night there one September. Darrell fed me fish for dinner before I headed to one of his lodges, where my bed was a modern mattress covered with buffalo robes. The wind was coursing down the eastern slope of the Rockies and sweeping across the plains. When it hit the lodge, it circled around both inside and outside, stirring the embers in the small fire that warmed the lodge and causing sparks to dance and fly.

Canada’s Triple Divide

From Browning, head north into Canada so you can learn more about the Blackfoot Confederacy, which involves the Piegan and Blood tribes. Follow U.S. 89 north, which turns into Provincial Highway 2 in Canada.

Conflicts between early settlers and members of the Blackfoot Confederacy left the region that is now Alberta, Canada, extremely unstable in the early 1860s-70s, leading to the establishment of the North West Mounted Police. Their commander, Col. James MacLeod, sought assistance at Fort Benton in the Montana Territory. His troops continued along the Whoop-up Trail, first to Fort Whoop-up and later to a new site on the Oldman River, which became Fort MacLeod, a town where you will still see original buildings from the NWMP and the official North West Mounted Police Museum.

To the west is Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, a World Heritage Cultural site that is one of the largest, best preserved aboriginal hunting sites in North America.

From Fort McLeod, turn back toward the southwest, taking Provincial Highway 2 toward the south and Highway 5 toward the west to Waterton Lakes National Park. Enjoy high tea at the Prince of Wales Hotel and take a boat ride across Waterton Lake to Goat Haunt, where you will find a series of trails—both long and short—that give you access to the Glacier Park backcountry.

After an interlude in Waterton, travel north again on Provincial Highways 6 and 22, skirting just west of Calgary. Follow Canadian Route 1 west into Banff National Park and the community of Banff, which is situated deep in the heart of the Canadian Rockies.

From Banff, drive north along the Icefields Parkway, Highway 93, through Banff National Park and into the southern portion of Jasper National Park. The destination: Columbia Icefield. The Dome, Stutfield and Athabasca Glaciers are visible along the route that also passes the beautiful Lake Louise.

At the icefield, I explore the Columbia Icefield Centre before boarding a huge (and I mean huge) vehicle for a tour onto the Columbia Icefield and the Athabasca Glacier. This is one of the most incredible places I have ever stood: on a sheet of ice formed centuries ago. The glacier ebbs and flows, is the largest sub-polar sheet of ice in North America (covering 130 square miles) and is packed to a depth of 1,200 feet. This area also represents one of two triple divides in the world (the other is in Siberia) because from the hydrological apex of the Athabasca Glacier water flows to three oceans—the Atlantic via Hudson’s Bay, the Pacific via the Columbia River and the Arctic. Standing on the glacier with dozens of tourists from Japan, Canada and the United States is surreal, but, at the same time, it’s possible to imagine how the world looked during the last Ice Age. Great power can be found in this World Heritage site, just by knowing such places still exist.

The Canadian Rockies are still a habitat for grizzly bears and timber wolves. The region (including Banff and Jasper National Parks) offers some of the most spectacular scenery on the continent with its sharply jagged mountain peaks, glacial remnants of the Little Ice Age and pristine lakes and rivers that appear turquoise from the glacial sedimentation. The Columbia Icefield and Banff’s Cave and Basin mineral springs attract millions of visitors, and yet manage to give each a sense of wonder at how nature restores itself and an individual’s spirit.

The managers responsible for preserving and caring for the land and its resources all along the Great Bear’s Trail have a daunting task. They must weigh and balance issues—such as reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone, or delisting of grizzly bears from the Endangered Species Act—with the impacts to recreationists and agricultural producers.

Though extinct in much of its historic range—such as the plains of eastern Montana—the grizzly bear continues to roam free in the wildlands of this corridor along the North American backbone. It is a symbol of all that is right in the ecosystem, and one that can be tracked to determine how development is affecting both the bear and the land.

Photo Gallery

– Grizzlies by Chris Servheen/U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service; All images by Candy Moulton Unless otherwise noted –