Al Sieber & U.S. Troops vs. Na-ti-o-tish’s Apaches

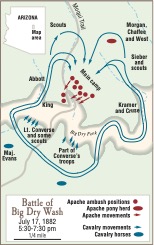

One of the scouts spots the Apaches waiting in ambush on the north side of the canyon.

July 17, 1882

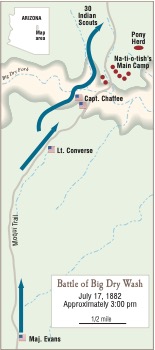

Apache leader Na-ti-o-tish (center) positions his warriors along a narrow gorge eight miles north of the Mogollon Rim in east central Arizona. They have built rifle pits and stacked rock wings adjacent to large pine trees, awaiting a small troop of soldiers (55 men) who will pass, single file on horseback, directly below them.

Stopping within three-quarters of a mile from the chasm, the first officer on the scene, Capt. Adna Chaffee, sends 30 scouts on foot to the west to get behind the canyon, as a precautionary move. The troopers and the remaining scouts move into a skirmish line along the south rim of the canyon. As they do, one of the Indian scouts discerns the hostiles’ position on the north side of Big Dry Fork. Captain Chaffee orders a feint to the center, then sends out two flanking movements: one to the west and one to the east of the Apaches’ position.

More troops arrive, but before any of them can get into position, a nervous “recruit lets his piece go [fires his weapon],” which opens up the fight. Both sides, some 700 yards apart, begin firing.

The westside flanking troops led by Capt. Lemuel Abbott run headlong into an Apache force attempting the same thing. Both sides open fire, and a hailstorm of lead fills the draw.

Chief of Scouts Al Sieber and his crew appear on the opposite rim just as the Abbott fight ensues. The Apache pony guards cock their heads toward the firing, and Sieber and another soldier “wipe them out.”

Scooping up the pony herd and stolen stock, Sieber and Lt. Thomas Cruse lead an assault into the rear of the hostiles’ position, firing as they run.

On the ridge, Lt. George Morgan, in his first major engagement with the Apaches, fires several times before finally hitting someone, yelling, “I got him! I got him!” as he exposes himself to enemy fire. An Apache bullet rips through his arm and into his body.

Hearing Sgt. Daniel Conn of Troop E shout orders to his troopers, some of the hostiles who had been scouts before the Cibecue fight (see time line, below) recognize his voice. He had served pork to them on ration day; they know him as “Hog Sergeant.”

The hostiles taunt him, yelling “Aaaaaiiah! Coche Sergeant!” Conn yells something back, and an Apache bullet hits the sergeant in the throat, “opening a hole as big as a silver dollar through a size-thirteen neck,” reports Lt. Thomas Cruse.

The day is expiring, and the shadows lengthen as various elements of the attacking troops form a line to push the Indians back toward the camp. Seeing this, Na-ti-o-tish harangues his men, ordering them to fight to the last man.

Lieutenant Cruse watches Sieber shoot and kill three renegades as they run toward the edge of the canyon. Sieber keeps on running and rolling, each time coming up firing. When Cruse calls up his men and attempts a charge into the Apache position, Sieber and Capt. Adam Kramer’s troops cover them with fire.

As Cruse advances, an Apache jumps up within two yards of the lieutenant and fires, just missing Cruse and hitting Pvt. Joseph McLernon, who falls mortally wounded. Cruse recovers and drags McLernon back to a ravine.

The hostiles make one more heroic attempt to break out to the north, but they are repulsed by the soldiers. As darkness envelopes the battlefield, a stalemate ensues, with the two sides less than 50 yards apart. A severe hailstorm sweeps across the rim, pelting and soaking everything and everybody. The dead are covered in an icy shroud, “four or five inches deep.”

The last major Apache battle on U.S. soil is over.

Apache Time Line

In the spring of 1881, Noch-ay-del-klinne (right), a White Mountain Apache medicine man, taught the Apaches a new dance. The performers arranged themselves like the spokes of a wheel, all facing inward, while the medicine man stood in the hub and sprinkled them with the sacred hoddentin (from the pollen of the tule) as they circled around him.

As Apaches flock to these dances, held near Cibecue, Arizona, reservation agents worry that Noch-ay-del-klinne is actually preaching to the others that their chiefs will return from the dead and the white man will disappear. To halt the medicine man’s influence, Joseph Capron Tiffany, the agent at the San Carlos Reservation, sends his Indian police to arrest the prophet, but they come back empty-handed, grumbling about white aggression. The enlisted scouts at Fort Apache demand passes to attend the dances, and they, too, return as converts.

August 14, 1881

Agent Tiffany sends a demand to Col. Eugene Asa Carr, the commander at Fort Apache: “I want [the Apache medicine man] arrested or killed or both.”

August 29, 1881

Colonel Carr sets out from Fort Apache with 117 men and 23 Apache scouts. Arriving late in the day in Cibecue, a 75-mile ride, Carr and his men arrest Noch-ay-del-klinne without incident, but his assembled converts follow Carr into camp, a mile from the arrest site. After several confrontations, a fight breaks out and Capt. Edward C. Hentig is shot point-blank in the heart, and is killed instantly.

A bugler of Troop D shoots the prophet three times in the head (Carr had threatened to kill him if there was any trouble). The Indian scouts defect. In the ensuing gunfight, eight soldiers and 18 Apaches are killed.

Vastly outnumbered, Carr and his command slip away by night and make it back to Fort Apache. Roving bands of Apaches sweep the area, killing soldiers and civilians wherever they find them.

Geronimo, living peacefully at San Carlos, is nervous. Twenty-two companies from California and New Mexico have descended on the reservation, where no soldiers have been on post since John Clum kicked them out in 1876.

A Tactical Bronco Blunder

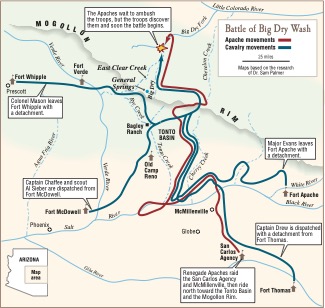

In the parlance of the times, Apaches who escape the San Carlos Reservation are called “Bronco Apaches.” Na-ti-o-tish, neither a chief nor a war leader, leads about 54 Bronco Apaches—including women and children—on a killing and raiding spree, no doubt angered by the death of their medicine man (see time line).

After plundering through Pleasant Valley for more than a week, they are about to turn east at the top of the Mogollon Rim and head back to the reservation when they spot pursuing troops at General Springs. They count 50 white horse troops on their trail.

What the Apaches fail to see are the numerous brown horse troops, some 200 men in all, coming up behind from four different forts (see above map).

Na’s warriors build rifle pits at General Springs, but for some reason, abandon them and travel eight more miles to Big Dry Wash to make their stand.

Some historians speculate that the Indians may have been drinking (liquor bottles are later found along the trail) and perhaps that leads to their miscalculating the strength of the U.S. troops.

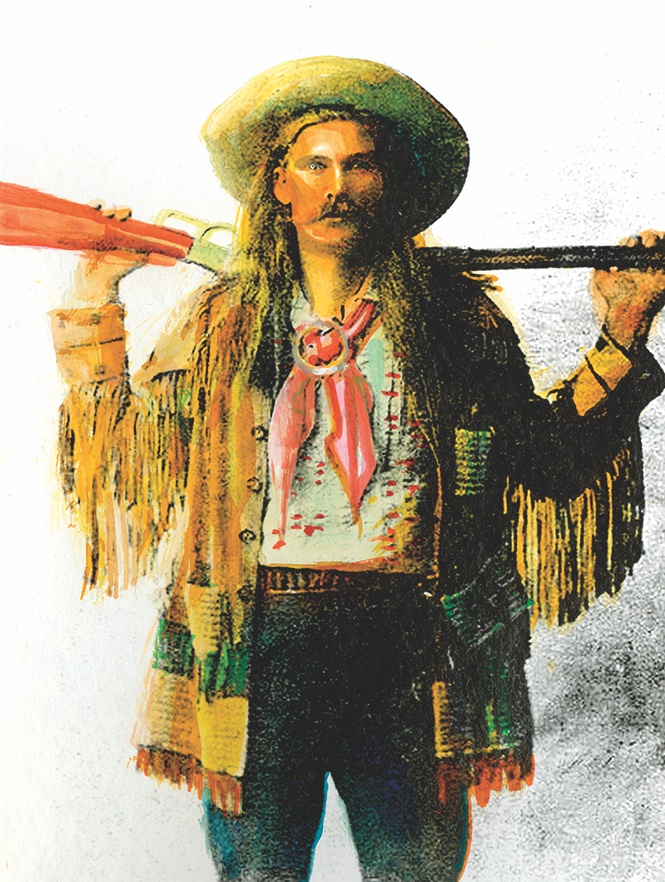

Arizona Charlie

Arizona is the home today of many famous people, but its first real superstar was a rodeo cowboy and Wild West performer named Charlie Meadows, better known as “Arizona Charlie.” In 1877, the Meadows family settled on a ranch at Diamond Valley, north of Payson, where the community of Whispering Pines is today.

In July 1882, Charlie had ridden to Pine Creek to guide an Army detachment through the pass at the head of the East Verde River onto the Mogollon Rim when a war party of Apaches swept through the Rim Country and attacked the Meadows ranch. His father and one of his brothers were killed and another was wounded in the ambush.

Following the raid, Na-ti-o-tish and his warriors headed up the Mogollon Rim for a place called Big Dry Wash.

Charlie was left in charge, and while caring for the family ranch in 1884, he, along with John Chilson, organized America’s first rodeo. Charlie won nearly every event, beating the famous Tom Horn in the roping contest. He went on the rodeo circuit and set new records in steer tying at Prescott. He won again in Phoenix. Show business was in his blood, and Charlie made up his mind to become a performer in a Wild West show.

—Marshall Trimble

“All the men performed their duty well. …It is no disoredth [sic] to the men to say that when they reached the top of the bluff, blowed and at pretty close quarters and heard the zip of bullets thick and hot they looked crosseyed for a few moments.”

—Captain Adna Chaffee

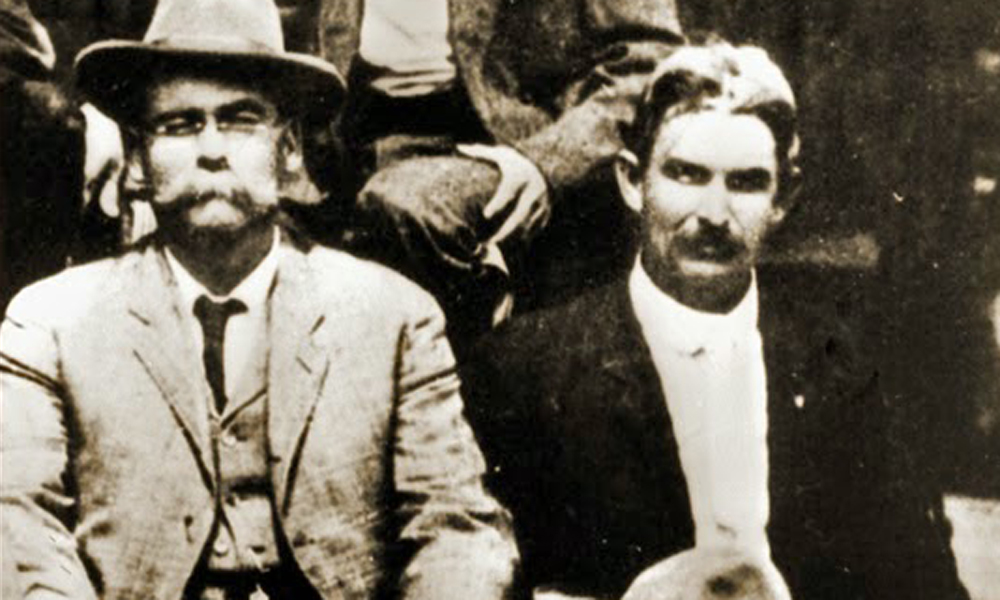

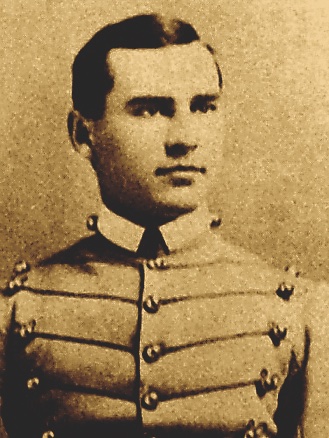

In El Paso, Texas, in October 1880, Lt. Charles B. Gatewood (center, large hat), civilian

scout Sam Bowman (behind Gatewood) and Lt. Thomas Cruse, (far left, tall crowned hat) posed after returning from the Victorio Campaign in Mexico. Cruse and many of these scouts fought at the Battle of Big Dry Wash. The young lieutenant, who would live until 1943, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his “distinguished conduct in battle.”

Courtesy National Archives

Al Sieber’s Deadly Efficiency

An immigrant from Germany, Sieber joined the Army just after his 18th birthday, fighting at Gettysburg with the First Minnesota. On the second day of the battle, he was severely wounded in a bayonet charge.

Ultimately discharged, he wandered West, landing in Prescott, Arizona, where he distinguished himself in several Indian fights. He rejoined the Army and rose to the rank of chief of scouts. He and his men just returned from killing 14 Apaches during the Tupper Battle (see time line) prior to the Big Dry Wash fight.

Describing the opinion of the time, Dan Thrapp, Sieber’s biographer, wrote, “Killing Indians was the dirty climax of the exciting sport of hunting them.” This sentiment applied to the Apache warrior side of the equation as well.

“Al Sieber took part in more Indian fights than Daniel Boone, Jim Bridger, and Kit Carson together. He shot more red adversaries than all of them combined.”

—Dan L. Thrapp, Al Sieber: Chief of Scouts

Many modern-day readers are puzzled and disturbed by the Apache scouts hunting their own people, but their warrior class, perhaps even more so than the “Americans,” loved the exciting sport of hunting. The “dirty climax” just came with the territory.

Before the Big Dry Wash fight, Maj. Andrew W. Evans and Lt. George Morgan’s scouts advised them that the hostiles were too far ahead. “Sieber, in his abrupt way, started them along pronto,” Morgan wrote.

Thrapp credited Sieber with dispatching almost half of the Apache casualties at Big Dry Wash.

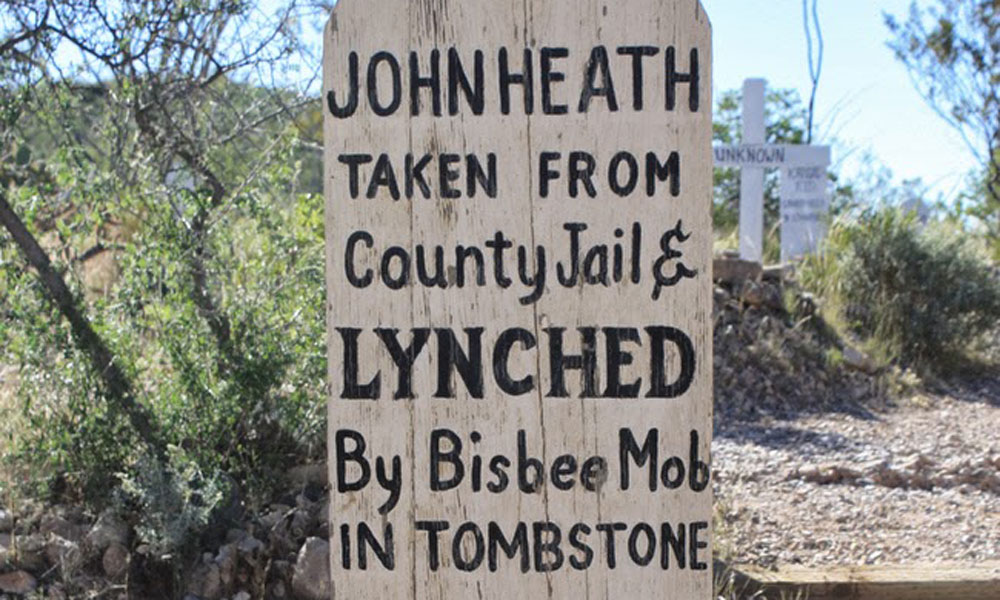

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Lieutenant George Morgan survived his wound, as “the slug had only gone around his ribs and lodged in the back muscles.” Sgt. Daniel Conn (“Hog Sergeant”) survived his throat wound, joking, “Sure, I heard the Cap’n say I was kilt, but I knew I was not. I was only speechless!” Pvt. Joseph McLernon died within an hour.

One of the Apache scouts, Pvt. Pete (Hoski-ta-go-lothe) was killed in the battle. An account, told years later by C.P. Wingfield, described that deadly day for Pete, who “saw two of his brothers and his father with the Indians. He threw his gun down and started to run to his folks. Sieber told him to halt. He did not heed him. Sieber raised his rifle and fired, shooting him in the back of the head.”

Shielded by the dark night, the hostiles stole away from their camp, leaving behind everything they owned, including “73 head of stock, 24 saddles, blankets, baskets, cooking utensils,” reported Capt. Adna Chaffee.

The morning after the battle, patrols scoured the area for the dead and wounded (accounts ranged from 16 to 22 dead bodies found). Lt. Frederick G. Hodgson and his men discovered a young Apache woman, badly wounded and shielding her baby, who fired on them three times. Troops captured her, amputating her shattered leg, which she endured without a murmur. She, along with her child, were transported back to Fort Apache where she recovered.

Recommended: Al Sieber: Chief of Scouts by Dan L. Thrapp, published by University of Oklahoma Press; Apache Days and After by Thomas Cruse, published by University of Nebraska Press.

Maps by Gus Walker

Based on the research of

Dr. Sam Palmer and Dan Thrapp

Four Medal of Honor Recipients for Big Dry Wash

The official citations read:

Thomas Cruse (July 12, 1892)

“Second Lieut. 6th US Cavalry—Gallantly charged hostile indians, and with his carbine compelled a party of them to keep under cover of their breastworks, thus being enabled to recover a severely wounded soldier.”

George Morgan (July 15, 1892)

“Second Lieut. 3rd US Cavalry—Gallantly held his ground at a critical moment and fired upon the advancing enemy (hostile indians) until he was disabled by a shot.”

Frank West (July 12, 1892)

“First Lieut. 6th US Cavalry—Rallied his command and led it in the advance against the enemy’s fortified position.”

Charles Taylor (Dec 16, 1882)

“First Sergeant Co. D 3rd US Cavalry—Gallantry in action.”