The iconic pictures of the Mexican soldier and his soldadera wearing bandoliers embody the Mexican Revolution that began in 1910 south of our border. It ended ten years later, on November 30, 1920, after many military victories and political maneuvers, with the investiture of President Álvaro Obregón. But in September 1926, the New York Times reported that the Yaqui Indians initiated one of its last volleys, “kidnapping” Obregón on a train trip to Sonora. They had supported his revolutionary battles, but they now insisted he keep his promises to protect their land. Promises were made, but again Obregón fell short. Now, back to the revolution, what followed the initial proclamation were twists and turns that eventually pitted revolutionary against revolutionary: 10 long years with coups, civil wars, battles, assassinations and quite a few presidents.

CALL FOR REVOLT AGAINST DIAZ

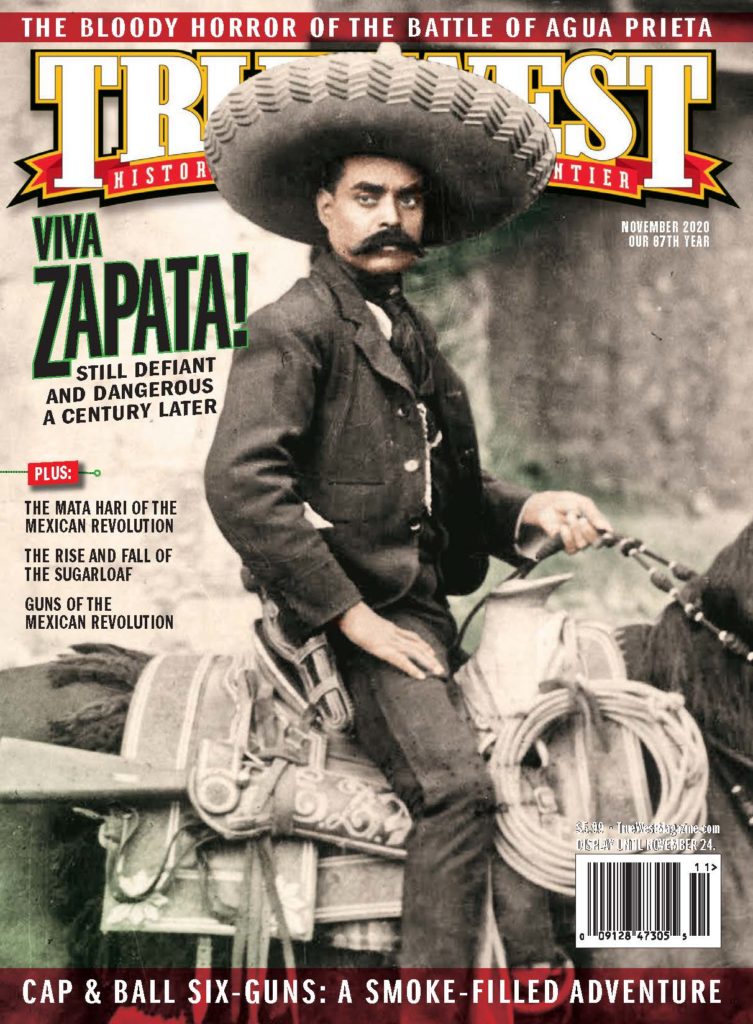

In 1910 Francisco Madero made the call to arms. His best-known followers and the heroes of the revolution are Francisco “Pancho” Villa, leader of the Northern Army, and Emiliano Zapata, general of the Southern Army. They rose to back Madero in his struggle against the dictator, Porfirio Diaz, a conservative who supported the landowning elite and foreigners to the detriment of the Mexican middle class and poor, especially the Indians and landless peasants. This struggle had been part of Zapata’s life a decade before the revolution drew him in. To Villa, it was new.

ZAPATA THE AGRARIAN HERO

In the southern state of Morelos, Zapata had years of experience fighting Diaz’s repressive actions. He had suffered at the hands of landowning hacendados, who wanted to control the land and water of the region (with Diaz’s help). He did not have to be told of the exploitation and suffering; he had felt it. With other peasant leaders, Zapata formed the Liberation Army of the South and marched to fight the federales, playing a major role in Diaz’s defeat. He participated in the pivotal southern Battle of Cuautla, which Diaz admits convinced him to renounce his presidency.

The Battle of Cuautla was especially difficult for Zapata, although his force outnumbered the federales ten to one. The elite federal force, of 300 to 400, was firmly ensconced in the town and at the highest points with machine guns—promising never to surrender. Zapata was used to guerrilla or fast attack tactics like his northern brother, Villa. Cuautla was a siege. Initially, several attacks were repulsed with a high casualty rate for Zapatistas. He lost more than 1,000 soldiers to machine guns and hand-to-hand fighting against Diaz’s elite. Eventually, Zapatistas used petroleum to burn out many of the federales. Due to that, and to running out of water and ammunition, the elite survivors fled on May 21, 1991.

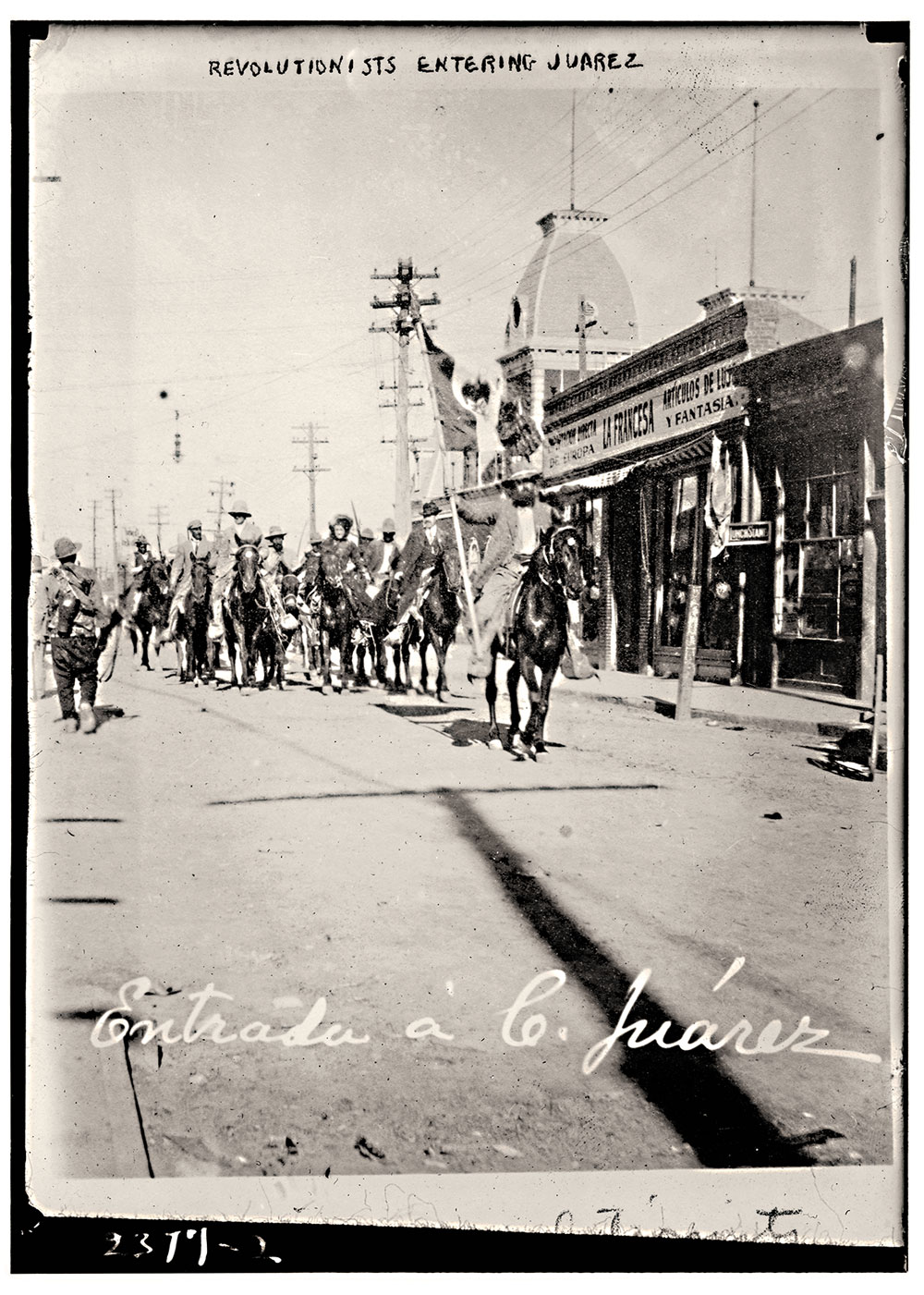

To the north, in the Battle of Ciudad Juarez in 1911, Villa, Madero and Pascual Orozco decided to lay siege to Ciudad Juarez. Madero, fearing U.S. intervention on its border, ordered a successful attack. Coupled with other defeats, a week later Diaz resigned and left for Europe.

Neither Villa nor Zapata had military training, so the victories were remarkable. Villa is often remembered because of his battles and “bandit-like” activities, mostly confined to Northern Mexico, including his incursion into the U.S. Villa is a controversial figure because of these activities. While publicly espousing the cause of the downtrodden peasants, many believe he joined the cause because he saw it as an opportunity to advance and was in it only for himself. None can deny, however, that he led the army to important victories that brought positive change. The fact that he robbed from the rich landowning hacendados, banks and train companies caught the attention of U.S. leaders, who called him a Robin Hood.

MADERO’S SHORT PRESIDENCY

It did not take long for Madero, as president, to renounce the Zapatistas as bandits and send federal troops under Victoriano Huerta to put down their “rebellion,” using a scorched earth policy. Losing trust in Madero, Zapata put out his Plan of Ayala in November 1911. Zapata denounced Madero and called for substantial land reforms, redistributing lands to the peasants. His slogan, “Land and Liberty,” was born. Zapata refused to disarm and fled to the mountains ahead of General Huerta’s attacks. Huerta destroyed villages, removed inhabitants and forcibly constricted the men to the army or labor camps. Zapata consolidated his troops and his role as defender of the peasants, eventually pushing Huerta out. Huerta returned to Mexico City and lead a coup against Madero, who was ultimately assassinated in 1914.

HUERTA’S BETRAYAL

Zapata left his southern stronghold and journeyed to the outskirts of Mexico City joining forces with the Constitutionalist forces in northern Mexico led by Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón, to contain Huerta. They ousted Huerta in July 1914. Zapata’s presence prevented Huerta from sending his entire army against Villa and the others in the north, allowing them—especially Villa—victory.

VILLA AS ROBIN HOOD

While he had done well with his local lieutenants, Villa’s growing international fame attracted journalists and foreign mercenaries with experience to his side. John Reed, a leftist journalist, spent four months with him and wrote Insurgent Mexico, that cemented Villa’s reputation as a Robin Hood. Reed described the military leaders as “unpaid, ill-clad, undisciplined; their officers merely the bravest among them armed only with aged Springfields and a handful of cartridges apiece.” Such was his reputation and he was invited to Fort Bliss to meet Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing—who tried to track him down two years later.

He raised money attacking haciendas and trains and through donations, which he used to modernize the army he took south, defeating Huerta in various battles, especially the Battle of Zacatecas in 1914. Unfortunately, the battle delayed him, and Carranza entered Mexico City ahead of Villa. Conflict was brewing.

CARRANZA WANTS POWER

Months later, in October 1914, Carranza called for a meeting. Villa refused to go and it was moved. In the Convention of Aguascalientes, they tried to reach an agreement, to no avail. Carranza expected to be designated president, but another was chosen. Carranza left, setting up a government in Veracruz on December 6. Mexico descended into civil war. Zapata reiterated his adherence to the Plan de Ayala, again reinforced his support of the indigenous peoples of Mexico, trying to bring reforms and the protections they had fought for. This legacy cemented a long-lasting peasant following, which Villa never achieved.

MEETING OF ZAPATA AND VILLA

Zapata’s army had taken Mexico City, and, interestingly, the peasant soldiers did not pillage and rape as had other armies, rather they surprisingly asked residents for food and water. On December 7, 1914, Zapata met his counterpart, Villa. The two leaders. Zapata, tall and thin and dressed as a charro; Villa at 180 pounds with a more robust body, dressed in khakis and a pith helmet. Although allies, they did not truly trust each other. One observer described the meeting as a coy encounter “like two country sweethearts.” Villa accepted Zapata’s Plan de Ayala and promised to fight with Zapata until a civilian president could be seated.

The two had several things in common. First, their popular origins appealed to the populace—the peasants. Neither would sell them out. Villa was driven to banditry. With the death of his “hero,” Madero, he took to robbing the rich and helping the poor in a haphazard manner. Second, they had an immediate common target—Carranza, the current nominal leader who had forgotten the revolutionary principles.

Zapata kept to his southern region, venturing out only as needed. The son of a horse trainer, he rose to power as a peasant leader. At his apex, he preferred wearing the traditional charro attire, slim silver-buttoned pants with pastel scarves; breaking horses (his father’s profession); and drinking. Like Villa, he sought the company of many a young damsel. Zapata struggled to recover the lost lands of the peasants, whose fierce loyalty was as unwavering as his dedication to the cause. Zapata used this time well and got down to enacting some agrarian reforms, trying to establish a Rural Loan bank and reorganize the sugar industry. He asked President Wilson’s envoy to meet with him, but Wilson had already recognized Carranza

The two leaders used their uncanny military skills with mobile forces and guerilla forces. To succeed they used the support of the lieutenants, who flocked around them from the countryside and the common people who followed them. Villa eventually had some foreign help, but the local leaders had little military experience.

CARRANZA AS PRESIDENT

Carranza called a constitutional convention and was elected president. From Veracruz, Carranza and Obregon, a superior tactician, waged a publicity campaign against Villa, portraying him as a sociopathic bandit. Villa was eventually forced out of Mexico City. With Carranza as his adversary, Villa roamed the north. Soon thereafter, Obregon defeated Villa in the Battle of Celaya and other northern battles, thus consolidating his power. The Division of the North was left in tatters. Villa was on the run. Desperate and disappointed with the U.S., he began to plan an incursion into the U.S. for more arms. In March of 1916, Villa committed his most audacious attack against the U.S., an incursion into Columbus, New Mexico, causing the death of dozens of Americans. President Wilson sent an expeditionary/punitive force under Pershing to capture Villa, but he eluded it for close to one year.

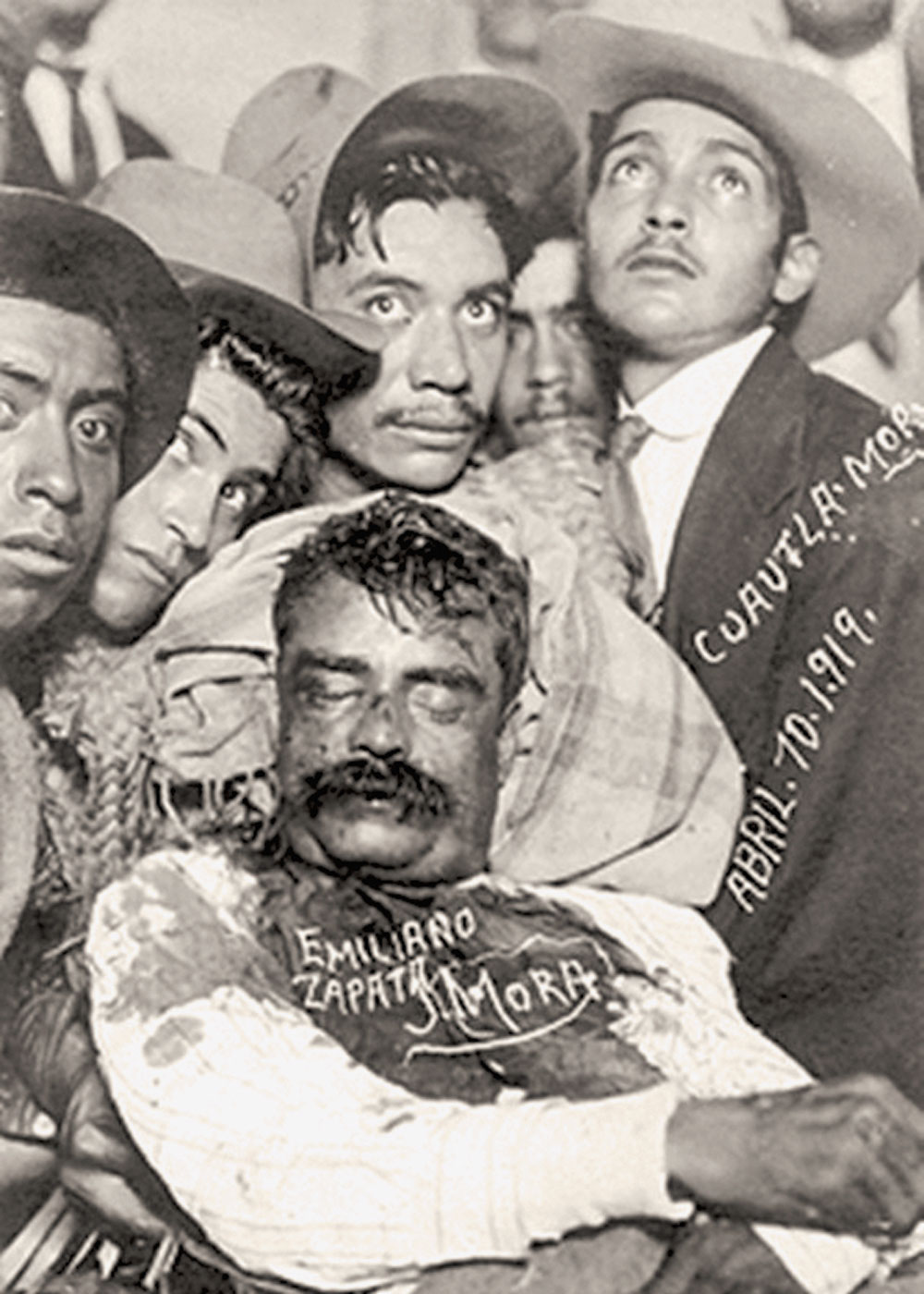

Meanwhile, Zapata occupied Puebla in 1917 but had to return to the south. William Gates, the new U.S. envoy, met Zapata. Gates wrote about him in a series of articles in which he contrasted Zapata’s orderly “constitutional zone” with the chaos of the rest of Mexico. Carranza attacked and Zapata had no choice but to fight against another scorched-earth offensive. After many battles and much suffering, Zapata took back Morelos in 1917. He was able to influence the writing of the Mexican Constitution, which would include Article 27 as a response to his agrarian demands. He continued the struggle until 1919, when Col. Jesus Guajardo lured him to a hacienda, where, coincidently, Zapata was ambushed and killed by Carrancista soldiers.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

OBREGÓN THE NON-REVOLUTIONARY

Zapata’s generals aligned with Obregón against Carranza, who was killed as he fled Mexico City with the treasury and documents. Obregon became president. The end was near. After ten years of war, war-weary peones returned to their haciendas and villages. Many southern and northern leaders, including Villa, reached deals with the government. He was pardoned and retired to his ranch. Later, as many feared Villa would rise again, he too was assassinated on the streets of Parral on June 20, 1923.

Capitalizing on their role in the Obregón victory, some of the Zapatista leaders were given political positions and ensured some gains for the peasants. Full protection was never achieved.

– Courtesy Libray of Congress –

LAST MAN STANDING

None of the original rebels achieved ultimate success. Interestingly, neither Zapata nor Villa sought national power. Zapata specifically fixed his goal as agrarian reform. Some argue that they were uneducated, provincial and tied to a vanishing rural way of life. The Constitutionalists—more often opportunists from the north, like their leader Alvaro Obregón—were more like entrepre-

neurs. Obregón used the Yaqui lands himself and doled out land to his cohorts. To keep the masses quiet, there was some token distribution to the peasants, but not as Zapata had envisioned. Radical ideas like agrarian reform circulated, were implemented in some places, and indeed, became part of the Constitution of 1917. Some argued that little changed, as much went back to the status quo during a political counter revolution.

But many things did change. The country was opened and ideas flourished. It was not until the administration of Lazaro Cardenas that some real political changes were made. Yet, 70 years later, the neo-Zapatistas found it again necessary to rise again—proof that Zapata’s agrarian dream had not been realized. Zapata’s dedication inspired the late 20th-century movement to fulfill the continued struggle of the peasants for justice.