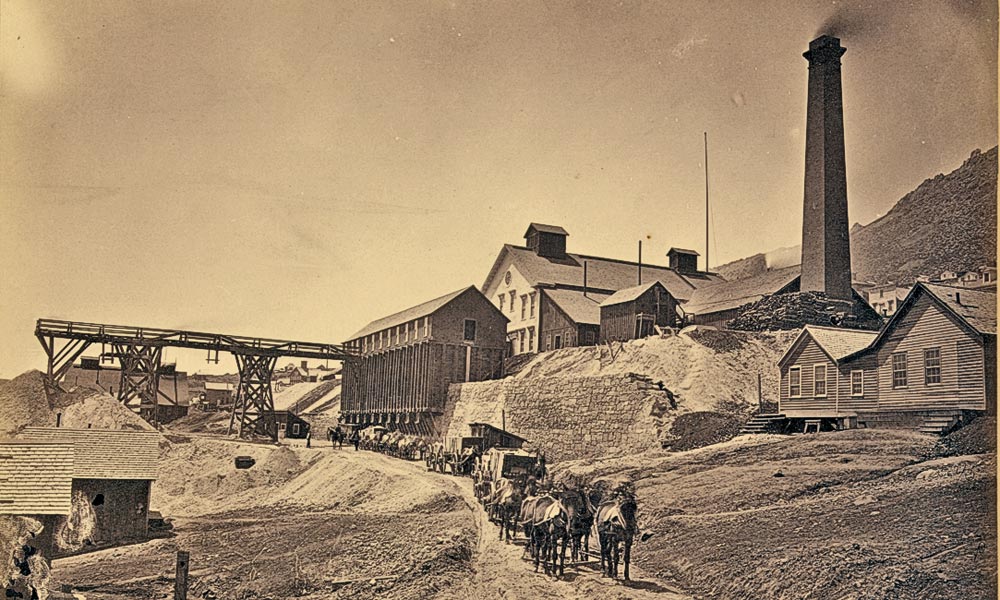

– Courtesy Comstock Foundation for History and Culture –

Talk about the mother lode.

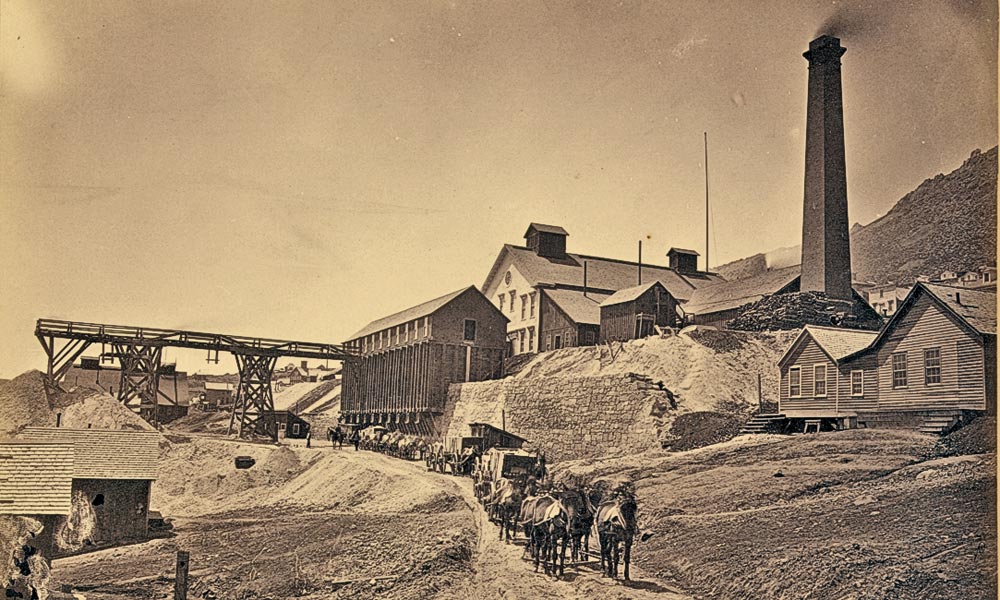

Imagine trying to preserve hundreds of projects in a 14,000-acre district—not only one of the nation’s largest historic landmarks, but one of its most important. Here, in these western mountains of Nevada, is where the “Comstock Lode” became America’s first major silver strike.

More than 100 mining companies dug these hills from 1859 to 1892, taking out more than $350 million in silver and gold. The lode made Virginia City the richest place on earth and gave America a string of mining towns unlike any it had ever seen—Gold Hill, Silver City, Dayton and the old town site of Sutro.

But that was then, and this is now, and now so much of that glittering history is falling to ruin or ready for a developer’s bulldozer.

Stopping that is the job of the Comstock Foundation for History and Culture, first organized in 2010 by Comstock Mining, which committed one percent of its bullion from the Lucerne Pit to preservation. The company turned to the community to form a private nonprofit that would use those funds to save the most endangered historic resources of the district—from legendary mines to churches to homes. But a drop in mining activity dried up those funds.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

The foundation’s Executive Director Pamela Abercrombie is not sitting back to wait for mining to return—this fast-talking walking history book is seeking grants and organizing fundraisers to keep projects going.

The foundation has already restored the Upper Yellow Jacket Hoist and Ore Chute in Gold Hill—standing above the tracks of the Virginia & Truckee Railroad and seen by tens of thousands annually.

Abercrombie notes the foundation had to move fast, because the chute risked “complete demise.” It took about $125,000.

A far bigger project—at least $4 million and counting—is the quest to save the Donovan Mill and transform it into an interpretive center and Silver City museum.

In these parts, no name is more important than Donovan, as in William Donovan Sr., who, in 1912, purchased a mill that dated to the 1860s. With his sons, especially the namesake, William Michael Donovan, the family operated the plant for 47 years—an unparalleled time span for early Nevada milling operations.

So far, the foundation has bought the mill and is raising money for its preservation and restoration. Abercrombie has secured several grants, including $15,000 from local miner Art Wilson, following in the footsteps of his father, who came here to mine the Comstock in the early 1900s.

“If I had a budget of $1 million, we would fund hundreds of projects,” Abercrombie says. “We promote history, and we have a rich history to promote.”

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.