– Courtesy Library of Congress –

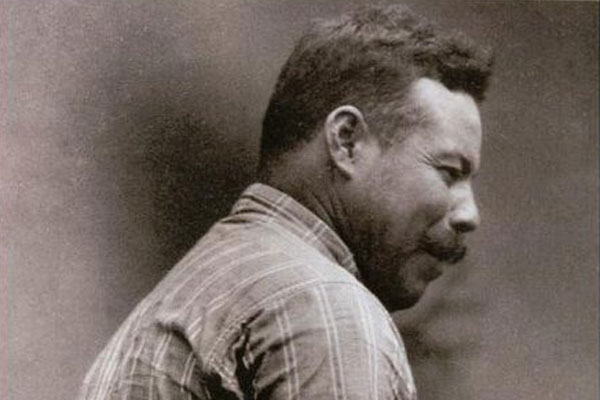

Raoul Walsh’s movie career began in 1912 and lasted more than half a century. A protégé of D.W. Griffith—he played John Wilkes Booth in Griffith’s 1915 film Birth of a Nation—Walsh acted in and directed more than 150 films, including John Wayne’s first big Western, 1930’s The Big Trail and the James Cagney 1939 gangster classic The Roaring Twenties, as well as 1941’s They Died With Their Boots On, with Errol Flynn, and 1941’s High Sierra, with Humphrey Bogart.

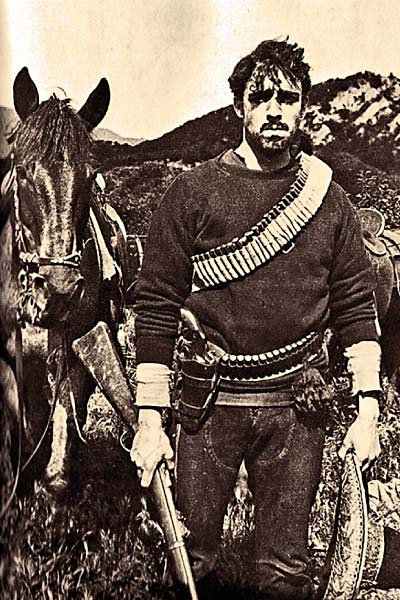

But no plot for any Walsh film was more improbable than the one he shot in 1914. Mexican Revolution Gen. Pancho Villa contacted Griffith’s Mutual Film Corporation to film a movie about the general with footage of real battles from Villa’s war with President Victoriano Huerta in northern Mexico.

“For the first time,” wrote Friedrich Katz in his monumental The Life & Times of Pancho Villa, “people who had never been involved in a war could actually see what war was like.”

Griffith dispatched 27-year-old Walsh to Mexico with the first monthly payment of $500 in gold, thus marking the Hollywood film studio as helping to finance the Mexican Revolution.

Walsh wrote in his 1974 memoir, Every Man in His Time, that Villa “reminded me of something wild in a cage.”

Demanding immediately to see the money, Villa took a $20 gold piece, turned it over in his fingers and dropped it back in the bag. The production was on.

For two months, Walsh shot film while dodging bullets and shrapnel. After filming Villa’s campaigns, Walsh returned to California and played the young Villa in early scenes for the film.

In the fall of 1914 and winter of 1915, The Life of General Villa garnered excellent business across the United States. Walsh watched the film, for which he had risked his life, at a theater in Los Angeles, not knowing that fate and politics would soon take his movie out of circulation forever.

Near the end of 1914, Villa’s cautious relationship soured with Venustiano Carranza, who had become president of Mexico after Huerta and Francisco Cházaro lost power. Carranza persuaded U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to cut off support to Villa. In March 1916, an enraged Villa crossed the U.S.-Mexico border and raided a U.S. Army supply depot in Columbus, New Mexico, killing 18 Americans.

In retaliation, Wilson ordered Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing to capture the rebel general. Pershing never caught up with the elusive Villa. Americans soon forgot about Villa and were swept up by events in Europe. On April 6, 1917, the U.S. declared war on Germany. In Mexico the long revolution drifted into a truce between Carranza and Villa until Carranza’s assassination in 1920.

This left an uneasy peace between Villa and Mexico’s next president, Álvaro Obregón. On July 20, 1923, while visiting the town of Parral, Villa was caught without his usual cadre of bodyguards and was killed by nine bullets shot by multiple gunmen believed to be acting with Obregón’s approval.

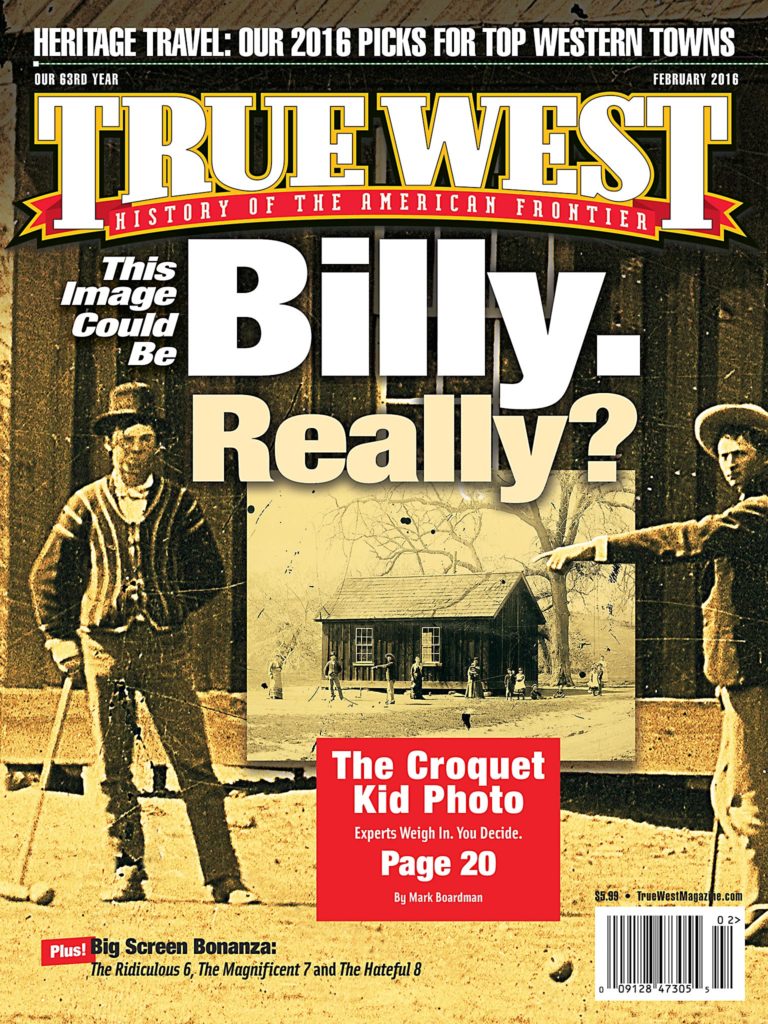

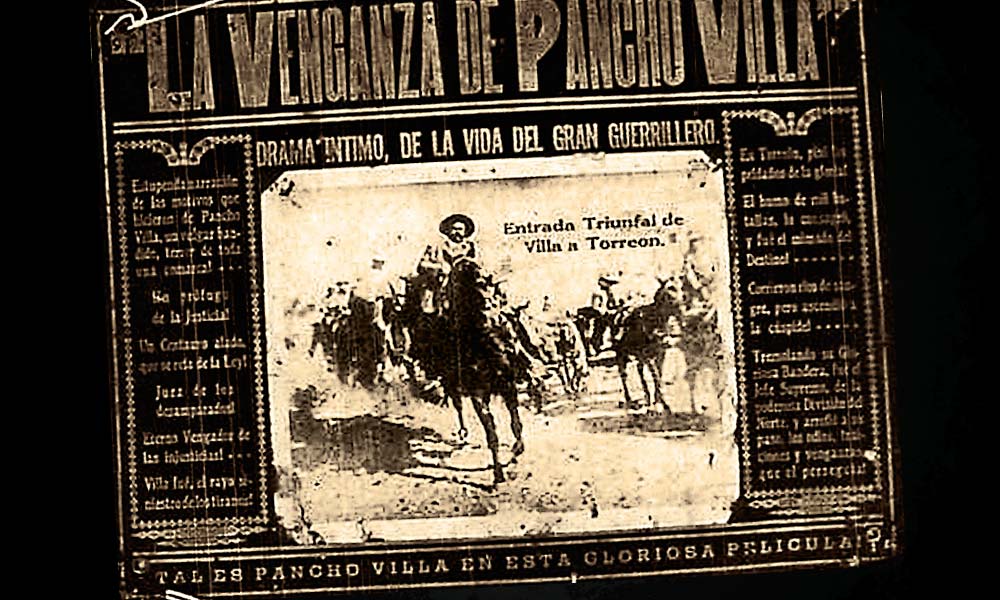

Throughout all this turmoil, Walsh’s film was lost to history. The Life of General Villa, though, had an unexpected afterlife. In 2003, Mexican filmmaker Gregorio Rocha released a remarkable documentary. The Lost Reels of Pancho Villa told the story of Rocha’s search for Walsh’s film. Rocha had combed film libraries in North America and Europe, unable to find a copy, but at the University of Texas in El Paso, he made a startling discovery. Edmundo and Félix Padilla, a father-and-son team who distributed films to Spanish-speaking American audiences in the 1920s and 1930s, had put together multiple films about Villa, with Edmundo releasing the definitive film in 1936, The Revenge of Pancho Villa, from segments of numerous silent films—especially The Life of General Villa.

In his film, Rocha’s voice is heard as the camera pans over a photograph of Villa: “I like to ask questions of old pictures. ‘Who are you standing there in front of the camera? Who took your picture? Where are you? What was going through your mind?’” And, finally, “So, Gen. Villa, what happened to the movie you shot in 1914?”

But neither Villa nor Walsh, who died in 1980, could have answered the question.

We do, at least, finally have a glimpse of Walsh’s film, in The Lost Reels of Pancho Villa, which can be seen in four installments on YouTube.

– Courtesy Mutual Film Corporation –

– Courtesy University of Texas in el Paso / Félix and Edmundo Padilla Collection –

Allen Barra is the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp. His latest book is Mickey and Willie: The Parallel Lives of Mantle and Mays. He is a columnist for American History and Civil War Times, and writes regularly for The Daily Beast.