In early 1897, Augustus Thomas was discouraged, despite being one of America’s finest playwrights. Thomas turned to a neighbor in New Rochelle, New York, for some ideas. That friend—famed artist Frederic Remington—pointed westward.

For years, Remington had been spinning tales of a visit to Arizona more than 10 years earlier, and Thomas saw potential in the artist’s remarkable stories. In March 1897, armed with letters of introduction from Remington, the writer headed west.

For the next few weeks, Thomas made the rounds, primarily of southeast Arizona. He visited Willcox and Camp Grant. He spent a week at the San Carlos Apache agency, learning about the tribe’s customs as well as those of the watchful soldiers.

But one man, one place, left the greatest impression on Thomas: Henry Hooker, the owner and king of the legendary Sierra Bonita Ranch. In his autobiography, The Print of My Remembrance, Thomas wrote a great deal about the “quiet little man” who had lived so many adventures (including hosting Wyatt Earp’s Vendetta Riders in 1881). Thomas was also charmed by Hooker’s daughter-in-law Forrestine, a beautiful young woman “who away out in the wilds played the piano with such delightful skill.”

Several years later, she made the first attempt at writing Earp’s biography. The adobe ranch house where she wrote became a fixture in Thomas’s next work.

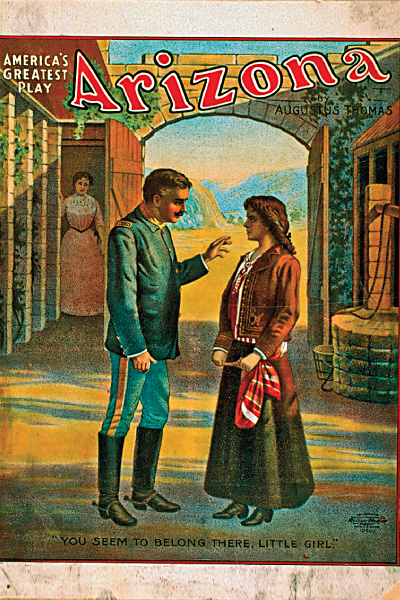

Thomas returned to New Rochelle, to put that next work on paper. Hooker became the lead character, a rancher called Henry Canby (a bit taller than the real man), and entire sections of dialogue were direct quotes from Hooker. The ranch changed names to Aravaipa, but was still located in southeast Arizona. And Forrestine became the heroine of the story, Bonita Canby. The story tells a tale of love between a young cavalryman and a rancher’s daughter, with subplots of treachery and deceit and adultery—a Victorian potboiler. Thomas gave his play the simplest of names, Arizona.

A little delay, called the Spanish-American War, put off the presentation of the play. The production finally premiered on June 12, 1899, at Harry L. Hamlin’s Grand Opera House. The audience loved it—applauding during two curtain calls after the first act, three after the second and five after the third in the four-act play. The New York Times reviewed, “In every respect it is stronger, in plot and treatment, than either of his best-remembered

other plays.”

The article mentioned another item special to the show: scenery designed by the master artist (and Thomas’s good friend) Remington.

Arizona hit Broadway in 1913. That same year, a silent film adaptation, directed by the author, was featured on the silver screen (two more versions made the movies over the next 18 years). Arizona became Thomas’s best-known work—although it was virtually forgotten by the mid-1900s. But come February 14, Arizona will come to life once more.

That’s Arizona Statehood Day. At 7 p.m. that evening, the Arizona Centennial Theatre Foundation’s production of Arizona, as adapted by playwright Richard Warren, will be performed at the Tempe Center for the Arts and broadcast live on KTAR radio.

Both theatregoers and radio listeners will hear the words of that period, words that came directly from some of the participants, creating a theatre of the mind where the Old West still lives.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –