All Images Courtesy Seattle Film Company and Milestone Film & Video

The famed photographer’s leap into silent films was anything but successful.

While Edward S. Curtis’s photographs, and especially his 20 volumes of The North American Indian, are an archive of incalculable value, their sheer vastness predetermined that they would rarely reach the common man. Curtis was on a mission: to preserve the history of a people the government was trying to—if not extinguish—homogenize out of existence. And what better way to reach the man-on-the-street than with the great entertainment form of the 20th century, the movie?

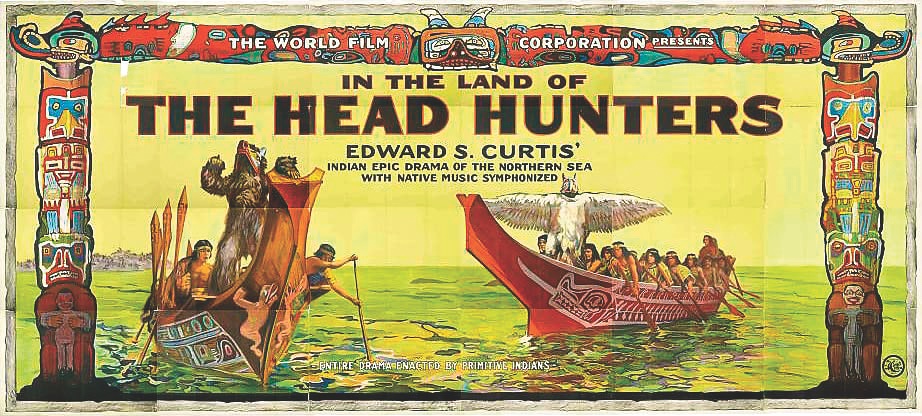

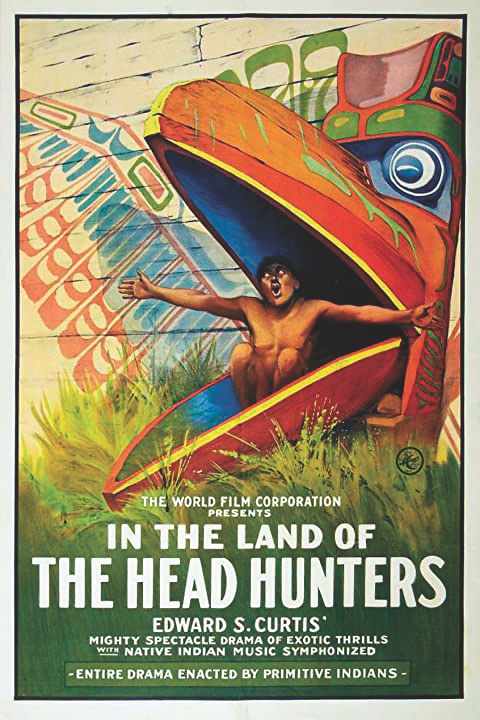

A dramatic story about Indian characters, set in the time before white men arrived in North America, would give Curtis the chance to show their way of life. Thus was born In the Land of the Head Hunters, a dozen years before the coming of sound films.

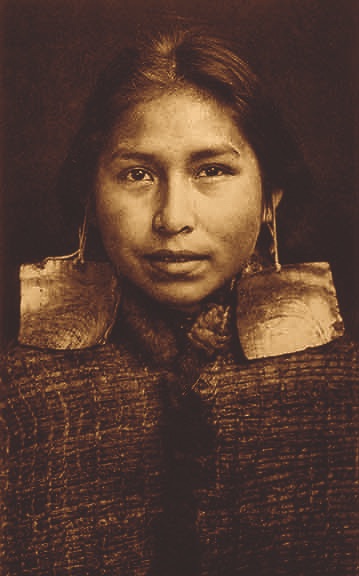

Focusing on the Kwakwaka’wakw people of Washington State and Canada, Curtis spent three years preparing and making the film. According to a 1914 issue of The Clipper, “Mr. Curtis had to live in a North Coast Village for a year before the Indians of that village and two others consented to enact for him the dramatic legends of their clans.” He gained an ally in George Hunt, who despite his Anglicized name was a Kwakwaka’wakw member. The Potlatch, a centuries-old traditional gathering of people of the Pacific Northwest—involving dancing, ceremonies, giving of gifts, wonderful masks and costumes—had been banned by Canada under The Indian Act in 1884, as wasteful and anti-Christian. Any Indian who took part was “liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than six nor less than two months.” The ban would not be repealed until 1951.

But moviemaking was not a crime; it was to be encouraged. And Curtis hired Hunt and many other tribe members to produce “movie props and costumes,” which just happened to be identical to the banned artifacts, and filmed their rituals, whose performance would have been a crime, were it not “acting.” On-set photos show that Hunt helped direct key sequences.

The story is of Motana, young son of a chief, embarking on a vision journey, fasting and performing brave deeds to increase his power. In a vision, he sees beautiful Naida, and when he meets her, learns that she has been promised in marriage to Kwagwanu, the evil sorcerer. This leads to war between their villages. Among the astonishing events filmed are Motana’s attack on an island of sea lions, the hunting of an immense—and real—whale, sea battles between war canoes, costumed dances of the grizzly bear and thunderbird, all recorded gloriously by the eye of Curtis.

The reviews were spectacular: Motion Picture Magazine said, “As a drama, it is compelling in its charm, but as a gem of the instructive film, it has rarely been equaled.” Motion Picture News noted, “Many of the scenes make one’s hair stand on end, and there are not a few who are still wondering whether these headsmen really decapitated their victims during their various battles, so realistic and true to life are they enacted.”

Motion Picture World was most impressed of all: “Mr. Curtis conceived this wonderful story in ethnology as an epic…. This production sets a new mark in artistic handling of films in which educational values mingle with dramatic interest.”

Head Hunters was a disheartening financial flop. Why? Andrew Erish, film historian and author of Vitagraph—America’s First Great Motion Picture Studio, says, “Curtis obviously hadn’t gotten to the movies very much.” The same year that Western blockbusters like The Spoilers, The Virginian and DeMille’s The Squaw Man were released, “Curtis’s love triangle is entirely dependent on [reading] the inter-titles. It’s almost impossible to identify anyone from shot to shot—there are no close-ups, no two-shots. There’s no attempt at conveying romance. There’s an utter lack of dynamics regarding individual characters or relationships.”

Even in a spectacular moment, when Motana emerges from the mouth of the whale, instead of staying in character, he mugs shamelessly at the camera, like it was a home movie. As a contemporary, and very enthusiastic, review in Motography said, “While no…acting, in the theatrical sense of the word, is attempted by the Indians, every movement breathes the primitive life in which their people were raised.” But acting is what audiences expected.

Despite a few high-profile bookings, Erish explains, “None of the big-time distributors picked it up. It ended up getting distributed by organizations that solely handled films for schools and churches.” The general public never got a chance to see the film, although it was still being booked at churches and schools into the 1940s.

Curtis made two more films, both documentaries, in 1916: The Alaskan Indians and Seeing America, about the wildlife in Yellowstone Park.

This was about the end of Curtis’s Hollywood sojourn. Although in 1923, he was named to co-head DeMille’s Camera Department, which a Paramount press release described as “the most coveted job in motion picture photography,” that job only entailed shooting stills for Adam’s Rib and the silent version of The Ten Commandments.

BLU-RAY REVIEW

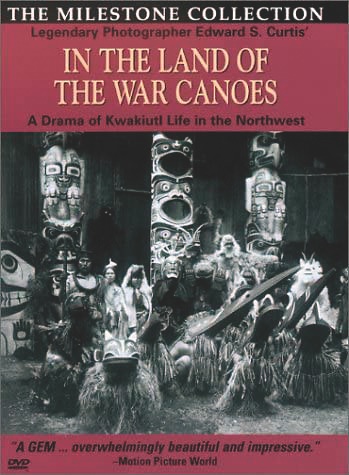

In the Land of the Head hunters (1914)

(Milestone Film & Video—Blu-Ray $39.95, DVD $29.95) More than a century after it failed to get a true theatrical release, this remarkable reconstruction of Edward Curtis’s masterpiece is now available. A 16mm print from Chicago’s Field Museum combined with recently discovered 35mm nitrate reels from UCLA and reference stills from the Library of Congress, created this version which features original color-tinting, and is accompanied by a newly recorded version of John J. Braham’s original orchestra score. The two-disc set includes new and old documentaries, featuring memories of original cast members, their children and grandchildren, and visits to locations. There are audio recordings Curtis made in 1910 of Kwakwaka’wakw chants and songs, and a 1973 reconstruction, retitled In the Land of the War Canoes (above, inset), which, though incomplete, adds convincing sound effects, dialogue and authentic Kwakwaka’wakw music.

Henry C. Parke, Western Films Editor for True West, is a screenwriter, and blogs at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com. His book of interviews, Indians and Cowboys, will be published later this year.