L.R. Millican’s life in Lampasas, Texas, was both lucky and legendary.

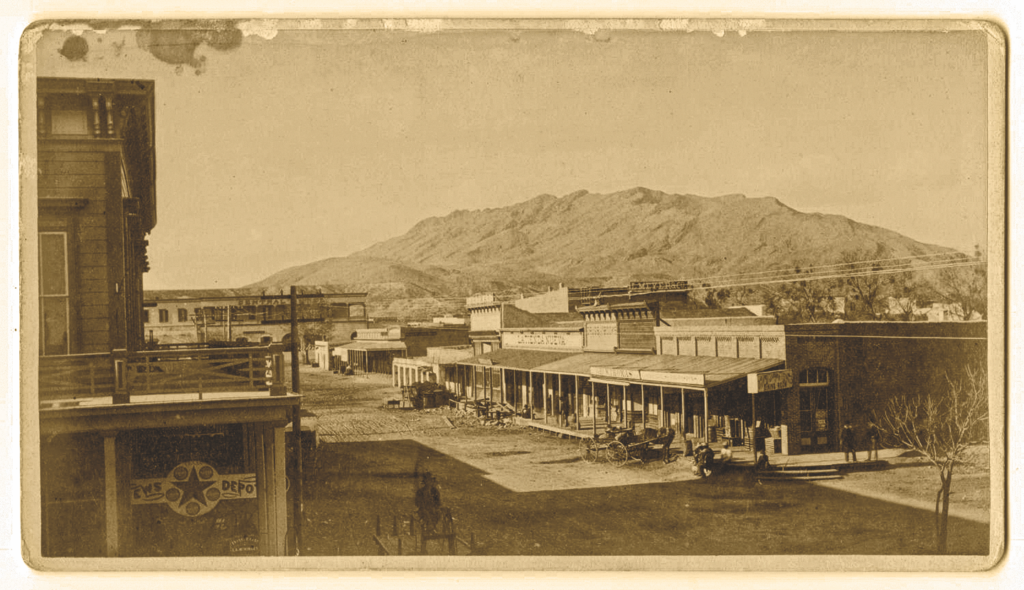

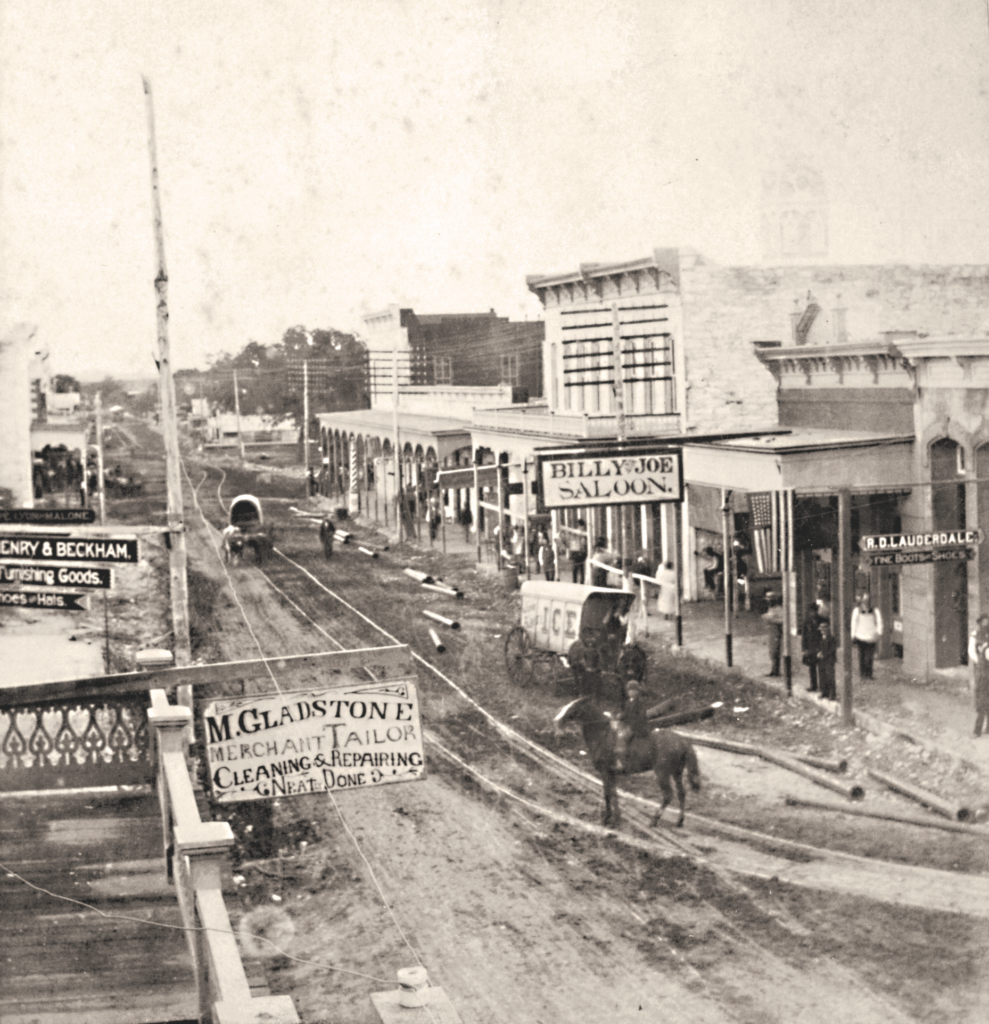

Lampasas, for a time, was on the edge of a lively frontier in Texas, and much blood spilled as that border exhaled dust and stampeded westward. Rowdy cowboys, outlaws and others shooting up saloons was commonplace on the frontier. Lawlessness, always ready to engage, leveled its Winchesters and six-shooters at the innocent, guilty and unwitting. Gun smoke lifted, and the targeted lay wounded or dead.

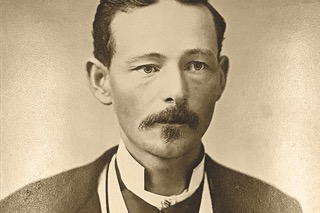

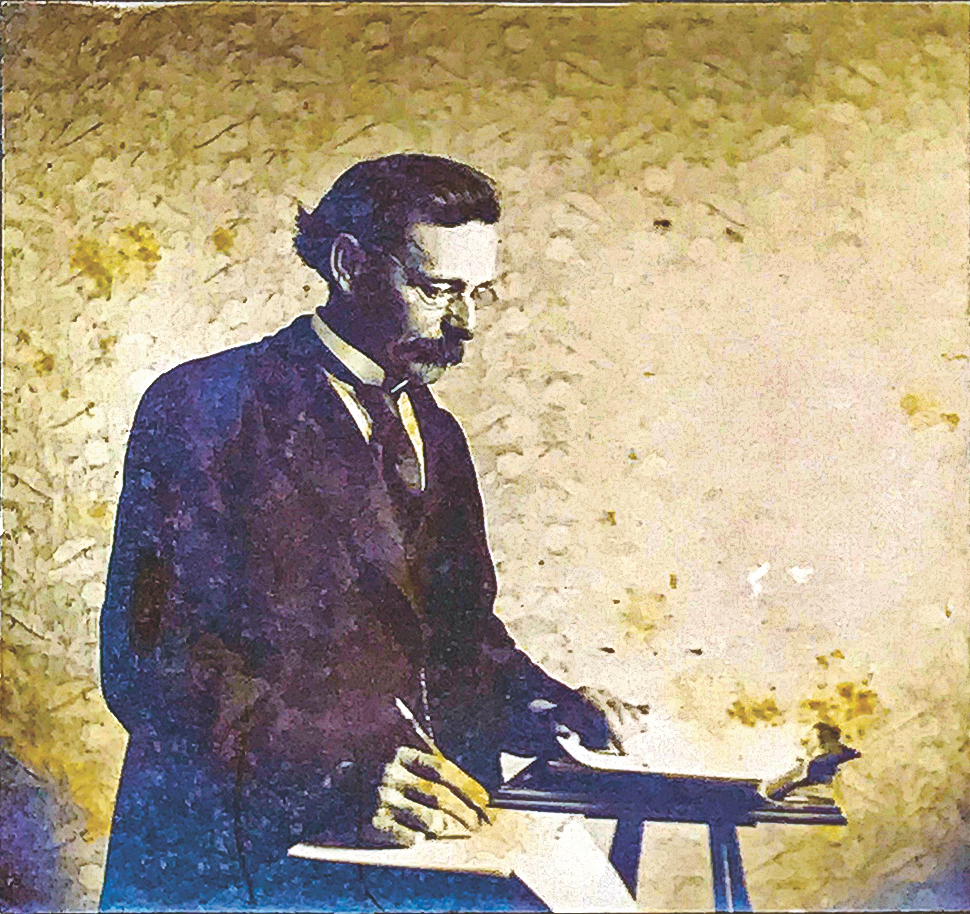

Leander Randon “L. R.” Millican lived in Lampasas as a teenager and young adult, having been born in Millican, Texas, August 27, 1853. When he became the youngest deputy sheriff in Lampasas in September 1872, he had already earned a reputation for being even-tempered, responsible and fearless. “He had a strange power over bad men. They seemed to wince and cower under the steady gaze of his unflinching gray eyes. He was afraid of no man in the flesh,” family friend Buren Sparks once observed.

Life’s circumstances shaped Millican. During the catastrophic Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1867 in East Texas, Millican’s family had fled Millican, a town established by their ancestors, and headed to Lampasas to escape death. J. W. Weaver, Millican’s stepfather, who died en route, was buried along the way. Millican’s mother, Marcella, succumbed on December 16 after reaching Lampasas, where her sister Amanda Nichols lived. Nichols and her husband, Lorenzo D., then helped raise L.R., age 14, and his younger brothers, Marcellus and Wilbur.

Millican sought employment as a teenager. He delivered mail as an outpost express rider, warily watching for Comanches on the route between Lampasas and Austin, and then worked as a young cowboy on John Sparks’s ranch in Lampasas County.

While Millican earned a living, William Lewis “Lou” Shroyer of Lampasas County did the same. In 1870 Shroyer was a local 26-year-old stockraiser, the U.S. Federal Census indicated. His wife was named Mary. By October 1873, the young family had two sons, and by 1876, Shroyer was a wanted outlaw. Millican and Shroyer crossed paths in Lampasas.

A Christmas to Remember

When December 1871 galloped into Lampasas County, the residents celebrated the holiday season. Celebratory events brought much more than the usual “good tidings of great joy.” This became the Christmas to remember. “The festivities began Christmas Eve with whisky drinking and firing of six-shooters and Winchesters on the streets, and the popping of firecrackers by the kids. All night long and the next two days and nights was this racket kept up,” the Lampasas Leader reported in a retrospective on December 30, 1898. Weaver Saloon, the “center of attraction” became “riddled with bullets” during the hijinks, but surprisingly nobody was harmed, the Leader said. Tillman “Till” Weaver, the owner of the saloon, was Millican’s step-uncle.

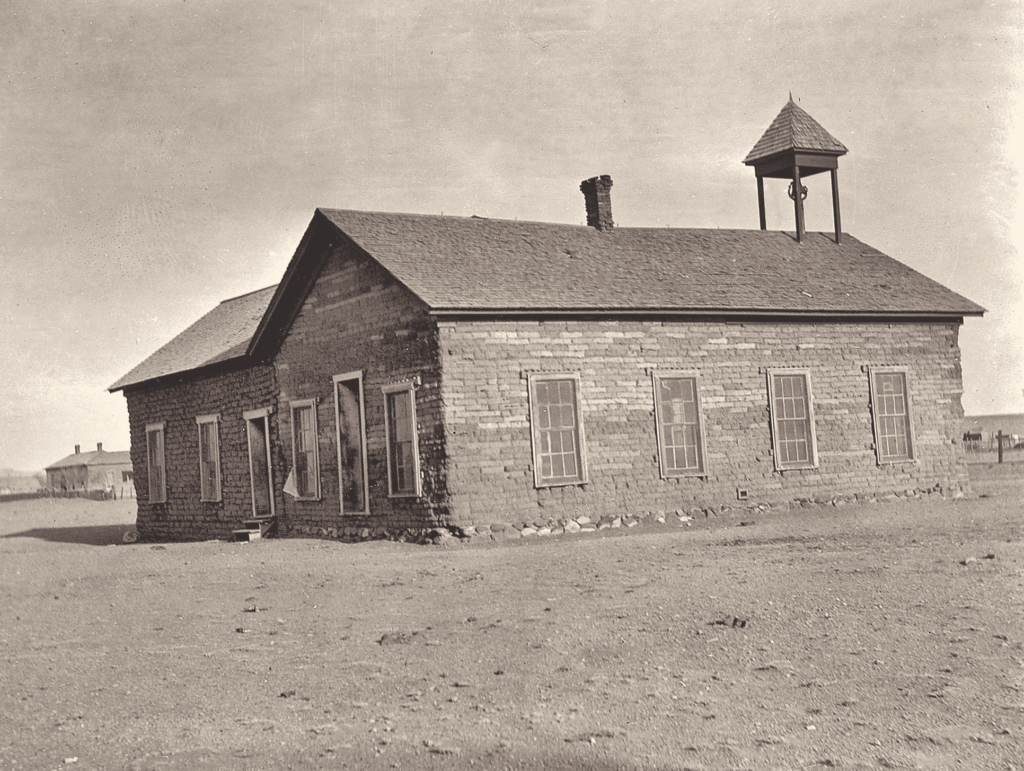

Millican prevented misdeeds from escalating during the 1871 Christmas Eve program held upstairs in a two-story two-room rock structure. Millican escorted his cousin Albina Nichols and Vic Bradford, a Nichols boarder, to the yuletide event. Festivities included music, conversation, flickering candles and neatly wrapped gifts.

Drunken Ben Horrell, probably a likable young man but possibly amused by the absurdities that freely imbibed alcohol rendered within his brain, was primed for target practice, whether indoors or outside. The Christmas chairman began distributing gifts, and Horrell, wanting to shoot out candle flames, bellowed, “Throw the candles out the window!” The Horrell brothers could be wild and were fighters. Originally held in good standing in Lampasas, events, choices and the fight for survival possibly drove some of the brothers to lawlessness in subsequent years.

Millican quickly snuffed out two candles and escorted Nichols and Bradford to the stairway, quietly urging them and others to leave. Horrell loudly bawled more directives. Millican, using a ploy involving the recognition of good manners, asked Horrell for assistance to keep the young men back so that older men, women and children could exit down the narrow stairs first. Seemingly eager to help, Horrell bounded over wooden benches, knocking them aside.

After the building had emptied, Horrell demanded target practice. Millican and Horrell now stood outside. Millican threw a candle into the air, and Horrell expertly killed it, its brief life extinguished. The immediate danger dissipated after Horrell shot another candle.

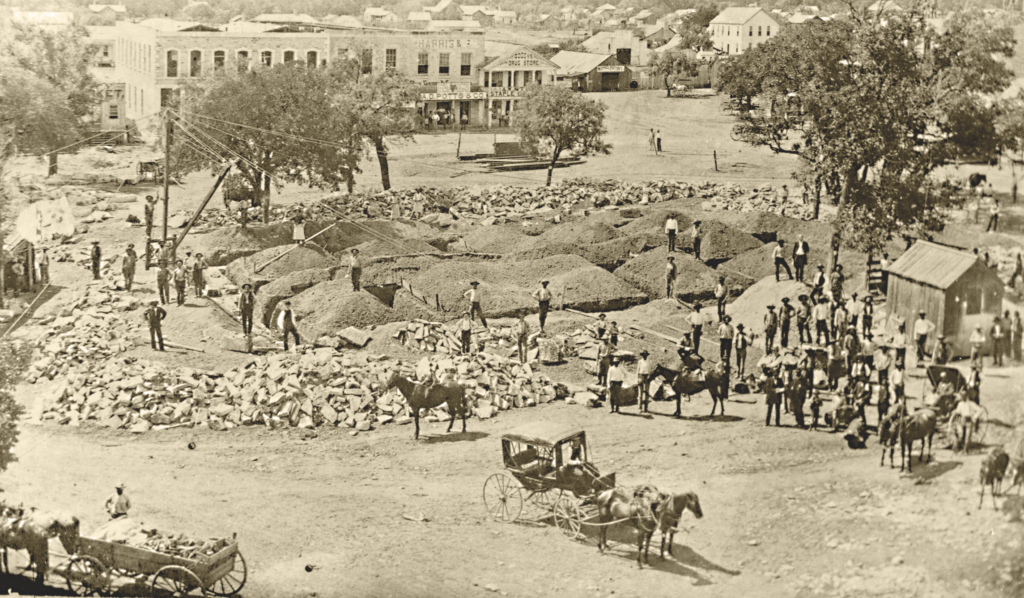

The 1871 holiday events continued merrily. Shroyer, highly spirited on Christmas Day, waved a six-shooter and rode his horse into a saloon. The revelers drenched the horse in alcohol, the Leader said. More misdeeds occurred. A man named John West rode his horse into Dr. W. A. Frazier’s drugstore. On Christmas night the building serving as the courthouse inexplicably burned down on the north side of the business square. The county’s early legal records went up in smoke.

A Youthful Lawman

The ensuing months brought changes. On September 9, 1872, 19-year-old Millican received his formal emancipation papers in Lampasas from Judge E. B. Turner, who had removed the youth’s status as a minor. Justice of the Peace Thomas Pratt soon commissioned Millican as a deputy sheriff.

Sometime prior to Millican’s commission, Shroyer was in town for a friend’s trial. A crowd gathered, expecting trouble. Reports of the event and words exchanged during the confrontation surfaced later.

Sheriff Shadrick (Shadrack) T. Denson asked if anyone would accompany him to disarm Shroyer. No one volunteered, but finally a tall young man said, “I’ll go.” Millican stepped forward without a gun but would use something more effective—carefully selected words, calm demeanor and a level gray gaze.

Denson approached Shroyer and asked for his gun, explaining that trouble was developing, and no one except a law official was to wear a gun in town.

“Well, I don’t know whether I will give up my gun or not,” Shroyer said.

Millican then pointed to the gathered men and quietly explained to Shroyer that they were ready for trouble if it arose, although nobody wanted it. “Now you can, if you will, do more to help us than anybody in town. All you have to do is lay aside your guns, get your crowd together, keep it away from whisky, to keep things peaceable. Otherwise, nobody can reckon the consequences,” Millican said.

Shroyer eyed Millican and Denson.

“All right, boys. I’ll keep my boys from making a fuss,” Shroyer finally conceded. “We will stroll over, and I will leave my guns with old Uncle Till.” He kept his word, handing his guns to Weaver in the saloon.

As a nod to the pervading lawlessness and ruthlessness on the Texas frontier, consider Shroyer’s premature death. Wild Bill Longley, Texas outlaw, befriended, shot and killed Shroyer in Dry Frio Canyon, Uvalde County, January 10, 1876. Why? A bounty had existed on Shroyer.

The Horrell Brothers

Millican’s life became entwined with some of the Horrell brothers: Ben, Mart, Merritt, Sam and Tom. Although they appeared to respect Millican, on one occasion one or more of them pilfered his horses. Millican, alone, a pistol in his pocket, sought the Horrells and took back his horses. Millican was part of a posse that searched for the Horrells and others following a series of March 14, 1873, shootings in Jerry Scott’s Lampasas Saloon that resulted in the deaths of four state police officers. Authorities eventually captured and arrested Mart Horrell, James Grizzell and Allen Whitcraft (Whitecraft) for their part in the officers’ deaths. Additional fugitives remained elusive. On May 2 the Horrells and a group of men broke Mart and others out of jail in Georgetown, Texas.

Some of the Horrells and their cattle started for Lincoln County, New Mexico Territory, later in 1873. Disagreements tied to a faulty land sale to the Horrells, cattle sale proceeds, water rights and racial tensions developed there. Ben’s drunken spree on December 1, 1873, in Lincoln resulted in his death, triggering the ill-fated Horrell Wars in Lincoln County. By Feb-ruary’s end 1874, the beleaguered family had returned to Lampasas.

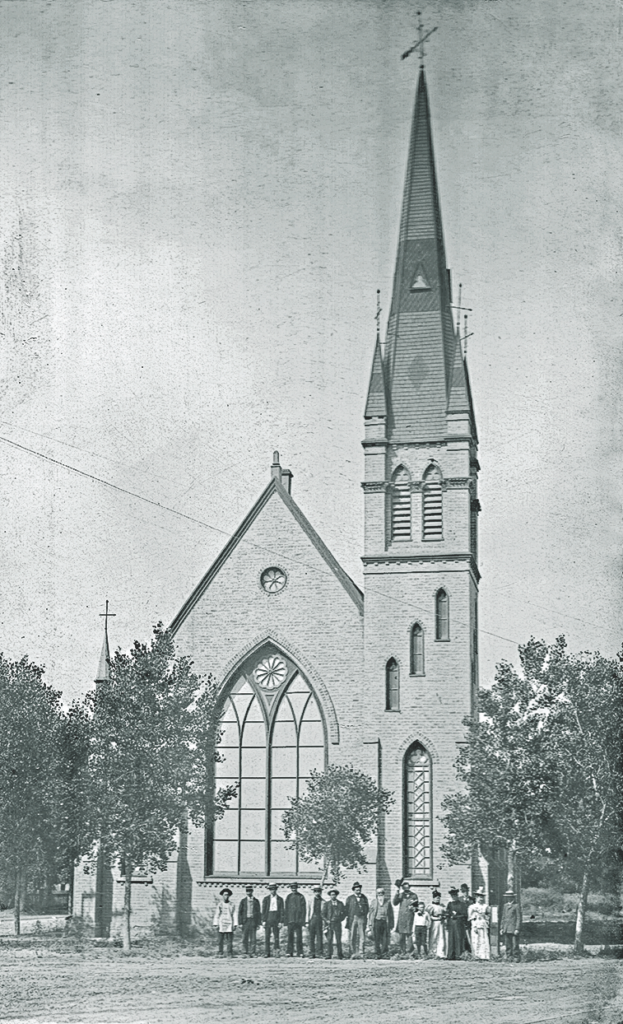

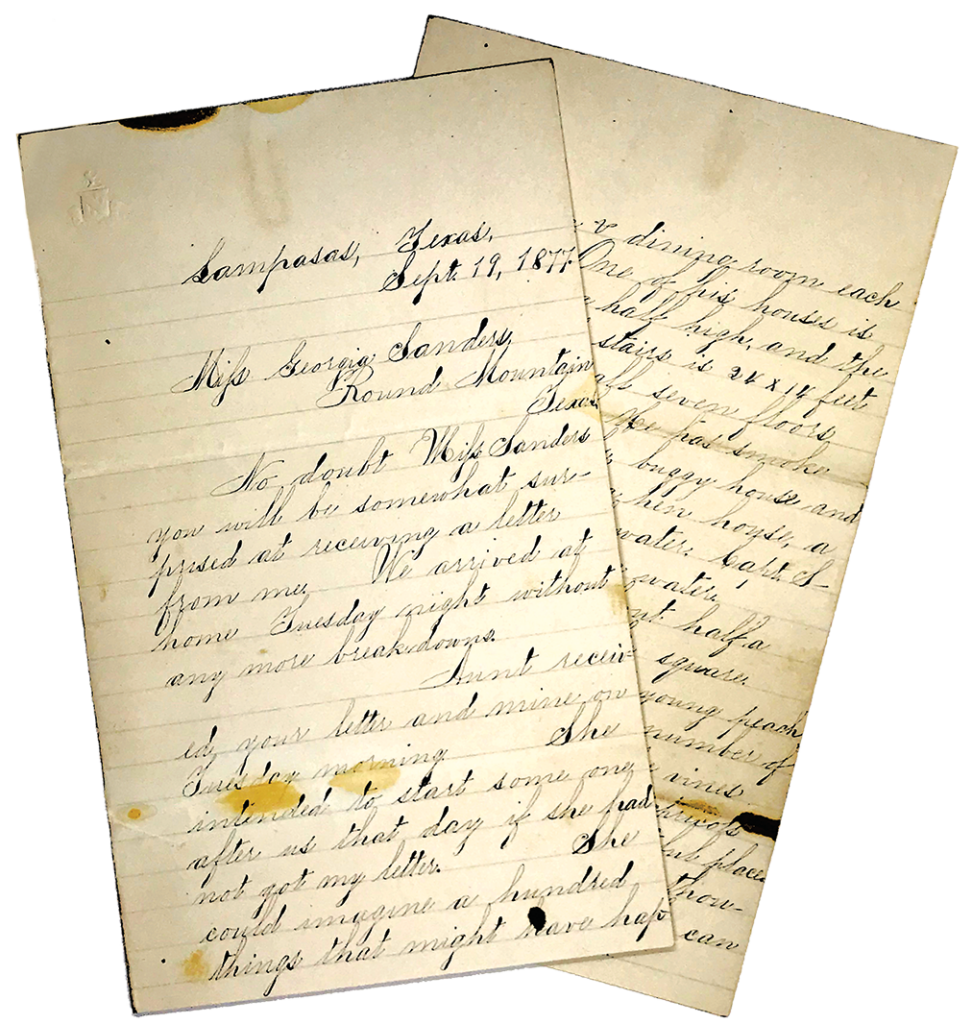

The year 1874 was pivotal for Millican. In August he was converted at an old-time Methodist Camp meeting, Cherokee Creek, San Saba County. On December 20 he adopted Baptist doctrines and was baptized the following day. He was licensed to preach the first Sunday in February 1875. The First Baptist Church of Lampasas ordained him in February 1878. Shortly thereafter, Millican married Georgia Katherine Saunders on February 12, 1878, in Blanco County.

Trouble dogged the Horrells. Cattle rustling charges arose more than once. On January 22, 1877, Pink Higgins sought Merritt Horrell in the Gem Saloon in Lampasas. “Mr. Horrell, this is to settle some cow business,” Higgins said, fatally shooting him and igniting the lethal Horrell-Higgins blood feud.

Lawman to Preacher

The Horrells turned to Millican, now a Baptist preacher. At the family’s request, he officiated the burial service for Merritt. Millican counseled the remaining brothers afterward, suggesting they embrace religion. Although expressing a desire to do so, they felt their lives had reached a turning point, and a dark road lay ahead for them.

The Horrell-Higgins feud blazed throughout 1877, climaxing in a deadly shootout June 7 in Lampasas. Major John B. Jones, commander of the Frontier Battalion of Texas Rangers, and his men were dispatched to Lampasas to provide order. Jones served as the intermediary to effect a peace treaty in late July, which the Horrells signed July 31 and the Higgins faction on August 2.

Lampasas held steady. Millican, his religious pamphlets and black frock flying, galloped his unruly horse westward in the early 1880s. With a horizon plainly visible within his serene gray gaze, Millican, the “Cowboy Preacher,” increased his Western flock. He established or financially stabilized Baptist churches in the Texas Hill Country, West Texas and New Mexico. Ironically, preaching in a Pecos, Texas, saloon in later years, Millican converted a young man named James Samuel Horrell, son of John W. and Sarah of Lampasas.

Courtesy Millican family descendants

Millican’s human life ended April 18, 1938. The Horrells were part of his history and that of Lampasas.

Kenyon Bennett researches in Texas and writes about Old West history. Her current long-term projects focus on cattle drives and a circuit-riding preacher from Lampasas County, Texas. She is the features coordinator and journalist for The Democrat Tribune and The Dodgeville Chronicle in southwestern Wisconsin.