– Courtesy Library of Congress –

When Joseph W. Evans passed away suddenly on May 28, 1902, at his home in Phoenix, Arizona Territory lost one of its most successful businessmen and a distinguished citizen, reported the Arizona Republican newspaper, which printed a lengthy and glowing eulogy the day after his passing.

– Courtesy Peter Brand –

During his lifetime, Evans had worked as a successful stagecoach agent, a Wells Fargo operative and a deputy U.S. marshal. He rode in countless posses, made numerous arrests and knew famous lawmen who included Wyatt Earp and Bob Paul. His eulogy focused on his life after his career in law enforcement, but it left out one fact that made his achievements even more noteworthy—for the majority of his time in Arizona, he had the use of only one arm, courtesy of a gunfight that took place in Prescott in 1875.

Upstaged in Arizona

Born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, on July 4, 1851, Evans was raised by his mother after the premature death of his father in 1854. Federal census records for 1860 show that the family was comparatively well-off in Fayetteville, prior to the Civil War, with real estate holdings estimated at $4,000. By the 1870 census, however, the family’s asset worth had halved. Evans was enumerated on this census as an 18 year old clerk who resided with his mother, sister and grandmother in Cross Creek.

Evans left North Carolina sometime after the 1870 census and, along with many other like-minded young men, headed west. By 1872, he had arrived in Phoenix, Arizona Territory.

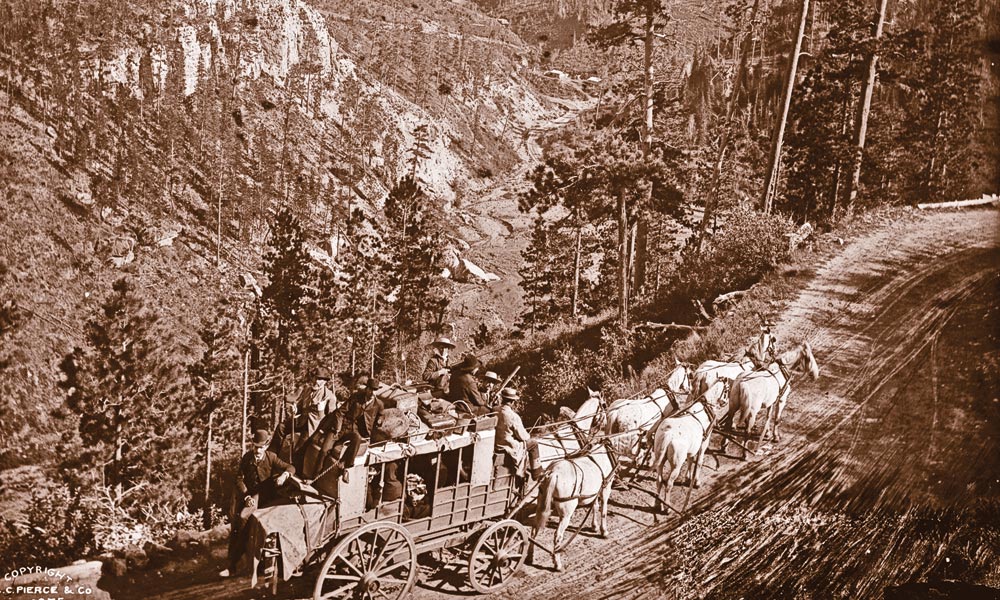

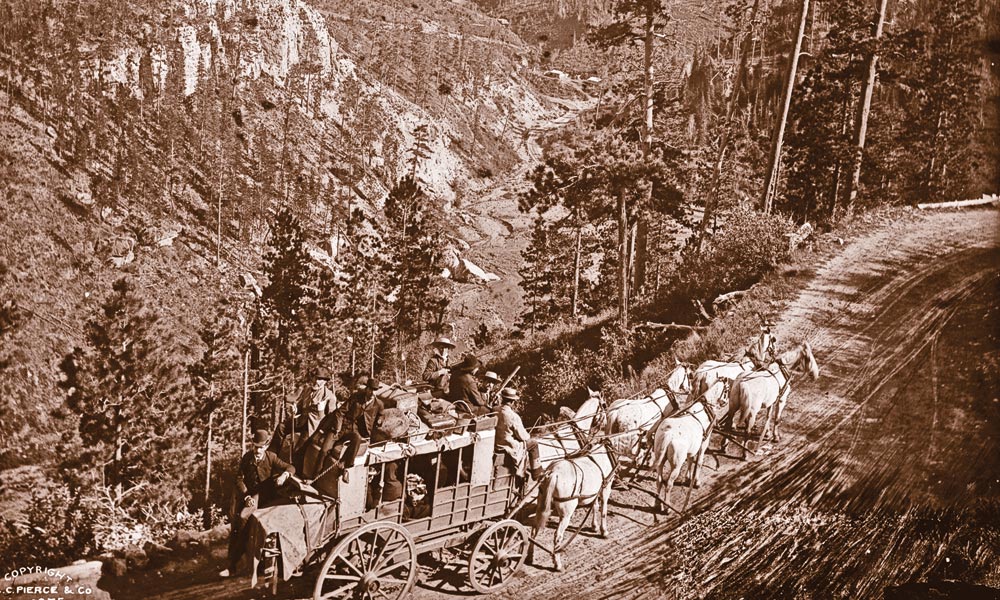

On December 26, 1873, the Weekly Arizona Miner newspaper announced that Evans was in Prescott to look after James Grant’s stage business, and he was soon appointed as the managing agent there. Grant owned one of the major transport companies in the region, Arizona Stage Lines. The seasoned businessman and stage line proprietor had secured the government contract to carry the mail on the three most important and lucrative routes at the time—including California’s rich San Bernardino-to-Prescott run.

The growing business soon became known as the California and Arizona Stage Company. Evans proved to be a good agent, and the local press commended the company’s excellent mail delivery, although Grant also received criticism for using buckboards to transport passengers, rather than the more costly, yet relatively comfortable, Concord stagecoaches.

Two of Evans’s best drivers were William Reid, who rode the Mohave route, and James Carroll, who drove the Prescott-to Wickenburg-run. In his early 30s, the experienced Carroll had previously worked for stage companies in Colorado. Local press had praised both Reid and Carroll for their ability to drive on dangerous waterlogged roads and keep their stagecoaches upright and their passengers safe. As good as he was with a six-horse team, Carroll apparently clashed with Evans over matters that may have related to Carroll’s heavy drinking. Evans and the Prescott postmaster, James Giles, wanted Carroll transferred away from Prescott, and the two men intended to strongly recommend to Grant that he do so.

They never got their chance.

On the evening of February 12, 1875, Reid was hitching a team to a buckboard for the regular mail run from Prescott to Wickenburg. Reid was assisting Carroll, who was too intoxicated to round up the horses that were scattered around the corral. When Evans came out of the stage office and saw the situation, he confronted Carroll, telling him that he was too drunk to drive the buckboard. Evans declared that he would drive the buckboard to Wickenburg himself and went back into the office to dress for the night journey.

But after Reid finished hitching the team to the buckboard, Carroll foolishly mounted the vehicle and took the reins. Evans emerged from the office visibly annoyed that his directive had been ignored by the drunken driver.

“If you don’t get off, I’ll put you off!” Evans told Carroll, to which Carroll sarcastically replied, “You will put me off, will you?” Evans declared, “I will if you don’t get off!”

No sooner had he uttered the last word, when Carroll pulled a gun and opened fire on Evans, shooting at least three times. One bullet struck Evans in the left forearm, about three inches below the elbow. Evans managed to draw his gun and return fire before he fell backwards into the office doorway for cover.

As gunshots exploded around them, the horses reared and the two “wheelers” fell. Reid tried to hold onto the two lead horses. As the buckboard jerked, Carroll, who had been grazed on the side of the head by one of Evans’s bullets, fell between the horses.

Hearing Carroll’s call for a rescue, Reid gathered Carroll into his arms and dragged him clear of the horses. Having just barely escaped a desperate situation, Carroll noticed another one on its way—he saw the wounded Evans emerge from the office doorway, so Carroll raised his gun and opened fire. Evans did likewise, blazing away, and one of his shots drilled Carroll in the head as he was still in Reid’s arms. With blood gushing from his second head wound, Carroll collapsed on Reid, who had been grazed in the thumb from a shot fired by one of the shooters.

Reid moved Carroll to the nearby Post Office, where onlookers attended to him as someone sent for medical help. When Dr. George Kendall came on the scene, he found two gunshot wounds to Carroll’s head—one of which he deemed fatal. The doctor dressed the wounds as best he could and went to seek further assistance from a colleague. He returned with Dr. James McCandless, who confirmed the grim diagnosis. Carroll died four hours later. The owner of the stage line, Grant, expressed his deep regret at what he called the “unfortunate shooting affray.”

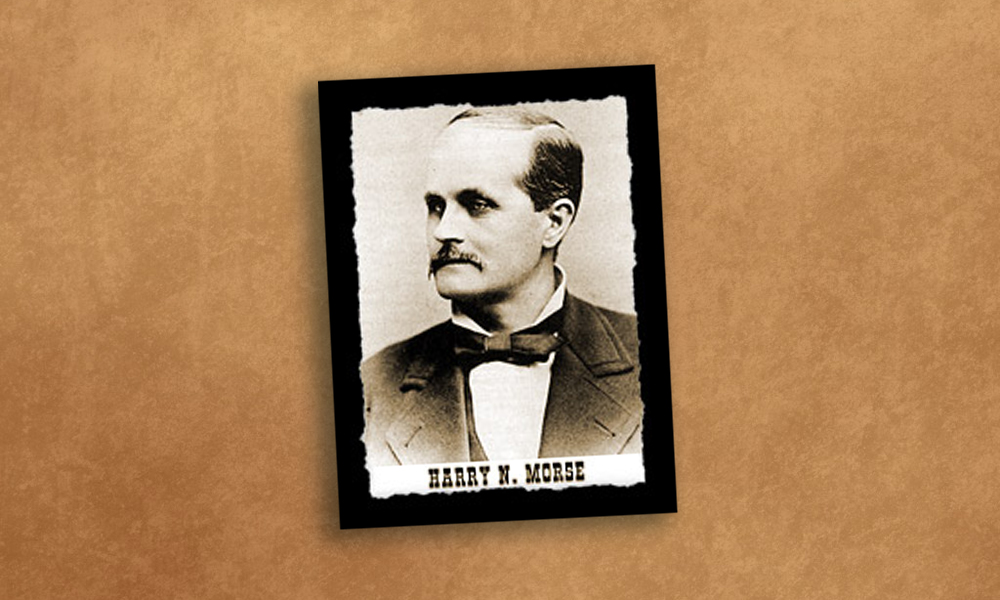

– Photo True West Archives –

Risking Life and Limb

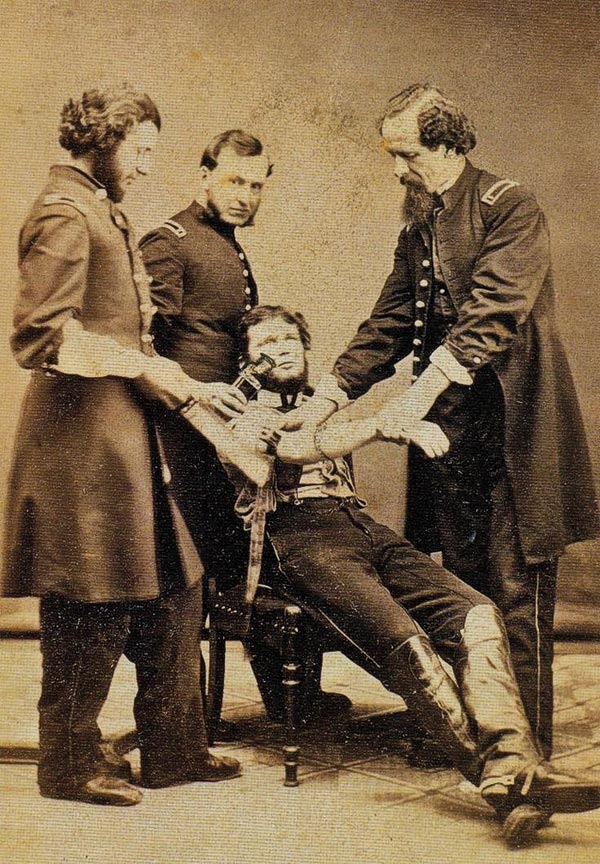

After Evans was placed under arrest for killing Carroll, Dr. McCandless treated his patient’s wounded left arm. The bullet had passed between the bones of the forearm and he thought, at first, that the wound was not serious.

Within two weeks of the shooting, however, Evans was in trouble. Infection had taken over, and his left arm, left shoulder and breast were inflamed. The circulation in his damaged left arm was failing and gangrene had set in below the elbow. A U.S. Army surgeon from the nearby post, Dr. Henry Lippincott, was called in to examine Evans. His prognosis was bad—the arm needed to be amputated, just below the left elbow, or Evans would die. The operation on February 27 was a success, with Dr. Lippincott assisted by Dr. McCandless and Dr. Kendall administering the anesthetic, The Weekly Arizona Miner reported.

The operation saved Evans’s life, but he was not out of danger yet. On the morning of March 12, the wound hemorrhaged badly and Evans lost a considerable amount of blood, leaving him in a weakened condition. His doctors stitched the wound again to stop the blood flow. A week later, The Weekly Arizona Miner reported that the patient had “turned the corner” and was on the way to recovery.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

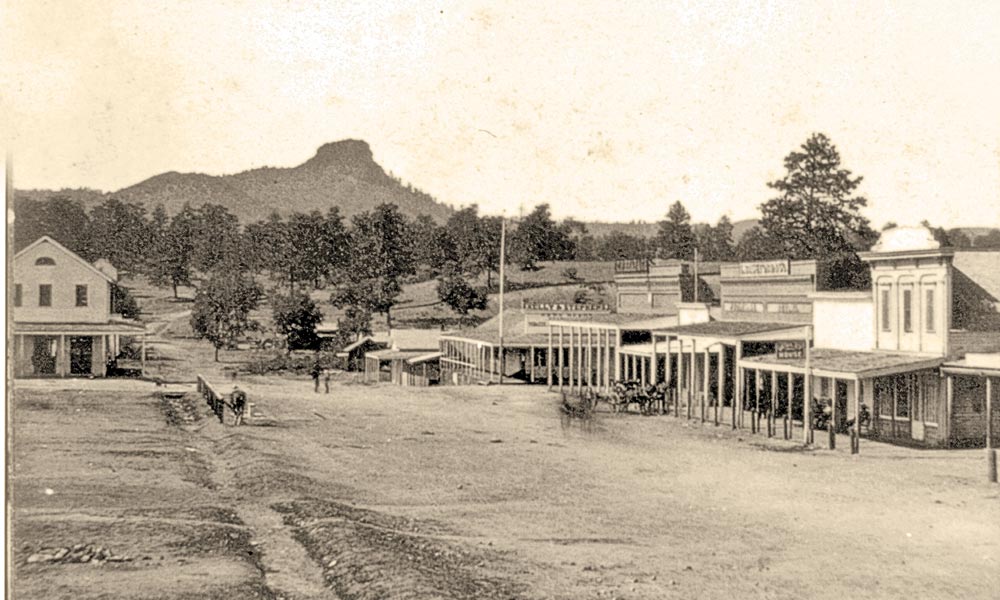

By the middle of April 1875, Evans was up and walking about town. He was well enough to appear before Justice Harley H. Carter on a charge of murder, was duly indicted and then released on a $500 bond to await his trial.

When Evans was arraigned in early May, he pleaded “Not Guilty.” The trial began on May 20 in the district court in Prescott. On the morning of May 21, the district attorney admitted that the evidence proved insufficient to prosecute Evans, and the judge ordered the jury to find in favor of the defendant. On the same day that Evans was released, his boss, Grant, suffered a suspected heart attack while out scouting a better stage route into San Bernardino. He died before he knew his agent had been acquitted.

A Short-Lived Yet Fearless Life

Evans continued to work for the California and Arizona Stage Company until 1877, when he took up a position as a Wells Fargo operative. The next year, Evans also became a deputy U.S. marshal. His ability to make arrests and handle the rigorous duties of the job in the field, with only one arm, gained him many admirers and earned him a reputation as a fearless and dogged lawman.

One 1878 stagecoach robbery, in particular, highlights his arduous work. After three men robbed a stage 20 miles west of Maricopa Wells on September 2, Evans received a tip that one of the suspects was in Rio Mimbres, New Mexico. Not finding his man, he followed clues to Silver City and from there he rode to Fort Cummings and then toward Clifton, Arizona. At a point 15 miles above Camp Thomas on the Gila River, Evans came upon a herd of cattle and found his man, who was working for the trail boss under an alias. The suspect, James Rhodes, was convicted and sentenced to nine-and-a-half years in Yuma Territorial Prison.

Evans enforced the law until the mid-1880s, when he moved to Phoenix and entered the business world. Evans created a profitable real estate and loan company, became the president of the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce and the president of the Phoenix Board of Trade.

When he died in 1902, aged only 51, Evans was lauded as one of the most successful and progressive businessmen in Phoenix’s short history. He should also be remembered as a man who triumphed over physical adversity and became one of Arizona Territory’s most determined and dutiful lawmen.

Peter Brand is a writer and researcher of the American West, who is based in Sydney, Australia. He has written books on the life of Texas Jack Vermillion and on conman Perry Mallon. See TombstoneVendetta.com for more details.