Old West adventures await across the Cowboy State’s colorful Carbon County

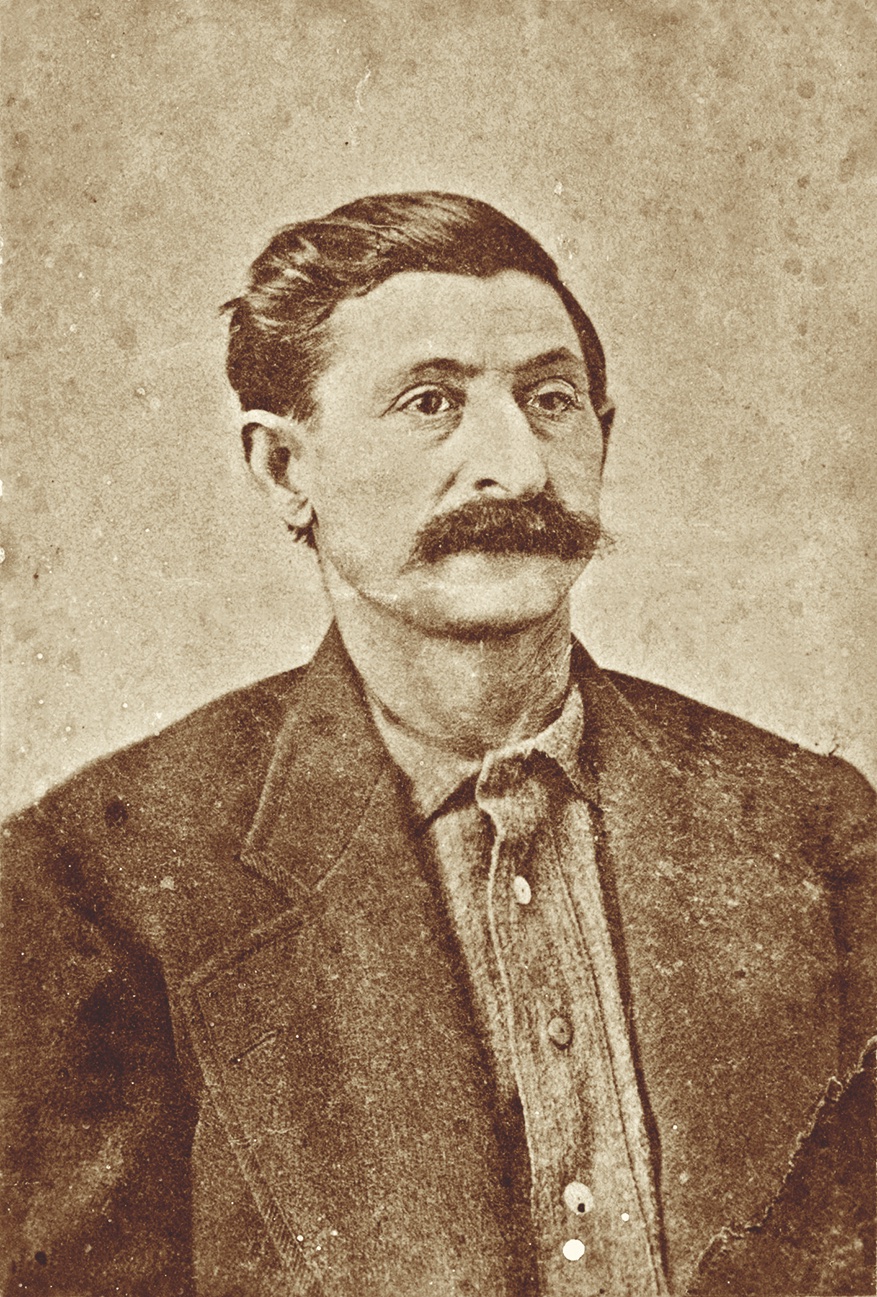

Quite likely the most gruesome artifact on exhibit in any museum in Wyoming (maybe the West) is the pair of shoes at the Carbon County Museum in Rawlins. They might appear to be just simple leather shoes, and they are…except that the leather is the skin of Big Nose George Parrott.

Photo by Candy Moulton

The skinning came after the hanging from a telegraph pole in front of the Hugus Store on Front Street in Rawlins…and that happened after Parrott hit Sheriff James G. Rankin over the head with a pair of shackles and then escaped from the county jail.

It all started in 1878 when Parrott, Dutch Charley Burris, and some accomplices attempted to derail a Union Pacific train near the coal mining town of Carbon. They weren’t successful, but the effort earned the attention of Carbon County Deputy Sheriffs Tip Vincent and Robert Widdowfield, who pursued the outlaws right into an ambush on the west side of Elk Mountain. Vincent and Widdowfield were the first two lawmen to die in the line of duty in Wyoming Territory, and after their killing, Parrott and Burris struck out north to Hole-in-the-Wall country and eventually to Montana, where they were arrested two years later.

Brought back to Carbon County, Burris was dragged off a train near Carbon and hanged. Parrott went to trial and was sentenced to death, but he escaped before his execution date. He was quickly recaptured and hanged and then skinned by the doctor who did the autopsy on his body. (There is more to his story that you can learn at the Carbon County Museum!)

Parrott was not the only outlaw to ride through Carbon County. Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch frequented the Little Snake River Valley, which was isolated and, more importantly, strategically located between Hole-in-the-Wall and Brown’s Park—both regular hangouts for the gang. The Gaddis-Matthews House in Baggs is a tangible reminder of the connections Cassidy and the Wild Bunch had to the area.

Big Nose George Parrott.

George Parrott photo courtesy True West Archives

Little Snake River

The oldest building at the Little Snake River Museum in Savery is a two-story hand-hewn log cabin built in 1873 by Jim Baker, an old mountain man with ties to the Shoshone tribe. The museum opened a new sheep industry exhibit in 2020 and has a number of other historic structures from ranches and homesteads. The museum holds regular history programs and annually hosts a trek to local historic sites.

Courtesy Little Snake River Museum

Kit Carson and John C. Fremont crossed the Sierra Madre between Savery and Encampment in 1843, and this region was filled with workers from 1896 to 1908, when the Grand Encampment Copper District swelled following the discovery of copper ore by Ed Haggarty, a sheepherder and prospector. Original buildings and artifacts from the mining camps, tie camps, the town of Grand Encampment and surrounding communities (many of them now ghost towns), are the foundation of the Grand Encampment Museum that has a one-room school, a two-story outhouse and a forest fire lookout tower. This year the museum hosts Bob Boze Bell in its True West History Symposium (June 11 and 12). Other speakers include Johnny D. Boggs, Linda Wommack and David Heska Wanbli Weiden.

Saratoga’s Hot Springs

Originally known as Warm Springs, Saratoga became a neutral area for tribes in the 19th century as they came to the area to soak in the natural hot mineral springs. Visitors still have a chance to enjoy the hot pools at the free Hobo Pool, located so close to the North Platte River that some who soak take a plunge into the cold river water as part of their “treatment,” just like the Indians used to do. Another hot springs soak is possible at the Saratoga Inn Resort in its medium-sized swimming pool and smaller soaking pools sheltered by Indian tipis.

Images Courtesy Saratoga/Platte Valley Chamber of Commerce

The Wolf Hotel in downtown Saratoga is a rare gem. It once changed ownership in a poker game, but the Campbell family bought it decades ago and restored it to Victorian grandeur. The rooms are uniquely decorated (one is now named for Joe Pickett, the Wyoming game warden created by local author C. J. Box), the bar is small and inviting, and the dining is among the best in the county.

Elk Mountain

The killing of Tip Vincent and Robert Widdowfield by Big Nose George Parrot and his associates took place on the west side of Elk Mountain. It took a sheriff’s search party nine days to find the two lawmen. Traveling today from Saratoga to Elk Mountain, take the Rattle Snake Pass Road which passes through the country where the lawmen met their end. This route was used by Cherokee Indians traveling to California after 1850, and it became a part of the Overland Trail.

In 1862, the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry established Fort Halleck, named for Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, as one of a series of forts/stations situated to protect the Overland Trail, which had replaced the more northerly Oregon-California trails as the major route linking East and West. Jack Slade worked for a time at Fort Halleck as the superintendent of the Overland stage line. The fort on the northside foothills of Elk Mountain was a tough assignment in winter due to deep snow and sometimes brutal winds.

While Elk Mountain is a very small town today, it has an excellent historic property—The Elk Mountain Hotel—where you’ll find a quiet room and a good meal. This town has ranch roots, but the nearby ghost town of Carbon was a mining and railroad town, the first coal town established on the Union Pacific Line in Wyoming. One early history says in 1869 the houses “sprang up as from the earth itself, as miners dug caves into the side of the nearby ravine and covered the fronts with board and earth, with a stovepipe poked through a hole in the top of each roof.”

More substantial homes and businesses quickly followed, and the Black Diamond newspaper dished the news of the camp. Miners flocked to the region to dig coal, producing an estimated 4.7 million tons from 1868 to 1902. There are multiple factors for the demise of Carbon. A cholera epidemic devastated many families, but the decision by the Union Pacific to move its main line farther north was the final blow. The new tracks spawned the coal-mining town of Hanna, and most people in Carbon moved there. (They even took some of the buildings with them.) The Hanna Basin Museum interprets the area’s coal-mining history, especially the tragic 1903 mine explosion that killed 171 miners.

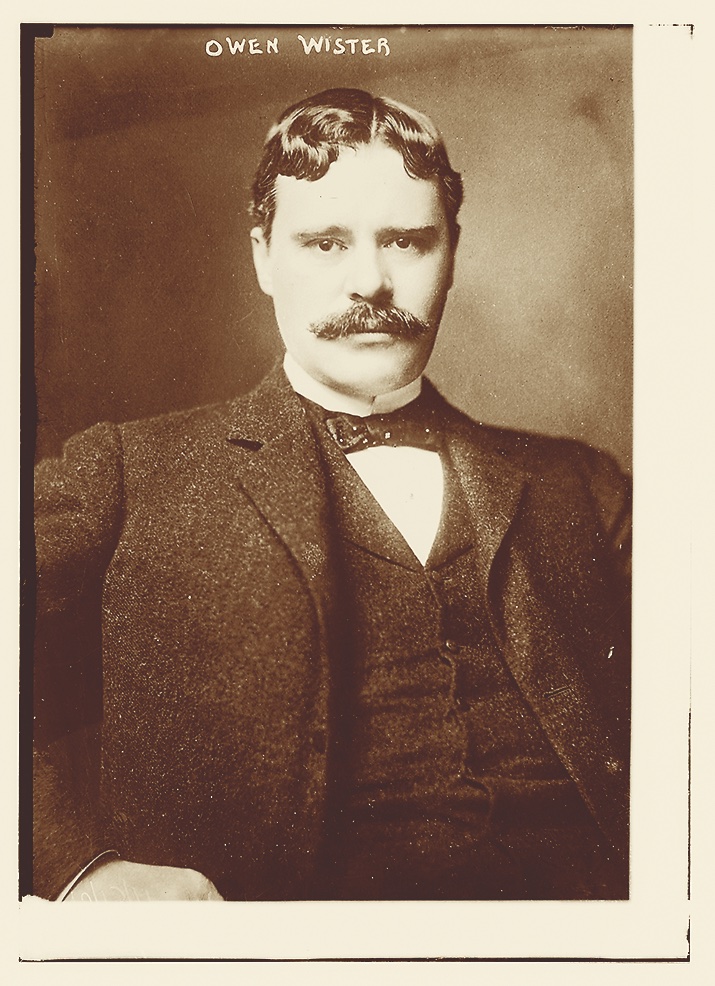

Photo of Owen Wister Courtesy Library of Congress/Photo of Virginian Hotel Bar by Candy Moulton

Medicine Bow

When Owen Wister visited Medicine Bow in 1885, he wrote in his journal a passage that later appeared almost verbatim in his classic novel The Virginian: “This place is called a town… Medicine Bow, Wyoming, consists of 1 depot house and baggage room, 1 Coal shooter, 1 water tank, 1 store, 2 eating houses, 1 Billiard hall, 6 Shanties, 8 Gents and Ladies Walks, 2 Tool houses, 1 Feed Stable, 5 Too late for classification, 29 Buildings in all.” When you visit today, you’ll see that the Bow is little changed.

Wister also said Medicine Bow appeared to be “Strewn there by the wind.” Yep! That still fits, so hold on to your hat.

Walking into the Virginian Hotel is like stepping back in time. The bar is almost a history exhibit with its collection of rodeo, ranching, cowboy and other historic photos on the walls, including a large original print of the Vern Wood photograph of the famous wild horse Desert Dust. A lunch counter and dining area with big booths are casual, but the Owen Wister Dining room is elegantly decorated in rich red with white linen, crystal and silver décor. The rooms in the main hotel include the Owen Wister Suite.

Union Pacific trains rumble routinely through the town (the tracks are across the street/U.S. Highway 30) from the Virginian. The former Union Pacific Depot has been converted into the town’s museum, which also has a UP caboose, and the small Owen Wister Cabin.

A Wide Spot in the Road

Fort Steele State Historic Site

In 1879, when Ute Indians revolted against the Indian agency managed by Nathan Meeker in northwest Colorado, perpetrating what became known as the Meeker Massacre, soldiers under the command of Maj. Thomas Thornburg rode from their post at Fort Steele to provide relief to the agency. Those troops encountered angry Utes and were themselves attacked in a battle that became a siege. Fort Steele was located adjacent to the North Platte River on a 36-square-mile military reservation with most buildings constructed of logs hauled in from Elk Mountain or floated down the North Platte River from camps in the Sierra Madre.

Fort Steele had adequate quarters for five companies of soldiers. Buildings also included a library, storehouse for the quartermaster and commissary, stables, shops for carpenters, a blacksmith, bakery, a granary and an area for laundresses. Once the Union Pacific Railroad was in place, the fort was a strategic supply location. Foundations and crumbling ruins of some of the buildings remain at the state historic site, located just off Interstate 80 east of Sinclair.

Good Eats and Sleeps

Good Grub: Su Casa, Sinclair; West End Café, Rawlins; Buck’s Sports Grill, Rawlins; Cowboy Inn, Baggs; The Divide, Encampment; Hotel Wolf, Saratoga; Bella’s Bistro, Saratoga; Saratoga Sandwich Shop, Saratoga

Good Lodging: Spirit West River Lodge, Encampment; Hotel Wolf, Saratoga; Saratoga Inn Resort, Saratoga; Elk Mountain Hotel, Elk Mountain; Virginian Hotel, Medicine Bow; Best Western Cotton Tree, Rawlins