Courtesy John Wilder

“My parents loved Westerns. My mother’s family were pioneers; they were the first four wagons into Seattle, Washington. When I was five, in a little house on American Lake in Washington, we’d listen to the radio, to the Adventures of Red Ryder. Two years later I’m at the microphone doing the voice of the little Indian boy.”

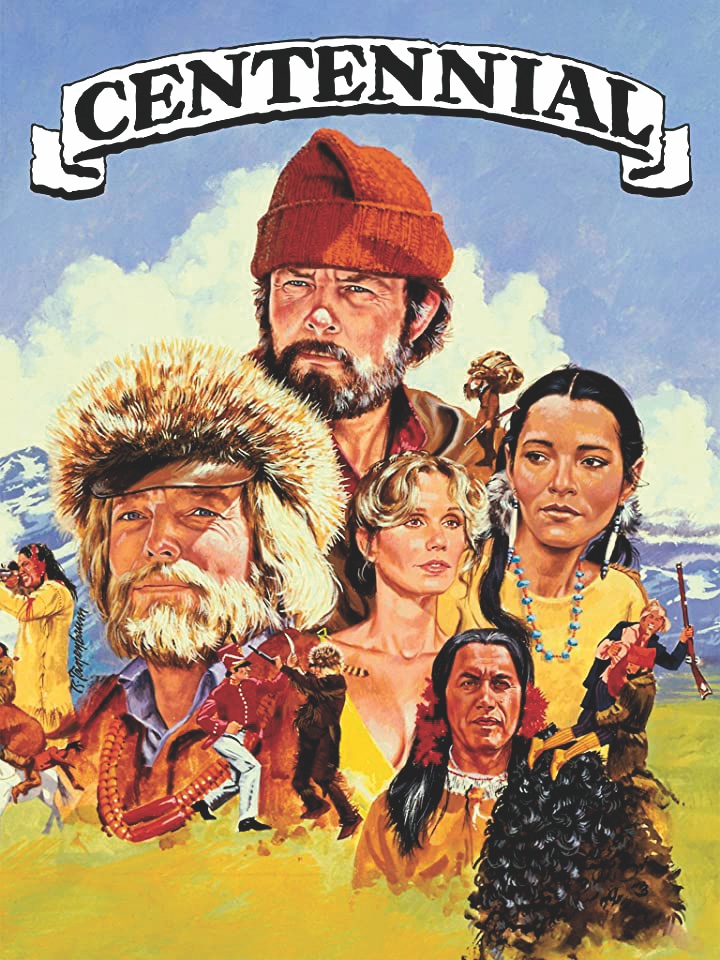

John Wilder’s journey from kid, to kid actor, to TV writer, to writer-producer seemed almost predestined to prepare him for the crowning achievement of his career: writing and producing the monumental 26-hour miniseries, James H. Michener’s Centennial. It also nearly did him in. “I had basically a nervous breakdown working on that,” he recalls. “My marriage blew up, my world fell apart because of the stress. I’ll never do anything as hard again; never anything I loved as much, because I loved the characters.”

Courtesy ABC Radio

“I had bad allergies as a little guy. The doctor told my parents to go east of the mountains, or south to, like, Pasadena.” Pasadena won. He was directed by Maria Riva, Marlene Dietrich’s daughter, in a production of Lillian Hellman’s Watch on the Rhine. “She took my mom aside and said, ‘Johnny can read way above his years, and in radio they look for children that can read.’ So [Mom] took me over to CBS for a general audition, and the next day [we] started getting calls. Within a month, I was doing Lux Radio Theater. In the five years I worked radio a lot, I had 13 running roles on different series.”

Among Wilder’s other radio appearances, starting in the late 1940s, were The Jack Benny Show, The Roy Rogers Show, The Gene Autry Show and he starred in the radio version of The Adventures of Champion.

Maynard and Shirley Patterson.

Courtesy Producers Releasing Corporation

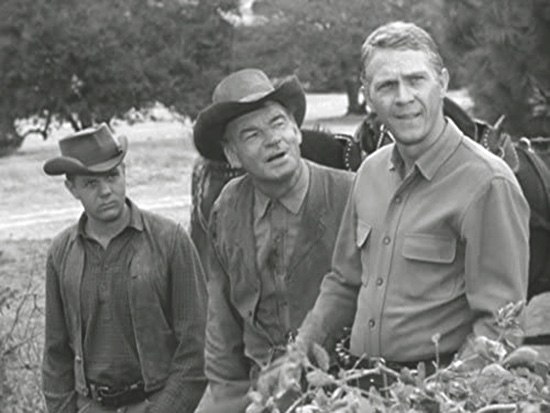

The world of early television opened up opportunities for adventure, not all of them pleasant. “People think it’s all make-believe. But I almost rolled a stagecoach [on Rin Tin Tin], almost got mauled by a lion [on Circus Boy], and on Broken Arrow, the wad from a blank set my face on fire.” But there were many more positive experiences: working with Lloyd Bridges on Zane Grey Theatre, and making friends with Steve McQueen on Wanted: Dead or Alive.

He graduated from Van Nuys High, and started at USC on a baseball scholarship. He had leading-man good looks, but, he says, “I wasn’t going to be a star. I really wasn’t a character actor. So, I thought I should direct. And I started writing.”

Courtesy CBS Television

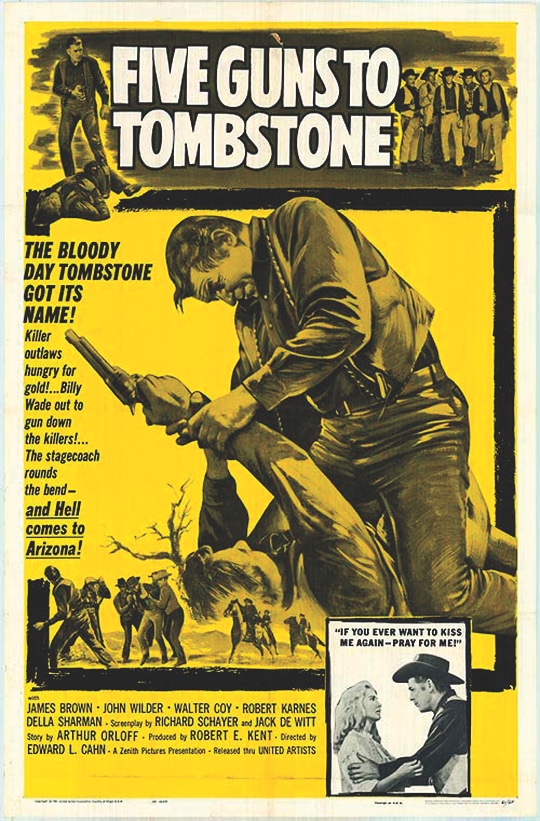

Film work both paid for, and interrupted, his education—The Benny Goodman Story, Summer Love, Five Guns to Tombstone. But his most important role was in the World War II movie Hold Back the Night. On location, he bonded with roommate Chuck Connors over baseball. “And that changed my life because Chuck knew I wanted to get behind the camera. He got cast as The Rifleman, called me and said, ‘You’re going to write an episode.’” Frustratingly, that sale didn’t lead to more work. “Friends who could’ve thrown me a bone, didn’t. I couldn’t get arrested.” Just as he was starting Loyola Law School, he “got a call from Chuck. ‘I just got a series, Branded. You’re going to write all my dialogue,’ what he called John Wayne dialogue: good and tight and lean. I went onto Branded as a story editor. It was terrific.”

From there Wilder moved to the hottest show on TV, Peyton Place, writing 119 episodes, then to Universal, then to Quinn Martin, writing and producing Streets of San Francisco. “I loved it,” but as he told Quinn when he left,” I really want to be doing what you’re doing.” Wilder was set to run drama development at a little Grant Tinker start-up called M.T.M. Until lunch with Universal President Frank Price changed everything. Price asked, “‘What can I do to get John Wilder to come back to Universal?’ I said, you have one property, Centennial. And he said, ‘That’s yours.’” This was the time of the grand miniseries. Roots, in 1977, was 10 hours long. “I’ve got a commitment for 13 hours,” Price told Wilder, “and an option for 13 more.’” Wilder bailed on M.T.M.

In his vast and wonderful novel, Centennial was the name Michener bestowed on a fictional town that was a microcosm of the history of Colorado, as well as a cautionary tale. “Michener’s ultimate message,” says Wilder, “[is] that we have an obligation to take care of the planet, and we’re not doing a very good job of it. It’s the ultimate ecological editorial, to see how the Indians lived with the land and thought only the rocks live forever. Who are the villains of Centennial? The real estate brokers.

Courtesy United Artists

“Centennial spoke to me because there are moments in [my] family history that were replicated in Jim’s book. Like the part that Dick Crenna played. We called him Skimmerhorn, but it was really Chivington, and it was the Sand Creek Massacre.” Although he wasn’t contractually obligated, Wilder sent every script to Michener for his approval. Michener loved appearing in the opening. They were close friends for the rest of Michener’s life.

“My philosophy of producing television was, get the material as good as you can in the time you’re allotted, hire a director who’s a shooter, and hire bulletproof actors.” With 128 characters in a 900-page story that reaches from the 1740s to 1974, casting was an immense job.

For the first important character, Lame Beaver, he wanted Michael Ansara, who’d played Cochise with him on the Broken Arrow series. “Michael, please tell me you have native American heritage. And he said, ‘No, but I’m blood brothers through the ceremony with five nations.’ I said, that’ll do.” For his daughter, Clay Basket, he wanted Barbara Carrera. “Any Native American heritage? ‘Well, I’m Nicaraguan. And that’s Indian.’ That’ll do.”

Courtesy NBC Television

The core character for the first several episodes was a feisty, heroic French-Canadian trapper named Pasquinel, the first white man in the region. Richard Chamberlin would be McKeag, his Scottish partner. Carrera would be his wife, and Sally Kellerman would be Lise Bockweiss, his other, German, wife, “and she learned German, as did [her father] Raymond Burr.” But who could play Pasquinel? Robert Conrad had been vigorously campaigning for the role, but was he a strong enough actor? A moving episode of Baa Baa Blacksheep suggested he was. They met. Wilder had three provisos he insisted upon, that Conrad wouldn’t like. This was no Maurice Chevalier role: he’d have to learn an authentic French-Canadian accent. Pasquinel’s wife is described as larger than her husband, and Kellerman was four to six inches taller than Conrad. And he’d have to say to her, “Maybe I’m a coward,” words that the genuinely tough actor would despise uttering. Finally, “Richard Chamberlain is playing McKeag. We both know that he’s gay. The line of dialogue I won’t let you change is, ‘Maybe you’re a better man than I am.’ I’m trying to do an authentic movie. If you can’t do those things, it’s not going to work. And Bob said, ‘Hey man, I’m an actor,’ and we shook hands.”

Courtesy NBC Television

A few days into shooting, the tiny amount of footage coming in indicated that the wrong director had been chosen. Wilder remembered a director he’d used on Streets of San Francisco. “Virgil Vogel is an artist. He’s not the most articulate man, he doesn’t talk to actors at all, but boy, does he know where to put the camera. I sent him the script, he came into my office in the morning, and he cried. He said, ‘I’ve been shooting shit all my life. And you send me something this beautiful, and I don’t have time to prepare.’” Wilder offered to shut down the set to give Vogel three weeks to prepare, but Vogel flew up that night, “And, by God, he gave me more film that afternoon than the other director had given me with weeks to prepare.” Vogel, Conrad and many in the cast and crew considered Centennial the best work of their careers.

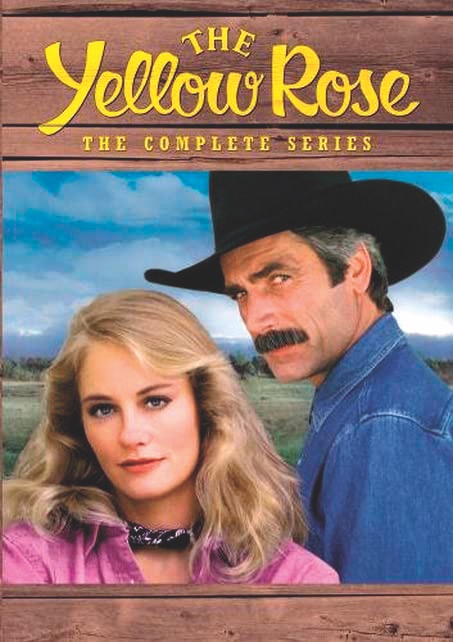

back into TV Western series when he

created The Yellow Rose, starring Sam Elliott and Cybil Shepherd, for NBC in 1983.

Courtesy NBC Television

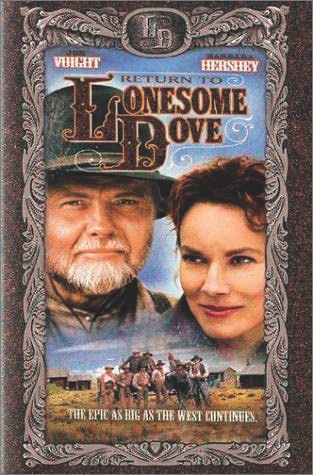

Since Centennial, Wilder has produced and written many shows, notably creating the contemporary Western series The Yellow Rose, and developing Spenser: For Hire. In 1993, Jeff Sagansky, who had been an executive’s assistant on Centennial, was now the president of CBS, and asked Wilder to write and produce a sequel to the miniseries Lonesome Dove. “It’s a great novel, a Pulitzer Prize winner. What could I do with that story? It ended. What’s left? And I thought, father and son. Newt is Call’s son, but Newt doesn’t know it, and Call won’t admit it. So I sat down and wrote the last scene of Return to Lonesome Dove, where they say goodbye, and Call, in effect, gives him his name without saying, you’re my son. And it made me cry at the typewriter. I thought, okay, that’s powerful. I called Jeff and said, I’m in. My agent said, ‘Don’t; sequels are never any good.’ And I said, ‘Nobody’s making Westerns. I love Westerns. And I think I can do a good job, and that’s good enough for me.’

“Why do we keep coming back to Western stories? The best of them are about right and wrong, meeting challenges, of maintaining integrity and honor, at least the Westerns that you and I love.”

Courtesy CBS Television

BLU-RAY REVIEW

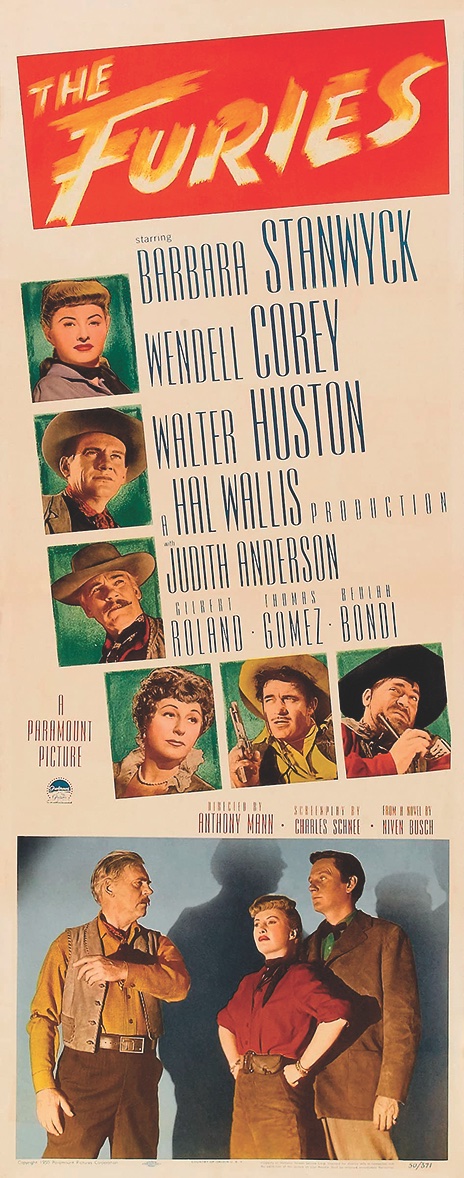

The Furies

(Criterion Collection; $39.95) Often overshadowed by his brilliant Western collaborations with James Stewart, Anthony Mann’s The Furies is a noir masterpiece. Walter Huston, in his final, exuberant performance, is T.C. Jeffords, a New Mexico rancher so arrogant that he prints his own money. Western goddess Barbara Stanwyck is his daughter in this Freudian nightmare, trying to save the ranch from her profligate dad, while drawn romantically between two men he’s wronged: patrón-turned-squatter Gilbert Roland, and Wendell Corey, who tells her, “You’ve found a new love in your life. You’re in love with hate.” Sparks fly—as do scissors! Victor Milner’s Oscar-nominated black-and-white photography accentuates the stark Arizona locations and massive sets. The Criterion Collection set includes shorts, interviews with Mann and the novel by Niven Busch.

Henry C. Parke, Western Films Editor for True West, is a screenwriter, and blogs at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com. His book of interviews, Indians and Cowboys, will be published later this year.

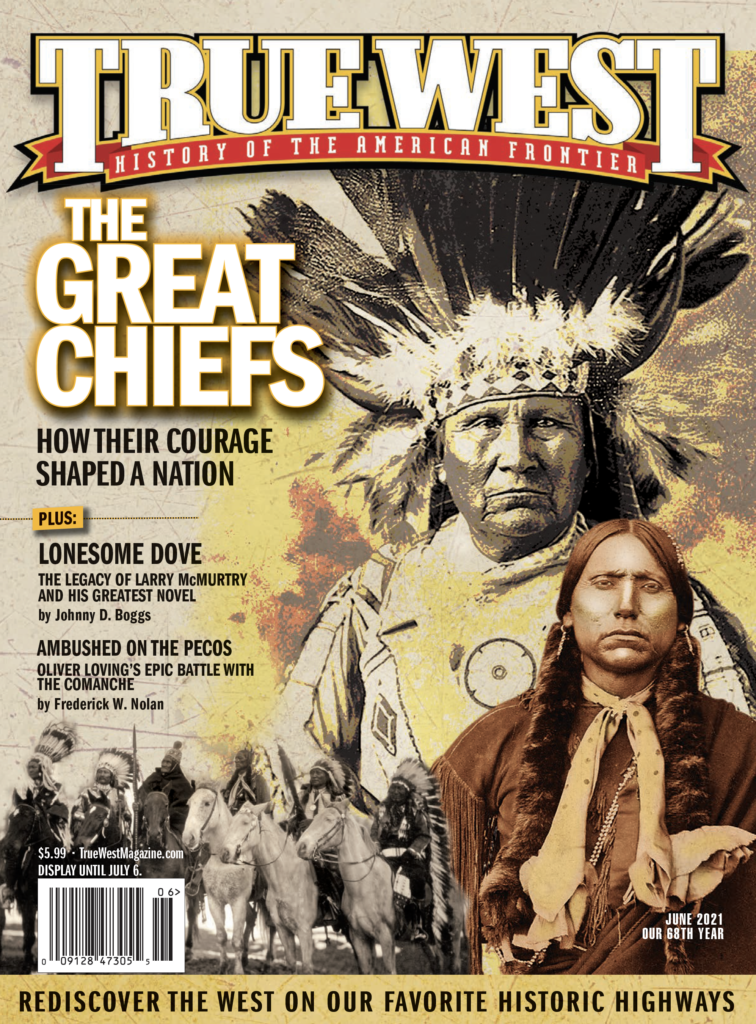

A Flock of Lonesome Doves

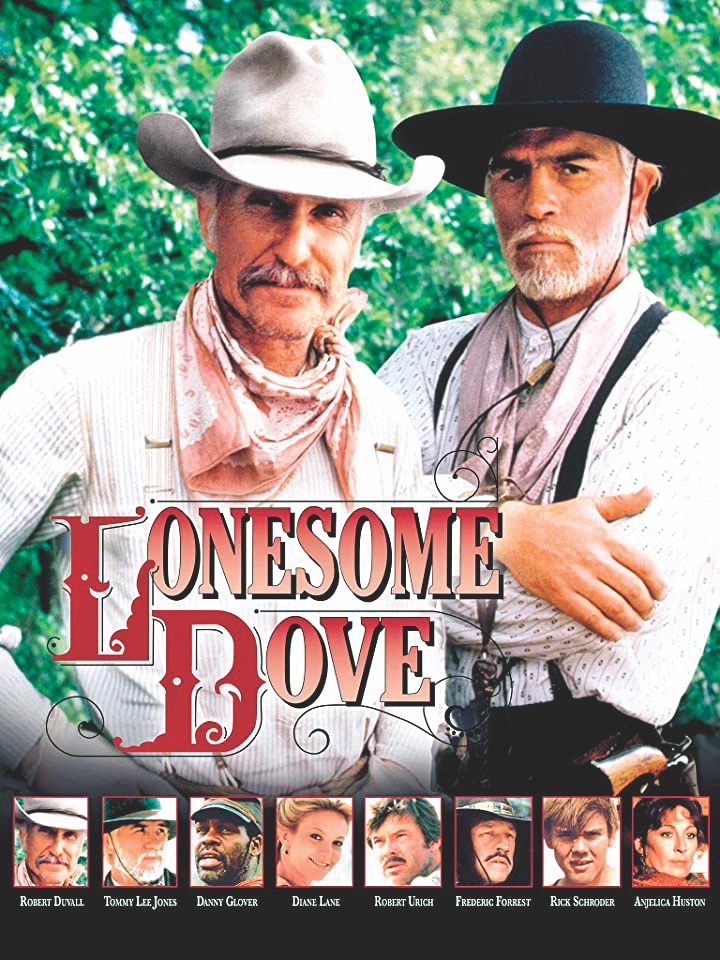

How could it fail? Novelist Larry McMurtry’s Horseman, Pass By had become Hud, and won three Oscars. The Last Picture Show won two, and its director, Peter Bogdanovich, loved Westerns as much as McMurtry, and was friends with every important Western director and actor alive. They collaborated on a screenplay, Streets of Laredo, signing John Wayne as Woodrow, James Stewart as Gus, and Henry Fonda as Jake Spoon! Only then, Wayne backed out. And the script went on the shelf.

McMurtry kept writing novels and scripts. Some movies were hits, like Terms of Endearment; some vaporized, like Lovin’ Molly (adapted from his novel Leaving Cheyenne). And one day, McMurtry spotted a bus with LONESOME DOVE CHURCH painted on its side, put that name on the script on the shelf, and wrote it into a novel that would win him the Pulitzer Prize.

The 1989 miniseries was so beloved, the characters so endearing that, despite killing off the favorite, Gus, a sequel was inevitable. In 1993, John Wilder, who’d scripted and produced Centennial, wrote it, with McMurtry okaying the script. Rick Schroder returned as Newt, and when Tommy Lee Jones didn’t want to do a sequel, Jon Voight played Woodrow. Voight had been first choice to play Woodrow in the original, but didn’t like the treatment of Indians in the novel or script, and passed. He liked this script a lot, and when producers tried to make changes, he redistributed the original blue-paged draft—which he called “the blue bible” —to cast and crew, and insisted they stick to it. That same year, McMurtry, recovering from heart surgery, wrote an excellent sequel novel, using the original title, Streets of Laredo. Lonesome Dove had become a franchise.

In September of 1994, Lonesome Dove—The Series appeared. When Rick Schroder passed on playing Newt again, they cast Scott Bairstow, a competent actor who, 10 feet away, couldn’t be distinguished from Schroder.

In September of 1995, McMurtry published the next fine Lonesome Dove novel. Dead Man’s Walk was not a sequel but a prequel, making it possible to bring Gus McRae back. On the downside, knowing what will happen, and learning how the characters got there, is rarely as compelling as a forward-told story. That same month, the series, now rechristened Lonesome Dove—The Outlaw Years, returned.

In November, the Streets of Laredo miniseries premiered, with James Garner as Woodrow, and Sissy Spacek as Lorena, Diane Lane’s iconic role from the original, and a wonderful supporting cast. McMurtry scripted with Diana Ossana, who was his nearly constant collaborator for the last 28 years of his life. Later, they would share an Oscar for scripting Brokeback Mountain, a story of shepherds who realize they are gay.

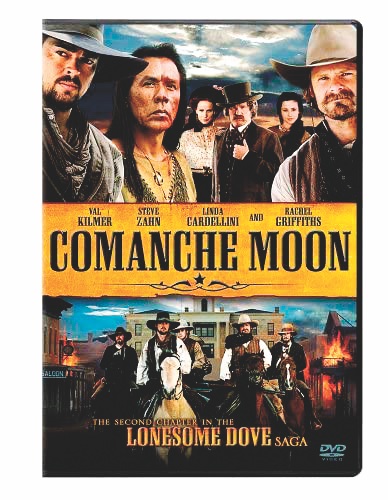

Six months after Streets, Dead Man’s Walk premiered, with David Arquette as a stripling Gus, and Jonny Lee Miller as an already conflicted Woodrow; characters who hold little promise in their youth and are overshadowed by other familiar actors. A year and a half later, McMurtry published the final Lonesome Dove novel, Comanche Moon. In 2008, more than a decade later, the miniseries appeared, with Steve Zahn as Gus and Karl Urban as Woodrow. Its smaller budget is evident, and again, the supporting players more compelling than the leads, but original Lonesome Dove director Simon Wincer helped make it worth watching, which they all are.

—Henry C. Parke