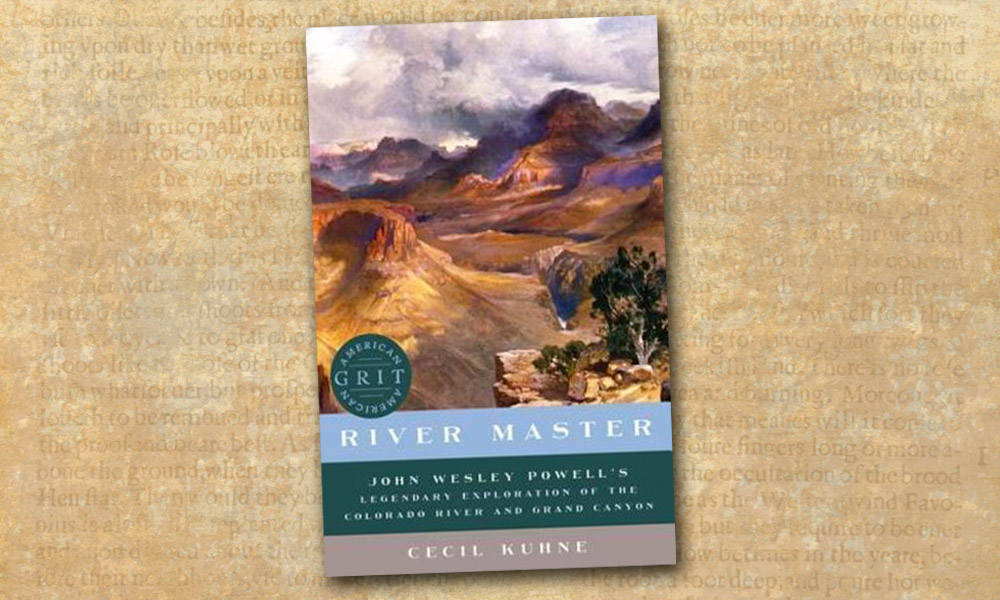

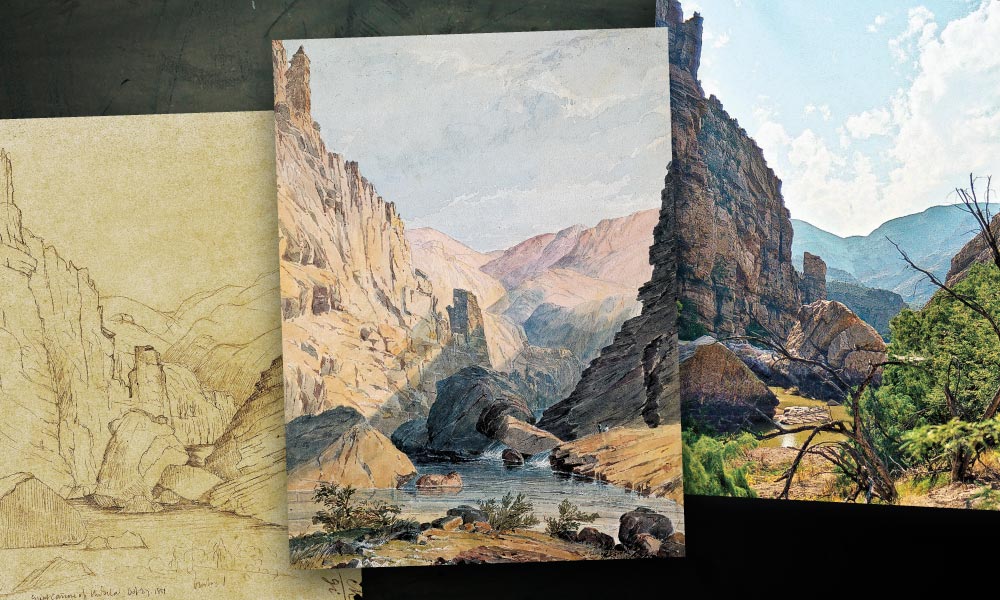

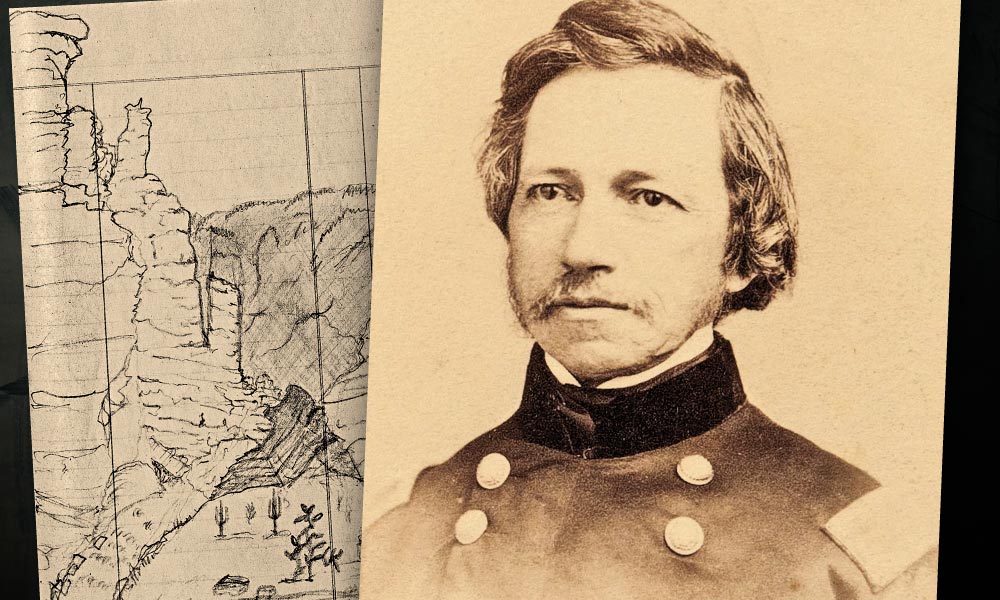

The dramatic Seth Eastman watercolor of a canyon on the Gila River of Arizona, circa 1853, is familiar to many students of Western exploration in general and of the first United States and Mexico Boundary Survey, 1849-1853, in particular. It is titled simply, Great Canyon Rio Gila, with little hint of its precise location.

On October 26, 1851, two days after he mentions passing the San Francisco River, boundary surveyor Amiel Whipple records in his diary a crude pencil sketch of the same scene. Based on this, the presumed location of the sketch and watercolor was, until recently, assumed to be somewhere in the Gila Box wilderness, west of the mouth of the San Francisco River, about six miles south of Morenci, Arizona.

The San Francisco River empties into the Gila a scant 19 miles from the eastern edge of the State of Arizona. This reach of the Gila has been protected since 1990 within the Gila Box Riparian National Conservation Area. Vehicular access is permitted at only three camping areas, but kayak, raft and canoe floaters are allowed. Curiously, although scholars accepted the Gila Box as the location of the drawing, no one visited the site to make a modern photograph or record its exact position on the river.

THE SURVEY

After the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, the agreed-upon boundary between the United States and Mexico was the Gila River across most of modern Arizona. The U.S. appointed John Russell Bartlett, a New York book dealer from Providence, Rhode Island, and a gifted artist, commissioner for the official survey of the new boundary between the U.S. and Mexico. He accompanied the field crews for part of the journey, but much of his tenure was spent exploring Mexico and California—areas not related to his duties.

The Seth Eastman watercolor is somewhat puzzling because Eastman, a U.S. Army officer, was not with the survey crew during their work in the Southwest. To add to the mystery, Bartlett made a sketch of the scene that is almost identical to the watercolor, but Bartlett was never at the location either.

So, we are left with the mystery of who made the original detailed sketch at the scene. One theory is that the image was based on Whipple’s crude diary sketch, which was later formalized by Bartlett and then used as the basis for Eastman’s watercolor.

In 2002, Oklahoma historian Dr. David H. Miller sent me his typescript of Lt. Amiel Whipple’s diary and suggested that we try to find the location of the Eastman watercolor. This is a location of interest on the Gila River boundary survey because the canyon became impassable and the survey had to be interrupted here and picked up again downstream.

Upon examining Lt. Whipple’s diary, we found that the boundary surveyors did not travel through the Gila Box at all, but began the Gila River portion of their survey northwest of modern-day Safford, some 30 river miles west of the San Francisco River and Clifton/Morenci. We soon realized that the “San Francisco River” described by the surveyors in 1851 is not the present one near Clifton, but is instead the stream we know as the San Carlos River, about 24 miles southeast of Globe and seven miles east of Coolidge Dam.

Based on that determination, we expected the Eastman view to be somewhere downstream from Coolidge Dam. The next step was to find it.

THE SEARCH

On our first visit, we examined the first few miles below Coolidge Dam. Since we were in an SUV, we could investigate only the first four miles of the canyon. We hiked a little beyond that, but the scene we sought was not there, and the river flow made further exploration difficult.

Our Apache companion advised us to return in the fall, when the water flow from Coolidge Dam is shut off for maintenance. During that time, we would be able to walk down a relatively dry river bed downstream of the dam.

For our second trip, in November 2003, we were accompanied by Dr. Jerry E. Mueller, a geomorphologist and authority on Bartlett, and Dr. Harry Hewitt, a history professor. We drove down the canyon as far as we could and then continued downstream on foot. I carried with me a print of the Great Canyon watercolor and a copy of Whipple’s diary so we could compare the historical account with the modern canyon scenery.

After following the serpentine course of the river canyon on foot for about two-and-a-half miles, we began to see the tops of the canyon walls ahead that resembled the Eastman view. We were about 20 miles southeast of Globe, Arizona, in the heart of the Bureau of Land Management’s Needle’s Eye Wilderness Area. Finally, we turned an angle of the canyon, and the full scene came into view about a mile ahead. We had not expected this: when we saw the real scene, we discovered that Eastman’s watercolor was almost photographically accurate!

How could artworks by two men who had never been at the scene be so precise? Someone in the canyon that day made a careful, detailed sketch of the scene. Who was it? A notation in Whipple’s diary identifies the likely artist. Whipple wrote at the scene, “The sketch by Mr. Wheaton shows the present termination of the survey.”

THE IMAGE

Historians are confused about which sketch Lt. Whipple refers to, since a crude drawing of the same scene appears on the opposite page of his diary, and several other drawings, in a similar untrained style, are included in his diary, to illustrate the people and places he wrote about.

I believe that the sketch that Whipple refers to is a formal pencil sketch drawn by survey assistant Frank Wheaton to record the appearance of the place as part of the official survey. In fact, in the lower right corner of Whipple’s diary sketch, he shows a man sitting on a rock—perhaps Wheaton making his drawing.

The original of this field illustration has not been located, but a copy of it appears on the first page of one of Commissioner Bartlett’s sketchbooks. Bartlett noted on the drawing that it was a “sketch for Frank Wheaton.” It appears that Bartlett made a copy of the field drawing for its original creator, and for himself, before submitting it with the final survey report. A copy eventually came into the hands of painter Eastman, who used it to create his beautiful watercolor painting a couple of years later.

THE CAMERA

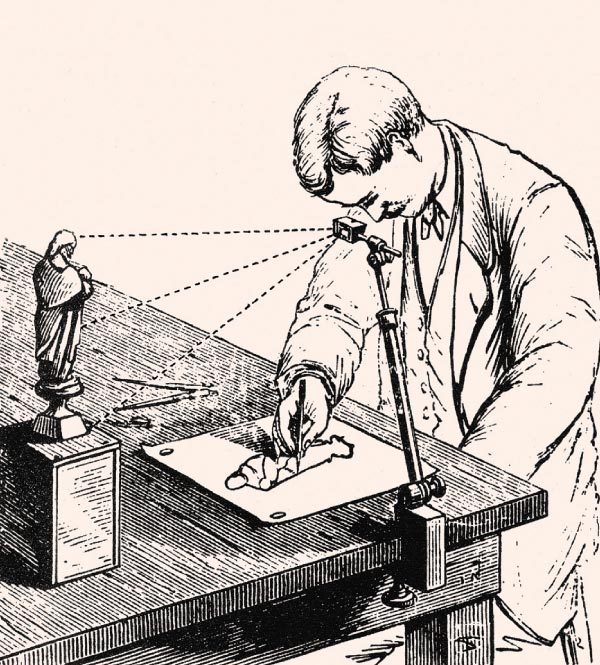

Wheaton, a civil engineer by trade, was one of Lt. Whipple’s assistants on the astronomical arm of the survey crew. How did Wheaton create such an accurate image? He probably used a camera of sorts.

This was not a photographic camera, which would have been difficult to transport and use in the wilderness in that day. Bartlett had procured a camera lucida as part of the equipment for the surveying expedition. This optical instrument would assist a person, with or without artistic talent, in making a faithful drawing of any scene.

The view in the sketch and watercolor looks westward between thousand-foot cliffs at the narrowest part of the Gila River Canyon, 8.5 river miles below Coolidge Dam. The boulder-choked canyon narrows to less than 100 feet wide here (Whipple reports it as 30 feet), making passage difficult to impossible by foot, horseback or even boat, a conclusion suggested by the shredded remains of a rubber raft on the rocks when we visited in 2003.

– Published in Scientific American Supplement, January 11, 1879 –

THE TRAILS

Since the surveyors could proceed no farther downstream, they took to the hills north of the river and followed a long detour through the Mescal Mountains, reaching the Gila again, a week later, at the mouth of Dripping Springs Wash. They were forced to take sightings from a distance to plot the approximate course of the river in the inaccessible portion.

Interestingly, Eastman’s watercolor shows the stream flowing toward the viewer, when, in reality, the river flows away from the viewer at the site. Eastman would not have known this since he had never been there. He must have added the flowing water for artistic effect.

Fur trapper James Ohio Pattie had visited this canyon in February 1826 and apparently took a similar detour through the mountains after finding the river blocked.

In 1846, just a few years before the boundary survey expedition, a small army under Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny arrived in the area. The guide, Kit Carson, led the men on a different detour, through the mountains, on their march of conquest to California. The soldiers did not travel to the Needle’s Eye; Carson instead chose an upstream detour, because he knew of the river blockage ahead, having trapped the river years earlier with Ewing Young.

Although several historic expeditions passed through and around the canyon, adventurers soon developed better routes through the mountains, leaving the remote chasm largely undeveloped and more or less forgotten. Consequently, the knowledge of the location of Eastman’s beautiful canyon landscape faded into obscurity.

– Sketch Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division, Amiel Weeks Whipple Collection; photo courtesy Heritage Auctions, December 12, 2014 –

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The impassable canyon played an important role in shaping the modern boundary of Arizona and the United States. At the conclusion of the Mexican-American War, in addition to the new international boundary along the Gila River, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided for the construction of a railroad within one marine league (about three miles) of either side of the Gila River. This railroad was planned as a way to provide all-season transportation to and from southern California, with minimal construction costs.

The Gila River survey and the accompanying canyon sketch proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that building the railroad in that location would be impossible. Proponents of a southern route for the transcontinental railroad then began a push to acquire more land south of the river, which eventually led to the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, adding more than 29,000 square miles to what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico.

Without the rugged mountains and canyons on the Gila River documented by the boundary surveyors, southern Arizona might still be a part of Sonora.

Cartographer Tom Jonas specializes in 19th-century trail research in Arizona and the Southwest, cartographic analysis and custom historical mapping.