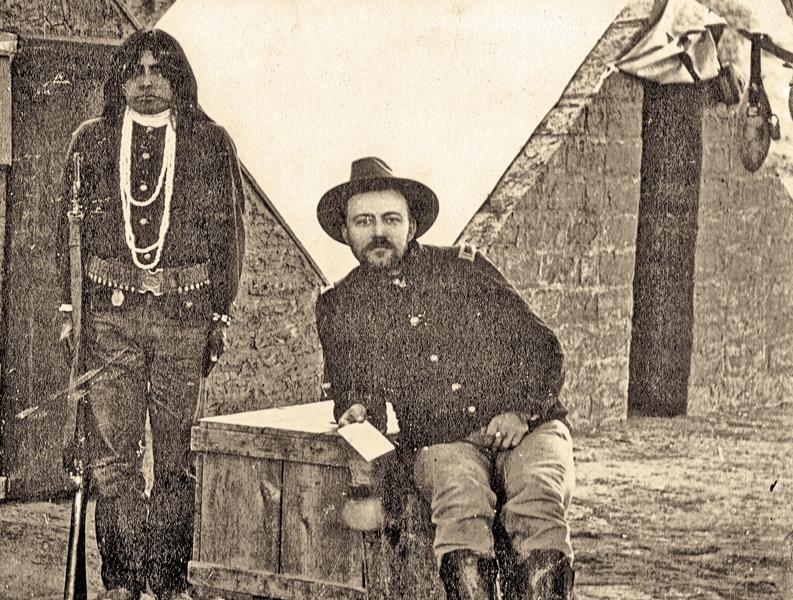

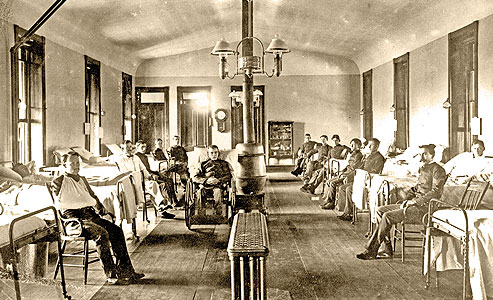

“There was one class of officers who were entitled to all the praise they received and much more besides, and that class was the surgeons, who never flagged in their attentions to sick and wounded, whether soldier or officer, American, Mexican, or Apache captive, by night or by day,” wrote John Bourke, in On the Border with Crook.

“There was one class of officers who were entitled to all the praise they received and much more besides, and that class was the surgeons, who never flagged in their attentions to sick and wounded, whether soldier or officer, American, Mexican, or Apache captive, by night or by day,” wrote John Bourke, in On the Border with Crook.

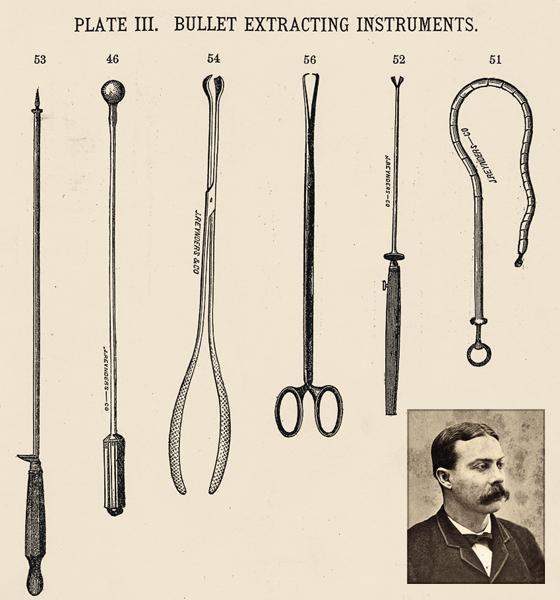

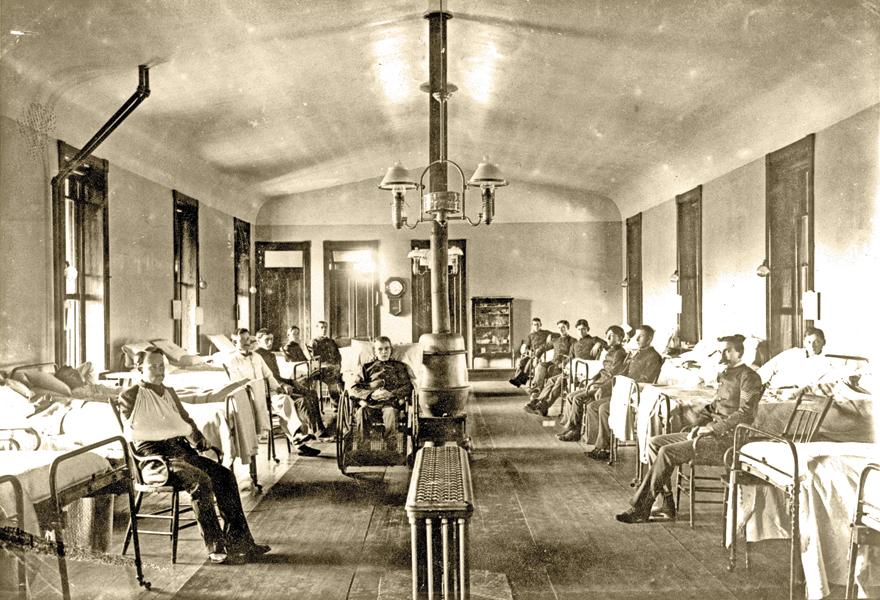

For the frontier soldier serving in the Southwest, a point often came when luck ran out and an arrow or a lead slug felled him, or a mosquito sting brought him low with malaria. Likewise, other diseases, acquired innocently at times, or as a result of sprees on Whiskey Row or in the cribs at hog ranches, lurked. Fortunately, these casualties of human and macrobiotic enemies had an ally—military doctors.

In fact, the arrival of the U.S. Army into the territory we know today as Arizona brought some of the first medical men to the region. As early as the Mexican-American War that waged from 1846 to 1848, physicians accompanied Stephen Watts Kearny’s Army of the West, and the Mormon Battalion that followed, on marches to conquer California.

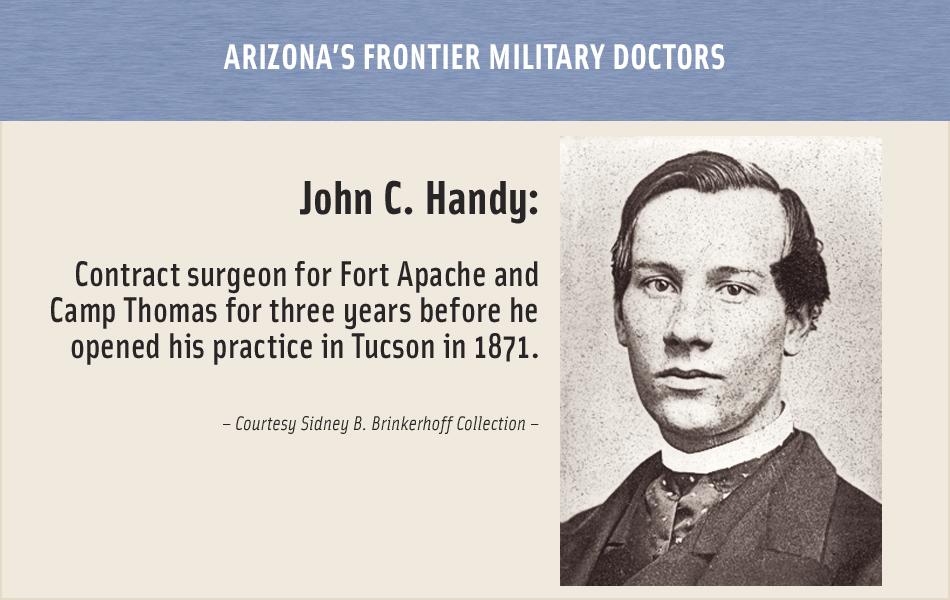

More than a dozen years later, Arizona became a territory. A call went out for contract surgeons—men of medicine hired to undertake all garrison and field duties. In exchange, they held the rank of acting assistant surgeon (equivalent to acting first lieutenant), but they were not authorized to wear the uniform. They received a base pay of $1,600 a year, not a princely sum considering a successful sales clerk in New York City might earn $1,200 a year.

Candidates arriving from the East were somehow willing to practice in what must have seemed like a sweltering Siberia. Their number included Dr. Charles Leib, who dabbled in politics in Prescott, then the territorial capital. He also penned a colorful memoir of his American Civil War activities, with the provocative, timeless title, The Chances for Making a Million.

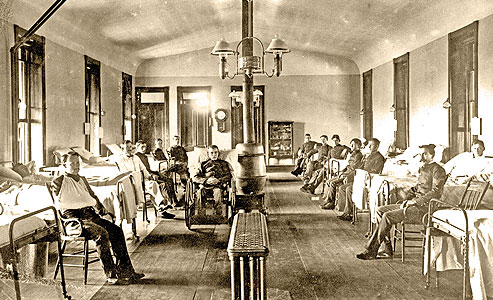

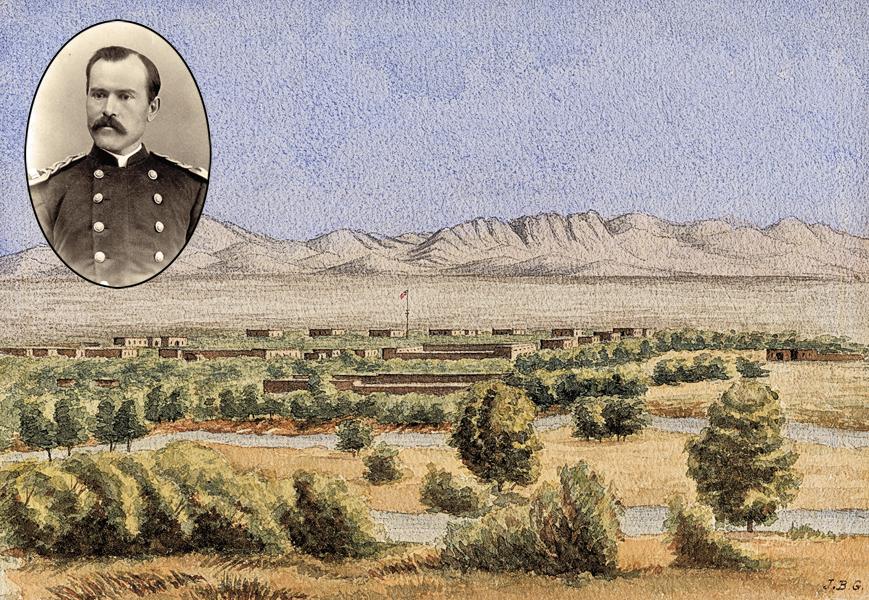

Medical Corps assistant surgeons received the same salary as their contract colleagues, but the amount rose according to the length of military service. Both classes drew the same benefits. Army regulations authorized the lowest ranking medicos a billet with a multipurpose living space of approximately 15 feet by 15 feet and a kitchen. Captains were provided with larger spaces, such as two rooms and a kitchen, and so on, as one moved up the military ladder. No provision was made for the number of members in the household. Consequently, rank had its privilege.

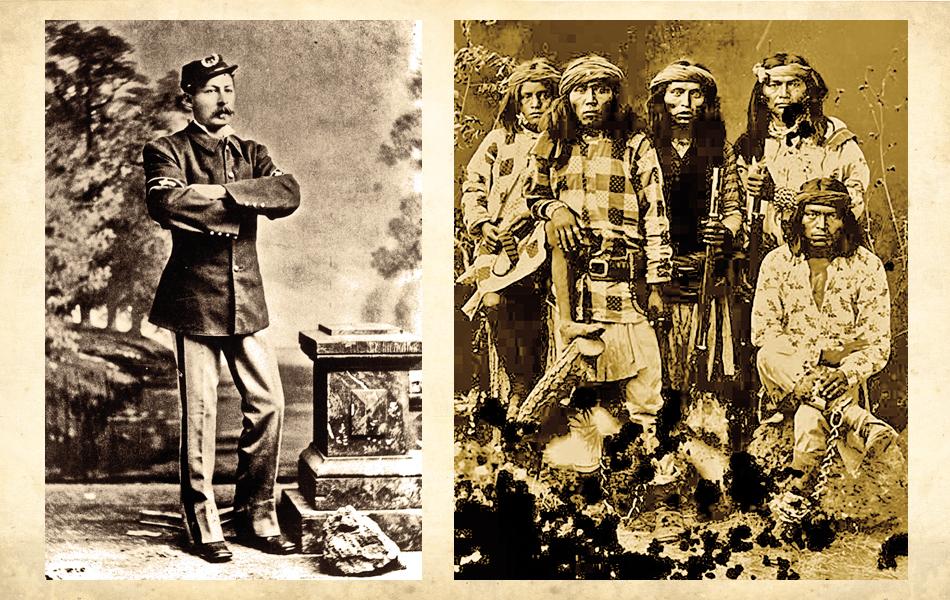

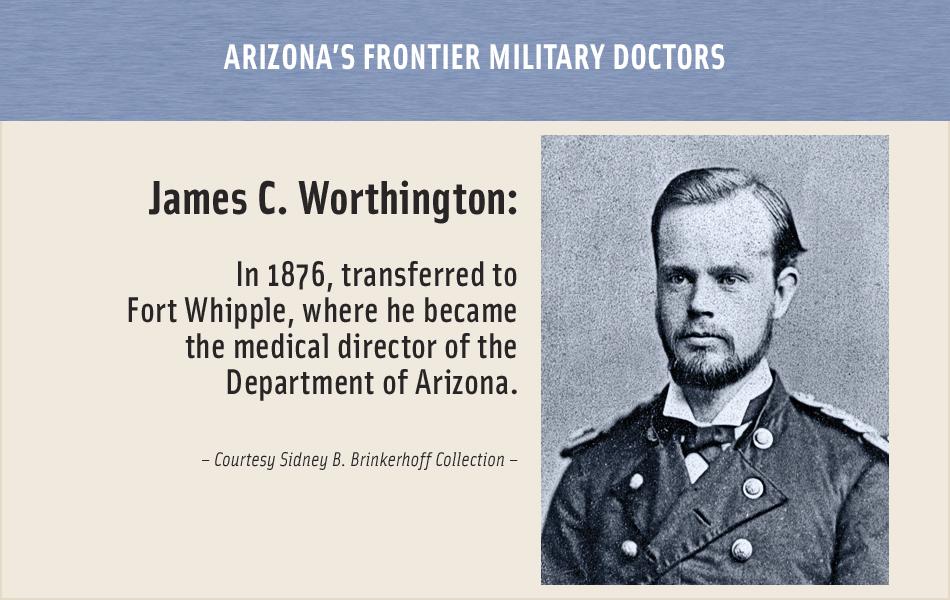

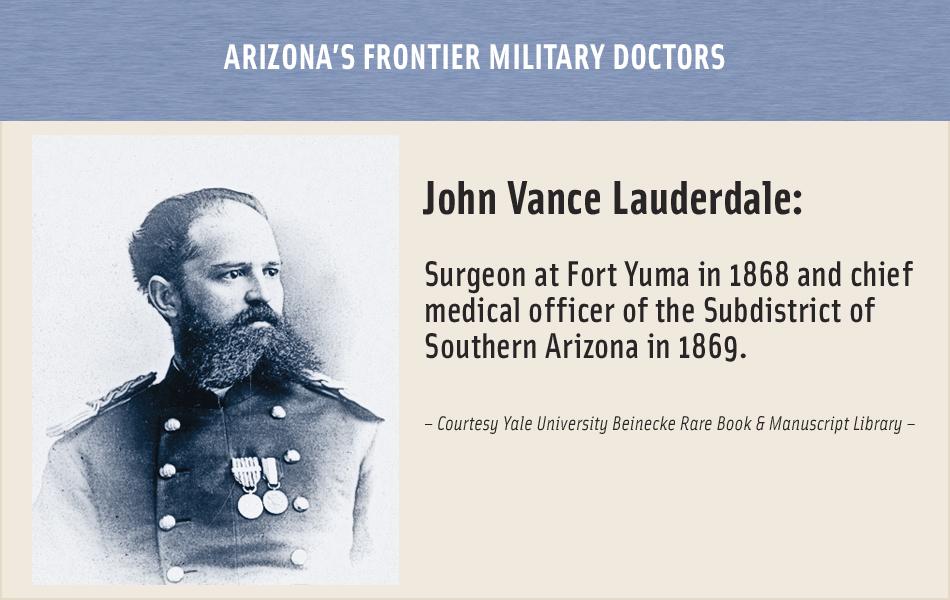

Whether on contract or as members of the regular Army, the scores of military doctors assigned to Arizona Territory, from the 1860s through statehood in 1912, ran the gamut. These men ranged from Civil War veterans, who came West in hopes of striking it rich, to young medical school graduates, who saw the Army as a means to further their budding careers.

Medical care stretched beyond a doctor’s garrison. As Fort Bowie’s post surgeon Charles Smart noted in his 1870 report, emigrants from Texas to California frequently called “upon the post medical officer for assistance and supplies for their sick and wounded.”

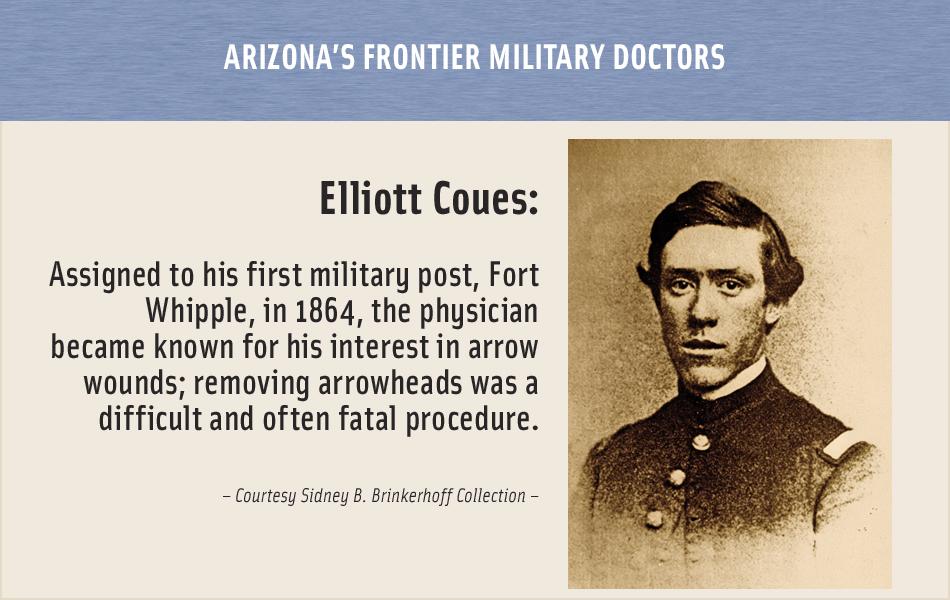

Some performed admirably outside their roles as healers. For instance, doctors recorded the weather until the Signal Corps assumed the mission after the Civil War concluded. A number of doctors turned their inquisitive scientific minds toward studying geology, flora, fauna, customs of the local peoples or antiquities discovered in their new surroundings.

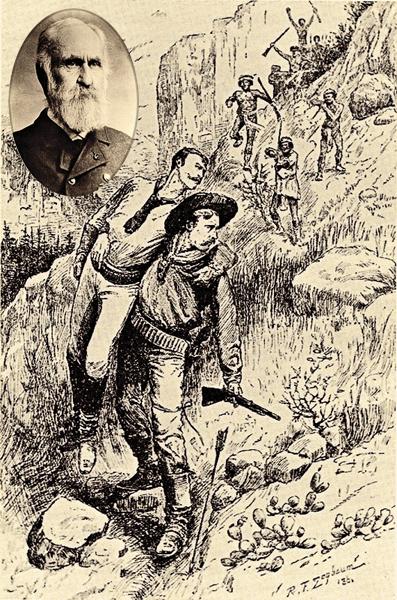

Several doctors received the Medal of Honor for valor under fire or for putting aside their duties as a doctor to serve in combat. These men faced the privations of campaigning during violent conflicts against Apaches and others that raged for decades. At least one doctor was a combat casualty himself; in 1871, Apaches wounded Dr. A.F. Steyer, resulting in the amputation of his arm.

Other doctors were not so valiant in their medical duties and were relieved for incompetence. One even went to prison for bigamy.

Regardless of the dangers of field service or the monotony of mundane medical responsibilities at one of Arizona’s scattered camps and forts, these surgeons in blue left behind a rich legacy, along with a healing tradition for those who followed in their footsteps.

John Langellier received his PhD in military history from Kansas State University. After a 45-year career in public history, he retired in Tucson, Arizona, in 2015. He is the author of dozens of books and continues to be a consultant to museums, film and television.

{

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Union Pacific Museum –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

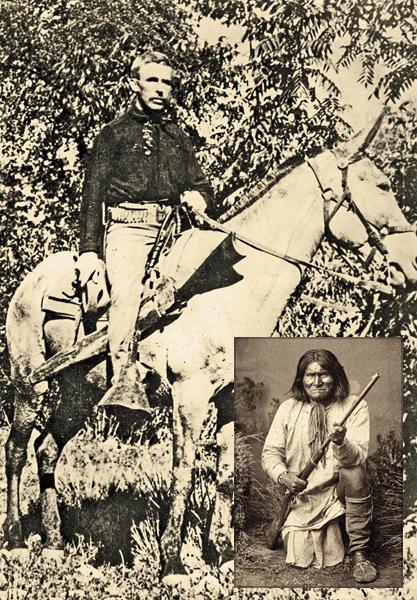

– Staubly photo Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration; Skippy photo True West archives –

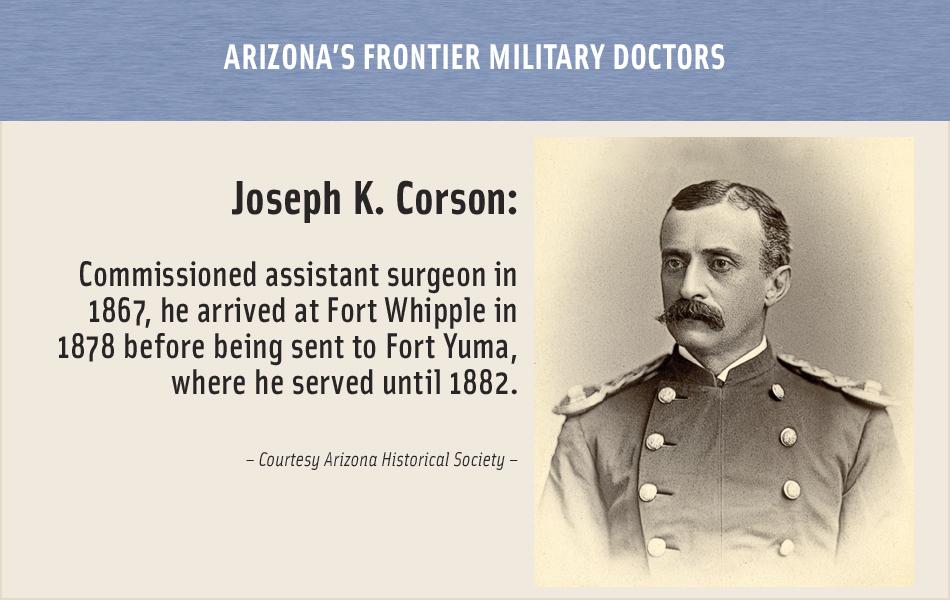

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

– All images courtesy Sidney B. Brinkerhoff Collection unless otherwise noted –

– Wood photo Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration;

– Courtesy Library of Congress –