The life and times of the legendary Western writer and the legacy of Lonesome Dove.

“Sometimes Sonny felt like he was the only human creature in town.”

Those were the first words I ever read written by Larry McMurtry, who died March 25 at age 84. They certainly weren’t the last.

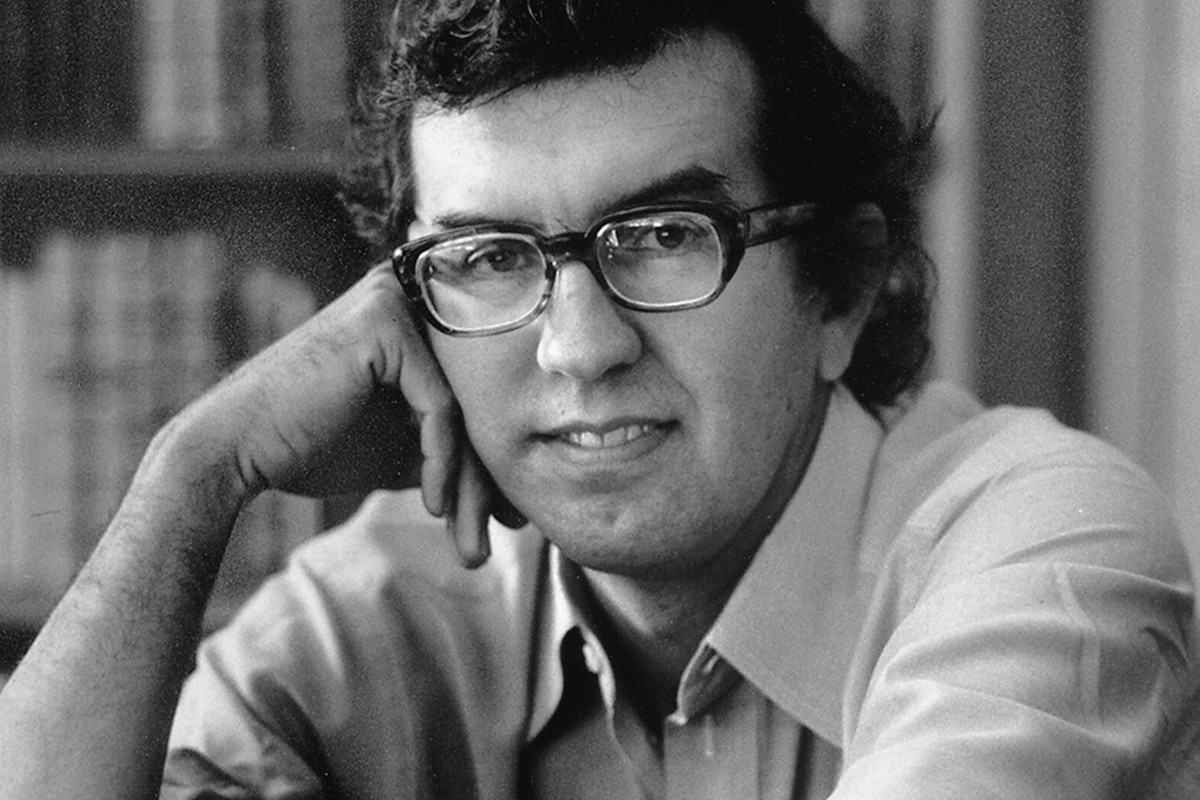

Photo by Diana Walker, 1978, True West Archives

In 1984, as a young reporter at the Dallas Times Herald (and a Texas transplant from South Carolina), McMurtry was required reading, so I devoured The Last Picture Show, Leaving Cheyenne and Horseman, Pass By—his first three novels—in my apartment. Back then, McMurtry was known for wearing a sweatshirt that identified him as a “Minor Regional Novelist.”

Regional? Yes. Minor? Debatable. Not many minor writers see their first three novels turned into motion pictures. But McMurtry was what Pat Conroy was to South Carolina, and what Max Evans and Tony Hillerman were to New Mexico. A regional writer who attracted readers outside his region. McMurtry wrote about the 20th-century West—sometimes putting contemporary cowboys in urban settings, as in Cadillac Jack (1982), about a bull-dogger turned antique scout in Washington, D.C. And often skipping cowboys altogether; Somebody’s Darling (1978) chronicled a woman director in Hollywood. In one interview, McMurtry said Western writers should give up the mythical frontier and focus on the modern West.

Ironically, when I read that quote, McMurtry had to have been writing what would become his masterpiece.

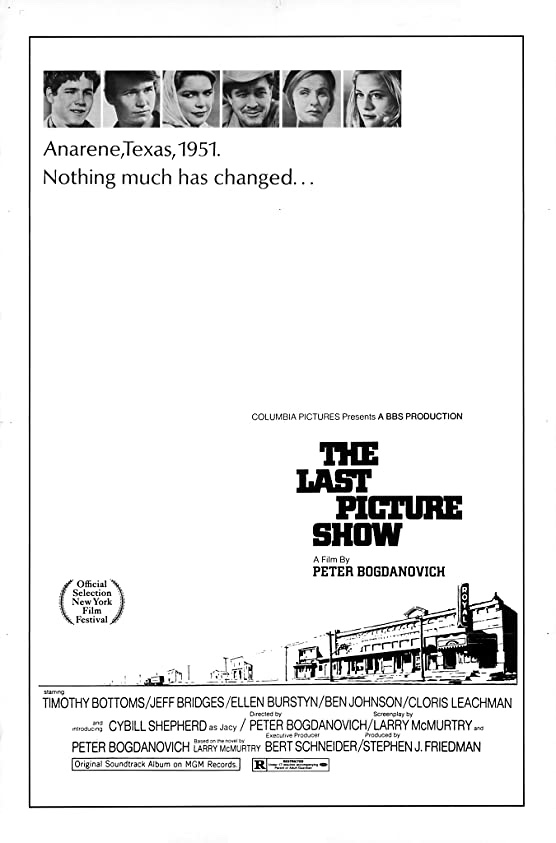

In 1985, Simon & Schuster published Lonesome Dove, an 843-page novel about an 1870s cattle drive from Texas to Montana, but McMurtry’s story began much earlier. Peter Bogdanovich, who had directed The Last Picture Show (1971), and McMurtry planned a period Western movie, Streets of Laredo, that would star John Wayne, James Stewart and Henry Fonda. “They were to be old cowboys that had tumbled into their last adventure,” McMurtry told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 1987. “When their adventure was over, the West was over.”

On his way to a steakhouse, McMurtry passed a school bus on the side of the road. Painted on the bus’s side was: Lonesome Dove Baptist Church. “I knew Lonesome Dove would make a great title,” McMurtry said in that 1987 Star-Telegram profile. “Five years passed before I put the name on the bus with the story in the screenplay and wrote Lonesome Dove.”

When Streets of Laredo never got out of development, McMurtry bought back the rights and started writing the novel, pecking away at it when he found time while focusing on Cadillac Jack and The Desert Rose (1983). He set out to trash the myth of the cowboy. Readers took his tale entirely differently.

Courtesy CBS Television

Lonesome Dove’s sales skyrocketed. It won the Spur Award from Western Writers of America and the Pulitzer Prize and was adapted into an equally successful CBS miniseries in 1989.

It wasn’t that publishers had shunned literary fiction set on the American frontier before Lonesome Dove. Douglas C. Jones’s The Court-Martial of George Armstrong Custer (1976), Brian Garfield’s Wild Times (1978), Lucia St. Clair Robson’s Ride the Wind (1982), Ron Hansen’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (1983) and Ivan Doig’s English Creek (1984) were success stories, but Lonesome Dove took success to an entirely new level for Western fiction.

Other well-received novels—Gary Matthews’ Heart of the Country (1986), Pete Dexter’s Deadwood (1986), Elmer Kelton’s The Man Who Rode Midnight (1987), Glendon Swarthout’s The Homesman (1988), Jane Candia Coleman’s Doc Holliday’s Woman (1995)—followed. McMurtry also opened the doors for many new, young writers of the American West.

None came close to matching Lonesome Dove’s landmarks.

“Now it seems to be replacing Gone With the Wind as a national epic,” McMurtry told the Los Angeles Times in 1989.

The Texas ranch kid who had once said 20th-century writers should not write about the 19th century began producing more Westerns set in the 1800s, including Lonesome Dove sequels and prequels—Streets of Laredo (1993), Dead Man’s Walk (1995), Comanche Moon (1997).

Lonesome Dove also made McMurtry a “captive,” as he told The Arizona Republic in 1995. When The Late Child was published that year, McMurtry said: “I like it a lot, but I suspect it’s going to be treated like a little orphan book slipped in around the Lonesome Dove books.”

Courtesy Columbia Pictures

McMurtry’s other period novels hit the bookshelves: Anything for Billy (1988), Buffalo Girls (1990), Zeke and Ned (1997), Boone’s Lick (2000) and his Berrybender series about a troubled 1830s hunting expedition: Sin Killer (2002), The Wandering Hill (2003), By Sorrow’s River (2003), Folly and Glory (2004).

Not all captivated critics.

While most of us never read McMurtry expecting historical accuracy (just mesmerizing prose), McMurtry’s treatment of history and the Cherokees in Zeke and Ned enraged a number of high-profile and well-respected Western novelists, including Cherokee Robert J. Conley and best-selling Don Coldsmith, the latter saying that many Cherokees refused to speak McMurtry’s name after Zeke and Ned.

Courtesy Paramount Pictures

McMurtry’s fiction began getting mediocre reviews, and sometimes not even that. “If you’re looking for another Lonesome Dove,” the Des Moines Register said of By Sorrow’s River, “you’ll be disappointed.” “McMurtry has tipped away from realism and the concrete into the cartoonishly absurd,” the Austin American-Statesman said of Folly and Glory.

Perhaps McMurtry thought the same. “Eventually all novelists, if they persist too long, get worse,” McMurtry wrote in Books: A Memoir. “No reason to name names, since no one is spared.”

But McMurtry kept producing at a Louis L’Amour pace, not just fiction, but nonfiction. While Crazy Horse (1999) garnered good reviews, other titles were ripped. “You’d think that Lonesome Dove creator McMurtry would add a big dose of Western sensibility to his account of the Wild West shows,” the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote of The Colonel and Little Missy: Buffalo Bill, Annie Oakley and the Beginnings of Superstardom in America (2005), “but his efforts proved little more than a superficial glossing of Cody’s life.” Distinguished Texas writer Bryan Wooley wrote for The Dallas Morning News that McMurtry’s Oh What a Lovely Slaughter (2006) “doesn’t carry the reader much beyond generalization” and “its language is devoid of grace or power.”

Courtesy WireImage.com

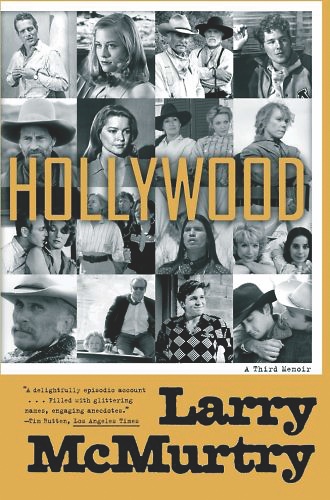

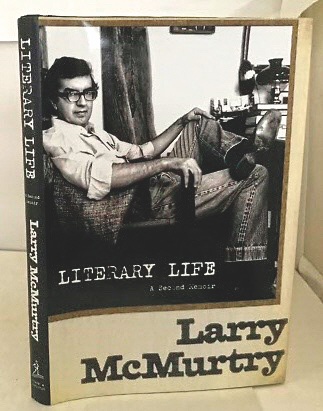

Yet McMurtry did what writers are supposed to do. He wrote. A lot. Often two to three books in a year. And while his fiction and historical nonfiction were often sloppy, his memoirs—Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen: Reflections at Sixty and Beyond (1999), Roads: Driving America’s Great Highways (2000), Books: A Memoir (2008), Literary Life: A Second Memoir (2009) and Hollywood: A Third Memoir (2010)— earned raves. He and writing partner Diana Ossana also won the Academy Award for adapting Proulx’s short story Brokeback Mountain into director Ang Lee’s 2000 film, which collected two other Oscars and was nominated for five more.

“Because of when and where I grew up, on the Great Plains just as the herding tradition was beginning to lose its vitality, I have been interested all my life in vanishing breeds,” McMurtry said.

McMurtry was a vanishing breed himself. “Live through it,” Woodrow Call says in Lonesome Dove. “That’s all we can do.” That could be McMurtry’s epitaph.

True West Archives

He might always be remembered for one novel, but his legacy goes beyond Lonesome Dove. For even in his worst books, McMurtry could still turn that perfect sentence that most of us could never dream of writing. And in his best works…well, here’s another fitting epitaph for Larry McMurtry, June 13, 1936–March 25, 2021, spoken by the Mexican cook, Po Campo, in…what else?…Lonesome Dove:

“I sing about life. I am happy, but life is sad.”

Johnny D. Boggs’s favorite Larry McMurtry line comes from In a Narrow Grave: “Only a rank degenerate would drive 1,500 miles across Texas without eating a chicken-fried steak.”

Must-Read McMurtry

Listed by year of publication.

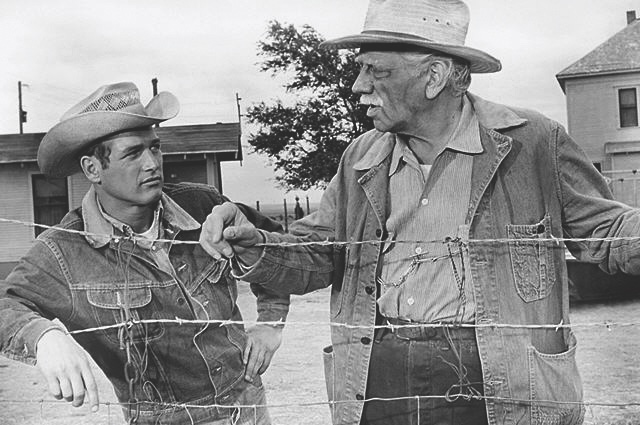

1. Horseman, Pass By (1961): In many ways, McMurtry’s first novel was his most earthy and realistic, told by Lonnie as he looks back on growing up during the 1950s Texas drought, pulled in a tug-of-war with his honest rancher grandfather and the freewheeling, nasty relative called Hud.

2. Leaving Cheyenne (1962): Told in first person by three Texans—rancher Gideon Fry, cowboy Johnny McCloud and Molly Taylor, the girl they both love—Leaving Cheyenne is another mix of comedy and tragedy. Marshall Sprague put it best in his New York Times review: “[I]f Chaucer were a Texan writing today, and only 27 years old, this is how he would have written and this is how he would have felt.”

3. The Last Picture Show (1963): A bleak, yet beautiful, portrait of a dying Texas town —Thalia is McMurtry’s thinly disguised Archer City—in the 1950s that includes arguably McMurtry’s most honest, memorable character, Sam the Lion. “Oh, [growing up] ain’t necessarily miserable,” Sam tells Sonny. “About eighty percent of the time, I guess.”

4. In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas (1968): “Before I was out of high school, I realized I was witnessing the dying way of life—the rural, pastoral way of life.” McMurtry’s homage to what it’s like to be a Texan.

5. All My Friends are Going to be Strangers (1972): The ups and downs of a writer’s life, told with pathos and laugh-out-loud humor, with cameos by dozens of richly developed characters. How many writers have wanted to drown their manuscript in a river?

6. Terms of Endearment (1975): Known for his believable female characters, McMurtry created two of his most memorable, dominating Aurora Greenway and her headstrong daughter, Emma. Don’t look for Jack Nicholson’s astronaut in the novel; Garrett Breedlove was producer-director-screenwriter James L. Brooks’s creation.

7. Lonesome Dove (1985): What else can be said about Gus, Call, Newt, Lorena, Clara, Jake, Blue Duck, Pea Eye, Deets, July, Roscoe, Dish and a memorable cast of hundreds? McMurtry set out to tear down the Western myth; instead, he revitalized interest in the Old West and reinvigorated Western literature.

8. Film Flam: Essays on Hollywood (1987): “If one were to make a misery graph of Hollywood,” writes McMurtry, no stranger to Hollywood, “screenwriters would mark high on the curve.” Anyone who ever thought about writing a screenplay should read this.

9. Roads: Driving America’s Great Highways (2000): Inspired by his well-traveled singer-songwriter son James’s words, “There’s just so much to see,” McMurtry sets out to rediscover America’s great highways. “I had no river to float on,” he writes of his childhood days on a landlocked Texas ranch. “Highway 281 was my river, its hidden reaches a mystery and an enticement.” For the road warriors in us all.

10. Books: A Memoir (2008): McMurtry details his love affair with books, not as a writer, but as a collector and dealer in rare books in Washington, D.C., Archer City and Tucson. This beautiful memoir strikes a chord with anyone who loves the written word.

–Johnny D. Boggs