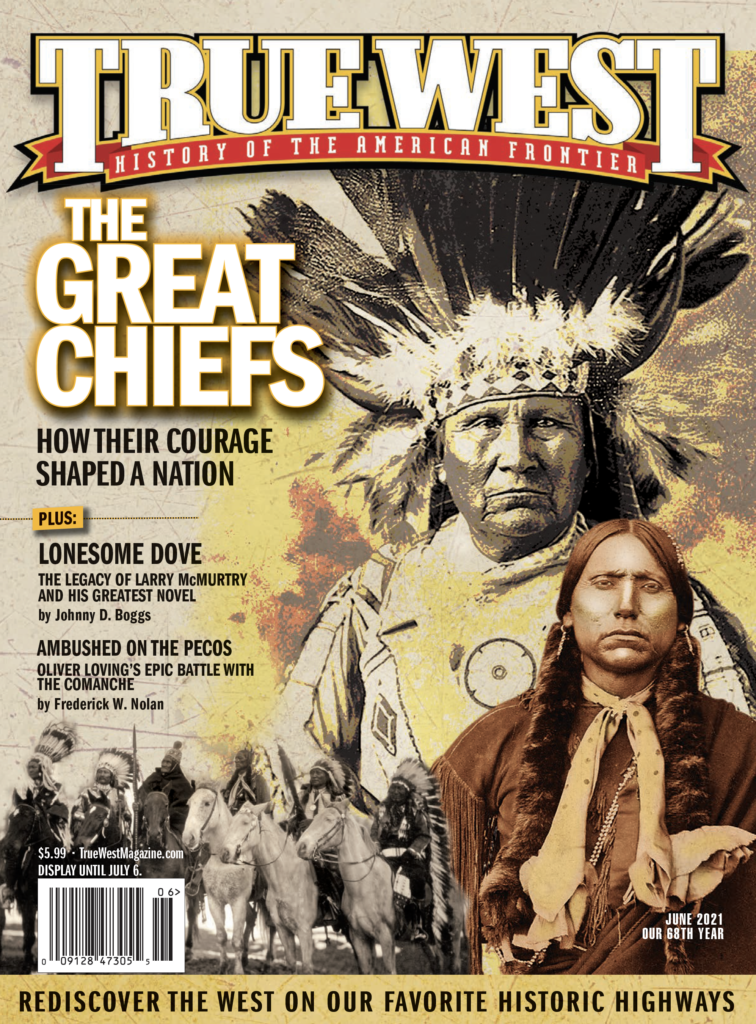

Their Courage Shaped a Nation

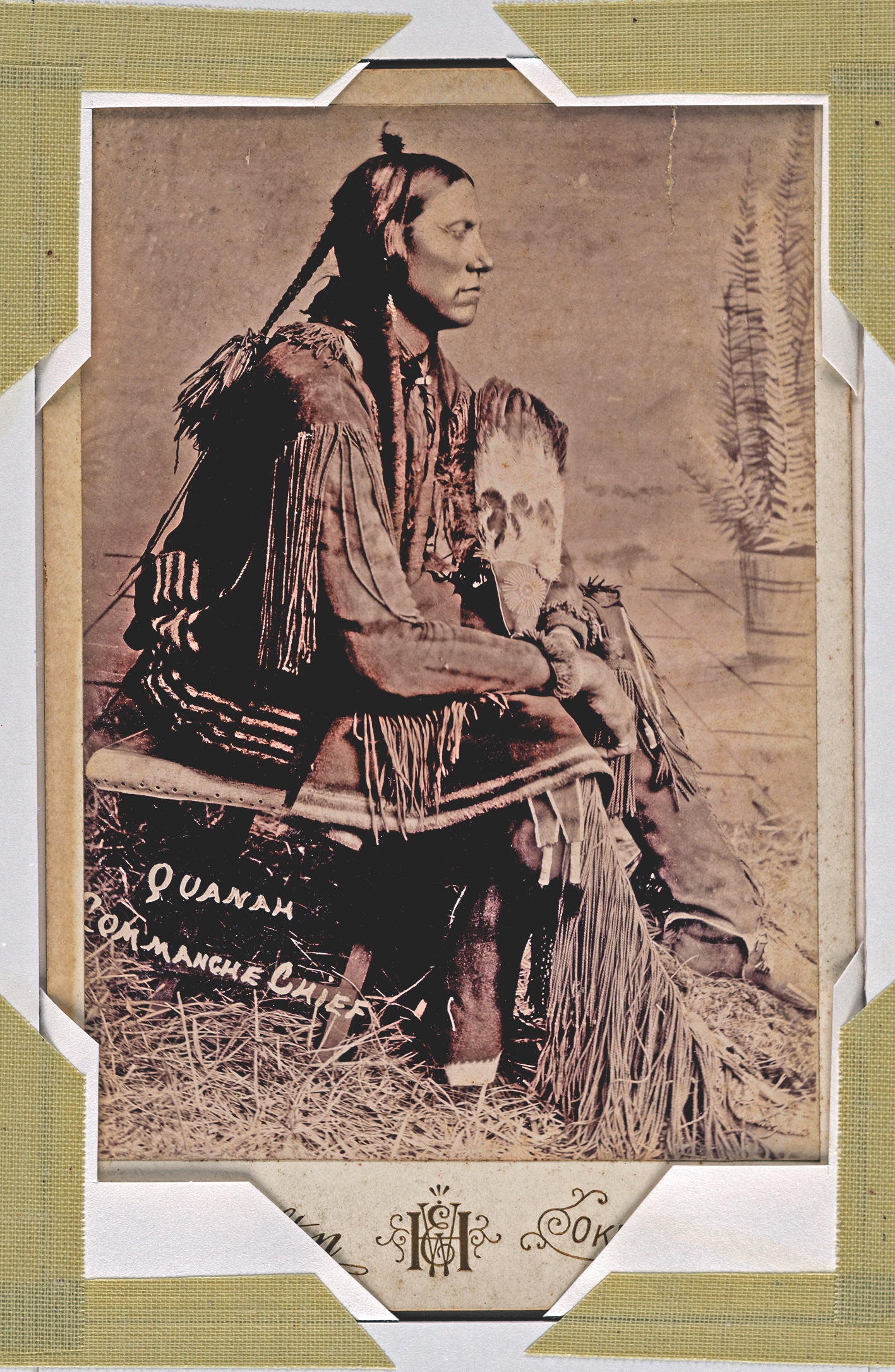

“Resting here until day breaks and shadows fall and darkness disappears is Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Comanches” – Epitaph on Quanah Parker’s gravestone

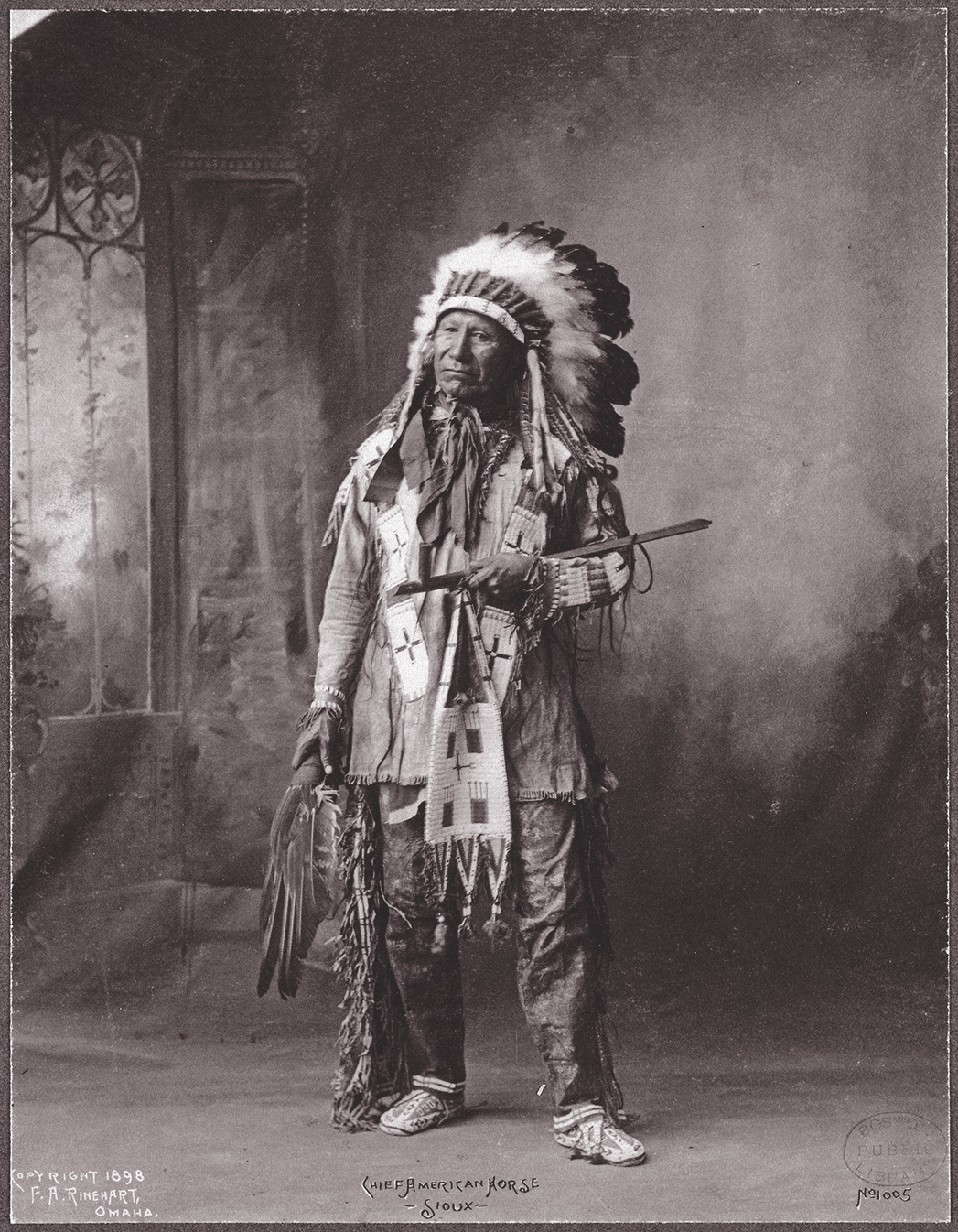

On March 4, 1905, Comanche Chief Quanah Parker paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue in President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade. With him in the parade of 35,000 were five other Indian leaders: Geronimo, Little Plume, American Horse, Hollow Horn Bear and Buckskin Charlie, representing the Apache, Blackfeet, Oglala, Brulé and Ute people, respectively.

Despite criticism from politicians and the press that six Indian leaders who once fought against the United States would be in the parade, the befeathered leaders rode with dignity and pride, and were greeted along the parade route with applause.

Courtesy Library of Congress

According to the Baltimore Sun, when “Old Quanah Parker, who was nearest the President’s Stand, rose in his stirrups and shot his glance at the President in salutation,” Roosevelt heartily applauded and waved his hat in return. And marching right behind them were the cadets of the Carlisle Indian School. It seemed to all those optimistic about the future, that a new era was about to begin for Indians in America.

More than 115 years later, Roosevelt’s inaugural parade remains symbolic of the enigmatic relationship between the United States and its Indian citizens and leaders. The parade took place just 15 years after the Massacre at Wounded Knee, less than 20 years after Geronimo surrendered and 30 since Quanah Parker and the Comanches had surrendered to the reservation after the Red River War. The majority of American Indians in 1905 were relegated to reservation life and “Americanization.” And for most of them, it was still a time “in-between”: the old life remained a strong memory, but the reality of the present and future meant greater change and adaptation to modern American life.

Yet most historians agree that the fate of the nation’s Indian tribes could have been far worse if not for the courageous and valiant leadership of the tribal chiefs. Many Indian leaders fought and died for their people without ever enjoying the benefit of peace, while other chiefs led the way, first in war and then in peace, to ensure a future for their people.

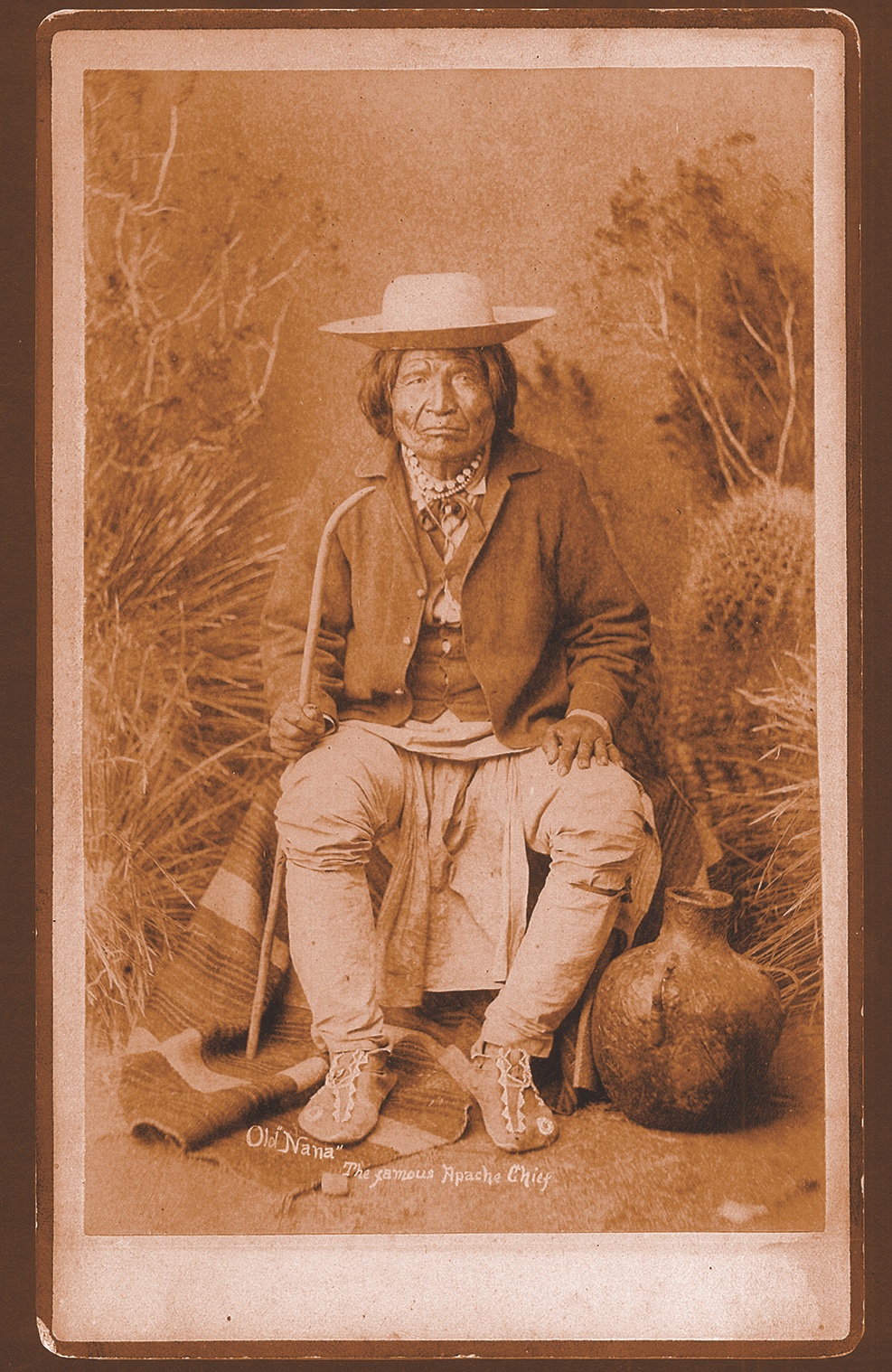

True West Archives

We have asked four historians to write about eight of these men and their roles in shaping our nation and their tribal histories. Of course, many other leaders could be profiled, including those we do not have photos of—Crazy Horse, Cochise, Victorio and Mangas Coloradas.

Without the great chiefs—whose skillful tactics and unfettered determination protected their tribal lifeways—it is unknown what the fate of the American Indian people would have been. We honor them today and forever because we know that their courage and leadership helped to shape a nation, yesterday and today.

—Stuart Rosebrook

Sitting Bull

The Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and patriot never wavered in his fight for the traditions and rights of his tribe.

The charismatic Hunkpapa Lakota Sitting Bull (1831-1890) is rightly remembered as the Indian most responsible for wiping out Custer. That was, after all, his village at the Little Bighorn, and in the minds of most Americans, that great Indian war of 1876-77 was Sitting Bull’s War, as he was the traditionalist most unwilling to surrender the northern plains to railroaders and settlement. Any deeper look only leads to the truths of those bold statements.

Like most Lakotas, Sitting Bull was first a prominent warrior, his early successes against enemies earning much acclaim. But through most of his adult life he was foremost a holy man, a spiritualist who repeatedly sacrificed himself in the Sun Dance and prayed and dreamed, always for the well-being of his people, and most memorably on the eve of the battles of the Rosebud and Greasy Grass.

Sitting Bull could also bedevil his detractors. In the long wake of the Little Bighorn, he defied repeated pleas to surrender, hating the word surrender itself and often repeating that he was never at war with the whites but only defending himself in his own country. All he wanted, he declared, was to be left alone to hunt buffalo.

Even after surrendering and returning to the United States from Canada, Sitting Bull never surrendered his traditional values. He barely tolerated reservation life, shunned whites with few exceptions—Mounted Police Officer James Walsh and showman Buffalo Bill among them—and embraced the hope of the Ghost Dance, which ultimately led to his death in a botched arrest aiming to remove his powerful influence from the Standing Rock Reservation.

Today, a college awarding associate’s, bachelor’s and master’s degrees is named for this greatest of all Lakota traditionalists.

—Paul L. Hedren

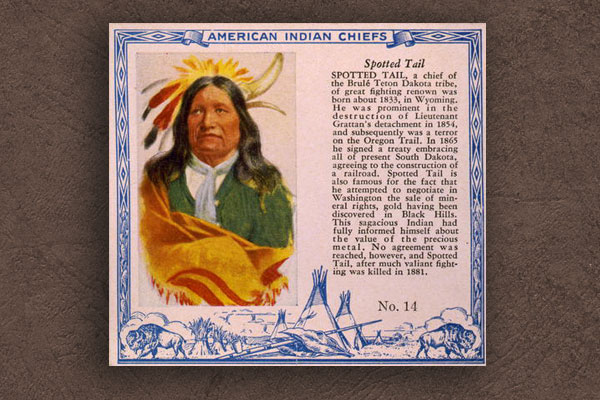

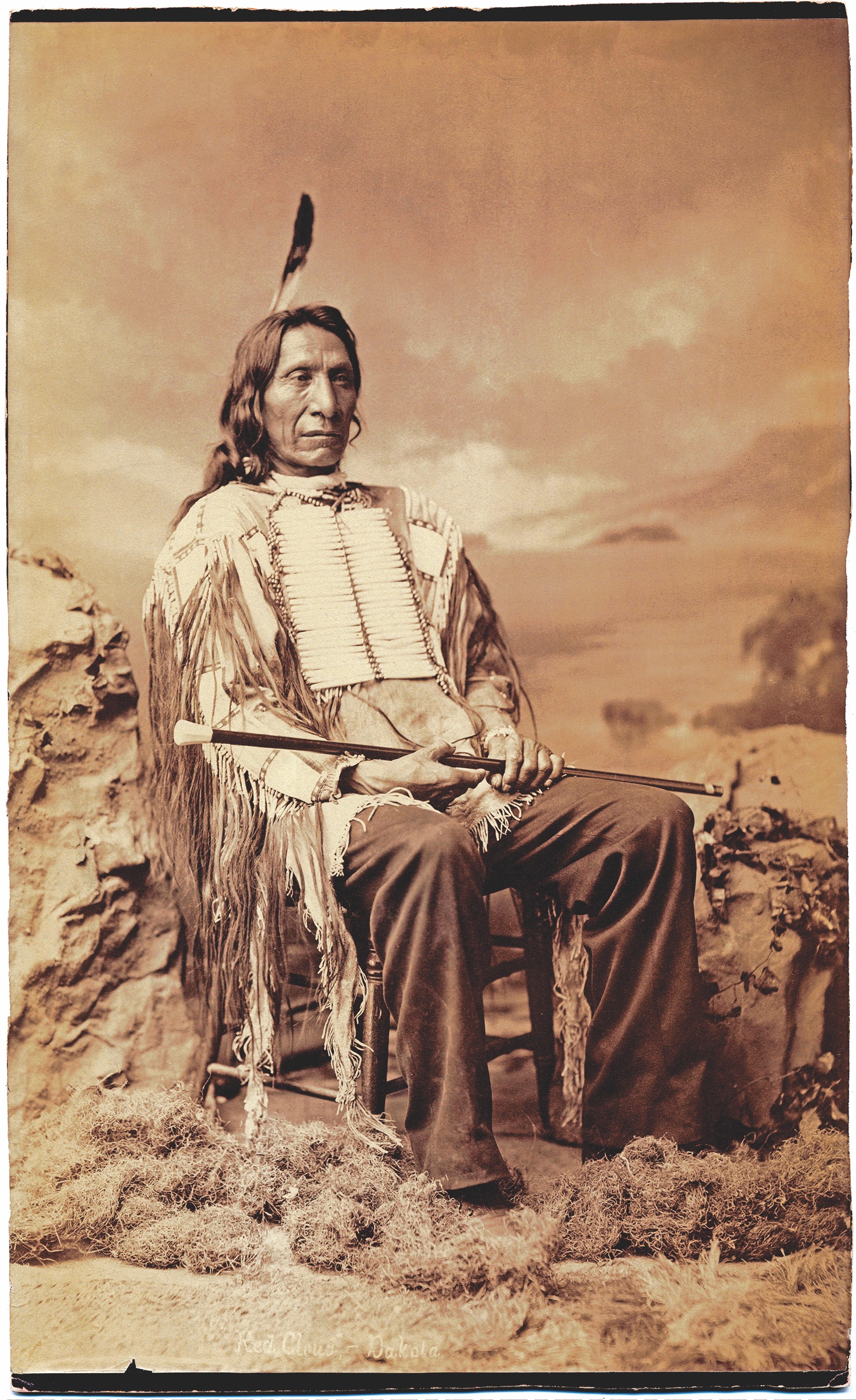

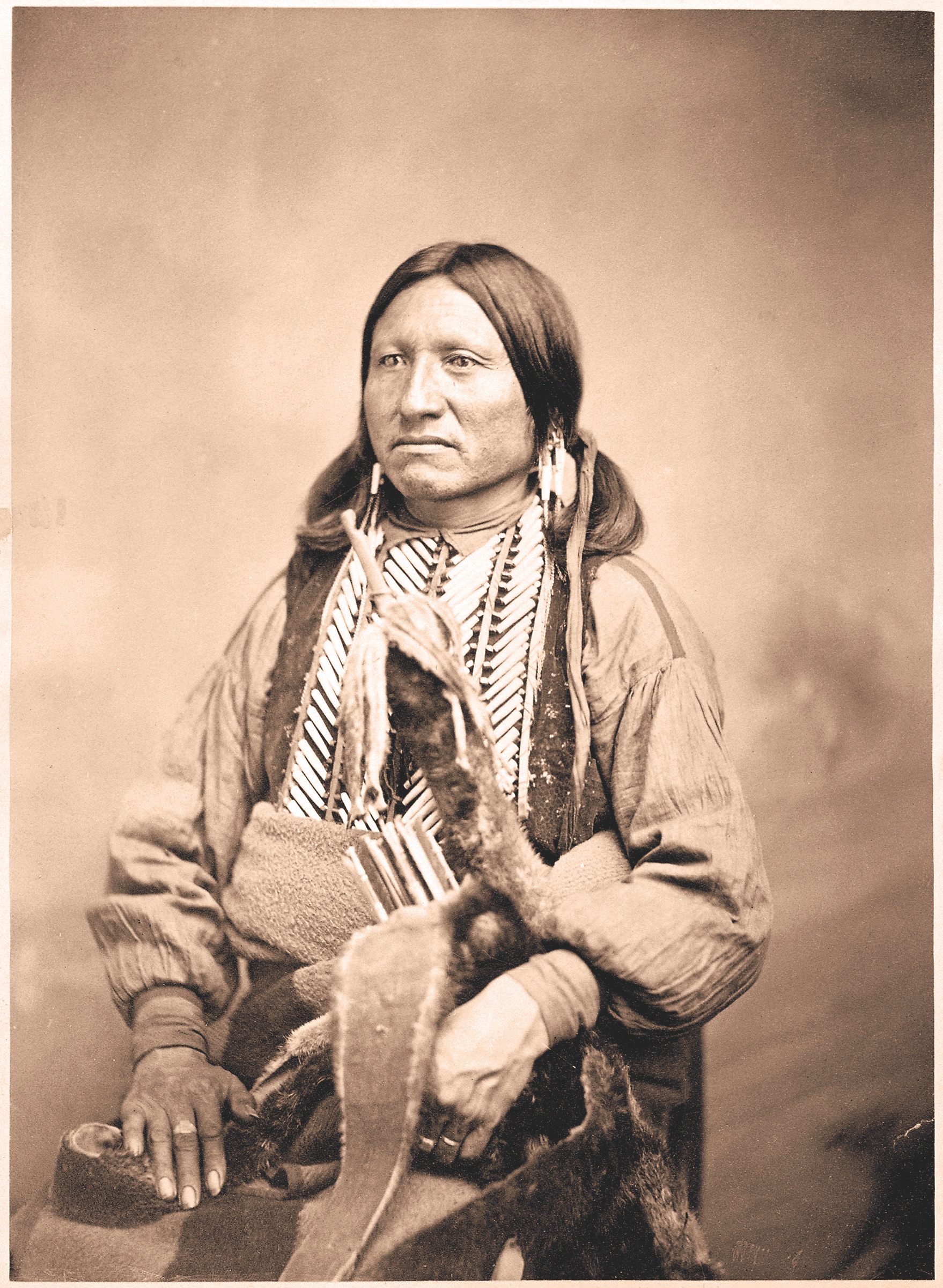

Red Cloud

The Lakota chief valiantly defended his land and his people in war and peace.

Like many great 19th-century Lakotas, Red Cloud (Oglala, 1821-1909) led a complex life partly in the free and unconstrained days of the buffalo prairie, warring on tribal enemies and leading in the defense against an emigrant tide swallowing his homeland. But Red Cloud’s long journey played out as well in the tumultuous era of reservation confinement, the Ghost Dance and culturally destructive white control.

Foremost, Red Cloud’s reputation is grounded in the early defense of the Lakota homeland, particularly when whites dared traverse a gold rush trail slicing straight through the Powder River buffalo country of Wyoming and Montana. We rightly remember the resulting conflict as Red Cloud’s War, reflecting his stalwart resistance to the forts and soldiers futilely attempting to secure that road, and his unwillingness to the last to sign a treaty ending that war until personally witnessing the abandonment of the hated road and its forts.

Red Cloud’s legacy in the early reservation era is equally compelling if sadly less appreciated. He traveled often to Washington and knew Presidents personally. He grasped the enormity of the white culture enveloping his own, all the while steadfastly embracing Lakota values and traditions, becoming a pragmatic voice for his people and a tireless advocate for their welfare and betterment.

Red Cloud, renowned as the most often photographed Indian in America, outlived his other great Lakota contemporaries and to the last stayed true to his people, giving his all to lead them through the difficult days.

Today, no massive granite monument is carved in Red Cloud’s honor, and we can only wonder why.

—Paul L. Hedren

Paul L. Hedren of Omaha, Nebraska, is a historian of the Northern Plains and its Indian wars. His most recent books include Powder River (2016), Rosebud, June 17, 1876 (2019) and John Finerty Reports the Sioux War [editor] (2020).

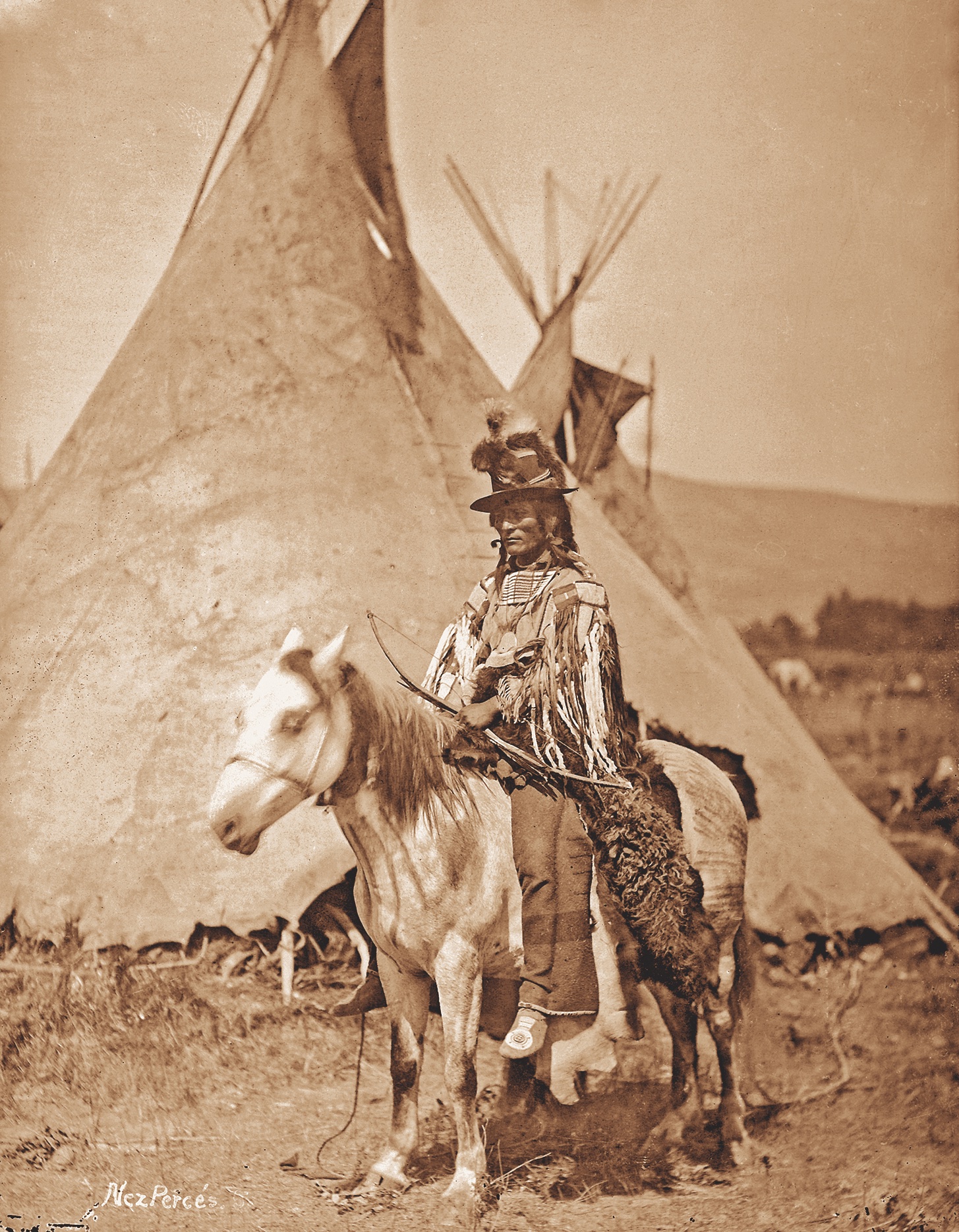

Looking Glass

The Nez Perce war chief led his people with honor and pride.

Looking Glass, born in 1832, was a war chief and spokesman for some 40 families. They lived on the newly established reservation in 1877. But without provocation Army Gen. Oliver O. Howard ordered Capt. Stephen G. Whipple to “surprise and capture this chief and all that belonged to him.”

After the attack, Looking Glass joined with Chief Joseph and others. He had vast knowledge of fighting techniques, the lands of the Nez Perce and the buffalo country to the east. He provided primary war chief leadership for the tribe as they fled across the Lolo Trail and up the Bitterroot Valley. When soldiers located the Nez Perce camp at the Big Hole, Looking Glass organized the defense while Chief Joseph guided the families away

Following that battle, Lean Elk assumed leadership command of the tribal groups, staying in charge as they traveled through Idaho, Yellowstone National Park and across Montana heading north to Canada. Lean Elk’s rigid schedule became wearing and Looking Glass again assumed primary leadership. Almost immediately the travel pace slowed. Despite disagreement among the headmen, the people complied with Looking Glass’s order to make camp on Snake Creek at noon on September 29. They were just 40 miles from Canada when the Army surrounded them. Joseph counseled surrender, but Looking Glass said he never would. While standing to look over the battlefield, he was shot. Looking Glass was the last Nez Perce fighter to die at the Bear’s Paw battle.

—Candy Moulton

Chief Joseph

The Nez Perce leader was a peacemaker, a diplomat and tireless activist for Indian rights.

With the words “I will fight no more forever” Chief Joseph put an end to a 1,500-mile flight of the Nez Perce tribal bands who had refused to abide by an 1877 treaty and move onto a reservation in Idaho. For years he was revered as the great chief of the Nez Perce War. In reality, Joseph was a headman who always advocated for cooperation and peace with the Army and encroaching whites. Born in the Wallowa Valley of Oregon, he accompanied his father (also called Chief Joseph) to the 1855 treaty council, sitting behind the older men and learning the techniques of Indian diplomacy.

By 1877, he was the recognized leader of the Wallowa band. At the treaty council that year he joined other headmen in efforts to remain in their homelands. But they were ordered onto the reservation in Idaho. Instead, they fled. Joseph’s role during the five-month flight was as a leader of the families, a protector of the young and the old. The fighting men were commanded by others, including his brother Ollokot, White Bird, Toohoolhoolzote, Lean Elk and Looking Glass.

Finally, surrounded and under siege at the Bear’s Paw Battle, and with concern for the families foremost in his mind, Chief Joseph surrendered to Gen. Nelson Miles. All the other headmen had been killed or escaped to Canada with White Bird.

Removed to Indian Territory, Chief Joseph utilized political forums and enlisted the aid of Indian rights groups to win approval for the Nez Perce to return to the Pacific Northwest. Joseph and his closest band members were relocated to the Colville Reservation in Washington.

—Candy Moulton

Candy Moulton is the author of the Spur Award-winning biography Chief Joseph: Guardian of the People, and a lifetime member of the Nez Perce Trail Association.

Quanah Parker

In war and peace, the Comanche leader valiantly fought for his people’s rights.

Quanah Parker was a giant among American Indians, a man with ties to both the white and Indian worlds. He strode through different eras, from the American pioneer period to the modernization of the 20th century. He was a successful rancher and businessman with a showcase house that still stands.

Pretty good for a man whose name means “smell.”

Quanah was born in around 1845 in what became southwestern Oklahoma. His father was the great Comanche warrior Peta Nocona. His mother was Cynthia Ann Parker, a white girl taken captive by the Comanches in the 1830s. As he grew up, Quanah built a reputation as an able hunter and warrior, a worthy successor to his father and a true Comanche. In the 1860s, when many tribal chiefs talked peace with the whites, Quanah Parker spoke only of war.

He had the chance to back up his words in 1874 when he led an estimated 700 warriors against a small group of buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls in Texas. The whites managed to hold off the attack; when Quanah was wounded, the battle came to an end.

The next year, Quanah Parker led his people on to the reservation—and showed even greater leadership. Named chief by the U.S. government, he embraced ranching and business. He advocated for education for Indian youth. He was one of the founders of the Native American Church, a mix of Christianity and traditional beliefs. He became friends with many whites, including President Theodore Roosevelt. And when he died in 1916, Quanah Parker was one of the most respected Indians in the U.S.

—Mark Boardman

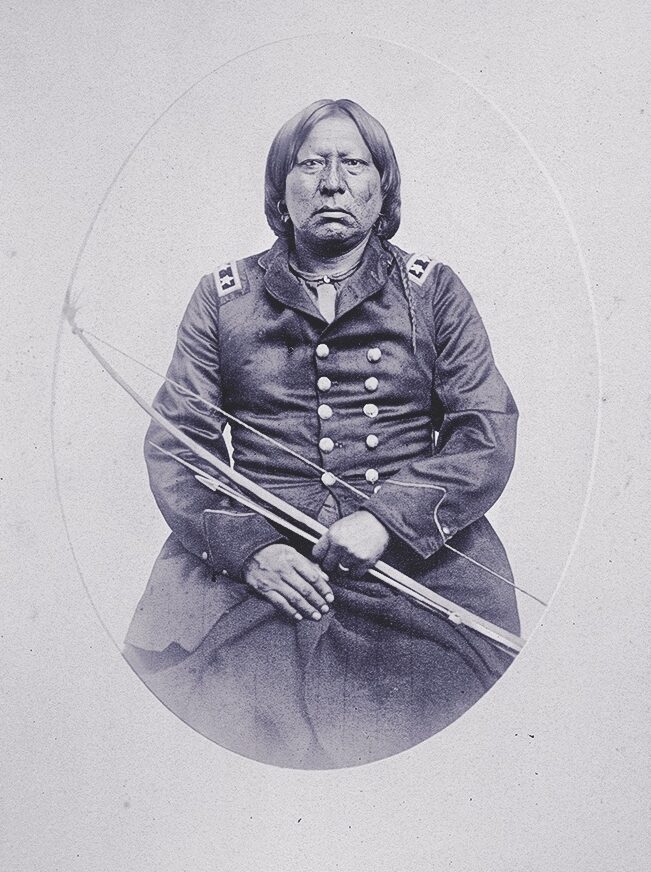

Kicking Bird

The Kiowa leader fought against all odds for his tribe before his tragic death.

His name may not be as well-known as those of some Indian figures, but over a decade or so, Kicking Bird was one of the most important leaders in the Texas Panhandle, western Oklahoma and southwestern Kansas. And his efforts in war were eclipsed by his work for peace.

Kicking Bird was of Crow and Kiowa ancestry, born around 1835. His name—which also translates as Striking Eagle—was an indication of his fighting prowess. With other Kiowa warriors, he battled other Southern Plains tribes through the early 1860s. Perhaps it was inevitable that they would turn their attention to the migrating whites. Kicking Bird fought in the First Battle of Adobe Walls in 1864.

By 1865, he’d become a sub-chief of the Kiowas and was convinced that peace was the only way for his people to survive. And outside of one incident in 1870 (the Battle of Little Wichita River), he worked for that peace for the rest of his life. He was also a great proponent of education for Kiowa children.

But Kicking Bird’s work for peace made him many enemies among his own tribe. Even when he became head chief in 1875, several bands wanted to fight the whites. The reservations provided terrible conditions and destroyed the old culture.

On May 3, 1875, at Fort Sill, Kicking Bird died mysteriously after drinking a cup of coffee. Many believed he’d been poisoned. Others thought a medicine man had killed him with a hex. But he had laid the foundation for the Kiowa people to find peace with the United States.

—Mark Boardman

Mark Boardman is Features Editor at True West, Editor of The Tombstone Epitaph, and pastor at Poplar Grove United Methodist Church in Indiana.

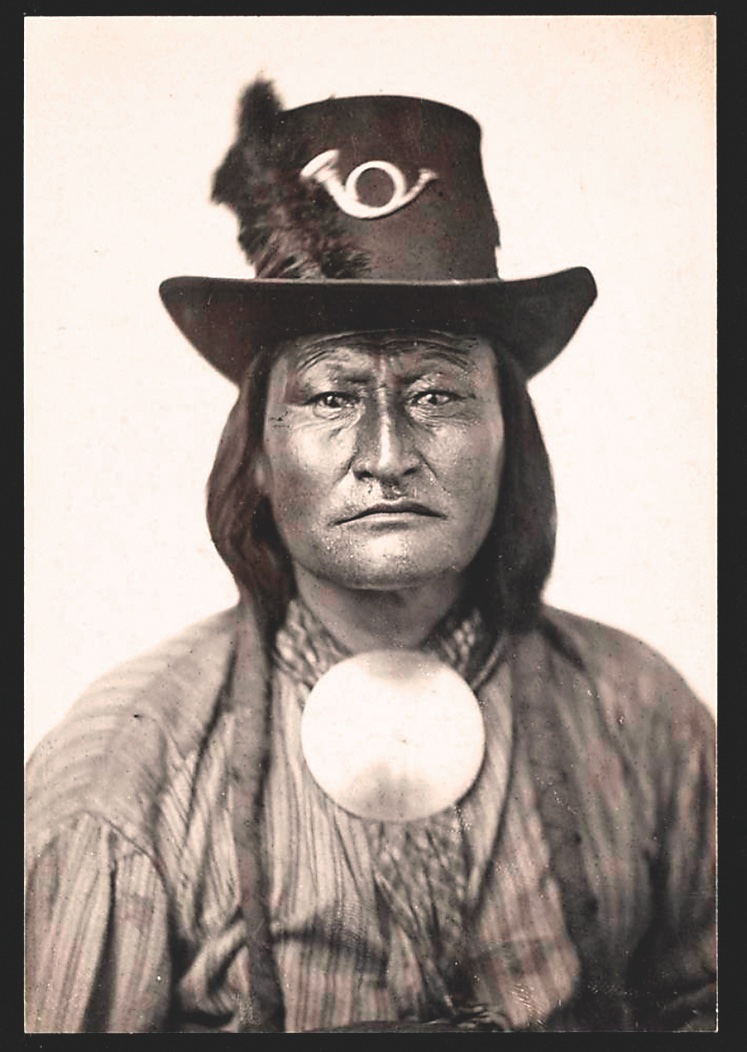

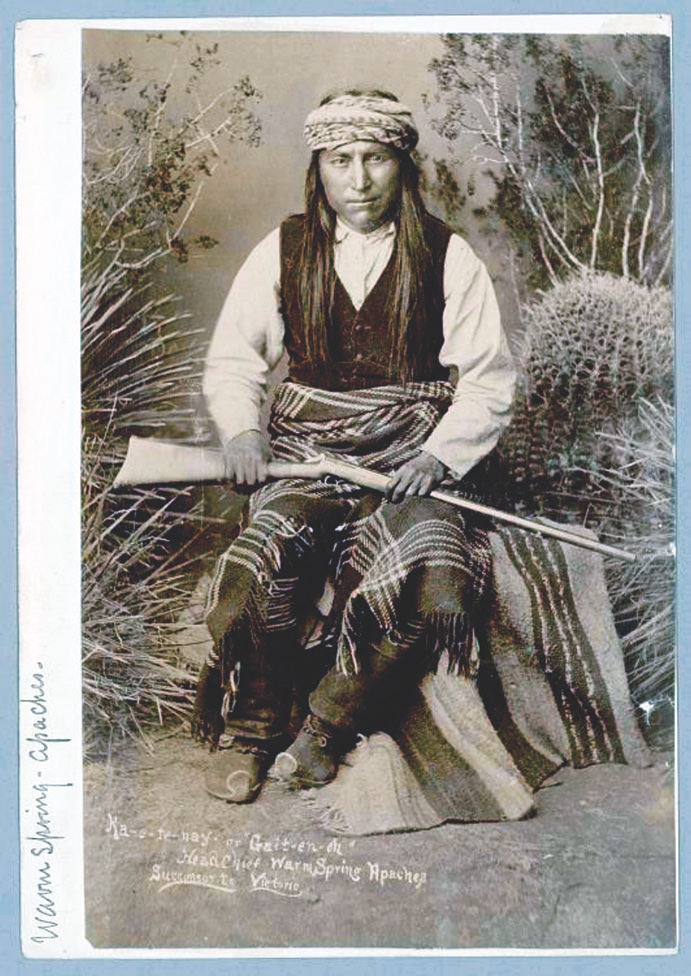

Naiche

The Chiricahua chief valiantly fought for his people in war and peace.

In his memoir, The Names, N. Scott Momaday wrote about his father who moved out of the old world of the Kiowas to make a life for himself: “I know now that this was an act, not of renunciation, but of profound affirmation, and that it required considerable courage and strength.” This viewpoint is also apropos to Naiche, grandson of Mangas Coloradas and youngest son of Cochise.

Naiche became the chief of the Chokonen Chiricahuas in 1876 at the age of 19 after his brother, Taza, who Cochise had groomed to be chief, died from pneumonia. Naiche knew he was not prepared to lead his People. He had no supernatural warfighting powers like Geronimo and soon made Geronimo his di-yen (medicine man), his consiglieri and his war chief. Geronimo often appeared to be the leader of the two, but whenever there was any question of authority, Geronimo always made it clear that Naiche was chief.

After their surrender to General Miles in 1886 and subsequent exile to POW camps first in Florida, then Alabama and finally Oklahoma, Naiche led the Chiricahuas away from their former lifeway of fighting and raiding. He led them, like himself, to “live like white people in a home; keep my clothes clean, keep myself clean, and be a man…think good [and] act good.” At the same time, Naiche fought the bureaucracy to keep Chiricahua tribal culture intact and to push for its just due in a good place to live.

—W. Michael Farmer

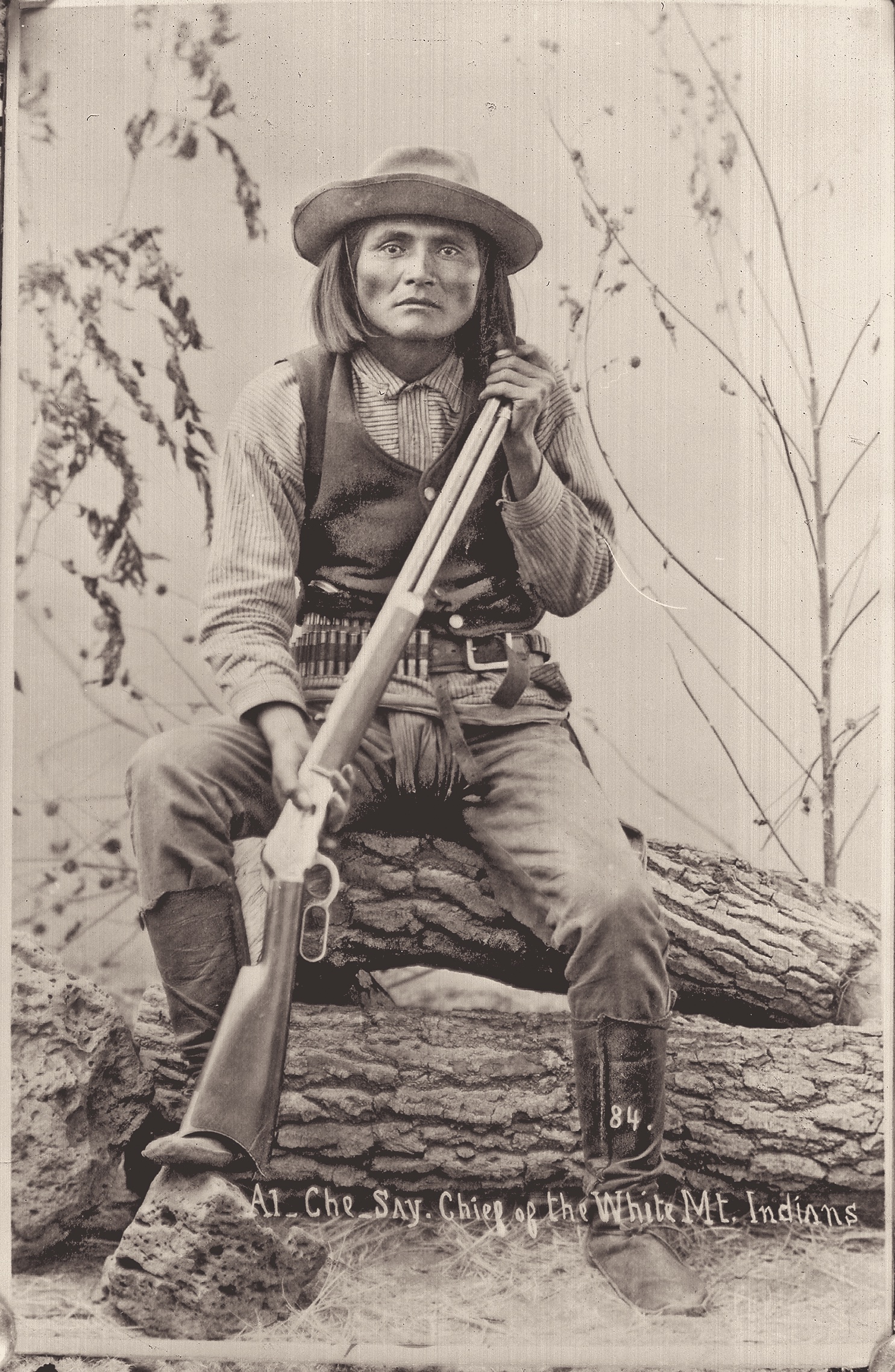

Alchesay

The Apache chief stood alone in his indomitable dedication to peace for his people.

The courage of Alchesay, nephew of the White Mountain Apache chief, Pedro, showed many facets reflecting his roles as warrior, chief or diplomat.

At 18, Alchesay, the warrior, became a member of Gen. George Crook’s scouts and fought in the 1872-73 Tonto War. He was a superb scout who knew the land and people and showed great courage under fire, which was followed and noted by his commander. Alchesay and nine other scouts were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1875.

Noch-ay-del-klinne, the Cibecue Apache ghost dance prophet, was killed in 1881 when his people tried to free him from arrest by Col. Eugene Asa Carr. As a sergeant of scouts, Alchesay courageously spoke up against the arrest disaster and was jailed for fighting against the Army but released for lack of evidence. In 1883, he, with other sergeants, helped General Crook lead nearly 200 scouts into Mexico and returned the Chiricahua Apaches to San Carlos. The nearly bloodless Chiricahua return was the beginning of the end of the Apache Wars.

Alchesay became the leading White Mountain chief in 1884 and helped the returning Chiricahuas establish their farms on Turkey Creek near Fort Apache. Geronimo led an escape from the reservation in May 1885. Alchesay played a key role in helping General Crook talk most of the Chiricahuas into surrender in late March 1886.

As a chief, Alchesay met and advised Presidents Cleveland (1887), Roosevelt (1909), and Harding (1921) to push for better living conditions for his People.

—W. Michael Farmer

W. Michael Farmer of Smithfield, Virginia, is a Western historian and novelist. His most recent books are True Stories of Apache Culture 1860-1920 (2018), Geronimo: Prisoner of Lies: Twenty-Three Years as a Prisoner of War, 1886-1909 (2019) and The Odyssey of Geronimo: Twenty-Three Years a Prisoner of War, A Novel (2020).

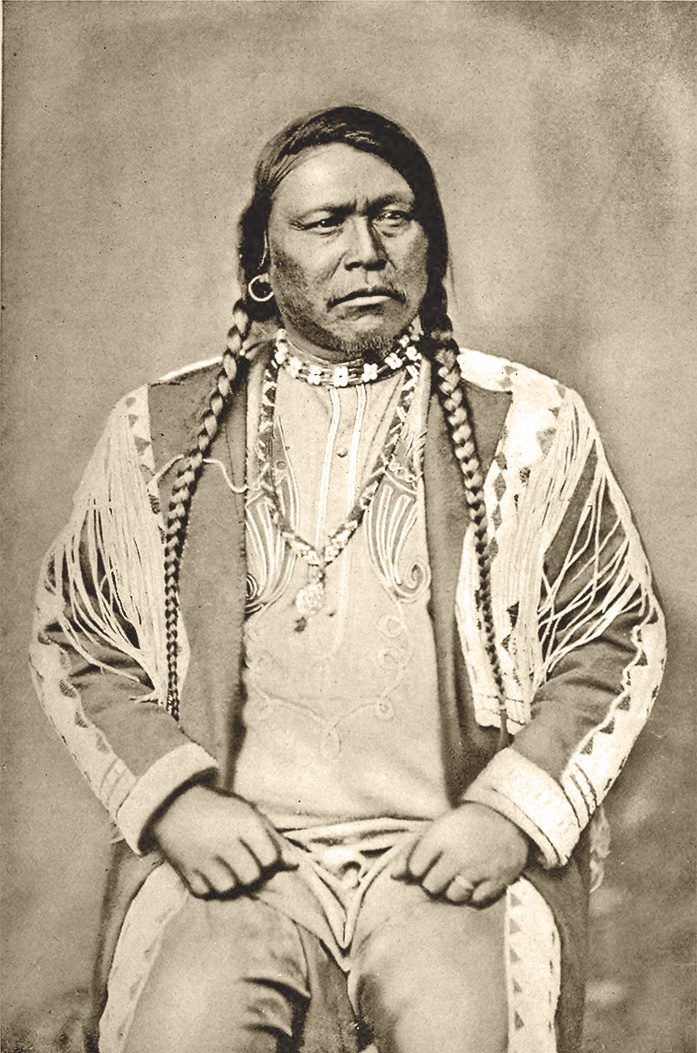

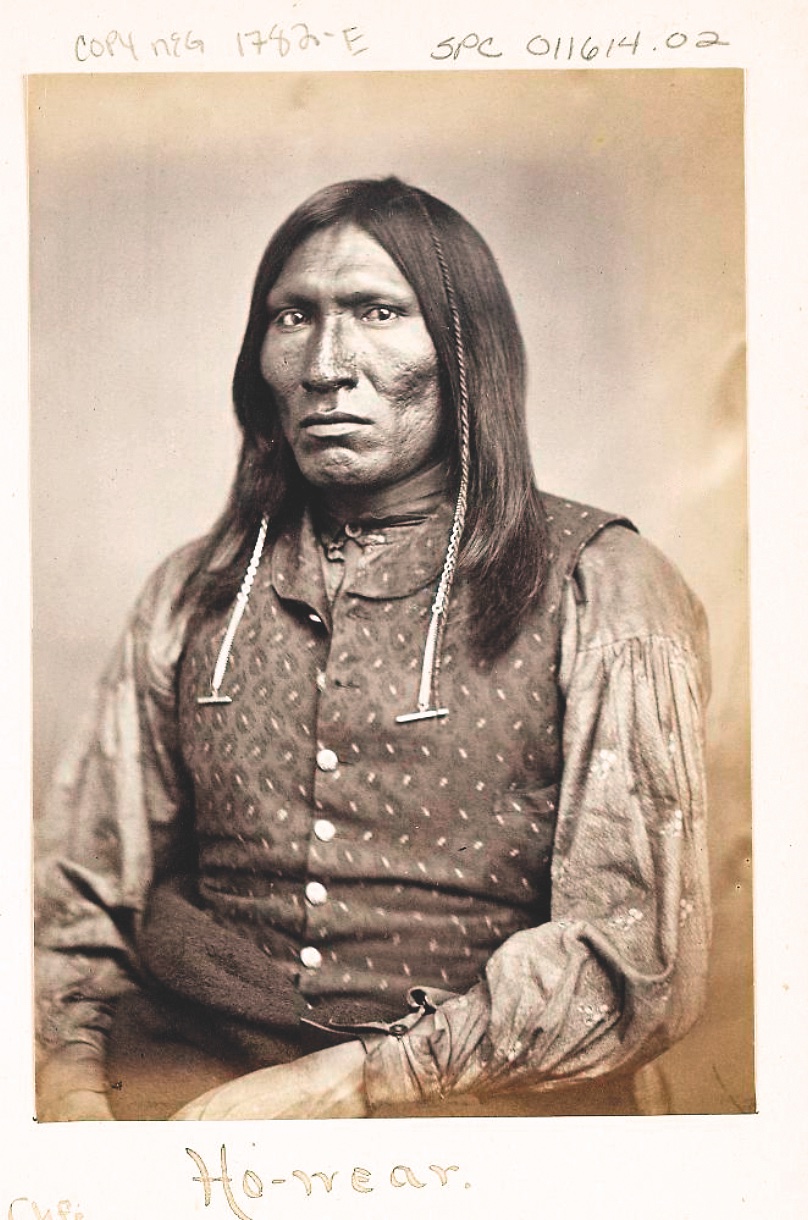

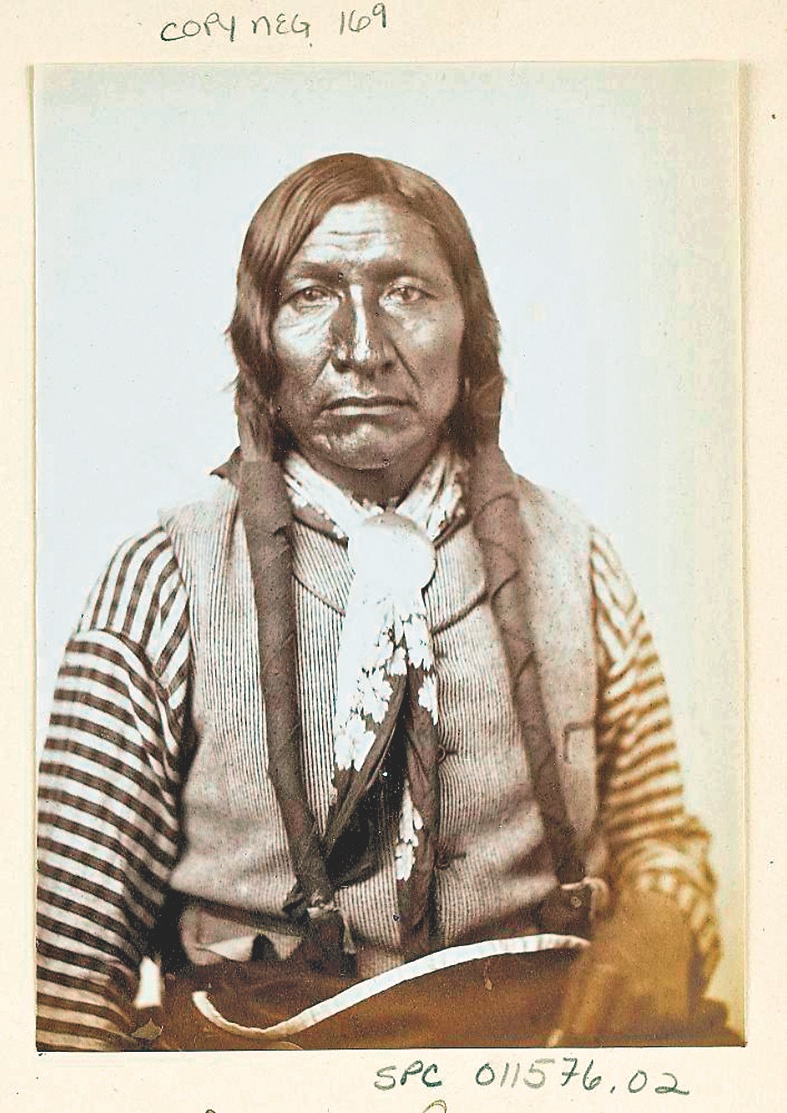

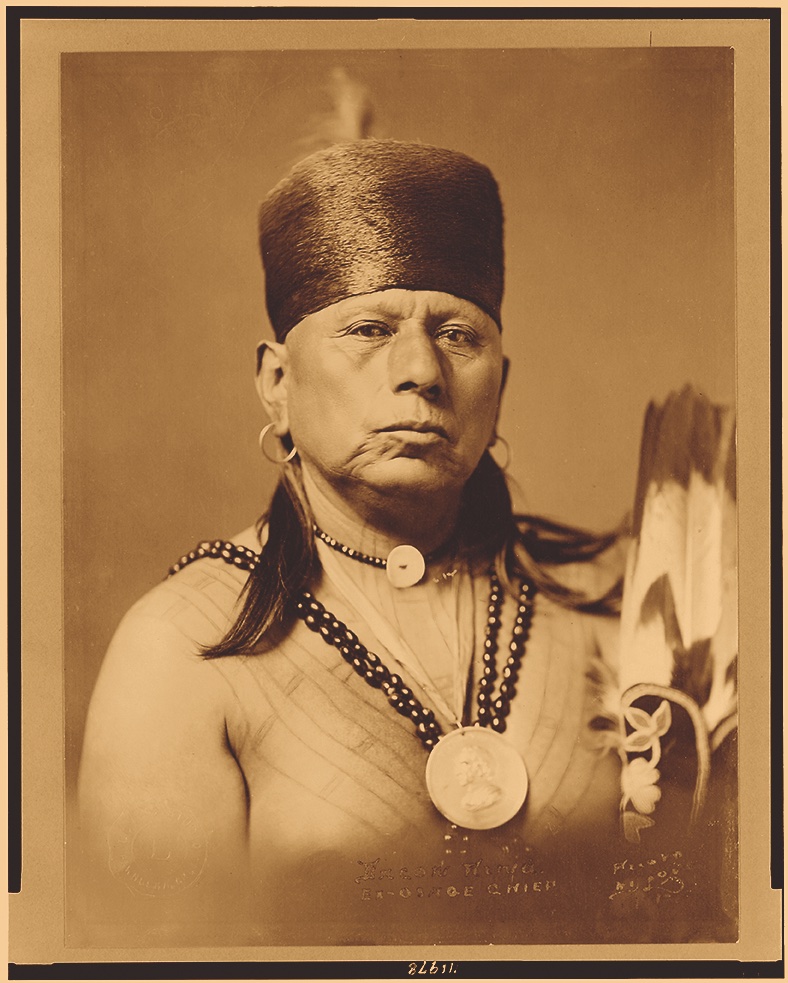

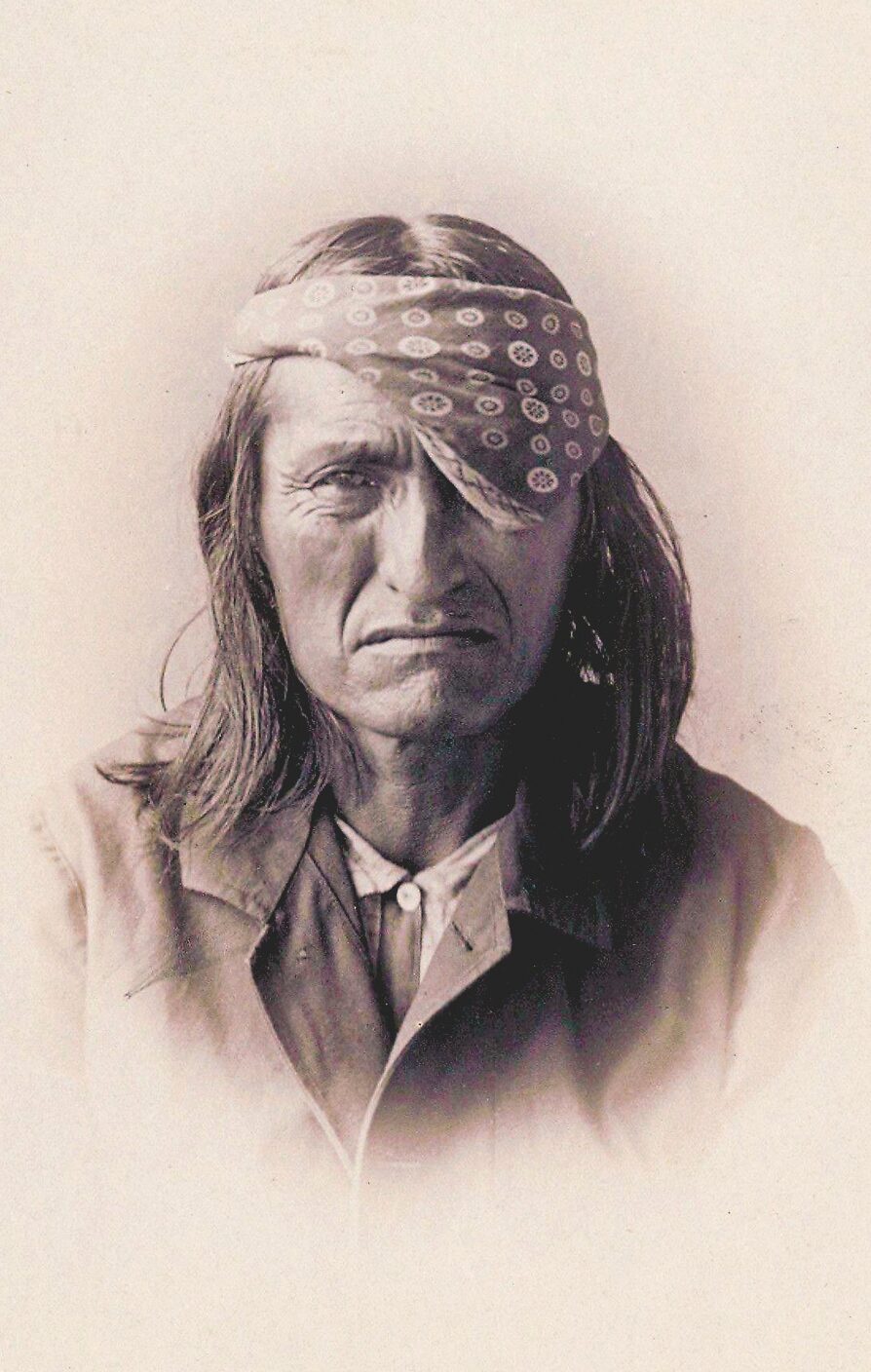

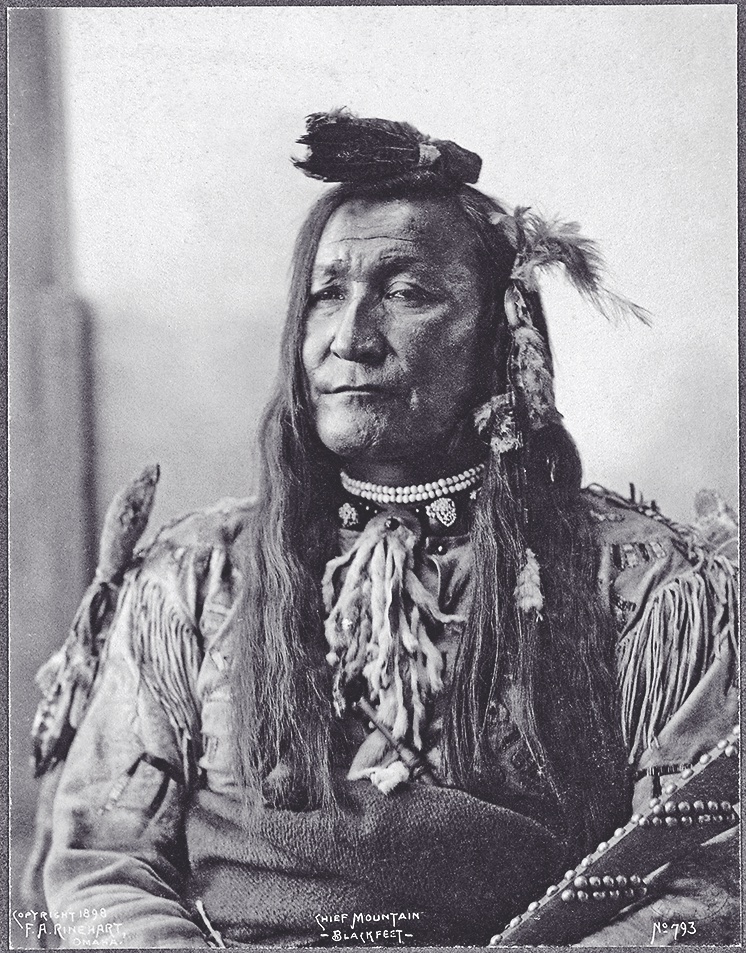

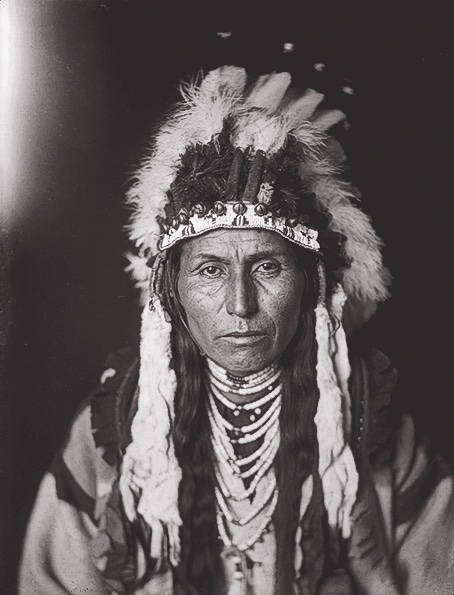

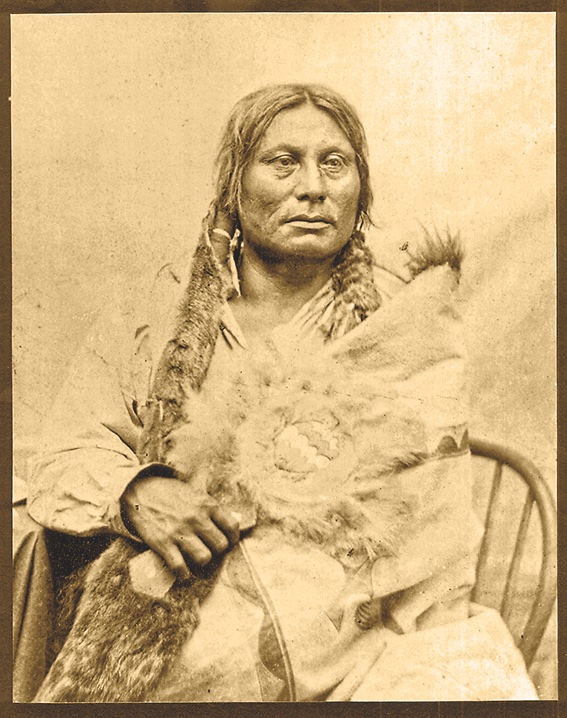

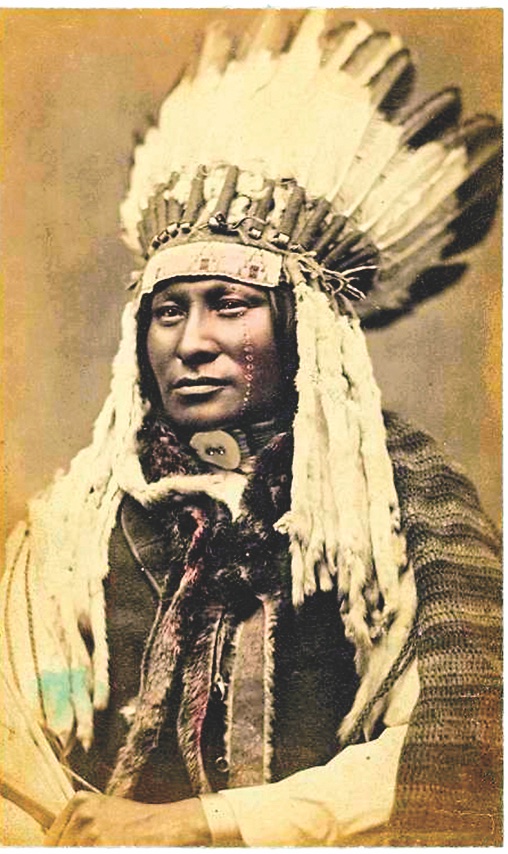

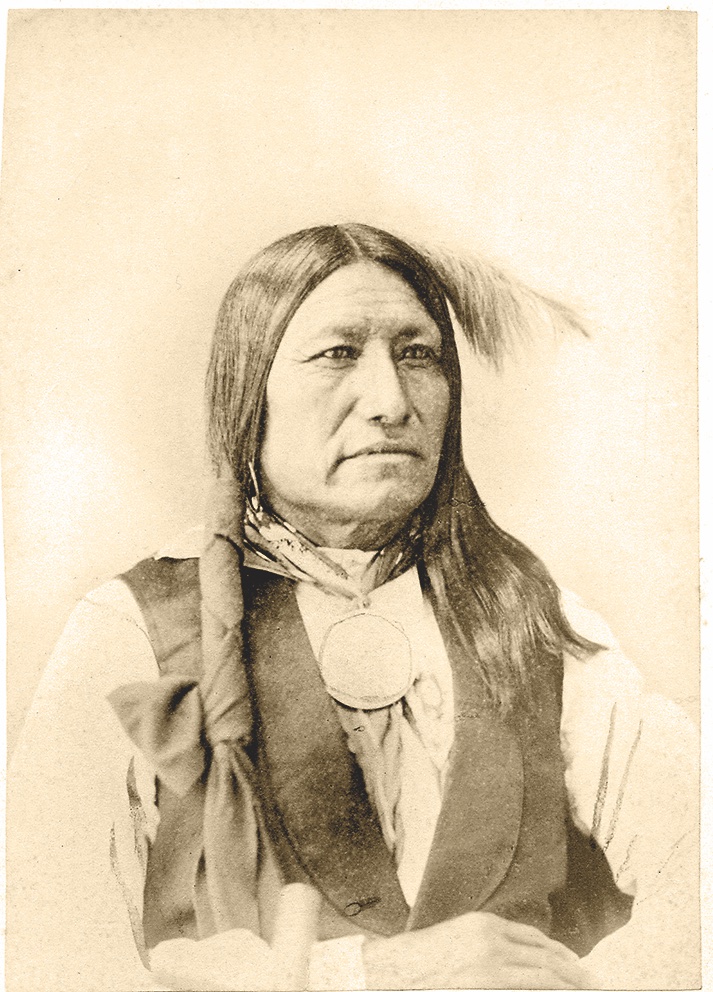

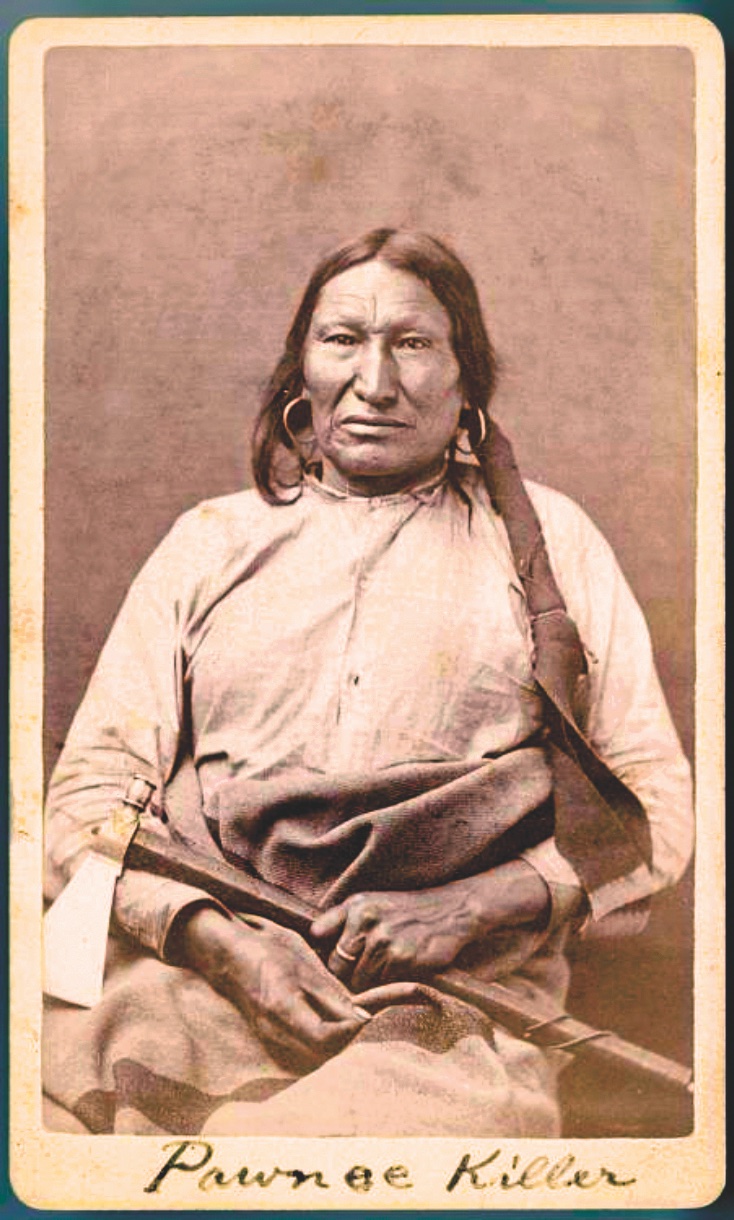

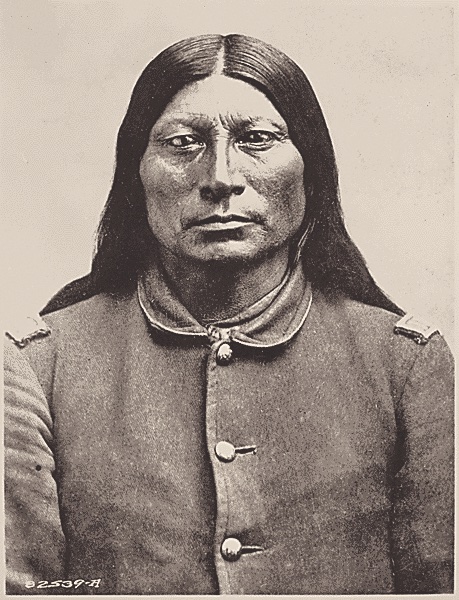

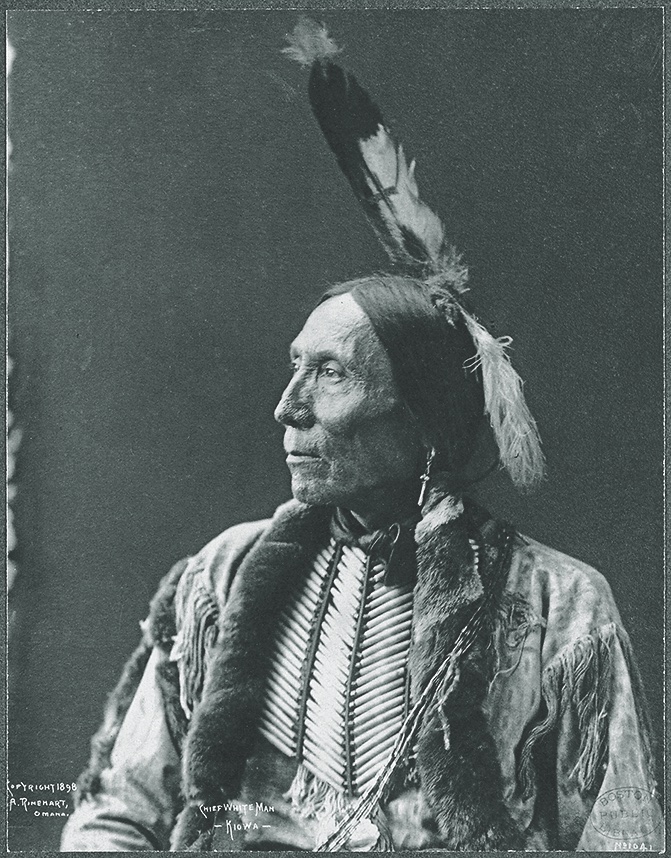

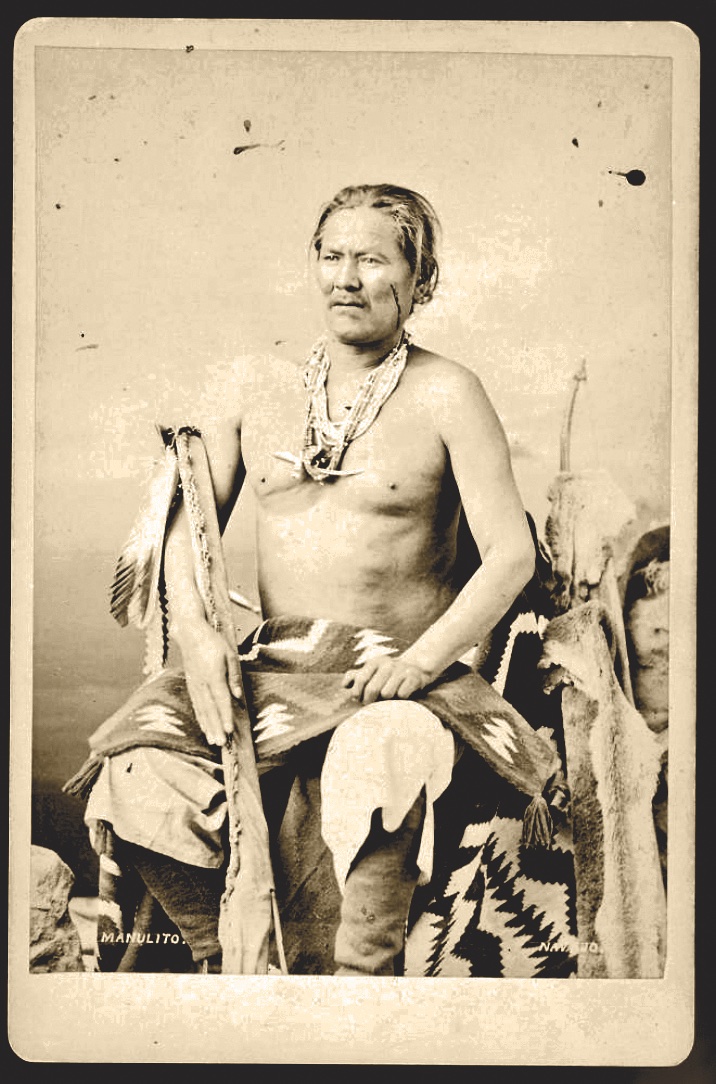

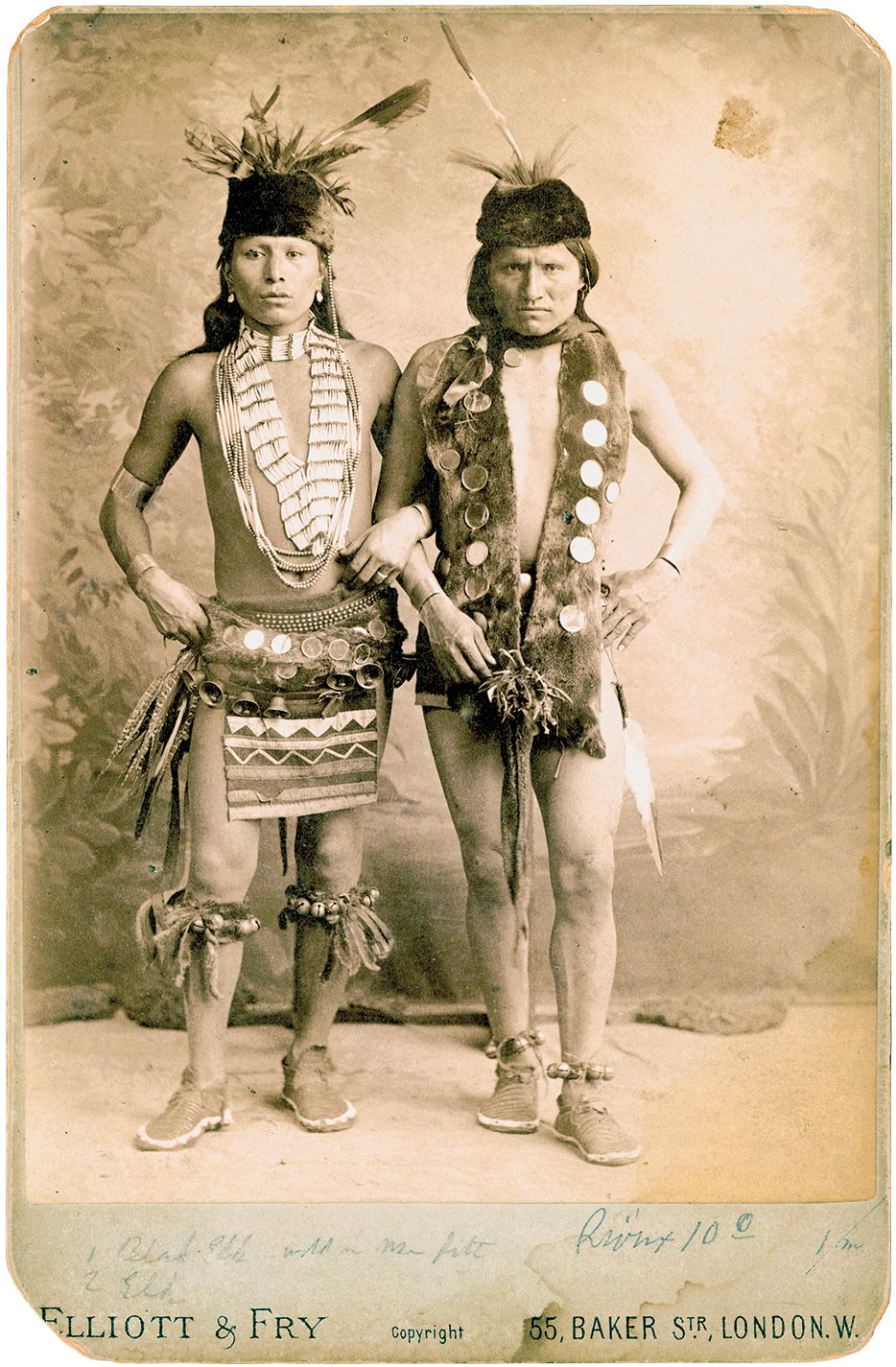

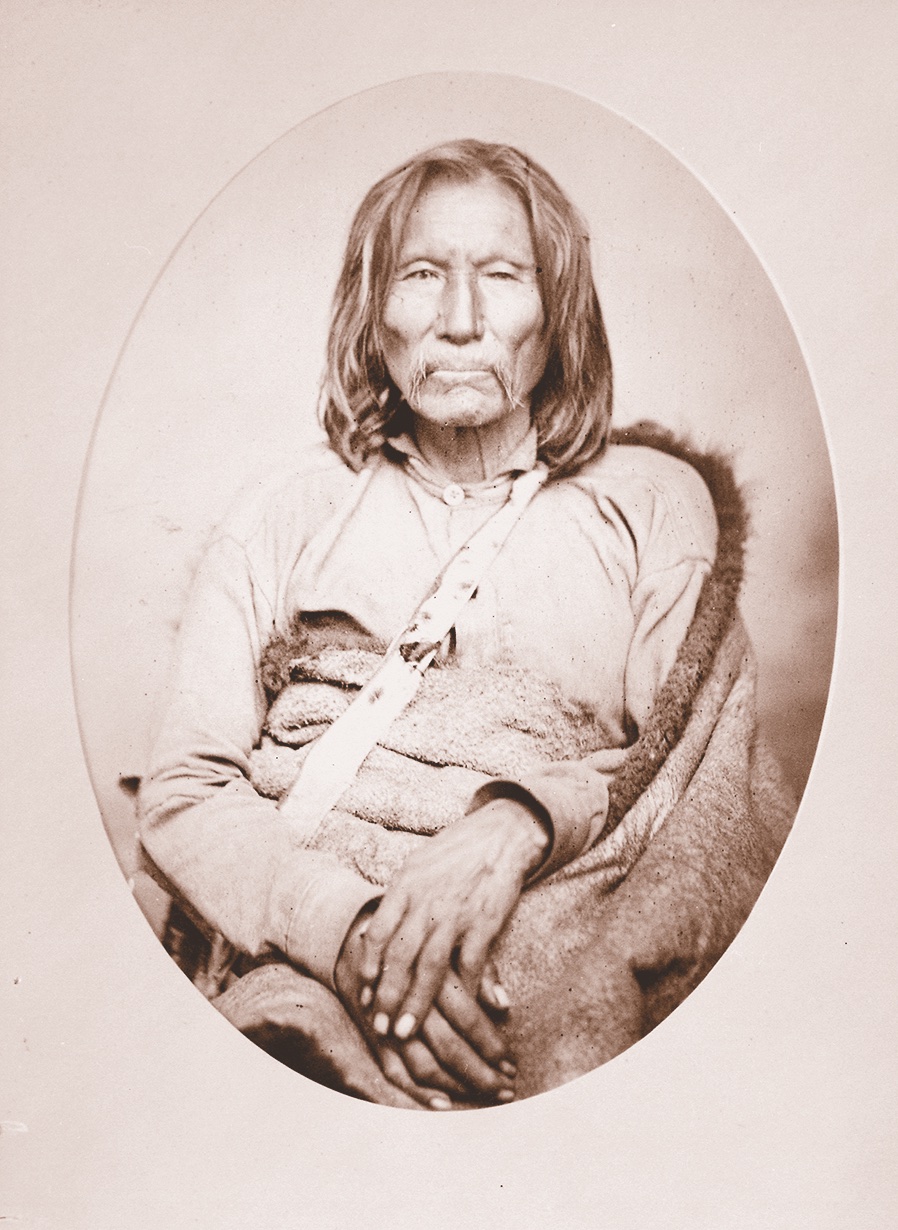

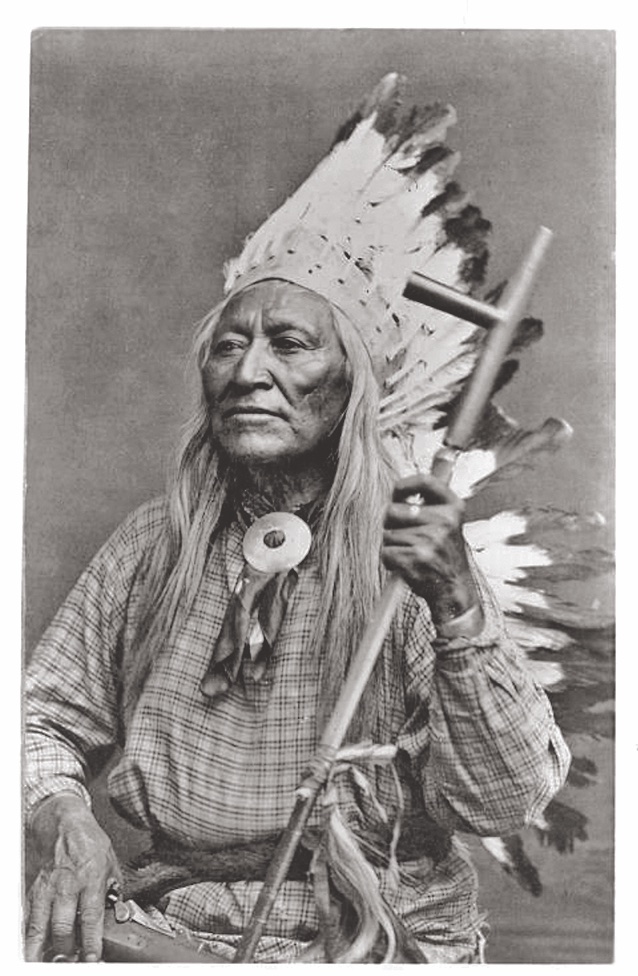

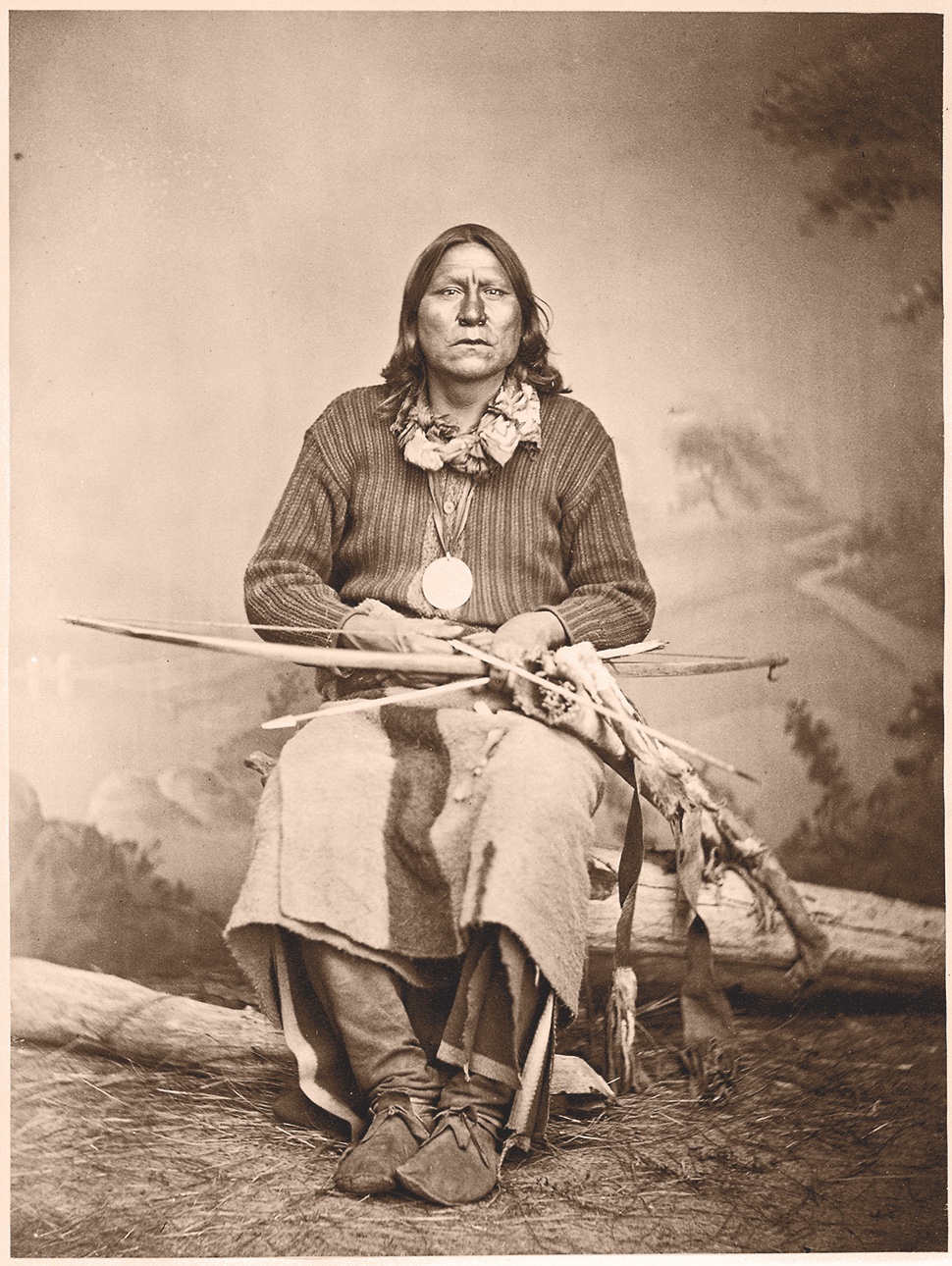

The Great Chiefs: A Photo Gallery

Courtesy Smithsonian

True West Archives

Courtesy Smithsonian

Courtesy Smithsonian

Courtesy Library of Congress

Courtesy Digital Commonwealth

Southern Cheyenne

Courtesy Smithsonian

Courtesy Smithsonian

Courtesy Smithsonian

Courtesy Yale University

Courtesy Digital Commonwealth

Courtesy Yale University

True West Archives

Hunkpapa Lakota

True West Archives

Courtesy Yale University

Courtesy Smithsonian

Northern Arapaho

Courtesy NARA, 43-0753a

Yale University

Courtesy Digital Commonwealth

True West Archives

Courtesy Smithsonian

Courtesy Smithsonian

True West Archives

Courtesy NARA, 075-BAE-1375_43-0754M

Courtesy Smithsonian

True West Archives

Courtesy Library of Congress

Courtesy Library of Congress

True West Archives

Courtesy Digital Commonwealth

Courtesy NARA, 518914