From Montana to Texas, a summer road trip is a great way to immerse yourself in the history and heritage of the American West.

I remember my parents loading my sister, Katherine, and me into the family station wagon. It was the late 1960s and our vacation destination was almost always my grandmother’s home in Phoenix, Arizona. To avoid the heat in the summer, my folks usually left very early in the morning (like 1 a.m. early) from North Hollywood. On Interstate 10, the city gave way to the desert outside Palm Springs. My dad never missed a gas stop in Blythe before crossing the Colorado River. Before the interstate was completed, the Arizona leg of the trip was on U.S. 60, past the cotton fields and little villages of the Harquahala Valley, into the cowboy town of Wickenburg, then south into Phoenix as the sun was coming up. We always felt a great relief to be back at my grandmother’s and excited for the adventures our parents had planned for us.

Over 50 years later, I still love the excitement of a road trip with my wife and family. The thrill of planning the vacation, mapping the route, researching the places we will see—it never grows old. The anticipation is priceless. We just don’t leave at 1 a.m. in the morning.

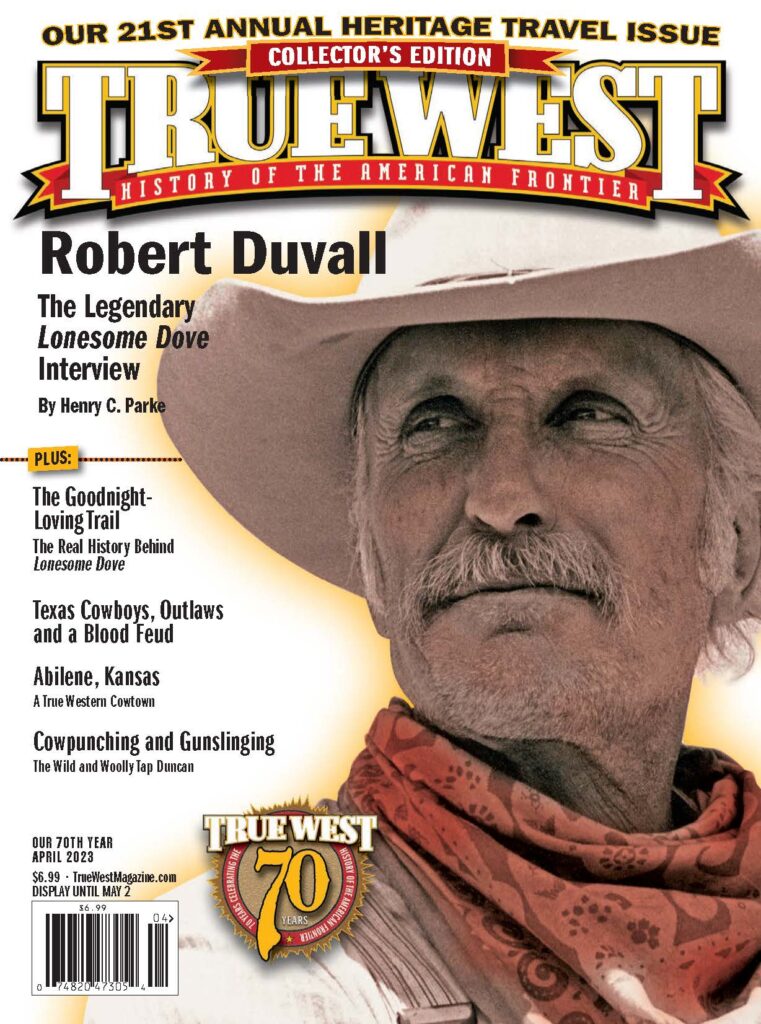

At True West magazine, 70 years since our first issue, we still believe there is no better way to experience the American West than to pack your bags, load up your car and hit the road.

In this 21st edition of our travel issue, we feature getaways written by six seasoned Western writers whose passion for the West and their home states is infectious. We invite you to pull out your maps—and dreams—and take a road trip to Arizona, Missouri-Arkansas-Oklahoma, Montana, South Dakota, Texas and/or Wyoming. We know you will make dreams come true and will start planning your next road trip as soon as you return home!

—Stuart Rosebrook

Wyoming

Discover the cattle ranching history of the Cowboy State on three heritage travel adventures.

By Candy Moulton

Cattle Trails to the Bighorn Basin

Scotsman Peter McCulloch immigrated to the United States in 1853, spent time in Boston and St. Louis, and served during the Civil War in the Union Army with the Missouri Mounted Volunteers, often carrying dispatches throughout Missouri and Arkansas and later becoming a wagon boss. He then worked with a survey party staking out the transcontinental railroad for the Union Pacific Railroad in Nebraska, but by 1864 he was at Fort Bridger.

Judge William A. Carter, whose family roots are at Carter’s Grove in Virginia, had served as the post sutler at Fort Bridger, and his presence in the Bridger Valley led him to begin raising cattle for his Carter Cattle Company. Peter McCulloch became the range foreman for Carter’s operation, establishing himself as a top-notch cowboy and manager.

In 1879, McCulloch ramrodded a crew that trailed 3,800 head of Carter cattle into the Bighorn Basin. McCulloch took the cattle from the Bridger Valley near Evanston and Fort Bridger across the Red Desert to South Pass, through the Lander area and across the Wind River Basin before continuing into the Bighorn Basin, where he established a headquarters west of where Cody would eventually be established, on Carter Creek, named for his boss.

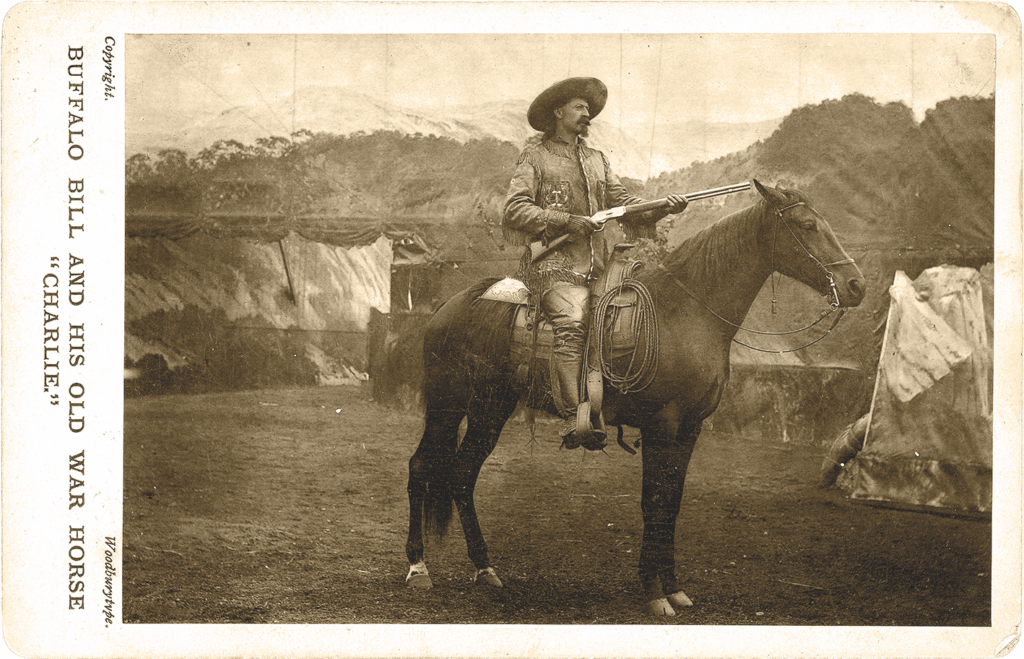

True West Archives

McCulloch and Carter had effectively expanded Wyoming’s cattle operations across the western half of the Wyoming Territory. The McCullough Peaks, east of Cody, well known as the habitat for one of Wyoming’s wild horse herds, are named for Peter McCulloch, but, as often happens, the spelling is different.

Some of the earliest livestock in the Upper Green River Basin around Pinedale and Big Piney were cattle herds trailed in from the west: Nevada and Oregon. The Green River Drift—a cattle trail in use since the 1890s to move cattle between summer and winter ranges—is a 58-mile-long route that has been on the National Historic Register since 1913. The Drift is still used by members of the Green River Cattle Association and crosses both public and private land. History of the ranching and homesteading culture of the Upper Green is interpreted at the Sommers Homestead Living History Museum north of Pinedale (open Friday through Sunday during the summer). Restored buildings include the 100-year-old two-story log homestead house, the shop, log icehouse, underground cellar, log bunkhouse, meat house, log barn and historic outhouse.

Gates Frontiers Fund Wyoming Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress

Dubois

A gateway to Jackson Hole, Grand Teton National Park and Yellowstone National Park, Dubois maintains its small-town persona. The area is known for its Whiskey Mountain herd of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep. Learn more about the sheep at the National Bighorn Sheep Center. The early ranching history of the area is highlighted at the Dubois Museum, Wind River Historical Center. Dubois has evidence of visits by Butch Cassidy, who had ranch property near the town, shopped at Welty’s General Store and did business at the post office.

Encampment, Wyoming

Courtesy Grand Encampment Museum

Gates Frontiers Fund Wyoming Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress

Following the Texas Trail and Nelson Story

Cowboys drove cattle from Texas in 1866 over a route across New Mexico and Colorado that became known as the Goodnight-Loving Trail, named for the two men who forged the route, Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving. They sold their herd to John Wesley Iliff, who became a major cattleman with headquarters in present-day northeastern Colorado by the town of Iliff that he helped establish.

Once Iliff bought that Goodnight-Loving cattle herd in 1868, he pushed the animals on to range even farther north. The Goodnight-Loving or Texas Cattle Trail made its first incursion into Wyoming near Cheyenne. It ultimately extended to the west and north, as cowboys pushed animals across eastern Wyoming and on into Montana Territory.

True West Archives

The Texas Cattle Trail passed near the present communities of Pine Bluffs, Cheyenne, Chugwater, Lusk, Moorcroft and Sheridan. There are markers to the trail near Lusk on U.S. 18/20, along Highway 387 west of Wright, and in Moorcroft.

In a separate cattle drive, Nelson Story in 1866 brought a cattle herd from Texas through Kansas and along the Oregon Trail to Fort Laramie. There he began following the route to Montana along the hotly contested Bozeman Trail—a trail that Lakota and Northern Cheyenne tribal members resisted because it was an incursion into their territory.

Candy Moulton

By the time Story’s herd arrived at Fort Phil Kearny, one of the three forts established to provide protection to travelers along the Bozeman Trail, he was told not to go any farther due to attacks by tribal warriors. Story did not heed the warnings and pushed his herd on. They crossed the Yellowstone River and turned west, finally reaching Virginia City, Montana Territory’s prominent gold camp, in early December.

Less than a month later the Lakota struck a major blow against the frontier army, when they lured soldiers led by Lt. William J. Fetterman over Lodge Trail Ridge just north of Fort Kearny and into the decisive battle that led to the deaths of Fetterman and the 80 men who were in his command. In less than a year the military withdrew from the region, and Little Wolf, of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, burned Fort Kearny.

More than a decade after Nelson Story took his herd through the Powder River Basin and along the Bozeman Trail to Montana, John B. Kendrick brought a herd of Texas cattle to the area, ending his drive in 1879 in Sheridan, where he established the Kendrick Cattle Company. He later became Wyoming’s governor and then senator and built a spectacular mansion home for his family, that is now the Trail End State Historic Site.

True West Archives

Sundance

Harry Alonzo Longabaugh spent 18 months in the town jail after he pleaded guilty to stealing a horse, saddle and gun from an employee of the VVV Ranch near Sundance, Wyoming. His time in the jail ended when Wyoming Governor Thomas Moonlight pardoned him, but there was a lasting connection to the town when he became known as the Sundance Kid. Learn more about Longabaugh’s time in the town that gave him his better-known name with a visit to the Crook County Museum.

Sundance, Wyoming

Courtesy Wyoming Tourism

Cherokee Cattle Trails

The Cherokee Trail, stretching some 900 miles from Fort Gibson (on the Texas Trail) to Fort Bridger, became the major thoroughfare to the West, and was a route to California, making it the longest branch of the California National Historic Trail. About 100,000 head of livestock traveled over this trail prior to 1861. Cattle drives on its route involved cowboys from Arkansas taking cattle to California, and it was also used by Mormons driving herds to Utah.

The first use of the trail took place in 1849, when a wagon train led by Lewis Evans, including Cherokee Indians and gold-seekers from Arkansas traveled across Oklahoma and Kansas to the Santa Fe Trail, which they followed to Bent’s Old Fort and continued west to the site of Pueblo, Colorado, before heading north.

Passing near where Laramie, Wyoming, would be established as a railroad town when the Union Pacific was built nearly two decades later, the travelers then headed west around the north side of the Medicine Bow Mountains and Elk Mountain. They went through the area that later became Rawlins and then across the Red Desert, eventually reaching Fort Bridger to join the main trail to California, even then busy with argonauts intent on getting to the goldfields.

The first cattle drive into North Park Colorado and on into the North Platte and Encampment River valleys of Wyoming was on a different trail the Cherokees forged in 1850. This south branch of the Cherokee Trail took them north of Walden, Colorado, then along the eastern flank of the Sierra Madre, across the Encampment River just north of Riverside, and west to pass near the present-day town of Baggs and on west across the Red Desert to Fort Bridger. Follow their route by taking Highway 230 west out of Laramie to Encampment, Highway 70 (open late May to late October) to Baggs, then head north on Highway 789 to Interstate 80 and follow it west to Fort Bridger.

This southern branch used by the Cherokee people was short-lived, but the northern Cherokee Trail across Wyoming eventually became the same route as the Overland Trail, a major pathway used by travelers, particularly in the 1860s during the last significant years of overland wagon travel, before the Union Pacific Railroad arrived, giving travelers another way to cross the West.

True West Archives

Evanston

The Union Pacific Railroad construction pushed across Wyoming in 1867-69, spawning tent cities and leading to the establishment of Wyoming Territory. Evanston might have been just one of many end-of-tracks towns that grew quickly and then disappeared, but the Union Pacific later determined it would become a headquarters community. This gave it permanence, and the community still celebrates its diverse history at the Unita County Museum and with the unique collections of the Chinese Joss House Museum.

Candy Moulton hangs her hat near Encampment Wyoming, within sight of ruts on the South Branch of the Cherokee Trail.

Where History Meets the Highway

Museums

Cattle Trails to the Big Horn Basin: Fort Bridger State Historic Site, Fort Bridger; Sommers Homestead Living History Museum, Pinedale; Museum of the Mountain Man, Pinedale; Museum of the American West, Lander; Meeteetse Museum, Meeteetse; Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody

Texas Trail and Nelson Story: Cheyenne Frontier Days Old West Museum, Cheyenne; Messinger’s Old West Museum, Cheyenne; Nelson Museum of the West, Cheyenne; Pioneer Memorial Museum, Douglas; Stagecoach Museum, Lusk; West Texas Trails Museum, Moorcroft; Crook County Museum, Sundance; Jim Gatchell Museum, Buffalo; Fort Phil Kearny State Historic Site, Buffalo; Trail End State Historic Site, Sheridan; King’s Saddlery and Don King Museum, Sheridan

Cherokee Cattle Trails: Wyoming Territorial Prison State Historic Site, Laramie; Laramie Plains Museum, Laramie; Grand Encampment Museum, Encampment; Little Snake River Valley Museum, Savery; Carbon County Museum, Rawlins; Fort Bridger State Historic Site, Fort Bridger; Bear River State Park, Evanston

Good Eats & Sleeps

Eats: Rib & Chop House, Cheyenne; O’Dwyers Public House, Laramie; The Bear Trap, Riverside; 307 Grill, Encampment; Bon Rico, Evanston; The Busy Bee Café, Buffalo; Mint Bar, Sheridan; The Invasion Bar and Grill, Kaycee; Bearlodge Bakery, Sundance; Cowboy Café, Dubois; The Irma Hotel, Cody; Cowboy Bar, Pinedale; The Rifleman Club Bar, Rawlins; Su Casa, Sinclair; Longhorn Saloon & Grill, Sundance

Sleeps: Little America, Cheyenne; Historic Plains Hotel, Cheyenne; Spirit West River Lodge, Encampment; Occidental Hotel, Buffalo; Sheridan Inn, Sheridan; Mill Inn, Sheridan; Saratoga Hot Springs Resort, Saratoga; Hotel Wolf, Saratoga; Best Western Premier Ivy Inn, Cody; Chambers House Bed & Breakfast, Pinedale; Virginian Hotel, Medicine Bow

Dude Ranches: Eatons’ Ranch, Wolf; A Bar A Ranch, Encampment; Vee Bar Guest Ranch, Laramie; Crossed Sabres Ranch, Cody; Blackwater Creek Ranch, Cody; Lazy L&B Ranch, Dubois; Triangle C Ranch, Dubois; Medicine Bow Lodge & Guest Ranch, Saratoga; Hideout Lodge & Guest Ranch, Shell; Paradise Guest Ranch, Buffalo; Triangle X Ranch, Moose; Spotted Horse Ranch, Jackson

Montana

Discover the historic trails that built the Big Sky State.

By Quackgrass Sally

Courtesy Carol Highsmith Archives, Library of Congress

Trails

Montana has always been a land of many trails. For centuries the Native peoples crisscrossed these lands on game trails their ancestors had followed, finding food and campsites in its mountains, valleys and plains. When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the Corps of Discovery trekked west and reached this region in 1804-06, they were the first White explorers to use these routes and see these lands. Clark’s journal noted that the fertile landscapes were made all the more wondrous by the abundant rivers, lakes and streams which fed it. Quickly on their heels, fur trappers and traders followed that trail until the 1840s, when the dwindling supply and demand for beaver no longer drew them.

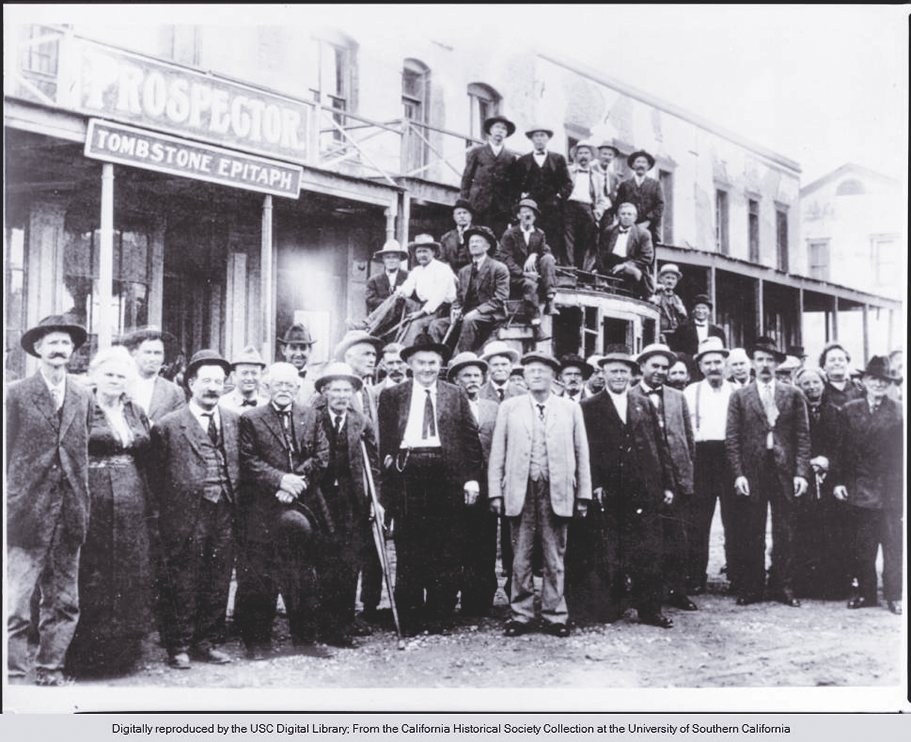

Courtesy USC Digital Collections

Gold was discovered in Virginia City, Montana, in 1863, and soon a flow of gold miners were following the Bridger Trail (Bridger Road), which connected the Oregon Trail to the goldfields of Montana. The influx of people wanting to head northwest prompted John Bozeman and John Jacobs to scout out a new route from central Wyoming to Montana. This new Bozeman Trail created a more direct route through the Powder River country, the region of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow and Arapaho people, who quickly resented the growing stream of White settlers into their lands. Raids on the settlers grew and unrest was brewing between the cultures.

In 1864, Col. William O. Collins, the commandant at Fort Laramie, became worried about the conflicts along the Bozeman Trail. He requested Jim Bridger lead a party of settlers along the new route to the gold mines in what was now Montana Territory. Over that spring and summer, 10 wagon trains made the trip, two guided by Bridger himself. The following year the unrest along the Bozeman Trail grew, forcing Maj. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge to order Brig. Gen. Patrick E. Conner to lead the first Powder River Expedition to end the raids along the trail. For years the unrest continued, reaching a head in 1876, when the Lakota and Cheyenne people vanquished Lt. Col. George A. Custer and the U.S. Army at the now famous Battle of Little Bighorn.

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections

Cattle

Trails brought miners and settlers to the Montana Territory but they also brought the cattlemen. One of the first major cattle drives to Montana was made by Nelson Story Sr. in 1866. Having been a gold miner himself and after his “big hit” at Alder Gulch, in Virginia City, Montana, years earlier, Story knew the demand for fresh meat in the goldfields was as intense as the hunt for gold.

With the end of the Civil War and the economy of Texas devastated, Story decided that with the extreme number of cattle roaming all over Texas, he could gather up a large herd for very little expense. Using his mining profits, it is estimated he spent nearly $10,000 for approximately 1,000 head of Texas longhorns (some say it might have been up to 3,000 head) and was determined to herd them northward along the Bozeman Trail to the goldfields of Montana.

When Story and his wranglers reached Fort Phil Kearny, between what is now Buffalo and Sheridan, Wyoming, the U.S. Army demanded Story quit his drive north because of the growing unrest with the Indians. The newly seasoned Texan trail boss was determined to continue moving his herd and disregarded the Army’s orders. Throughout the rest of the trail drive, Story had encounters with Lakota warriors. During one skirmish, a man was killed, but in December 1866, the herd arrived in what is now present-day Livingston, Montana. Story soon established a thriving cattle business, selling to hungry gold miners at 10 times the Texas prices. By 1870, Nelson Story had built himself a ranch in the Paradise Valley of Bozeman, becoming the leading cattleman on the open-range of the northern plains.

When the Northern Pacific Railroad arrived in Montana in 1881, the earlier hardships of ranching greatly improved, and Nelson Story used his cattle fortune to invest in banking, mercantile and grain. The Story Flour Mill opened in 1882, producing 100 bushels a day of fine Montana flour and became a major source of flour for the U.S. Army at Fort Ellis. He later supplied flour to the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana, which helped make him the first millionaire of Montana. By 1884 the Montana Stockgrowers’ Association was formed, and before long, with the use of barbed-wire fencing, the vast open ranges were no more. Land preservation and smaller ranch herds became the norm, and in 1889, the territory of Montana became a state.

Butte, Montana

Courtesy James St. John, Creative Commons

Tobacco Gold

On a sunny May afternoon in 1863, several men were camping along a small stream surrounded by groves of alder trees. William Fairweather and Henry Edgar decided to prospect and see if they could pan enough gold to buy some tobacco. When the first small pan showed over two dollars’ worth of gold, the men knew the gulch had the makings of a good claim. This discovery of gold in Alder Gulch was the foundation of the town of Virginia City, one of the biggest boomtowns in Montana Territory.

Word of gold in Montana spread, and soon miners and fortune seekers alike flocked to the territory. The hillsides of alders were clear-cut for building materials and fuel, and the town grew. In 1864 the city was the most populated place in Montana with over 5,000 inhabitants. At its peak, it is estimated 10,000 people lived in what they referred to as “Fourteen-mile City” for all the small settlements that lined the gulch.

By 1865, Virginia City was designated as the new Territorial capital of Montana. It became a hub for activities and was dubbed the “Social City,” where diverse supplies and people came together. A wide variety of businesses prospered, and over 1,200 buildings lined its streets. In the early years, Alder Gulch and Virginia City included Euro Americans, Indians, Mexicans and African Americans. By 1870, about one third of the population of Virginia City was Chinese.

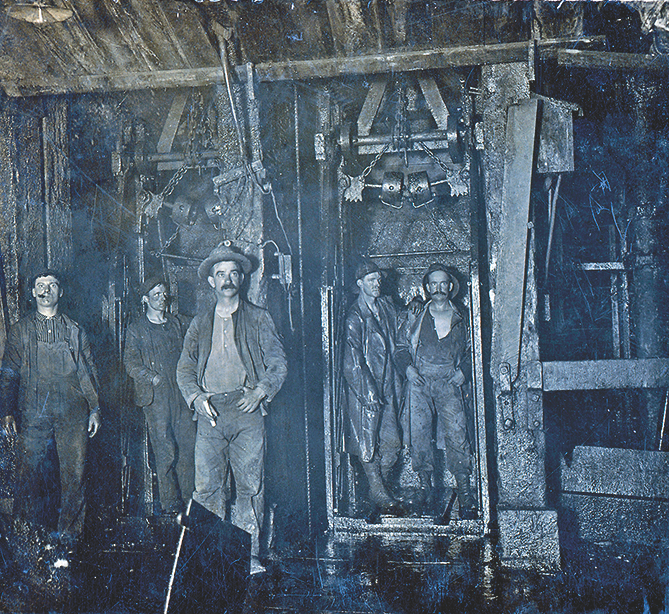

At first, the mining around Virginia City was done using hand tools, sluice boxes and pans. Lode, or hard-rock mining, was also taking place in the upper part of Alder Gulch, but it took much more man power and was much harder than the placer mining and never seemed to be as productive. (Hard-rock mining is generally defined as the extraction of metals using underground mining methods.) By 1867, the norm was hydraulic mining, in which jets of pressurized water from hoses washed down the hillsides of dirt. Piles of rocks and hydraulic cuts filled the area. In 1898 large floating dredges chewed up the ground, leaving behind distinctive tailings and dredge ponds. Many communities along the dredges’ paths in the gulch were completely destroyed, but Virginia City was never dug up, as its foundations were not built on gold-bearing gravels. The railroad’s arrivial into Montana brought with it an incresed demand for gold and silver. A branch-line railroad reached Alder Gulch in 1901, but it did not extend the 10 miles to Virginia City because the tracks would have interfered with the dredging operations.

Original Mine, Butte, Montana

Courtesy SMU DeGolyer Library

Mining in Alder Gulch had long-reaching effects on settlement and the trails of the West. Its gold contributed to the expansion of transportation and the national economy. It wasn’t until the Virginia City newspapers announced the discovery of gold in Last Chance Gulch (Helena, Montana) that many of its people moved farther north to make their fortunes. The territorial capital was relocated to Helena, and before long, construction in Virginia City had declined, with many of its older places falling into ruin.

In 1899, Henry Edgar, one of the men who first discovered gold at Alder Gulch, along with members of the Montana Historical Society (established in 1865) decided that the history of Virginia City needed to be preserved. By 1907 the town was well into fullfilling that wish. Five road agents buried at Boot Hill were identified, reburied and given new headstones. Preservation continued with the Thompson-Hickman Museum, built in 1918. With the growing number of automobile travelers in the 1920s, tourists started to arrive and learn the story of the Alder Gulch area. In 1928 a large marble marker was placed at the spot where Henry Edgar and his partner found their tobacco gold. Today, Virginia City is considered one of the best preserved placer mining camps of the 1860s West. With its preserved architecture and historical significance, Virginia City has gained national recognitaion with almost 500,000 visitors annually.

Main Street, Virginia City and the Thompson- Hickman Museum will let you step back in time to discover this Montana gold boomtown. Visit historic buildings filled with thousands of preserved artifacts from daily life in a mining town. Enjoy the Brewery Follies and the Virginia City Players for fun entertainment for the whole family.

Courtesy Montana Office

of Tourism

Montana Copper

With the backdrop of the Rocky Mountains’ Continental Divide, Butte began as nothing more than a camp of miners, looking for gold and silver in the late 1800s. The growing numbers of successful miners and those who followed had the town enlarging at an almost daily rate. In addition, Butte businesses were creating a downtown district which soon was referred to as “Uptown Butte.” A huge fire in 1879 devastated the city, burning down the entire central business district. When its citizens and the city council decided to rebuild, a new law went into order, requiring all new buildings in Uptown Butte to be built of brick or stone. (Most of these buildings are still standing in Butte today.)

After the turn of the century, gold and silver were still readily mined, but it was the introduction of elecricity that expanded the copper mining. This growth created the bustling city’s nickname: “Richest Hill on Earth.” By the 1890s, Butte was reported to supply over 25 percent of the world’s copper and up to 50 percent of the United States’ copper. It became the largest city between Chicago and San Francisco, with over 100,000 people.

From the beginning, Butte’s mining successess drew immigrants from all over the world. By 1900, one-fourth of the city’s residents were Irish. The wide mixture of cultures gave Butte a rather wild reputation, with its numerous saloons, as well as Mercury Street’s “Venus Alley” or red-light district. Butte became famous for its variety of ethnic foods, and diners could find Scaninavian lefse, Cornish pastys and Irish stews and meats in its dining places. Along with the Irish, Butte was home to a large number of Chinese immigrants. One famous establishment in Butte, the Pekin Noodle Parlor, is still the oldest continuously running Chinese restaurant in America.

In 1899, Standard Oil Company, wanting to invest in the area, purchased numerous mines and smelters. The conglomerate was called the Amalgmated Copper Mining Company, which soon became Anaconda Mining Company. Throughout the 1900s this company maintained mining operations in Butte, merging into the Arco Company, until all mining operations stopped in 1983. Today, visitors can learn about the history of Butte and mining in Montana at The World Museum of Mining, which is an amazing stop in which to explore the history of mining in the state. With over 50 exhibit buildings and an underground tour, it offers a glimpse into this unique industrialization of Montana and America. Wander through a turn-of-the-century mining town and visit over 50 buildings, from the 100-foot-high headframe to the heart of Hell Roarin’ Gulch. Displays and exhibits focus on mining and the related culture that made Butte. Enhance your visit by taking an underground guided tour into the depths of the Orphan Girl Mine to learn the history of mining, and see the Orphan Girl vein and the original workings of the mine.

Quackgrass Sally is a working ranch wife and freelance author in Montana. She writes about the West from her own experiences, having ridden her horse and driven her covered wagon thousands of miles along the Western historic trails.

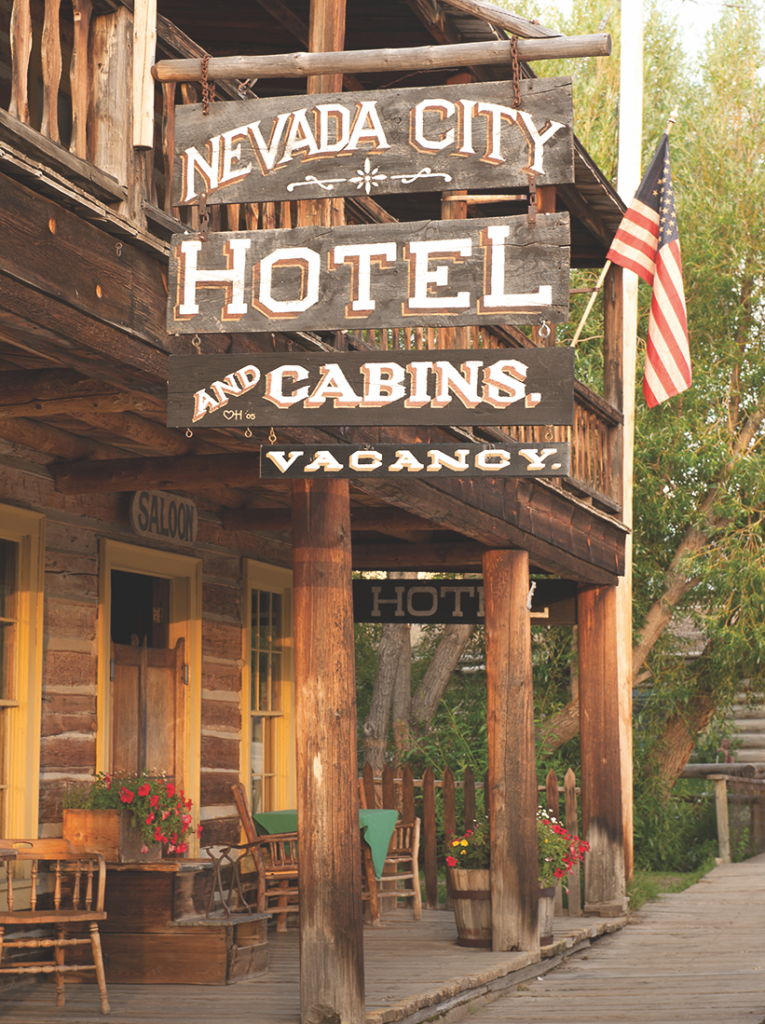

Nevada City, Montana

Courtesy Montana Office of Tourism

Where History Meets the Highway

Museums

Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman; Gallatin History Museum, Bozeman; Bozeman Art Museum, Bozeman; World Museum of Mining, Butte; Madison Valley History Museum, Ennis; Montana Historical Society Museum, Helena; C.M Russell Museum, Great Falls; Headwaters Heritage Museum, Three Forks; Three Forks Headwaters Railroad and Trident Heritage Center, Three Forks; Yellowstone Gateway Center, Livingston; Livingston Depot Center, Livingston; Western Heritage Center, Billings; Yellowstone County Museum, Billings; Carbon County Museum, Red Lodge

Good Eats & Sleeps

Eats: Palace Restaurant & Saloon, Virginia City; Bale of Hay Saloon, Virginia City; Bacchus Pub, Bozeman; The Molly Brown Bar, Bozeman; Pekin Noodle Parlor, Butte; The Silver Dollar Saloon, Butte; Old Saloon, Emigrant; Gold Bar & Western Bar, Helena; Celtic Cowboy, Great Falls; Timber Bar & Grill, Big Timber; The Murray Bar, Livingston; Montana Club, Billings

Sleeps: Fairweather Inn, Virginia City; Nevada City Hotel, Virginia City; Kimpton Armory Hotel, Bozeman; Copper King Mansion, Butte; The Barrister Bed & Breakfast, Helena; The Jeffers Inn, Ennis; Historic Murray Hotel, Livingston; Northern Hotel, Billings

Dude Ranches: Diamond J Ranch, Ennis; Mountain Sky Guest Ranch, Emigrant; Hubbard’s Six Quarter Circle Ranch, Emigrant; Rocking Z Guest Ranch, Wolf Creek; Sweet Grass Ranch, Big Timber; Elkhorn Ranch, Gallatin Gateway; Nine Quarter Circle Ranch, Gallatin Gateway; Lone Mountain Ranch, Big Sky

Arizona

Discover the Grand Canyon State’s rich history of ranching, mining and railroads in its small towns.

By Stuart Rosebrook

With the growth of Las Vegas, Nevada, many visitors fly into the city that never sleeps to begin a tri-state Southwestern adventure in the Silver State and to its neighbors, Utah and Arizona. But for those intending to visit communities in Central and Southern Arizona, Phoenix is their hub. In either case, heritage travelers to Northern Arizona from Las Vegas or Phoenix will soon discover in Kingman or Williams, respectively, one of the most historic routes of Western travel: Route 66.

Nevada City, Montana

Courtesy Montana Office of Tourism

Northern Arizona

A list of the icons of the West usually is full of the famous and infamous, mustangs and buffalos, cowboy hats and boots, stately saguaros and giant redwoods. But, right in the middle of that list will always be a highway that sparks international recognition upon its utterance: Route 66. And Arizona just happens to be the state with the longest stretches of the historic Mother Road. From the California to New Mexico boundaries, Route 66 travelers will discover the history of America in the West.

Long before the first stretch of U.S. Highway 66 was excavated and paved, the route we know today at Route 66 and Interstate 40 across Northern Arizona had been traversed for centuries. Water determined routes in the arid climate, and the construction of Beale’s Wagon Road, the Santa Fe Railway, Route 66 and I-40 all followed the water. Long before the latter two, the Army, ambitious settlers and the railroad set up camps, way stops and towns at key sources of water. Driving in from Las Vegas, travelers to Northern Arizona can arrive in Arizona on I-40 via U.S. 95 through Needles, U.S. 93 to Kingman (via the Hoover Dam, a highly recommended stop and tour), or take the long way: U.S. 95 to I-40 to Arizona 10 near Topock for a great side road to the historic mining town of Oatman (watch out for the donkeys!).

Kingman, Arizona

Courtesy Mohave Museum of History and Arts

For travelers coming from Las Vegas, Kingman on I-40 is the first major stop in Northern Arizona. Those feeling nostalgic for the bygone days of the U.S. highways before the interstates, should schedule a weekend in Kingman to visit its Route 66 museums, shops and restaurants. Check in at the Kingman Visitor Center first to get an introduction to the city and local happenings. While in town, before heading north and east on Old Route 66, stop by the local Mojave History and Art Museum, the town’s railroad museum and Bonelli House. Before you go, plan your stay in Kingman at ExploreKingman.com.

From Kingman to Williams, travelers have two route options: either 115 miles on I-40 or the scenic old Route 66, which, if you have the time, could easily include an overnight or two in Peach Springs on the West Rim of the Grand Canyon on the Hualapai Indian Reservation. The drive on 66 through the small villages of Hualapai, Anteres, Hackberry, Valentine, Crozier, Truxton and Seligman is an enjoyable, slow trip into the past, including an old-fashioned hamburger and ice cream at Delgadillo’s Snow Cap Drive-In in Seligman.

Gateway to the Grand Canyon

In 1901, the Santa Fe Railway opened its rail line to its luxurious El Tovar Hotel on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Ever since, Williams has been known as the Gateway to the Grand Canyon. With the construction of Route 66 in the 1920s, travelers would arrive in Williams by car or passenger train and enjoy the friendly, Western atmosphere of the mountain town before taking the train to and from the natural wonder. In 1989, after a 21-year hiatus, the Grand Canyon Railway began operating daily, and once again, travelers could park and stay in Williams and take the train to the national park. The modern railway even has package deals for visitors to stay in Williams and at the Grand Canyon, a classic way to enjoy both the fun-filled town and the park.

Williams is a four-season city and has shopping, restaurants and hotels for all tastes and budgets. The summertime is filled with events, including parades, rodeos, and Route 66 auto rallies. The Grand Canyon Railway has its own special events including Steam Saturdays, when excursions on the first Saturday of the month, March to September, are pulled by a restored steam locomotive. In the winter, the very popular Polar Express train excursions in November and December are for all ages. A great way to plan your stay in Williams is to contact the Williams Visitor Center at ExperienceWilliams.com.

Prescott, Arizona

Stuart Rosebrook

Central Arizona

Arizona’s Yavapai and Maricopa counties are two of the largest in the country. Visitors who want to experience almost every aspect of the Grand Canyon State will find it in these historically, geographically and culturally diverse counties. From day trips to weeks-long adventures, consider three towns as the perfect headquarters for experiencing all these counties have to offer: Prescott, Wickenburg and Cave Creek.

Prescott

Nicknamed “Everybody’s Hometown” by an intrepid booster, Prescott offers a friendly, mile-high mountain atmosphere and historic downtown, welcoming millions of visitors annually.

The original territorial capital of Arizona, Prescott almost immediately became an important crossroad of commerce in the fledgling territory. Today, Prescott is the Yavapai County Seat and one of the state’s most significant commercial, educational and tourism centers.

The 136th annual Prescott Frontier Days and the World’s Oldest Rodeo is scheduled for June 28-July 4. Get your tickets early, as it quickly sells out. Those who love a parade will want to be in town for the annual Frontier Days Parade on July 1. This year’s theme is “Dances with Bulls” and honors the skills of the rodeo bull fighters.

Prescott, with its historic downtown plaza, is also an outdoors, festival and history lovers’ destination. Because

it is surrounded by the beautiful Bradshaw Mountains and within driving distance to the historic mountain mining town of Jerome, outdoor enthusiasts flock to Prescott year round. Almost every weekend from May to October, the Yavapai County Courthouse Plaza is host to a festival, while in December, Prescott transforms itself into Christmas City.

Museums that celebrate the community’s history and heritage are must-visits when in the mountain town. Sharlot Hall Museum, which will celebrate its centennial in 2028, is the state’s premier terri-

torial living history center. Downtown, the Prescott Western Heritage Center provides a great introduction to the county’s history and nonprofit volunteer history organizations. The Phippen Museum has the state’s best cowboy art collection, and the Indigenous Peoples Museum is the perfect stop at which to learn more about Arizona’s original residents.

Start at Prescott’s Chamber of Commerce or go to Prescott.org to plan a vacation to the mile-high city that proves every day why it’s “everybody’s hometown.”

Wickenburg

Located in the beautiful high Sonoran Desert of Maricopa County, Wickenburg is one of the oldest communities in central and northern Arizona. Founded in 1863 after the discovery of gold in the area, the mining and ranching town was built along the banks of the Hassayampa River and quickly grew into one of the territory’s most important crossroads and commercial communities. Over 150 years later, Wickenburg is still an important hub of economic activity for the county, best known today for its Western ranch resorts, ranching, roping and arts community.

When I visit Wickenburg, I love to park downtown and walk around the highly walkable city. Enjoy the local shops, art galleries and restaurants while making time to visit the world-class Desert Caballeros Western Museum. One of the most popular and well-attended museum events is the annual “Cowgirl Up! Art from the Other Half of the West, Invitational Exhibition & Sale,” which is now in its 18th year and will be on exhibit from March 31 to September 3, 2023. If you love festivals, parades and rodeos, make plans to attend the 75th Annual Rush Days and Senior Pro Rodeo next February.

Planning a visit to Wickenburg? Go to OutWickenburgWay.com for all the latest events and information, or stop in at the Chamber of Commerce and Visitor Center in the historic Santa Fe Railway station on Frontier Street.

Cave Creek

In Maricopa County, Cave Creek may be one of the most eclectic and fun towns to visit and live in. Abutting Tonto National Forest on the far northeastern end of the suburban sprawl of the Valley of the Sun, the once isolated ranching and mining town is a mecca for horse lovers, artists, bikers, tourists, sports lovers and even a few miners. Despite the summer heat, Cave Creek is a four-season destination as its elevation and low-density desert community is always about 10 degrees cooler than downtown Phoenix.

The core of downtown Cave Creek is walkable and bikeable between antiques shops, restaurants, bars and art galleries. But don’t be surprised if you have to dodge some road apples along the way, because locals still ride their horses into town and tie them up at their favorite watering holes. A great way to enjoy the town’s Western heritage is at the annual Cave Creek Rodeo, held in March.

The Cave Creek Museum celebrates the town’s Western past and provides a good overview of the community’s mining, ranching and cultural past and present. The funky town is well-known for its popular watering holes El Encanto, Tonto Bar & Grill, the Horny Toad, the Hideaway and Buffalo Chip Saloon and Steakhouse, but don’t miss a meal or drink at the local gems: Janey’s, Indian Village, Z’s House of Thai and the Grotto Café.

Cave Creek’s Visitor Center is a great place to start when visiting the desert burg, and the town’s website CaveCreekAZ.gov carries all the latest information on local hotels, restaurants, shops, entertainment and upcoming events.

Southern Arizona

Like many Western states, Arizona’s economy was built on the strength of its natural resources. From the first Spanish settlements in southern Arizona in the late 17th century to the present day, rich veins of silver, gold and copper, especially copper, led to major and minor mining operations across the region. Many of the historic Arizona mining settlements across southern Arizona can still be visited today and enjoyed for their history, culture and natural beauty.

Tombstone

Is there an Old West town in America with greater renown than Tombstone? I would dare say that only Dodge City and Deadwood challenge Tombstone for preeminence as the most infamous and iconic boomtown of the Wild West. “The Town too Tough to Die” is thriving in its role as a living history center of Cochise County’s frontier past. The southeastern Arizona city has established itself as a four-season destination and as one of the most popular communities in the state for historic reenactments and Old West festivals, including Vigilante Days in February, Wild West Days in March, the Rose Festival in April, Wyatt Earp Days in May, Doc Holli-days in August and Helldorado Days in October.

In addition to the festivals, Tombstone has a grand collection of local and state museums. Many visitors start their tours at Boothill Graveyard and then go to the Tombstone County Courthouse State Historic Park, both of which provide strong introductions into the town’s history. Downtown, a tour of the Tombstone Epitaph Museum, the Birdcage Theatre and the O.K. Corral, at minimum, should be scheduled during a long weekend stay. And, of course, don’t miss a chance to enjoy the lively atmosphere at Big Nose Kate’s and the Crystal Palace saloons.

The city’s visitor center at 395 E. Allen Street is always a great place to begin a visit to Tombstone, or better yet, before you hit the road, go online to DiscoverTombstone.com for all the latest information on the Western town.

Bisbee

Like its central Arizona kin, Jerome and Prescott, Bisbee is a historic testament to Arizona’s territorial mining heritage. But while the first settlers in Prescott had gold fever, it was silver and copper that led to the founding of Bisbee. The owners of the Copper Queen mine assayed a rich vein of copper in 1880 and for 95 years the mine operated as one of the most productive in the state and country.

When visitors book themselves into one of the local hotels, inns and bed and breakfasts in the mile-high border city they will be able to easily immerse themselves in the rich history of Bisbee. The highly walkable historic district (steep for some, so driving is an option for the higher reaches of the city) is filled with great shops, restaurants and bars. The historic entertainment district, the Queen Mine and Bisbee Mining and Historical Museum are all walking distance from each other, while the nearby communities of Naco and Warren (don’t miss a visit to the historic baseball field) are a short drive away.

A trip to Bisbee should not be considered complete without a stop at the Bisbee Mining and Historical Museum and taking the Queen Mine tour. The docents who take you underground on little trains are usually retired miners and when they ask you to turn off your headlamps, the darkness and stillness of the mine are truly remarkable and an experience you won’t soon forget.

Want more information on visiting Bisbee? Stop by the visitor center or go to DiscoverBisbee.com to plan your tour.

Arizona and New Mexico Railway Station Clifton, Arizona

Courtesy Road Travel America

Clifton

Clifton, like Tombstone and Bisbee, was founded in 1873 because of the rich ores in the neighboring mountains and drainages of the San Francisco River and its tributaries. Copper soon became the dominant ore of the local mines of the Greenlee County boomtown. Mines, smelters and railroads were built, and the district became—and still is—one of the richest copper mining communities in North American history. In the 1920s, the Coronado Trail, U.S. Highway 191 (originally U.S. Highway 666) connected Clifton with the White Mountains of eastern Arizona. Ever since, the scenic highway (aka the Devil’s Highway) has been renowned equally for its switchbacks and natural beauty. It offers one of the great driving experiences in Arizona and the American Southwest.

Today, visitors to Clifton can relax in the historic district of Clifton. Stop in the Visitors Center, where the welcoming staff can guide you to local lodging, restaurants, museums, shopping and outdoor activities. Before you go, learn more at the city’s website, CliftonAZ.com.

Stuart Rosebrook loves the backroads of Arizona and has been writing professionally about the Grand Canyon State for nearly 40 years.

Where History Meets the Highway

Museums

Northern Arizona: Mojave Museum of History and Arts, Kingman; Kingman Railroad Museum, Kingman; Powerhouse Visitor Center, Kingman; Bonelli House, Kingman; Arizona Route 66 Museum, Kingman; Kolb Studio, Grand Canyon National Park; Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff; Riordan Mansion State Historic Park, Flagstaff; Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff; Walnut Canyon Visitors Center, Flagstaff

Central Arizona: Sharlot Hall Museum, Prescott; Indigenous Peoples Museum, Prescott; Phippen Museum, Prescott; Western Heritage Center, Prescott; Fort Verde State Historic Park, Camp Verde; Jerome State Historic Park, Jerome; Tuzigoot National Monument, Clarkdale; Desert Caballeros Western Museum, Wickenburg; Cave Creek Museum, Cave Creek; Spirit of the West: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, Scottsdale; Heard Museum, Phoenix

Southern Arizona: Arizona Historical Society Museum, Tucson; Tombstone County Courthouse State Historic Park, Tombstone; Rose Tree Inn Museum, Tombstone; Birdcage Theater, Tombstone; Tombstone Western Heritage Museum, Tombstone; Tombstone Epitaph Museum, Tombstone; Boothill Graveyard, Tombstone; Gunfighter Hall of Fame, Tombstone; Bisbee Mining & Historical Museum, Bisbee; Queen Mine, Bisbee; Muheim Heritage House Museum, Bisbee; Bisbee Restoration Museum, Bisbee; Fort Bowie National Historic Site, Bowie; Amerind Museum, Dragoon; Rex Allen Arizona Cowboy Museum & Willcox Cowboy Hall of Fame, Willcox; Chiricahua Regional Museum, Willcox; Kartchner Caverns State Park, Benson; Benson Historical Museum, Benson; Fort Huachuca Museum, Sierra Vista; Greenlee County Historical Society, Greenlee

Good Eats and Sleeps

Eats: Mi Lindo Jalisco, Kingman; Mr D’z Rt 66 Diner, Kingman; Delgadillos Snow-Cap, Seligman; Grand Canyon Brewing Company, Williams; El Corral on 66, Williams; Museum Club, Flagstaff; The Palace Restaurant & Saloon, Prescott; Matt’s Saloon, Prescott; Bobby D’s BBQ, Jerome; Spurs Cafe, Wickenburg; Charley’s Steak House, Wickenburg; El Encanto, Cave Creek; Tonto Bar & Grill, Cave Creek; Big Nose Kate’s Saloon, Tombstone; Crystal Palace Saloon, Tombstone; Cafe Roka, Bisbee; Contessa’s Cantina, Bisbee; Big Tex BBQ, Willcox; PJ’s, Clifton

Sleeps: La Quinta Inn, Kingman; Hampton Inn, Kingman; Grand Canyon Railway & Hotel, Williams; Sheridan House Inn, Williams; Little America, Flagstaff; Hotel Monte Vista, Flagstaff; Hassayampa Inn, Prescott; Hilton Garden Inn, Prescott; Jerome Grand Hotel, Jerome; The Conner Hotel, Jerome; Los Viajeros Inn, Wickenburg; Creekside Lodge & Cabins, Mayer; Prickly Pear Inn, Cave Creek; Rancho Mañana Resort, Cave Creek; Allen Street Inn, Tombstone; Boarding House Inn, Tombstone; Copper Queen Hotel, Bisbee; Bisbee Grand Hotel, Bisbee; Dos Cabezas Retreat Bed and Breakfast, Willcox; Clifton Hotel, Clifton

Dude Ranches: White Stallion Ranch, Tucson; Tanque Verde Ranch, Tucson; Elkhorn Ranch, Tucson; Tombstone Monument Ranch, Tombstone; Triangle T Guest Ranch, Dragoon; Rancho Los Baños, Douglas, Arizona and Sonora, Mexico; Cold Creek Ranch, Clifton; Sprucedale Guest Ranch, Alpine; Rancho de la Osa, Sasabe; Rancho de los Caballeros, Wickenburg; Kay El Bar Guest Ranch, Wickenburg; Flying E Ranch, Wickenburg; Stagecoach Trails Guest Ranch, Yucca

Arkansas-Oklahoma-Missouri

Discover the Western Frontier on a tour of three gateway states to the Old West.

By Erik J. Wright

A road trip through the states of Arkansas, Missouri and Oklahoma would quicky prove to nonbelievers that the violent ways of the frontier flourished here, too. While the thick underbrush, tall trees and rolling hillsides conflict with the popular image of the Western United States, the three gateway states embody the spirit and the history of the Wild West.

True West Archives

Arkansas

Beginning in the state’s far northeast corner near the Missouri bootheel lies Paragould, the county seat of Greene County. For decades, from the 1870s through the turn of the century, Greene County and Paragould was an epicenter of violence and lawlessness. Named for the railroad magnates whose tracks crossed in the middle of town, Paragould is perhaps most famous for the 1909 murder of Charles Gragg by James Trammell. The killer fled to San Francisco and was apprehended before fleeing a second time, never to be heard from again by local authorities. But it turns out that Trammell had escaped to New South Wales, Australia, where he died an old man in 1966. Today, the site of the killing is preserved as a boutique clothing store along a quaint and restored downtown shopping district.

Fort Smith, Arkansas

Courtesy NPS.gov

Traveling southwest past Little Rock you’ll find Hot Springs. If one can look past all the glitz and glamour of the gangster era, the intrepid visitor will discover a rich Western history. It was here that legendary lawman Bat Masterson visited and stayed at the famed Arlington Hotel. In March 1899, Hot Springs Chief of Police Thomas C. Toler and Garland County Sheriff Bob Williams fought for authority over the town’s gambling and the illegal kickbacks that came with it. The feud boiled over with supporters from both factions on Central Avenue in Hot Springs, and five were killed and three wounded.

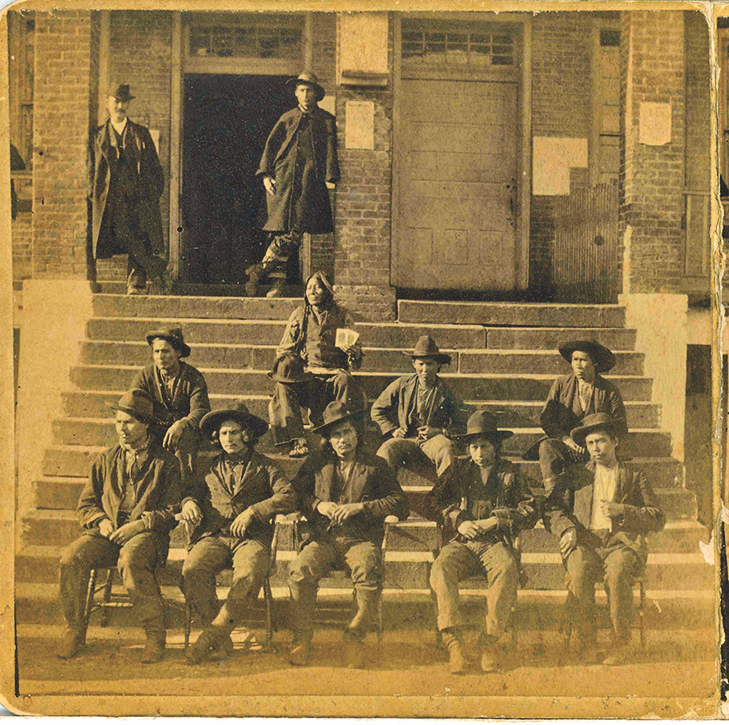

North and west of Hot Springs sits the state’s most famous symbol of frontier law and order: the courtroom of the “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker. Established in 1872, the federal court for the Western District of Arkansas oversaw legal pro-ceedings in Arkansas and the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). A no-nonsense judge, Parker quickly earned a fearsome reputation, and the jail which Parker oversaw soon became known as “Hell on the Border.”

Located nearby is the U.S. Marshals Museum when, once completed, will highlight the history of the marshalcy since 1789. Just north of the museum is Crawford County, Arkansas, and the birthplace of Bass Reeves, the first Black deputy U.S. Marshal west of the Mississippi River. Born into slavery in 1838, Reeves and his family were enslaved by an Arkansas lawmaker and in 1846 moved with his owner to Texas. During the Civil War, it is believed, Reeves escaped and fled to the Indian Territory, where he lived until the 13th Amendment took effect. He returned to Arkansas as a farmer, and in 1875 he was appointed as a deputy U.S. marshal for the Western District of Arkansas because of his ability to speak several Native languages. Reeves served as one of Parker’s most trusted and dependable deputies and worked in that capacity until 1907 with a record of 3,000 felony arrests.

Courtesy NPS.gov

Oklahoma

Outlawry in the Sooner State is well-documented history. From Judge Parker’s deafening gavel on the other side of the border to many outlaw gangs, Oklahoma is sure to please even the most scrupulous Old West buff. From Fort Smith, you can drive just north of Oklahoma City to the city of Guthrie. There, you can visit the gravesite of notorious outlaw Bill Doolin and see where he led a monumental jailbreak of 13 prisoners in 1896. Doolin was killed by U.S. Deputy Marshal Heck Thomas in Lawton, which lies southwest of Oklahoma City.

While in Lawton, visit the famous Quanah Parker Star House in nearby Cache. The house was built by famed Comanche chief Parker many years after his formal surrender in 1875. Once off the warpath, Parker became interested in elevating his status among his fellow Comanches, as well as his reputation with fellow cattlemen in the area, so he built the two-story, 10-bedroom house with large white stars on the roof. Some believe the stars represented, in Parker’s view, the rank of a military general.

Another notable Indian leader has a story at Lawton. The notorious Geronimo, who helped to lead the final Apache resistance until his surrender in 1886, died at Fort Sill in 1909 as a prisoner of war. His grave can be visited, but it is found on the military installation, and visiting the site requires special permitting from the fort’s visitors’ center.

Getting back on the outlaw trail with the Doolin Gang you can travel just a few miles northeast to the crossroads settlement of Ingalls. Here, on September 1, 1893, a running battle occurred when two wagonloads of federal officers tried to catch the gang. Shots were exchanged between the parties, and in the explosive fight an outlaw named Arkansas Tom was killed along with three of the officers.

In the western part of the state near the town of Cheyenne is the Washita Battlefield National Historic Site. Here, on the freezing morning of November 27, 1868, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and four brigades of the 7th Cavalry overran a sleeping village of Cheyenne people and killed an estimated 60 men, women and children. The massacre was part of the overarching fight for control of the Great Plains during the height of westward expansion.

St. Joseph, Missouri

Courtesy St. Joseph CVB

Missouri

Missouri may very well be the cradle of the American frontier. It was from Missouri that the Lewis and Clark expedition left for their journey to the Pacific–and back. Missouri was also home to the American fur trade empire with the St. Louis landing being an eyewitness to many notable figures, including James Beckwourth, Hugh Glass, Manuel Lisa, William Ashley and Andrew Henry. Missouri is also the final resting place of frontier figures William Clark, Samuel Hawken, John Colter, Jim Bridger, William Tecumseh Sherman and Dred Scott. If one can ignore the urban sprawl in places like St. Louis and Kansas City, the sights and sounds of these long-forgotten stories may still be heard.

During the California Gold Rush many Missourians were seen as a lesser class of miner and were often called “Pukes” by those who dismissed their rough and tumble ways. The name may have originated from the number of ’49ers who hailed from Pike County, which is just north of St. Louis along the Mississippi River.

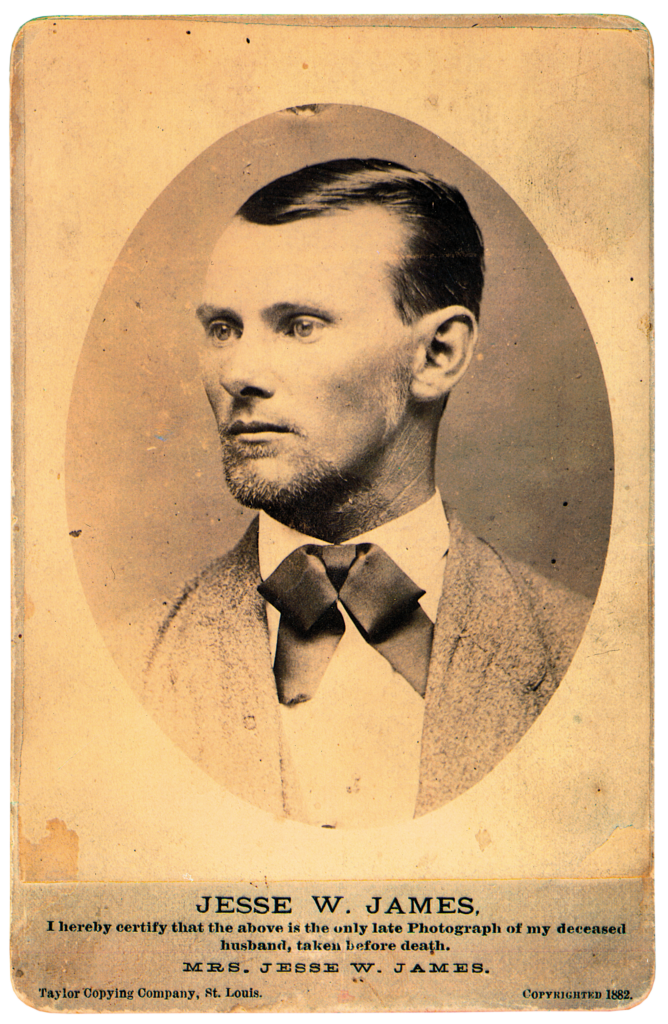

It was from the banks of the Missouri River at Westport Landing that the great migration in 1848 jumped off. Here, thousands of hardy individuals and brave families set their sights west toward Utah, California and Oregon. Missouri was also home to some of the most notorious outlaws in the frontier West. Beginning with the Civil War era, Confederate guerilla leader William Quantrill terrorized the countryside while apprehending escaped slaves. The group under his leadership later became known as “Quantrill’s Raiders” and was responsible for many violent attacks on towns in Missouri and Kansas. Emerging from this chaos of war and scorched-earth tactics were young outlaws, including the James Gang. Jesse and his brother, Frank, were both from Kearney, Missouri, in the northwest part of the state and first gained notoriety after they joined pro-Confederate guerilla groups.

After the Civil War, outlaws like the James boys continued to pillage by robbing trains and banks, and ultimately Jesse James became one of the most symbolic of all the American outlaws. His death at the hands of Robert Ford, also a Missourian, in April 1882 would be avenged in 1892 at Creede, Colorado, by Ed O’Kelley, a native of Harrisonville, which is just south of today’s Kansas City.

True West Archives

Missouri’s most famous contribution to the lore of the violent days of the frontier West may be the unbelievable—but true—duel between James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok and Davis Tutt in the town square in Springfield. In July 1865, just after the end of the Civil War, Springfield was a hub for soldiers, spies and scouts who filled that city’s gambling halls and saloons. Hickok, who had been on friendly terms with an Arkansan named Davis Tutt, became enraged when Tutt grabbed a prized pocket watch belonging to Hickok for collateral over a gambling debt. Hickok warned him to return the watch, but Tutt refused and the two met in the town square. Shots rang out simultaneously from both pistols at the incredible distance of 75 yards. Tutt dropped from a mortal wound to the chest while Hickok was not wounded. Hickok’s status of frontier celebrity was just beginning when, after the affair, a reporter named George Ward Nicholls from Harper’s New Monthly worked to embolden the story of Hickok for national readers.

A trip through the states of Arkansas, Oklahoma and Missouri would be a family-friendly adventure through time. Load up the car with the kids, snacks and some history books and go off in search of the hidden treasurers of each state’s gems of true Western history.

Erik J. Wright published his first article in True West at age 16. He now serves as the assistant editor of The Tombstone Epitaph and lives in Paragould, Arkansas.

Where History Meets the Highway

Museums

Arkansas: Historic Arkansas Museum, Little Rock; Old State House Museum, Little Rock; Fort Smith National Historic Site, Fort Smith; Fort Smith Belle Grove Historic District, Fort Smith; United States Marshals Museum, Fort Smith; Museum of Native American History, Bentonville; Museum of the Arkansas Grand Prairie, Stuttgart; Historic Washington State Park, Washington; Pea Ridge National Military Park, Garfield; Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park, Prairie Grove; Sultana Disaster Museum, Marion

Oklahoma: Oklahoma History Center, Oklahoma City; National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City; First Americans Museum, Oklahoma City; Cherokee Heritage Center, Park Hill; Chickasaw Cultural Center, Sulphur; J.W. Arms & Historical Museum, Claremore; Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa; Woolaroc Museum and Wildlife Preserve, Bartlesville; Oklahoma Territorial Museum, Guthrie; Three Rivers Museum, Muskogee; Five Civilized Tribes Museum, Muskogee

Missouri: Missouri History Museum, St. Louis; Gateway National Park Museum, St. Louis; Independence Historic District, Independence; National Frontier Trails Museum, Independence; James Farm, Kearney; Ancient Ozarks Natural History Museum, Ridgedale; Arabia Steamboat Museum, Kansas City; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; Westport Landing, Kansas City; Pony Express Museum, St. Joseph; Patee House Museum and Jesse James Home, St. Joseph; Missouri State Museum, Jefferson City; Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield, Republic

Good Eats and Sleeps

Eats:

Arkansas: 1812 Pizza Company, Paragould; The Ohio Club, Hot Springs; McClard’s BBQ, Hot Springs; Doe’s Eat Place, Fort Smith; Riverfront Steakhouse, Little Rock; Rockin’ Pig Saloon, Eureka Springs

Oklahoma: Cattleman’s Steakhouse, Oklahoma City; McClintock Saloon & Chophouse, Stockyards City; Smokin’ Joe’s Stilly, Stillwater; Blue Belle Pizza Parlor & Saloon, Guthrie; Spudder Restaurant, Tulsa

Missouri: Arthur Bryant’s BBQ, Kansas City; The Majestic, Kansas City; O’Malley’s 1842 Pub, Weston; Fox & Fire Barbecue, Kearney; A Little BBQ Joint, Independence; Hank & Aces Pit BBQ, St. Joseph; Sweet Smoke BBQ, Jefferson City; Pappy’s Smokehouse, St. Louis

Sleeps:

Arkansas: White House Inn B&B, Paragould; The Arlington Resort Hotel & Spa, Hot Springs; 1886 Crescent Hotel & Spa, Eureka Springs; Grand Central Hotel, Eureka Springs; Inn at Carnall Hall, Fayettville; Beland Manor Bed and Breakfast, Fort Smith; Capitol Hotel, Little Rock

Oklahoma: The Campbell Hotel, Tulsa; The Mayo Hotel, Tulsa; The Colcord Hotel, Oklahoma City; The Stone Lion Inn, Guthrie; Pollard Bed & Breakfast, Guthrie

Missouri: The Elms Hotel and Spa, Excelsior Springs; Whiskey Mansion Inn, St. Joseph; Silver Heart Inn, Independence; St. Louis Union Station Hotel, St. Louis; The St. George Hotel, Weston

Dude Ranches:

Arkansas: Horseshoe Canyon Ranch, Jasper; Hidden Valley Guest Ranch, Eureka Springs; Double D Lazy J Ranch & Bed, Breakfast & Barn, Perryville

Oklahoma: Wolf Creek Ranch, Pawhuska; Rebel Hill Guest Ranch, Antlers

Missouri: Bucks and Spurs Guest Ranch, Ava

Texas

The Lone Star State celebrates the bicentennial of the Texas Rangers.

By Mike Cox

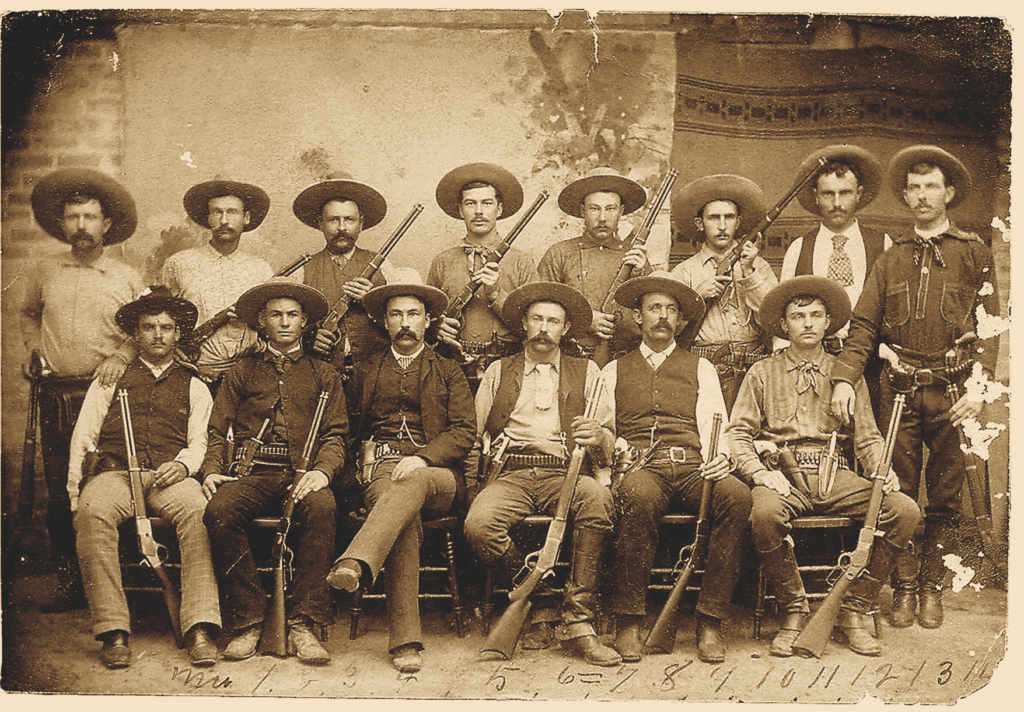

Admired by many, denounced by some, the Texas Rangers trace their 200-year history to a 177-word document penned by Texas colonizer Stephen F. Austin on August 5, 1823. In that document, he said he intended to employ 10 men “to act as rangers for the common defense…”

Considered the Ranger “Magna Carta,” the document was written at Sylvanus Castleman’s log cabin about five miles northwest of present La Grange. Castleman’s place served as de facto headquarters for Austin’s fledgling colony and was the birthplace of the Rangers. To learn more about Castleman and his land, visit the Fayette County Heritage Museum and Archives, 855 S. Jefferson St. in La Grange.

Later in 1823, Austin platted a townsite near the Brazos River and named it San Felipe. For 13 years, the village reigned as the capital of his colony and the social, economic and political hub of Anglo settlement in northern Mexico.

As conceived by Austin, paramilitary companies did “range” his colony in the 1820s, but not until 1835 did the ranging concept become formalized in Texas. That happened at San Felipe when a body called the Permanent Council met there to grapple with two critical issues—a dictatorial Mexican government and the threat of hostile Indian tribes.

Daniel Parker offered a resolution on October 17, proposing a three-company, 70-man standing ranger force. By November, a larger group calling itself a “Consultation” further discussed Parker’s idea. On the 24th the body passed an “Ordinance Establishing a Provisional Government.” Article 9 of an appendage labeled “Of the Military” authorized a “corps of rangers.” For the first time the Rangers became an arm of the government.

San Felipe’s chance of continuing as an important Texas city ended during the 1835-36 revolt against Mexico. After the fall of the Alamo in March 1836, with General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna marching in their direction, residents torched the town and fled eastward. The community never regained its prewar stature but is one of Texas’s most significant historical sites. San Felipe de Austin State Historic Site (220 Second St., San Felipe) features a new museum, interpretive trails and a bronze statue of Stephen F. Austin.

Courtesy Carol M. Highsmith Archives, Library of Congress

On the Ranger Trail

Up the Brazos from San Felipe is the old town of Washington—better known as Washington-on-the-Brazos. A delegation of Texans gathered there March 1, 1836, to formalize the rebellion against Mexico. The next day, meeting in a drafty frame building, the delegates adopted a declaration of independence. Three of the 59 signers were current or former rangers.

A replica of the small structure where that happened is the centerpiece of Washington-on-the-Brazos State Park (23200 Park Road 12, Washington, Texas). Nearby is the Star of the Republic Museum, a facility devoted to the near decade-long history of the Republic of Texas.

In 1833-34, in present Limestone County, the family and followers of Elder John Parker built a split-cedar log stockade with two blockhouses and began farming the adjacent land.

Their compound, Fort Parker, soon figured in one of the classic dramas of American frontier history: the capture of nine-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker and her subsequent rescue by Texas Rangers. Much less known is that before that, the fort served as a rendezvous point for the first government-authorized Ranger force.

Washington, Texas

True West Archives

In the summer of 1835, four volunteer ranger companies arrived at the fort to join with a fifth company. Captain Robert M. Coleman, who had strongly advocated creation of a tax-funded ranger force to protect settlers, led the men. The rangers bought supplies from the Parkers and, after reorganizing, left the fort in August. The rangers had a few Indian skirmishes, but the battalion was mustered out of service in mid-September.

Had rangers remained stationed at Fort Parker, what happened in the spring of 1836 might have been averted. On May 19, 1836, several hundred Comanche and Kiowa warriors attacked the fort. They killed five men, including family patriarch John Parker—father of Ranger proponent Daniel Parker. Five women and children were kidnapped, including little Cynthia Ann Parker. The others escaped.

The reconstructed fort is off Farm to Market Road 1245, on State Park Road 35, north of Groesbeck. Initially a state park, the fort is now managed by the city of Groesbeck.

A year to the day after the attack, former ranger James Parker led an armed group to the abandoned fort and buried five sets of remains. Now known as Fort Parker Memorial Park, a large monument marks the mass grave.

Fredericksburg, Texas

Courtesy Texas Rangers Heritage Center

From Waco to San Antonio

For an overview of Ranger history, visit Waco’s Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum (100 Texas Ranger Trail). First known as Fort Fisher (a short-lived ranger post established there in 1837), the museum opened in 1968 and has expanded since then. Sited on 32 acres on the south bank of the Brazos near downtown, the complex was later rebranded the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum.

In addition to exhibits telling the Ranger story, two works of Ranger-related public art stand outside the museum: A bronze of noted Ranger and surveyor George B. Erath and a larger-than-life bronze of an early-day horseback Ranger bearing the Texas flag. Inside is a third piece, a life-size Ranger statue, Old Ranger.

Since its founding in 1839 as the capital of the Republic of Texas, Austin has been the headquarters of the Rangers.

Construction began in 1853 on a limestone statehouse to replace the original frame capitol, which was in poor repair. There, in 1874, legislators created the Frontier Battalion of Rangers. For the first time in Texas history, the Rangers were vested with law enforcement authority.

The Rangers were led by Major John B. Jones, a former Confederate officer who furthered the force’s reputation as effective Indian fighters and prairie peace officers. Jones died in July 1881 and is buried in Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery (1601 Navasota St.)

In November 1881, fire gutted the 28-year-old capitol, and Ranger brass officed in a temporary statehouse until completion of the present red granite capitol in 1887. The Ranger headquarters remained there until the creation of the Texas Department of Public Safety in 1935, when the agency relocated to Camp Mabry on Austin’s west side. The DPS remained headquartered at Camp Mabry (35th and MoPac Blvd.) until a new complex opened in North Austin in 1953. The Texas Military Museum on post explores the long connection between the state’s military and the Rangers.

The Bullock Texas State History Museum (1800 Congress Ave.) has three floors of permanent and changing exhibits. The museum’s website TheStoryofTexas.com includes a history of the Rangers.

The Texas State Cemetery (909 Navasota St.), final resting place of 30 Rangers and hundreds of other Lone Star notables, began with the death of one of those Rangers—Edward Burleson. In addition to his time as a Ranger or soldier, from 1841 to 1844 he’d served as vice president of the Republic of Texas. When he died in 1851, he was laid to rest on donated acreage in east Austin. That afforded Burleson one additional distinction—his was the first grave in a cemetery now considered the Arlington of Texas. In 1910, the remains of Stephen F. Austin were relocated to the cemetery.

In the heart of San Antonio, stands the most historic structure in Texas, if not the entire Southwest—the Alamo. The old Spanish mission, overrun by the Mexican army on March 6, 1836, is considered a shrine to liberty. While millions know the story, far fewer are aware that 32 Rangers died in the battle.

The Daughters of the Republic of Texas maintained the Alamo until 2015, when the state General Land Office assumed control. The state has improved site interpretation, undertaken needed restoration and recently opened the two-story, 24,000-square-foot Alamo Collections Center. That facility houses the extensive collection of Alamo artifacts assembled over the years by British rock star Phil Collins.

Just across from the Alamo, German immigrant William Menger opened a two-story hotel in 1859. The Alamo City’s finest hostelry throughout the 19th century, the Menger hosted presidents, generals, cattle kings, actors, famous writers and other notables. Many Rangers and former Rangers spent time at the hotel, including Captain John S. “Rip” (Rest in Peace) Ford. Much expanded, the Menger (204 Alamo Plaza) remains open today.

In 1881, Albert Friedrich opened the Buckhorn Saloon. Soon, accommodating customers short of funds, Friedrich offered to trade drinks for trophy steer horns and deer antlers. Before long, the saloon’s walls were covered with impressive mounts. The Buckhorn (318 E. Houston St.) remains in business. The Former Texas Rangers Association maintains an 8,000-square-foot Ranger museum there.

Gonzalez, Texas

Courtesy Gonzalez Memorial Museum

The South Texas Heritage Center (3801 Broadway St.) is a new addition to the nationally known Witte Museum The center focuses on the diverse cultures that shaped South Texas, from the Comanches to the Spanish, Mexicans, Germans and others, as well as cowboys and outlaws.

In the 1830s, Rangers periodically camped under a stand of trees along a spring-fed stream running through what is now downtown Seguin. The large trees, still standing (southeast corner, Gonzales and Travis Sts.), came to be called the Ranger Oaks.

Demonstrating they had business acumen as well as fighting skills, in 1838 Matthew “Old Paint” Caldwell and two other Rangers partnered to develop a town on land that included their former campsite. Thirty-three men—mostly Rangers—bought shares in the venture. The new town was named for Texas hero and former ranger Juan N. Seguin. The Seguin-Guadalupe County Heritage Museum (114 N. River St.) tells this historic community’s story.

Seguin’s grave lies beneath a flat granite tombstone at 789 S. Saunders St. A larger-than-life bronze statue depicting him astride a horse at the Battle of San Jacinto stands in the city’s Central Park bounded by Austin, Nolte, South River and Donegan Streets.

The best-known early day Ranger was Capt. Jack Hays, a Tennessee-born surveyor credited with establishing the Ranger reputation. In 1847, Hays got married in Seguin’s two-story Magnolia Hotel. One of the city’s oldest structures, the restored hostelry remains in business today.

Courtesy NYPL Digital Collection

When news reached Gonzales in 1836 that the Alamo had fallen, Gen. Sam Houston ordered the town burned. Escorted by the Texas army, townspeople—including the grieving widows and children of the 32 Rangers who’d volunteered to help defend the Alamo—fled eastward.

A monument to the men of the Gonzales Ranging Company stands outside the Gonzales Memorial Museum (414 Smith St.). A sculpted bronze plaque on the red granite cenotaph lists the names of those now known as “The Immortal 32.”

In 1897, aging former Texas Ranger John S. “Rip” Ford, as a newspaper editor, Indian fighter, soldier and politician, helped organize the Texas State Historical Association as well as the forerunner of today’s Former Texas Rangers Association.

San Antonio, Texas

Courtesy Witte Museum

Ranger Ring of Honor

More than a century later, the Former Texas Rangers Foundation (the nonprofit arm of the FTRA) began raising funds to build a heritage center dedicated to Ranger history and the many Rangers who died in the line of duty over the last 200 years.

In Fredericksburg, the first phase of the Texas Ranger Heritage Center (1618 Main St.) opened in 2015. Sitting on 12 acres adjacent to old Fort Martin Scott (the first frontier fort established in Texas), the complex includes a 50-foot limestone campanili; a Ranger Ring of Honor built around a 20-ton, five-point concrete Ranger badge replica 30 feet in diameter; an outdoor pavilion; an amphitheater; and a historical reenactment area. The heritage center’s second phase will include a museum with interactive displays and a Ranger archive.

A bronze statue of a Ranger leading a pack mule, originally placed in front of the old Pioneer Memorial Hall at San Antonio’s Witte Museum was refurbished by the FTRA and moved to the heritage center by the pavilion. Also standing near the pavilion is a bronze of an 1850s Ranger holding a Sharps rifle.

The Ranger Ring of Honor features plaques listing the names of all known Ranger line-of-duty deaths. Carved along the circumference of the badge are five Ranger-defining traits: Courage, Determination, Dedication, Respect and Integrity.

Longtime Texas writer Mike Cox, an elected member of the Texas Institute of Letters, has written 40 nonfiction books, including four volumes on Texas Ranger history.

Waco, Texas

Courtesy Texas Ranger Museum

Where History Meets the Highway

Museums

Bob Bullock State History Museum, Austin; The Alamo, San Antonio; Witte Museum, San Antonio; Frontier Times Museum, Bandera; Gonzalez Memorial Museum, Gonzalez; Texas Ranger Hall of Fame & Museum, Waco; Texas Ranger Heritage Center, Fredericksburg; Fayette County Heritage Museum and Archives, La Grange; San Felipe de Austin State Historic Site, San Felipe; Fort Parker Memorial Park, Groesbeck; Washington-on-the Brazos State Park, Washington; Seguin-Guadalupe County Heritage Museum, Seguin; National Ranching Heritage Center, Lubbock

Good Eats & Sleeps

Eats: 11th Street Bar & Grill, Bandera; Arkey Blue’s Silver Dollar Saloon, Bandera; Buckhorn Saloon, San Antonio; La Fonda On Main, San Antonio; Saltgrass Steakhouse, Waco; Lonesome Dove, Austin; Scholz Garten, Austin; Broken Spoke, Austin; Come and Take It Bar & Grill, Gonzalez; J. Cody’s Steakhouse & BBQ, College Station; Evie Mae’s BBQ, Wolfforth

Sleeps: The Menger Hotel, San Antonio; The Crockett, San Antonio; Emily Morgan Hotel, San Antonio; Pivovar, Waco; Kenmore Inn, Fredericksburg; The Driskill Hotel, Austin; Hotel Ella, Austin; Lone Star Court Hotel, Austin; The Dilworth Inn, Gonzalez; Belle Oaks Inn, Gonzalez; Cavalry Court, College Station; Cotton Court Hotel, Lubbock

Dude Ranches: Flying L Ranch Resort, Bandera; West 1077 Guest Ranch, Bandera; Dixie Dude Ranch, Bandera; Mayan Dude Ranch, Bandera; Rancho Cortez, Bandera; Wildcatter Ranch, Graham; Prude Ranch, Fort Davis

Lubbock, Texas

Courtesy NRHC

South Dakota

Discover adventure and cowboy history in the West River cattle country.

By Bill Markley

Spearfish, South Dakota

All Images Courtesy Chad Coppess Unless Otherswise Noted

West River South Dakota is cattle country. The Missouri River bisects the state from north to south, the eastern portion is called East River, and the western, the West River. Ancient glaciers forced the Missouri south along their western edges while West River’s streams and rivers, untouched by glaciers, continued cutting through the prairie from west to east. The Black Hills rise from the prairie to the west, while to the south, badlands stretch from west to east.

Rolling prairie, rich in grama and wheat grass, supported herds of bison, pronghorn, mule deer and elk. Cheyenne and Lakota tribes inhabited the land, and, after acquiring horses, metal spearpoints and arrowheads as well as firearms, they flourished.

The cattle industry got a late start in West River. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty established the Great Sioux Reservation which included most of West River. In 1877, the federal government removed from the reservation, the Black Hills and a 50-mile stretch of land along Dakota Territory’s western border. By 1886, professional hunters had decimated the West River bison herds. In 1889, the federal government diminished, then broke up, the Great Sioux Reservation into five smaller reservations, as Dakota Territory became the states of North and South Dakota. Most of West River became public domain—open range.

Through its treaty with the Lakota tribes, the federal government promised to provide them beef. Herders drove cattle from the east to the Lakota agencies, Standing Rock and Cheyenne River along the Missouri River, and after agencies were established at Rosebud and Pine Ridge, and along South Dakota’s southern border, Nebraska and Texas cattlemen drove herds to those agencies.

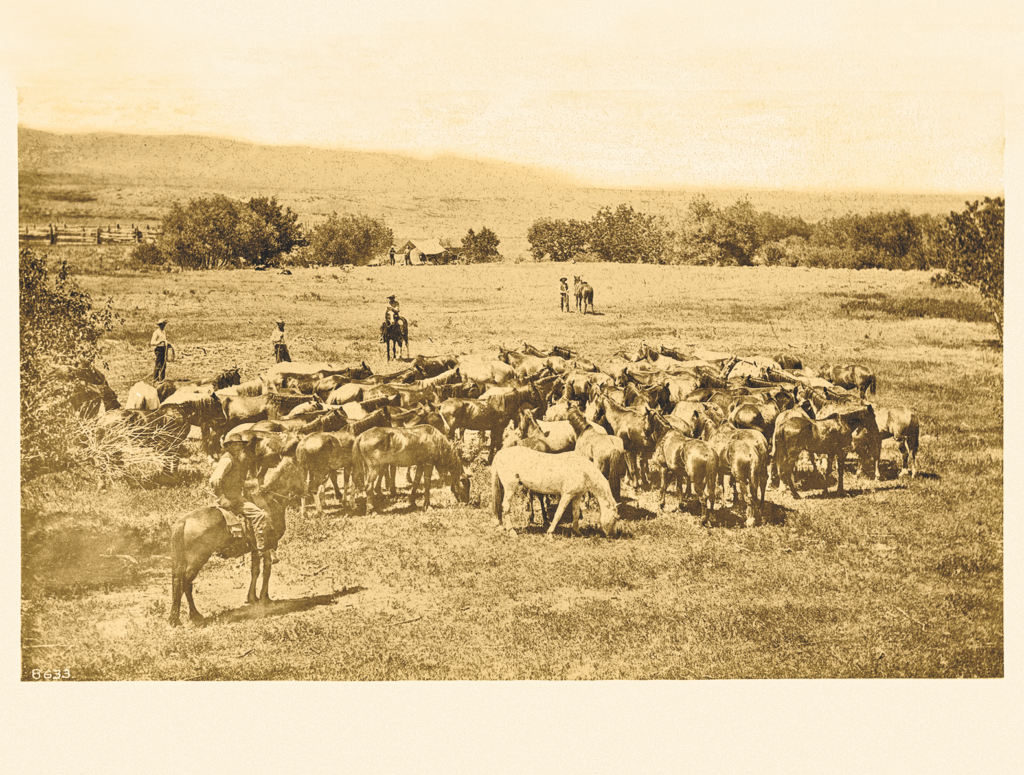

By 1878, West River cattle herds were thriving on the open range in the Belle Fourche area north of the Black Hills. The government had not opened the range for homesteading, so anyone could use it. In 1880, cattlemen formed the Black Hills Livestock Association, and by the winter of 1881-82, the 60 members of the association had an estimated 264,000 head of cattle. At first, most of the animals were Texas longhorns, later replaced by Herefords and Shorthorns; and many cowboys were from Texas.

Deadwood, South Dakota

Cattle outfits increased and expanded throughout the open range. There were no fences, and cattle tended to drift, especially during the winter. The cattlemen needed to recover their cattle, brand the calves and castrate the males. The livestock associations organized roundups in the spring and fall. The range was divided into districts. A cattleman was designated as district foreman, and each outfit sent a cowboy, called a rep, to take charge of any cattle belonging to the outfit. The reps worked together cooperatively under the direction of the foreman. They rode over a wide area, bringing back all cattle they found to a central location where they separated the animals into the owners’ herds. Calves were branded with the brands their mothers carried, and male calves were castrated. The cowboys then herded the cattle back to their home ranges. Fall roundups were held to separate out animals destined to be trailed to shipping locations.

Working cattle could be dangerous business. The cowboys needed to be alert for whatever nature might throw their way. George Gunn recalled a 1902 spring roundup where they were trailing a herd of 1,000 head along a ridge north of the White River. George wrote:

“…Ray Kehiler and I stayed behind [the herd] to haze up the drags or stragglers.

“All of a sudden, like a bolt out of the blue, we were struck from the NW with one of the worst wind, hail and lighting storms ever known in that part of the country. As the herd turned tail to flee from the storm, naturally Ray and I were in the thick of the rushing cattle rapidly making down the slope. When our mounts turned with heads down in the storm, our single rig saddles flew up behind, and we were unloaded out front.”

Ray’s horse ran off, but George was able to catch his. “When the storm hit, the four horses [pulling the mess wagon] jackknifed and the wagon rolled to the bottom of the canyon, scattering all contents along the way. Fortunately, no one in our outfit was hurt; several were left hatless and horseless. We tried to make a temporary camp and spent the rest of the dark night in our wet beds.”

In the early 1900s, railroads were built across West River, bringing homesteaders and ending the open range. Many homesteaders couldn’t make a go of it and left. Land was consolidated into larger holdings, so today there are cattle ranches, large and small. You can still find vistas of vast grasslands as the old-time cowboys would have seen.

Here are some suggestions for your West River tour.

Belle Fourche, South Dakota

Mobridge

The railroads established shipping points along the Missouri River. Cowboys drove West River cattle to the river ,where they were either ferried or swam across and then loaded onto eastbound trains. Located on the Missouri’s east bank, Mobridge was one of these destinations. The town’s name was a contraction of “Missouri River Bridge,” future site of the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway bridge. The completion of the bridge in March 1908 doomed Evarts, LeBeau and other downriver shipping points. One of Mobridge’s major events is the Sitting Bull Stampede Rodeo held every Fourth of July along with a parade and carnival.

Fort Pierre