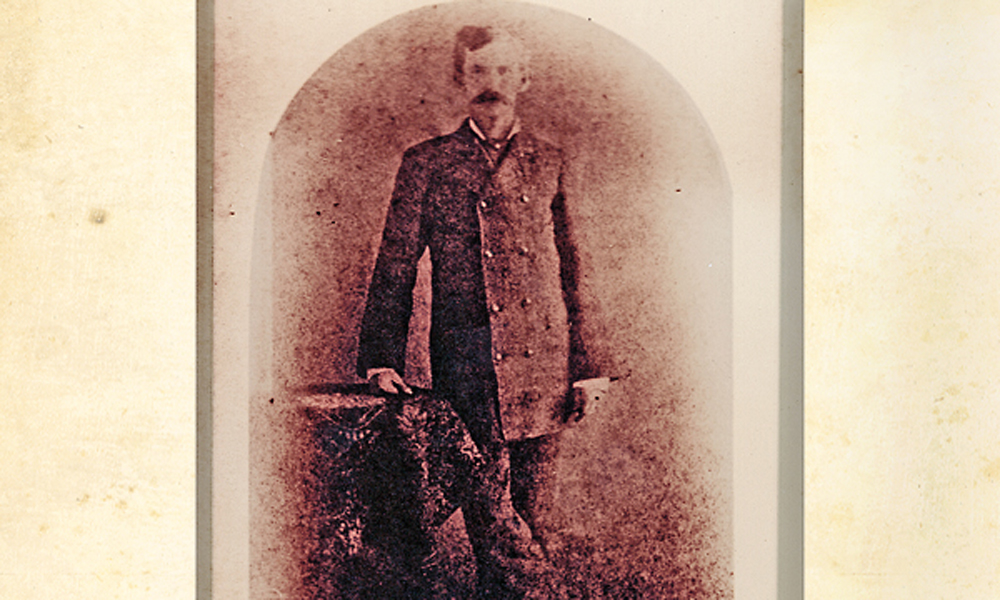

– Courtesy Dr. Robert J. Chandler –

Everyone knows his name, and everyone thinks they know his story. He’s Levi Strauss, the man who made the first blue jeans possible. But he’s also a figure of grand myth because the company he founded lost its historical records in the 1906 earthquake and fire in San Francisco, California. The real story was left in the ashes, but after spending 24 years as the company’s historian, I can right the historical record.

he week of December 10, 1894, was drizzly and cold in Benson, Arizona Territory. When the Southern Pacific shrieked into town, the passengers who stepped off the train were bundled up against the chill. Two of them were substantial, bearded men who walked directly into the lobby of the Grand Central Hotel. There, they signed the register: Adolph Sutro and Levi Strauss.

The clerk, no doubt pleased to have such distinguished men as guests, gave them first-class rooms, reasonable rates and the best of meals, just as the Grand Central advertised. The clerk and the hotel’s other guests thought they knew the identities of these illustrious visitors. But they were wrong.

The two gentlemen were impostors.

The real-life Sutro and Strauss were in San Francisco, California, that week, attending to their personal business.

Sutro, a Comstock Lode icon who invested his mining tunnel fortune into real estate, had just been elected mayor of the city and was preparing for the upcoming visit of Gen. William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army. Strauss, the president of Levi Strauss & Co., was a merchant, philanthropist and the man behind the popular copper-riveted denim “Two Horse” work pants. He was in court telling Judge JCB Hebbard why he couldn’t serve on the grand jury that term.

Whoever those men in Benson were, the faux Sutro and Strauss had themselves a good time, playing off the recognition of celebrities many thought they knew well.

– All images Courtesy Levi Strauss & Co. Archives unless otherwise noted –

A Figure of Grand Myth

For decades, the Levi Strauss & Co.’s story about Strauss, the founding of the company and the invention of blue jeans went like this: Strauss was born in Bavaria, Germany, in 1829, came to America and worked with his brothers in New York and Kentucky, then took a clipper ship to San Francisco, California, in 1850. There, he noticed that miners’ pants kept ripping, so he made a pair out of some tent canvas that he’d brought with him from New York. Later, he worked with a tailor in Reno, Nevada, to put rivets in the trousers and, at some point, dyed them indigo blue.

It’s a fun story, but it’s pure fabrication. Here’s how it really happened.

Bavarian-born Strauss emigrated with his mother and sisters to New York in 1848. His two older brothers were already there, and he worked in their wholesale dry goods business.

In 1853, Strauss took the Panama route to San Francisco to open up a West Coast branch of the family business, distributing the fine dry goods that his brothers shipped to him. His customers were general stores and men’s haberdasheries, and they served the small villages and growing cities of the frontier West.

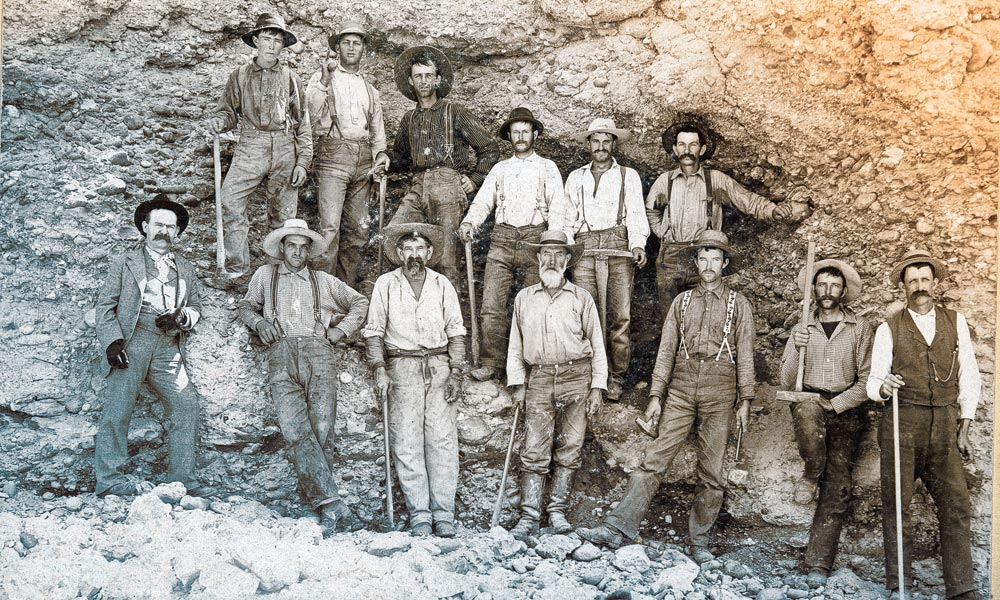

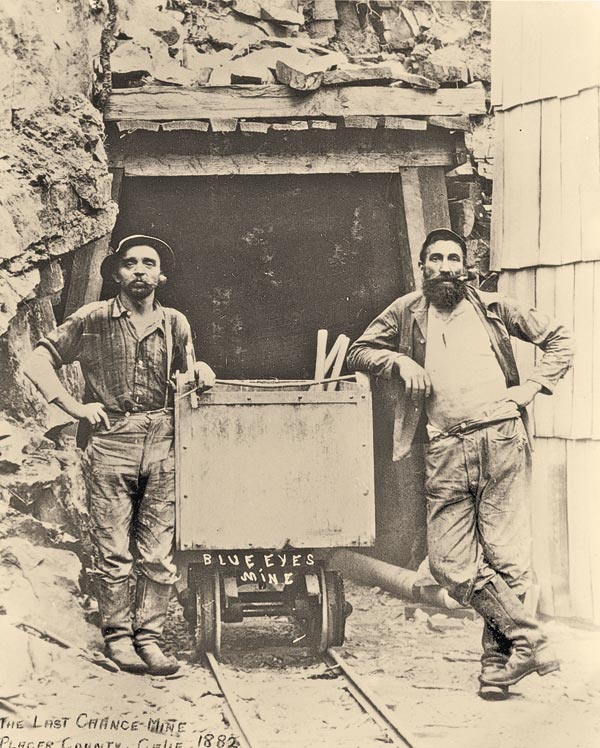

In 1871, a Russian immigrant named Jacob Davis, living in Reno, Nevada, started making work pants out of cotton duck and denim material, reinforcing the stress points with metal rivets. He wanted to patent this innovation, but needed a business partner. He turned to his fabric supplier, Strauss, and the two men received U.S. patent #139,121 on May 20, 1873. Within weeks, Levi Strauss & Co. began to manufacture and sell copper-riveted blue denim “waist overalls.” These two immigrants had invented the most American piece of clothing: blue jeans.

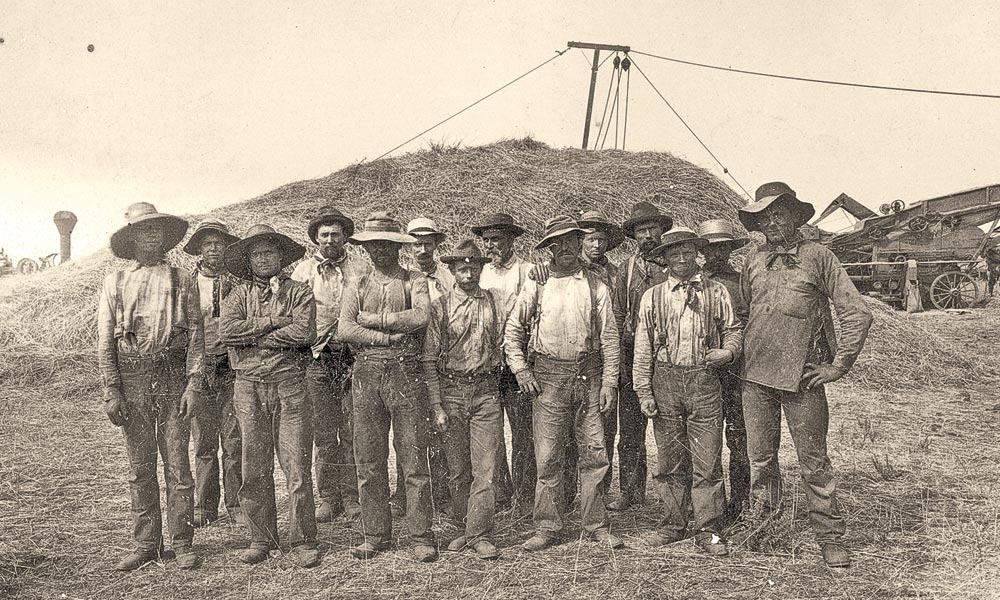

Strauss had his finger on the pulse of so much that we associate with the West, starting with the riveted pants. He knew that the Western states were filled with workingmen who labored as ranchers, lumberjacks, railroaders, teamsters, cowboys and miners. Those tough trousers were just what the tailor ordered.

But Strauss’s interests ranged farther, and his fame brought influence and, sometimes, danger.

Blow His Head Off

Take the case of Antonio Gagliardo. He was a failed store owner from Calaveras County, California. After declaring bankruptcy in 1885, he took off for Los Angeles. Recalling his former dry goods supplier, the wealthy and well-known Strauss, Gagliardo mailed Strauss a request to find him a store clerking job. Strauss sent him $50 and a kind note, but instead of being grateful, Gagliardo exploded with rage.

He wrote Strauss again and told him he had 10 days to get him a job or he would “blow his head off.”

Strauss had friends in San Francisco who knew Gagliardo, and they advised him to call the police, but Strauss said the poor man was simply “overexcited by his troubles.”

When Gagliardo showed up in San Francisco, though, Strauss finally paid attention and alerted the chief of police, who had the man arrested and tossed in jail. The case never came to trial because Strauss refused to prosecute. Why?

Gagliardo “promised to refrain from carrying his sanguinary promises into execution.” He kept his promise.

Infamous Customers

Some of Strauss’s customers were famous, and even infamous.

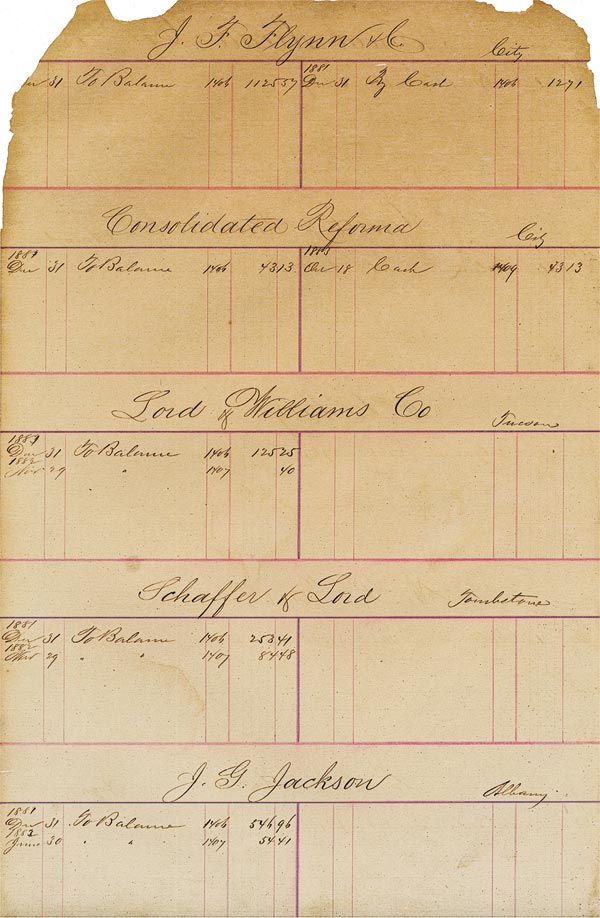

Shaffer & Lord, of Tombstone, Arizona Territory, sold Strauss’s riveted clothing and dry goods for many years; who knows how many customers were perusing their shelves as the shots from the O.K. Corral rang out nearby on that October day in 1881?

Joseph Goldwater bought dry goods from the firm in San Francisco and then took off for the “land of the rattlesnake and the tarantula” without paying, turning the goods over to a partner in Yuma named Isaac Lyons. Hearing that the law was on their trail, Goldwater and Lyons barricaded themselves into a store, armed with shotguns. When the U.S. marshal showed up, though, they quietly surrendered.

Whoever his customers were, Strauss had a strong pulse on his business. Transportation was key to commercial success for his California merchants, so he was especially interested in improvements in shipping. When he could, he had a hand in these improvements. In 1895, he gave $25,000 to help thwart the “Octopus”—the Southern Pacific Railroad, which had a stranglehold on Western freight rates. Strauss, sugar magnate Claus Spreckels and others founded the San Francisco and San Joaquin Valley Railway, which, for a time, gave shippers, large and small, an alternative to the Southern Pacific, and it was later sold to the Santa Fe Railroad.

– Courtesy Dr. Robert J. Chandler –

Not So Serious?

Strauss was serious about commerce, and looking at his stern face in his surviving photos, you would think he was serious about everything. But the historical record offers hints that he also had a warm and even hilarious side.

In 1888, he let one of his customers use his books to check the credit ratings of mutual store accounts. The customer, dry goods merchant Henry Lash, sometimes sent his 18-year-old son Samuel in his stead. Samuel was always in awe of the famous Strauss and deeply impressed that the great man insisted on being called Levi and not Mr. Strauss. As Samuel later said, “I still remember Levi Strauss as one of the finest, kindest and friendliest gentlemen I’ve ever met.”

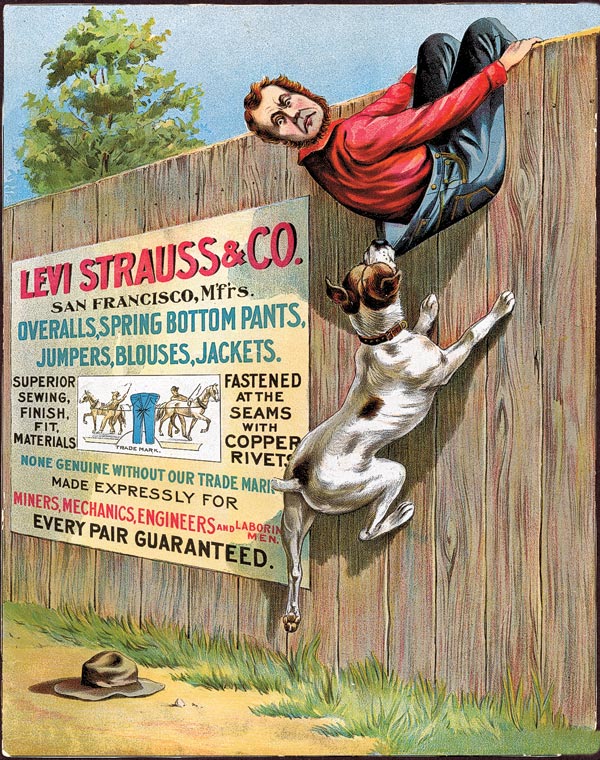

Then there’s hilarious: in the late 1880s, the company began to print colorful flyers about the riveted clothing, with illustrations demonstrating the strength of the pants. In 1897, the firm put a new flyer into circulation. It featured a man in a red shirt and riveted denim trousers, hanging onto a fence by his hands and knees, as a large dog grips the man’s pants with its jaws. On the fence is a large handbill advertising the Levi Strauss & Co. patent riveted clothing. At the bottom of the flyer are the words, “Never Rip, Never Tear, I Wish They Did Now.”

That’s funny enough, but here’s the best part: the man on the fence is Strauss. This says a lot about the founder’s personality and his belief in the power of advertising. It’s hard to imagine any of his contemporaries allowing themselves to be a figure of fun in the name of sales.

Toughie with a Soft Spot

When Strauss died in 1902, newspaper headlines called him a merchant and philanthropist. Yes, he had built a multi-million dollar business, but he was also a man of deep compassion. He created scholarships at the University of California in Berkeley that are still in place today. He gave thousands of dollars to disaster relief all over the world. And he left equal amounts in his will to San Francisco charities aimed at children and the elderly.

Tributes to his character filled newspaper columns in the days after his death, and stories were shared at his funeral, all laudatory and heartfelt. But for my money, the comment made years later by one of the women who worked at his blue jeans factory sums him up best.

“He was tough, but a fine fellow.”

A member of Western Writers of America, Lynn Downey is the historian emeritus for Levi Strauss & Co. and author of Levi Strauss: The Man Who Gave Blue Jeans to the World, published by University of Massachusetts Press.