The legacy of Gen. George Forsyth’s leadership in the famous battle remains controversial over 150 years later.

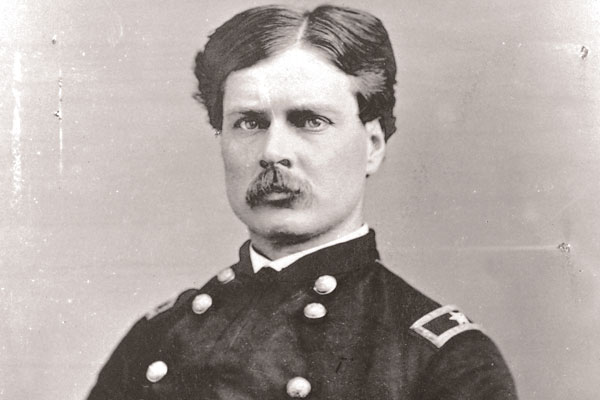

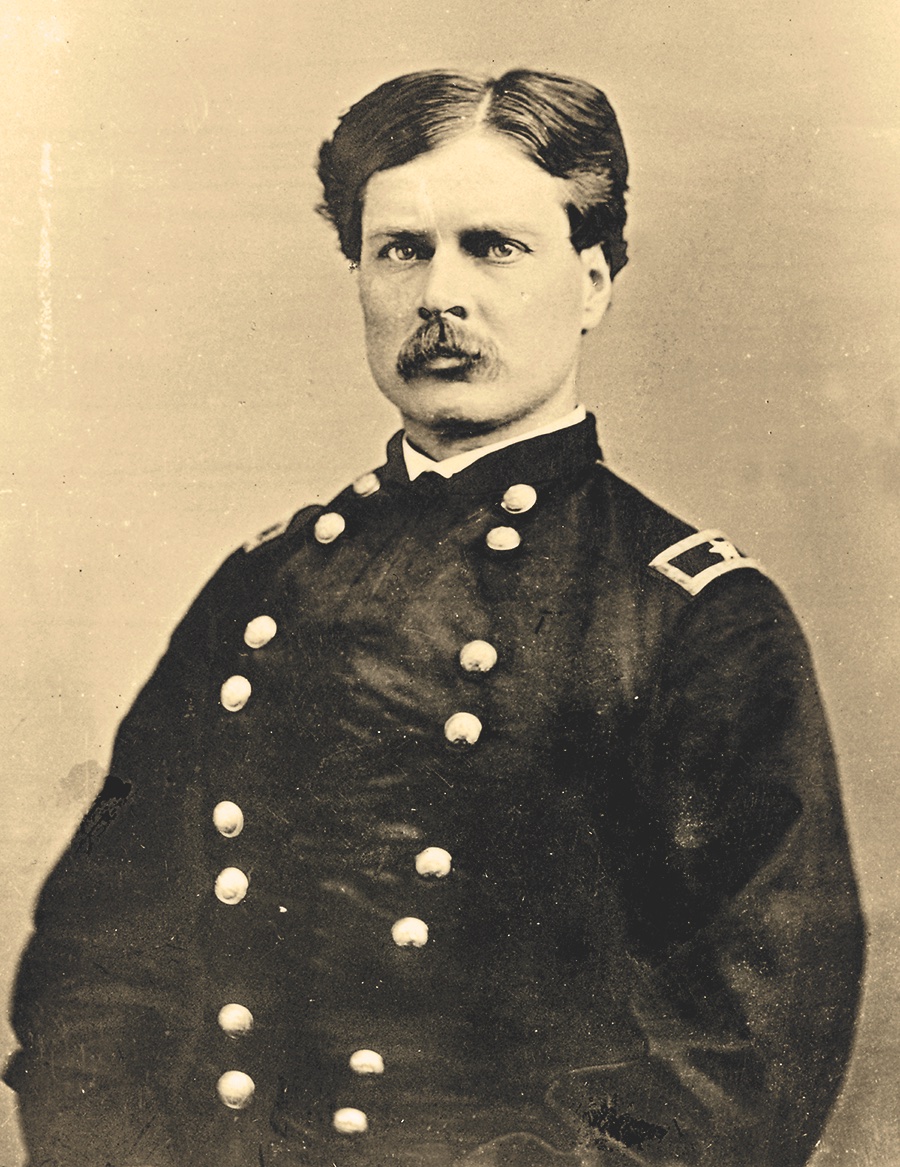

George “Sandy” Forsyth was a hard-charging cavalry officer—tough, brave and aggressive. He was also stubborn to a fault and willing to push his men to the limits of their endurance. Forsyth compiled an impressive combat record during the Civil War, but it was as an Indian fighter that he earned his fame and became known as the “Hero of Beecher Island.” In many ways, Forsyth was a hero, but some of his heroics occurred because of the bull-headed tactics that placed him and his men in desperate situations.

Rufus F Zogbaum, True West Archives

Born in Muncey, Pennsylvania, in 1837, Forsyth as a young man moved to Chicago, where he trained to be a lawyer. He volunteered to fight for the Union in 1861 and served with distinction throughout the Civil War, rising to the permanent rank of major and the brevet rank of brigadier general. Forsyth led cavalry troops in many hard-fought, bloody battles. During the course of the war, he contracted typhoid fever and was seriously wounded at the Battle of Brandy Station. He ended the war as a member of Gen. Phillip Sheridan’s staff. Forsyth’s association with Sheridan would propel the remainder of his military career.

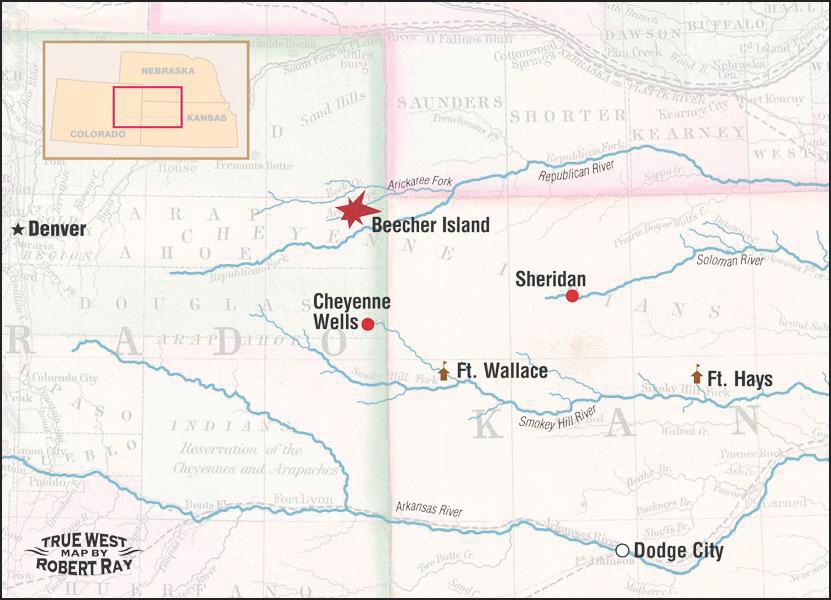

After the war, Forsyth was initially given a series of administrative and reconstruction duties, which did not appeal to his desire for action and adventure. Forsyth’s chance to return to combat duty came after Sheridan was appointed commander of the Department of the Missouri, a job that made the general responsible for keeping safety by pacifying the Indians in Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Missouri, Illinois and Indian Territory.

An 1868 series of Indian raids in western Kansas set in motion the events that would lead to Forsyth’s initiation as an Indian fighter. Sheridan ordered Forsyth to take command of a group of 50 volunteer scouts and to find and attack the Indian raiders.

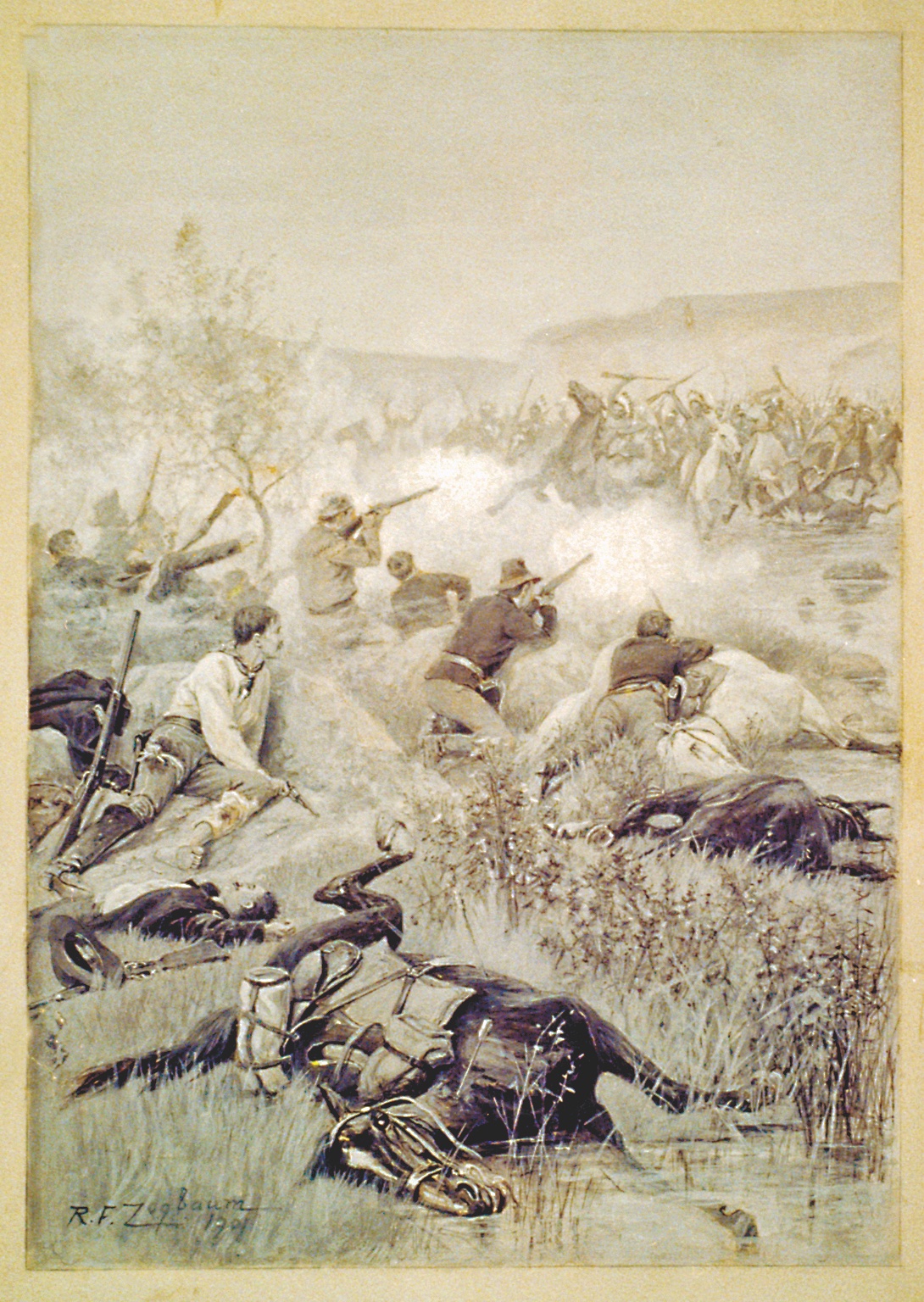

On September 17, 1868, Forsyth’s scouts held off a frontal attack by an estimated 900 Cheyenne, Sioux and Dog Soldiers. Forsyth’s men killed at least 32 Indians, including the famous Northern Cheyenne warrior Roman Nose, and wounded many more. The scouts also suffered severe casualties, with six killed and 18 wounded. Forsyth himself was shot in the right thigh, hit again by a bullet that broke his left leg and also shot in the head, suffering a skull fracture that knocked loose a small piece of his skull. In spite of his wounds, he continued to fight bravely and kept command of the scouts during the battle.

There was no question that Forsyth and his scouts fought courageously against desperate odds. The question is, should they have been trapped and attacked, in the first place?

The scouts first picked up the trail of the Indian forces near Sheridan, Kansas, where a raiding party had attacked a group of teamsters, killing two of the them and driving off much of the teamsters’ stock. The raiding party was estimated at around 25 warriors, and Forsyth led his men in pursuit of the marauders.

Over the next few days, the Indian raiders’ trail became hard to follow. The scouts continued to try to pick up the trail as Forsyth drove his men hard, covering 25 to 40 miles a day, sometimes without water. Eventually, the scouts picked up the trail again, which now began to widen, indicating a large band of Indians, far superior in number to the scouts. Some of the experienced scouts warned Forsyth that they were now facing a large force, but he insisted that the troops press on. He later said, “I had determined to find and attack the Indians, no matter what the odds might be.”

The scouts had another serious problem. They were running perilously low on supplies. They were only provisioned for a week, and they had been following the Indians for six days. At the beginning of their campaign they had been able to supplement their provisions by killing game, however the presence of the large band of Indians had driven the game out of the vicinity.

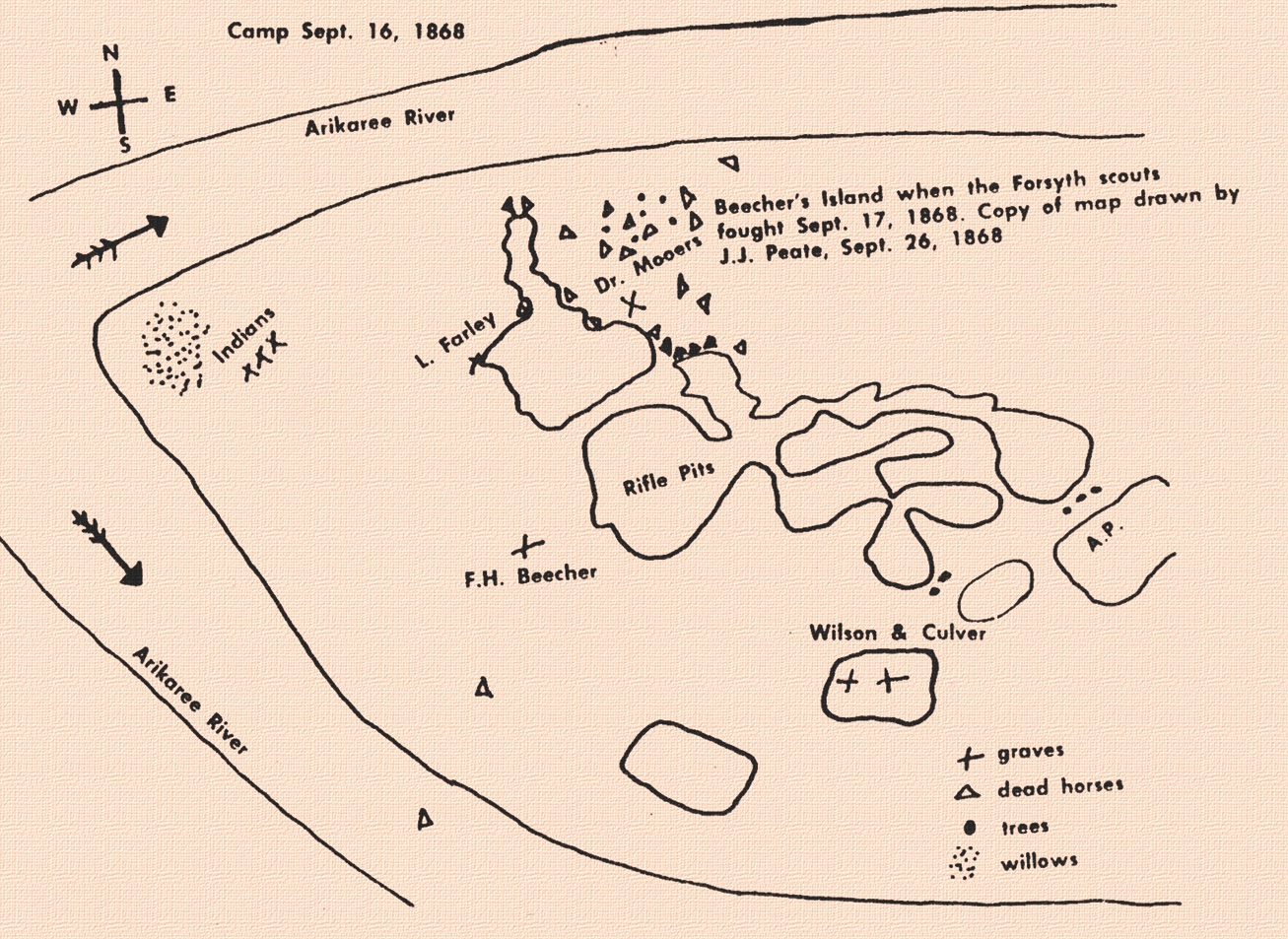

When the scouts were attacked on the sixth day, they were camped near a tributary of the Arikaree River in eastern Colorado. The scouts made their stand on an island in the river, which at that time of year was almost dry. The island became known as Beecher Island, named for Lt. Frederick Beecher, who was killed in the fight. The initial Indian attack drove off the scouts’ pack mules with the scouts’ meager remaining food supplies and all of their medical supplies.

After a fierce day of fighting and another few days of constant sniping, the scouts were stuck on the island with virtually no food and no medical supplies. At first they ate their horses, which had been killed by the Indians in the first hours of the fight. However, the horses’ bodies quickly began to spoil in the sun and became rancid and inedible. Without horses and with Indians still in the vicinity, the scouts could not travel far to look for food. The men began to starve, and many of the wounded men suffered infections, pain and complications from serious wounds. Finally, eight days after the battle, the scouts were rescued by a relief column.

The Battle of Beecher Island and its “hero” were lauded by Sheridan, who proclaimed a great victory. The press loved the story, and the battle was portrayed as a classic clash between fearless frontiersmen and a horde of wild savages. But should the scouts have been there at all? Forsyth had led his men into a trap, without proper food or medical supplies. He knew he was far outnumbered but recklessly pressed on in spite of being warned.

Part of Forsyth’s problem in leading his men into a trap was his disdain for the enemy. He had never faced Indians in battle and thought of them as an inferior, unsophisticated race. This attitude, coupled with Forsyth’s aggressive and stubborn personality, caused the battle to happen on the enemy’s terms, and only the courage and marksmanship of the scouts avoided disaster.

Later, in 1882, Forsyth’s attitude toward Indians had changed, but his impulsive aggression had not. Having largely recovered from his wounds and now a lieutenant colonel, Forsyth was placed in command of Fort Cummings in southwest New Mexico. Forsyth’s job was to protect the area from renegade Apaches who frequently crossed the border from Mexico or left the reservation and carried out raids on miners, ranchers and settlers. By now Forsyth had come to view Indians differently, describing the Apaches as “cruel, crafty, wary, quick to scent danger, equally active to discover a weak or exposed place within his reach, tireless when pursued, patient in defeat, and merciless in success, always seeking the maximum of gain at the minimum of risk.”

In April 1882, Forsyth learned that a band of Apaches had slipped across the border and persuaded or compelled some previously friendly Apaches near San Carlos Agency in Arizona to accompany them back to Mexico. As these Indians moved south toward the border, they raided and stole horses, sheep and mules.

Forsyth was determined to catch and attack the Apaches before they crossed into Mexico. Leading six troops of cavalry, he set out to hunt down the Indians. On the third day of the campaign, Forsyth had deployed seven Indian scouts under the command of Lt. D.N. McDonald to pick up the Apaches’ trail. The scouts were ambushed and trapped by the Apaches. Four scouts were killed, but McDonald was able to send one scout to notify Forsyth.

Upon learning of McDonald’s predicament, Forsyth galloped his entire command 16 miles across the desert to relieve him. An honorable act, but a killer for the horses and brutal for the men.

McDonald managed to escape the ambush and join Forsyth, who impetuously charged ahead into Horseshoe Canyon. In the canyon, the Apaches occupied the high ground. They were fortified by rocks and located hundreds of feet above the cavalrymen. Although Forsyth was in an untenable position, he pressed the fight, sending troopers climbing up the rocks, trying to flank the Apaches.

The Apaches rained down fire on the cavalry, as the Apaches slowly withdrew and escaped over the rim of the canyon, where they continued their dash for Mexico. After regrouping, Forsyth resumed his chase. The soldiers were lucky to only incur three killed and about eight wounded. The Apaches suffered only light casualties.

Once again, Forsyth had placed his command in a dangerous position and had driven his men to the limit. At the end of the chase and fight, Forsyth’s troopers and horses had traveled 78 miles, 16 at a gallop, in intensely hot weather, and had been 40 hours without water, except for about a pint at a small spring in Horseshoe Canyon.

Although Forsyth never caught up with the Apaches, he helped drive them into Mexico, where they were wiped out by the Mexican Army.

After attaining the rank of colonel, Forsyth was eventually forced out of the Army because of ruinous personal debts that interfered with his ability to serve effectively.

History mostly remembers Forsyth as the “Hero of Beecher Island.” He was certainly a brave soldier, but not necessarily a great leader.

Kent F. Frates is an Oklahoma City attorney and author. A previous contributor to True West, he has written four nonfiction books, including the award-winning Oklahoma’s Most Notorious Cases.

J.J. Peate Map Courtesy Roy B. Young Collection

Lonely are the Brave

Courageous Scouts and Buffalo Soldiers to the Rescue

At the end of the first day of the Beecher Island battle, the scouts had successfully fought off the attacking Indians, however Forsyth realized that his command was in perilous circumstances. They were completely surrounded by Indians, all of the scouts’ horses had been killed, and they were without food and medical supplies.

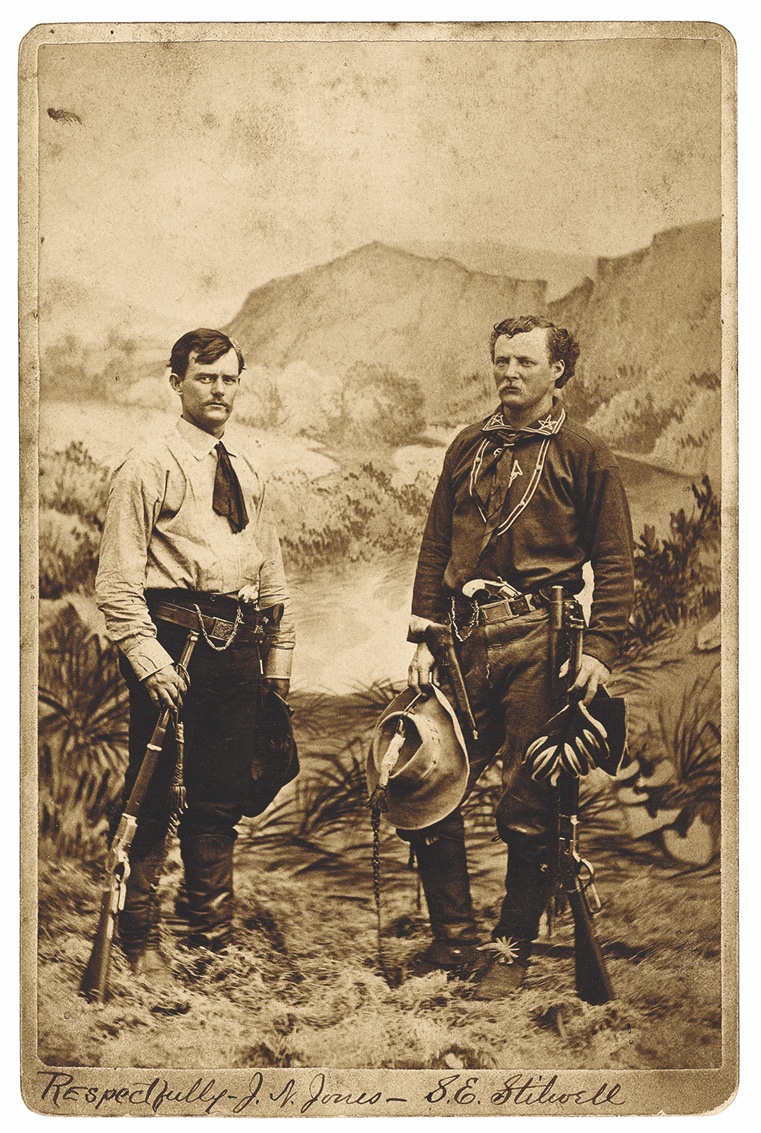

Forsyth determined to send messengers to Fort Wallace, approximately 85 miles away. S.E. “Jack” Stilwell and Pierre Trudeau were chosen from the scouts who volunteered. Stilwell was only 19 years old, but he could read a map, and Trudeau was an experienced frontiersman. Stilwell, who later was known as “Comanche Jack,” would become an Army scout, policeman, deputy U.S. Marshal, U.S. Commissioner, lawyer and judge. Around midnight Stilwell and Trudeau crept out of camp. They had cut off the tops of their boots and shaped them into makeshift moccasins and, at first, walked backwards so as to not leave tracks that might later alert the Indians. Their only food was a hunk of raw horsemeat and, they wrapped themselves in horse blankets in hopes of looking like Indians if detected in the dark.

Stilwell and Trudeau were only able to creep three miles the first night before sunrise. During the day, they hid in a ravine covered with tall grass. For three days they traveled at night and hid during the day, always with Indians close by. The third night they were near the Indians’ main camp and, with no other cover available, hid in the carcasses of dead buffalo.

Finally, after four days, the exhausted scouts, their feet pin-cushioned with cactus spines, reached a stage station west of Fort Wallace, probably at Cheyenne Wells. From there they got a ride into Fort Wallace on the stage from Denver, reaching the fort the next day.

Captain Henry C. Bankhead, the commander at Fort Wallace, immediately sent out couriers to find Company H of the 10th Cavalry, the famed Buffalo Soldiers, which, under the command of Capt. Louis H. Carpenter, were patrolling west of Fort Wallace. Carpenter immediately began a forced march toward Beecher Island. Bankhead and another relief column left Fort Wallace the next day guided by Stilwell.

After Stilwell and Trudeau had left the island, Forsyth worried that the two scouts might not make it, so he sent out two more pairs of scouts. The first two could not get through the Indians and turned back. Scouts Jack Donovan and Allison Pliley did make it to Fort Wallace after Bankhead had left. Donovan hurried west, located Carpenter’s troops and guided them to the island.

On September 25, eight days after the battle began, Company H arrived at Beecher Island. Bankhead’s command reached the island the next day with more food and medical supplies. Relief came just in time to treat the wounded and save the starving scouts.

When the relief column arrived, Forsyth, although shot to pieces, tried to show a lack of concern by sitting and reading a copy of Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist.