The Fearless Mirror Makers of the Arizona Territory

Arizona and the Southwest were virtually unknown in the middle of the 19th century. A few publications described travel across the area after the Mexican War and the area defined by the Gadsden Purchase as entrepreneurs flooded into California for the gold rush.

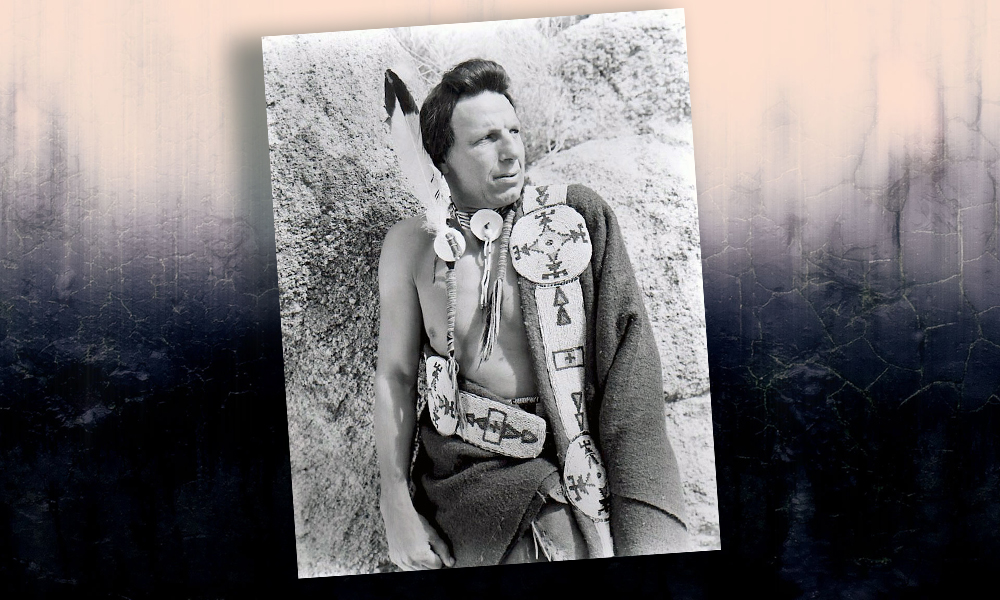

by traveling photographer Dudley P. Flanders in August 1874.

Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, Vintagephoto.com

Artist Henry Cheever Pratt’s sketches of the area appeared in the Bartlett survey report between images of the markers that were raised to demark the new border. Some showed the barren landscape and images of the survey party as they defined the new U.S. border. Others included local flora. And others featured the Native populations—Lipan Apache, Comanche, Yuma and Papago—the same tribes that would be captured a half-century later by the camera of Edward S. Curtis.

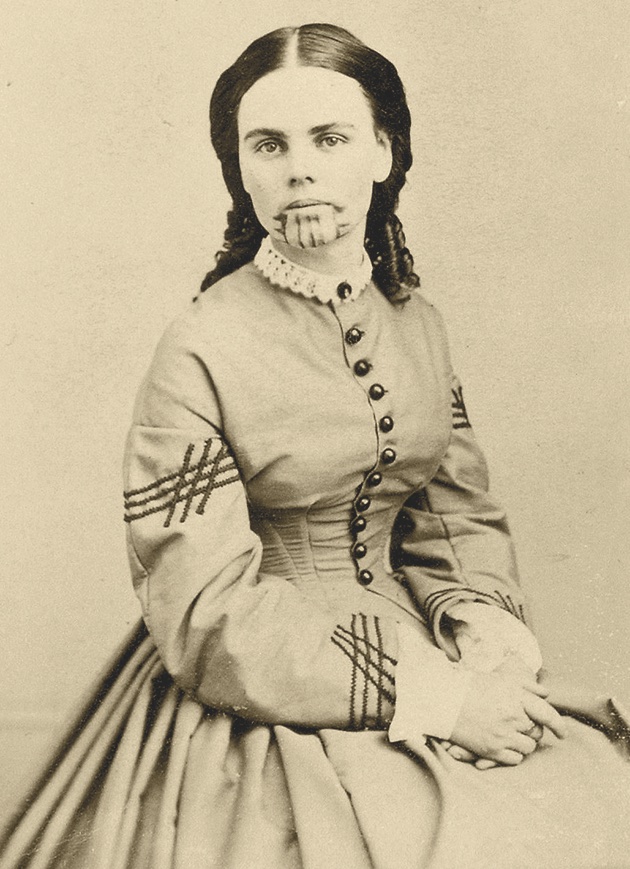

Another early source of information about the region was the tragic memoir of the Oatman family and the Apache attack on their Mormon wagon train. The story shocked the nation, and cartes de visite of their captured daughter, Olive, with her Mohave chin tattoos were reproduced in periodicals and her book.

The Colorado Exploring Expedition led by Lt. Joseph Christmas Ives traveled up the Colorado River from Yuma, and the published expedition report added images of the region and its Native population. Once again, though photography had been documenting travel images for over two decades, artists’ interpretations filtered the images that were seen in publications and shaped public awareness of the American Southwest.

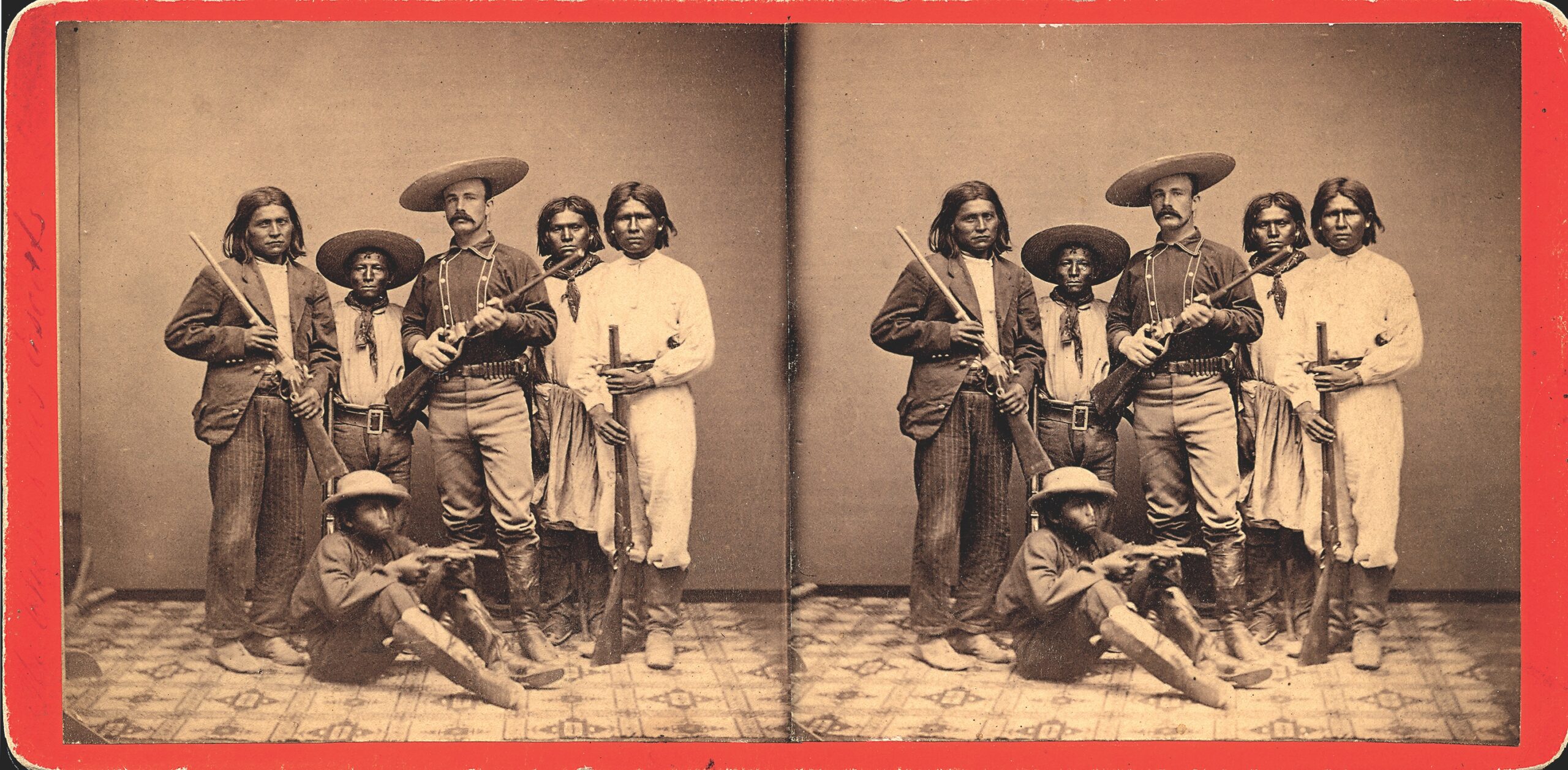

For example, though there are references to illustrations taken from photographs, the earliest photographs of Arizona identified to date are a group of stereographs by H. H. Edgerton from 1864. He made them when a group of investors and engineers traveled to Aravaipa to evaluate the possibility of reopening the mines in Arizona, as returning Civil War soldiers could help control the Native population. These images document the area and include several views of the Pima and Papago scouts and warriors who likely had been involved in the Bosque Redondo deportation.

The Wet Plate Process

These, and most images into the 1880s, were made using the wet plate process. Each negative required a piece of glass, all of the chemistry (and even water when other sources were not available), dark tent or wagon as a darkroom, camera, tripod, plate boxes and other miscellaneous supplies. An estimated 150 to 175 pounds of equipment was needed to make photographs in the field.

The glass plate sized for the camera was coated with collodion, a syrupy mixture of guncotton and ether. The plate was then sensitized in a solution of silver nitrate and placed in a light-tight film holder. After focusing and composing the images, the plateholder was inserted in the camera, dark slide removed, lens uncapped, and the plate exposed. Before the collodion dried (challenging in the dry climate of Arizona and much of the West) the plate was developed with pyrogallic acid, then desensitized or “fixed” with potassium cyanide or sodium thiosulfate, then washed and finely dried, then packed for transport. The photographer needed to safely carry the glass negative back to the studio where the images could be printed, mounted and sold.

The equipment, tents and wagons made the photographers highly visible and the potential target of thieves, bandits and raiding renegades during the Indian Wars era of the mid-1880s. We can only imagine the challenges faced by the adventurers and entrepreneurs who left the safety of their studios to travel and document life in the West during this era.

The Western Surveys

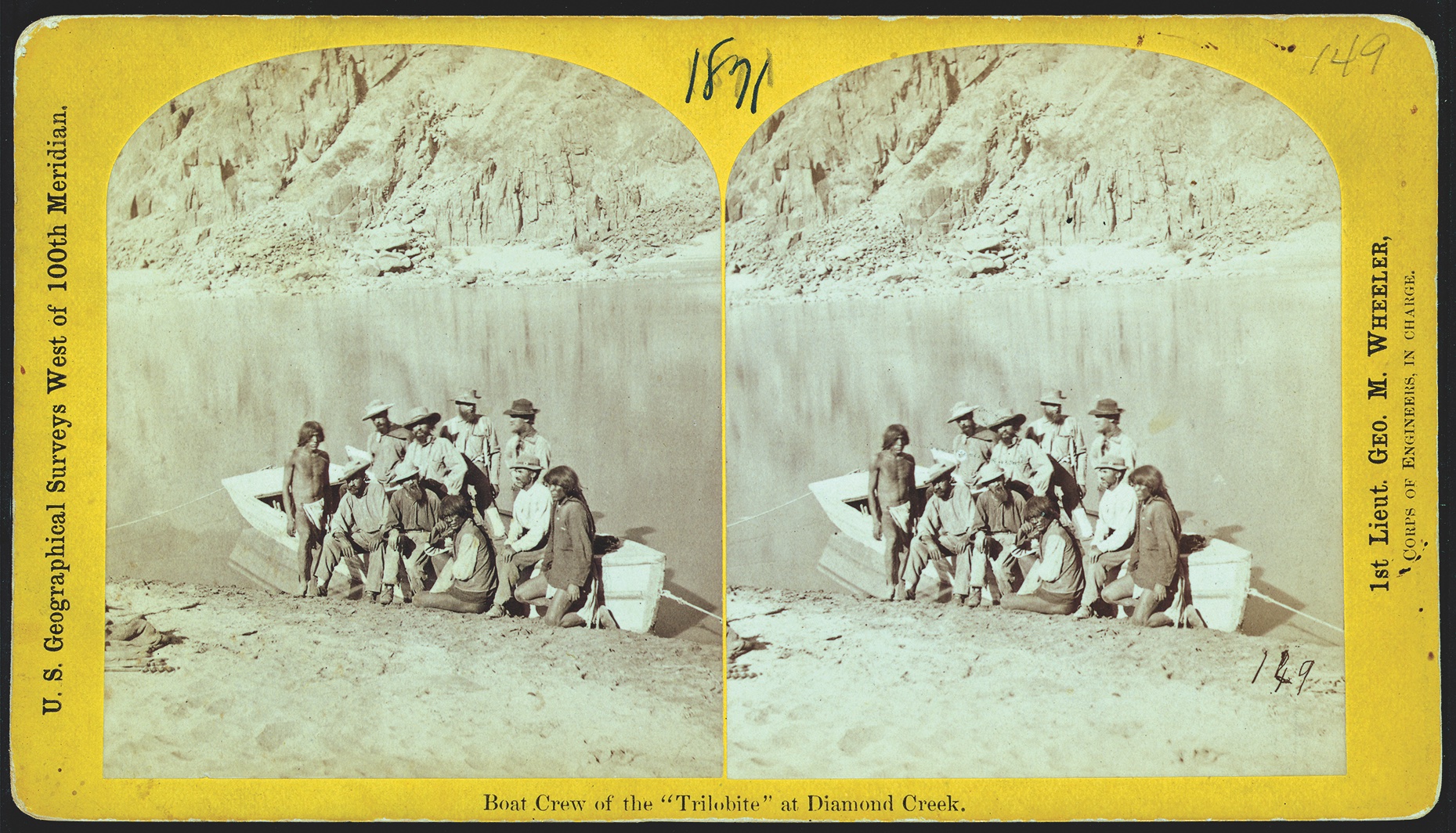

The number of images of Arizona and the Southwest that were available up to 1870 expanded dramatically with the Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian under Lieutenant Wheeler, and Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountains led by John Wesley Powell. Each survey included photographers to document the regions explored, including the Grand Canyon. Famous Civil War photographers Timothy O’Sullivan and William Bell traveled with the Wheeler party. Established Eastern landscape photographer Elias Olcott Beaman, Jr., John “Jack” Hillers and James Fennemore were primary photographers for the Powell expedition.

The Powell and Wheeler surveys captured public attention through the extensive woodcuts and illustrations derived from photographs that were reproduced in weekly periodicals like Harpers Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. In addition, both expeditions made and marketed photographs, large-format images and stereoscopic views. The images printed from the wet plate glass negatives made during the expedition were transported back East by train, then sold by photographic publishers and distributers. The images were so popular that the photos were quickly pirated and sold by many unscrupulous individual photographers and publishers.

Both Powell and Wheeler used the stereoscopic views produced during their expeditions when they traveled back to Washington to garner support from Congress for their annual funding. Powell was able to purchase a home in Washington with his share of the proceeds from selling the stereoscopic images of his expedition.

Destination Arizona

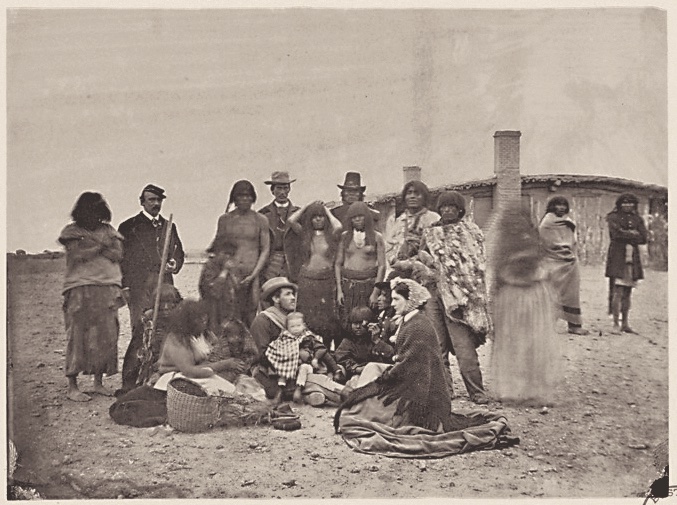

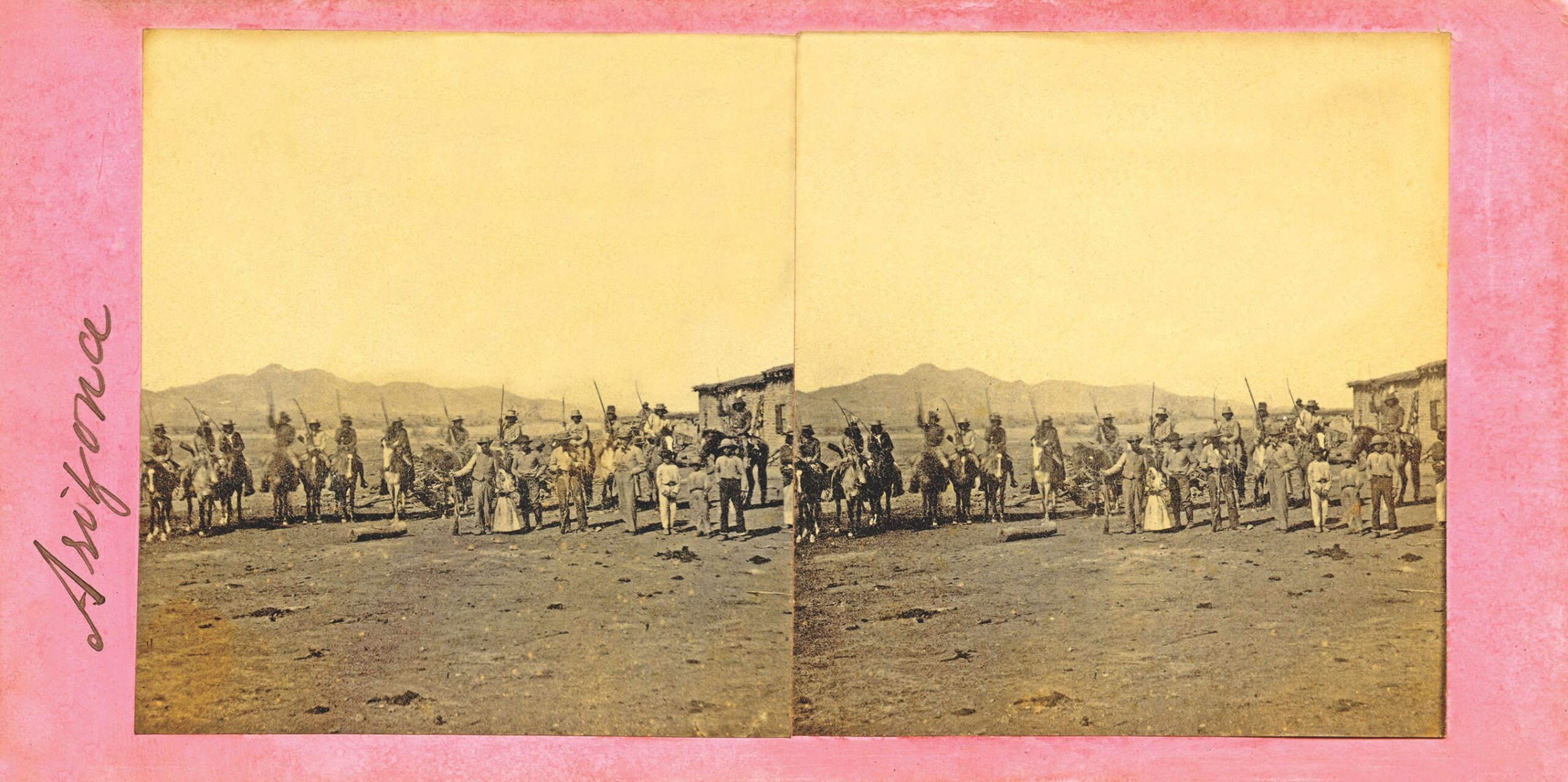

The interest in the Arizona Territory and Native population fostered by the survey images drove other photographers to visit the Arizona Territory, including Dudley P. Flanders in 1874. Flanders toured the territory visiting Prescott and Tucson, Forts Beale Springs and Bowie, and the Verde reservation as the Tonto and Yavapai tribes were gathered at the reservation, and San Carlos as they were relocated. At San Carlos in August 1874, Flanders produced a series of portraits of the Apaches and of newly arrived agent John Clum.

In the late 1870s and ‘80s the single studios that had opened in Prescott and Tucson were joined by photographers operating in Globe, Flagstaff, Phoenix and Tombstone. Some, like Camillus Sydney Fly and Henry Buehman, are familiar to aficionados of Western lore. Others, like J. C. Burge, Cicero Grimes and Charles Farciot, remain more obscure. Other famous Western photographers like Carleton Watkins and Ben Wittick were also active in the Arizona Territory—Watkins documenting the arrival of the railroad in 1880, and Wittick the life and peoples of northeastern Arizona.

These photographers added to the visual documentation of the survey images, documenting life in the growing territory, the mining and settlements, the Native population as they were moved to reservations, and portraits of key figures in the Native communities.

Arizona and its Native people continued to draw photographers, and images of the Apache, Hopi, Navajo and Yuma people were popular and salable. The stereoviews, cabinet cards and unmounted photographs could be purchased and placed in albums. After the handheld camera fueled amateur photography, the scope and volume of photographs increased dramatically.

Each photographer who went to the Southwest to make images was aware of, and likely often studied, the work of their predecessors. Technical advances in optics and emulsions made new types of images possible in terms of aesthetics, but many of the subjects were consistent over time.

The Pictorialist Aesthetic

With few exceptions, photographers of this era typically strove to make crisp, sharply focused images. Small collodion wet plate negatives, like those used to produce stereoviews, required less exposure than larger negatives and could be contact-printed to produce highly detailed prints on albumen paper. Glass inter-positives and copy negatives were produced to expedite printing larger numbers of images for resale.

Credited to the influence of painting, increasing interest in handcraft in art and photography, and later a reaction to the growth of amateur handheld cameras, a new aesthetic movement, Pictorialism, grew in the 1880s with a different aesthetic. Instead of sharply focused realistic images, Pictorialism sought to incorporate new techniques that included images with only narrow areas in focus surrounded by progressively softer areas of the image and incorporating manipulation of the image by the photographer. Pictorialism was applied to virtually all subjects, but was particularly well suited to portraits, softening blemishes and creating dramatic emotional images with sharp focus on the eyes and softer halo framing of the face and fading into the background.

Photogravure Courtesy The Tim Peterson Family Collection

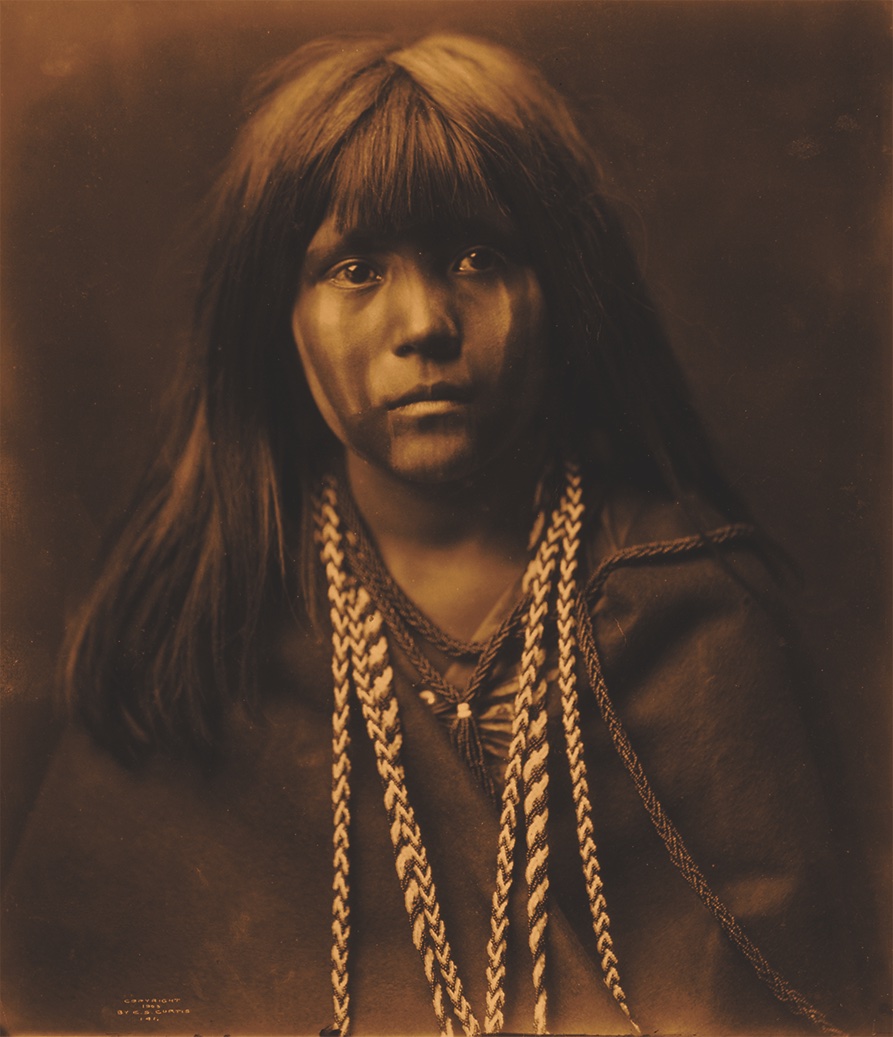

Edward S. Curtis

Edward S. Curtis began his photographic career in Seattle and produced typical commercial images of the era. Curtis followed the international trends on photographic style in publications and photographic salons and was influenced by leaders in the emerging Pictorial style, including Alfred Stieglitz. Curtis adopted a Pictorialist aesthetic for his images of Princess Angeline (also known as Kikisoblu), daughter of Sealth, chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish of Puget Sound, circa 1896. The recognition he received for these images from the National Photographic Society and his peers in 1898 likely encouraged Curtis to further explore and emphasize this new approach.

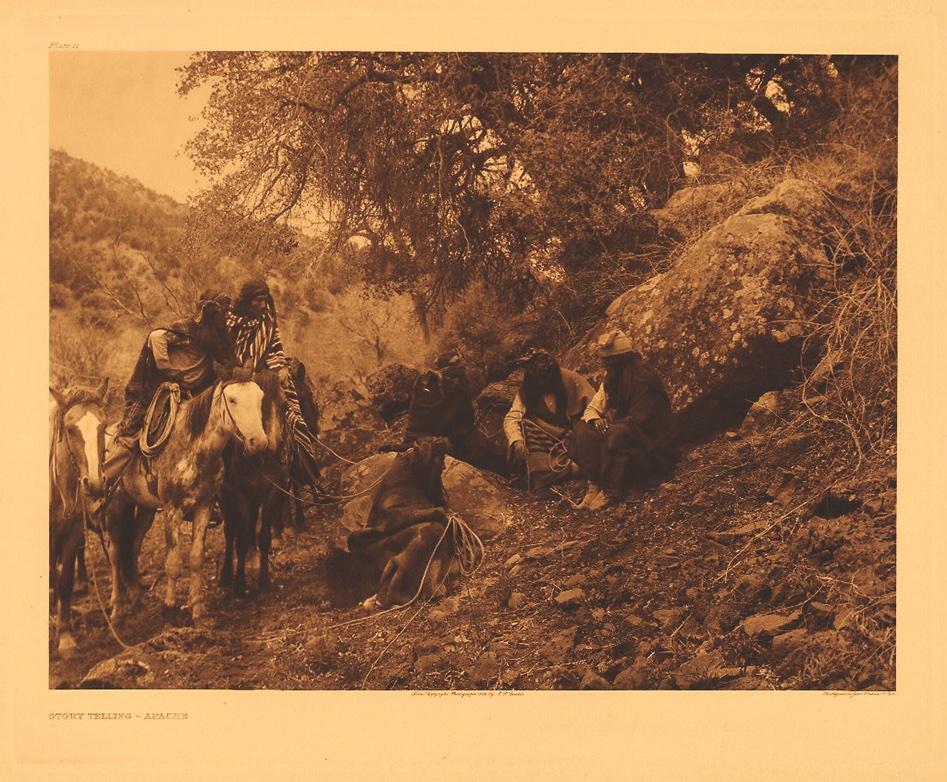

Curtis’s Pictorialist aesthetic initially focused on the Native population of Washington Territory and the Pacific Northwest and continued through much of the studio and environmental photographic portraiture produced for his The North American Indian books and folios.

In addition to the Pictorialist aesthetic, Curtis adopted other photographic media of the movement, including platinum prints, orotones and cyanotypes. Photogravures often included handwork and retouching and other creative additions to make the photographs more artistic and dramatic, and were Curtis’s favored and most frequently used format. The photogravures permitted Curtis to add Pictorialist handwork and manipulations to make his artistic ethnographic images even more romantic and dramatic.

Courtesy Library of Congress

In addition to following the trends of photographic style, as Curtis expanded his project to the tribes of the Southwest, he likely was exposed to and may have studied the work of his predecessors. Though his approach to ethnographic documentary photography was artistic and stylistic, his subjects mirrored the work of his predecessors.

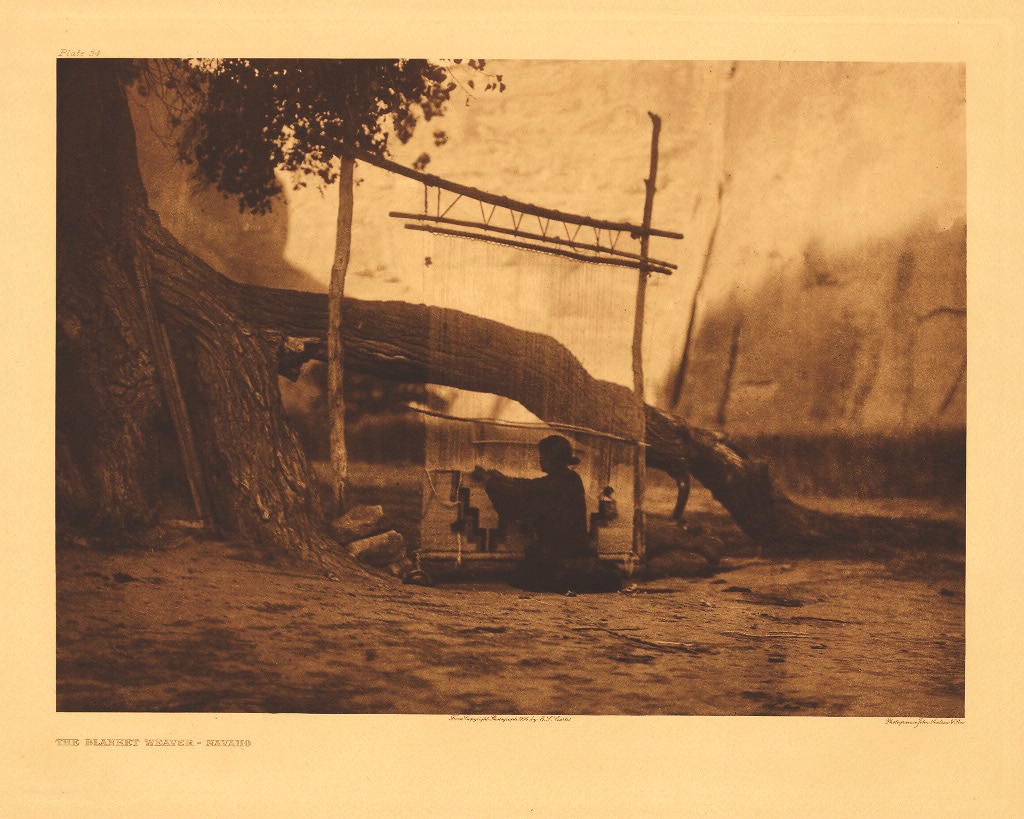

Some of Curtis’s ethnographic images, particularly his portraits, show the possible influence of the work of earlier photographers. For example, Curtis’s image of a Navajo blanket weaver shares the subject, content and approach with earlier images, including the 1873 stereoview of the Navajo weaver from the Wheeler expedition by Timothy O’Sullivan. The Native American cabinet card portraits produced by Francis A. Hartwell, both when he worked with Henry Buehman and on his own, share an intimacy and capture an interaction between subject and photographer similar to Curtis’s work. Whether Curtis also saw and was influenced by specific historic images of Arizona Native Americans is unclear, but the similarity to style raises interesting questions.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C

True West Archives

Curtis and Pictorialism

Curtis used soft-focus lenses and artistic processes that share the Pictorialist approach of Gertrude Käsebier and her portraits of the Sioux people from 1898, of which Curtls was likely aware. In Pictorialist Elements in Edward S. Curtis’s Photographic Representation of American Indians, Mick Gidley hypothesizes that Curtis was well aware of Pictorialist and American Photo-Session aesthetics. Curtis’s work shares elements of position of camera and subject, and control lighting to add shadows and create silhouettes to enhance the dramatic and romantic impact with some of Käsebier’s better-known images.

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University

Courtesy Boston Public Library

Curtis’s synthesis of the Pictorial aesthetic with the Southwestern subjects in his work, and images in Volumes 1, 2 and 11 of his The North American Indian books and folios extended the public awareness of Native peoples with dramatic, artistic portraits alluding to their past. The rich history of the 19th-century ethnographic photographs that preceded Curtis’s are lesser-known to many viewers.

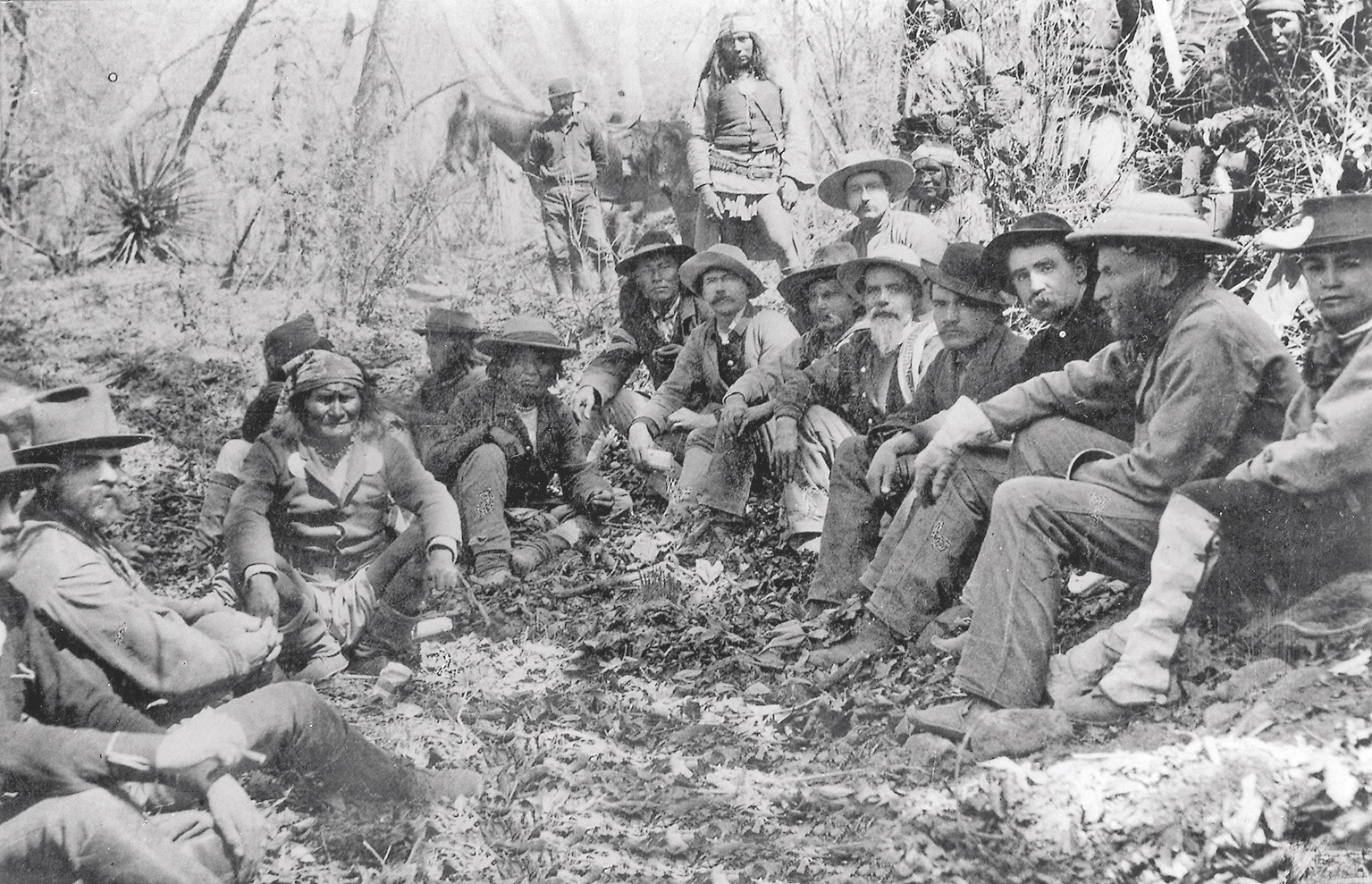

These pioneer Western photographers risked their resources and safety to capture photographs of the West in its heyday. From Flanders, who explored and documented the Arizona Territory in his wagon in 1874, to the photographers like Henry Buehman and George Rothrock, who both operated studios and traveled to make photographs, to C.S. Fly, who traveled with General Crook to Cañon de los Embudos to document the surrender of Geronimo, enterprising photographers created a legacy that we treasure today.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Curtis’s Lasting Influence

The photographers like Curtis who followed as the West became settled at the turn of the 20th century interpreted and were influenced by the images of the decades that preceded them. Whether seen in person in a stereoscope or album, or in print in the popular press, the19th-century photographs created a legacy of the “taming” of the West.

Hopefully, exploring the possible relationships between the subjects and aesthetics, and the ability to compare 19th-century images—that document the end of the era for most American Indian cultures—with Curtis’s artistic studies can help broaden the understanding and appreciation of the photographs that document this era of American history.

Jeremy Rowe is a senior research scientist at New York University and collects, researches and writes about historic 19th- and early 20th-century photographs. He is author of Arizona Stereographs 1864-1920, and serves on the Daguerreian Society and National Stereoscopic Association Boards. For more information, please visit VintagePhoto.com.

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University

Courtesy Library of Congress

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections,

Northwestern University

Courtesy Library of Congress

Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, Vintagephoto.com

Courtesy Library of Congress

Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University

Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, Vintagephoto.com

Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, Vintagephoto.com