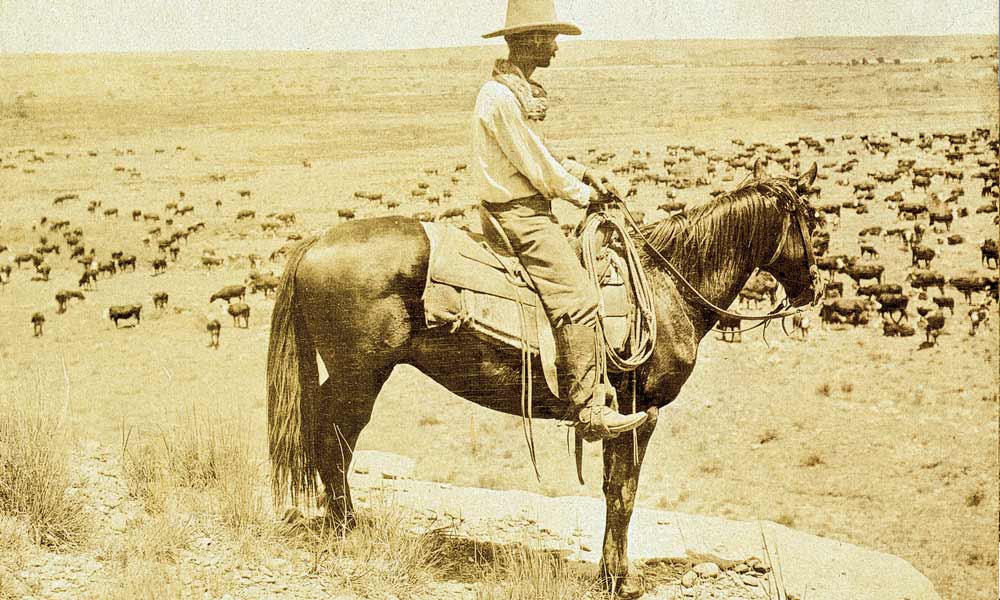

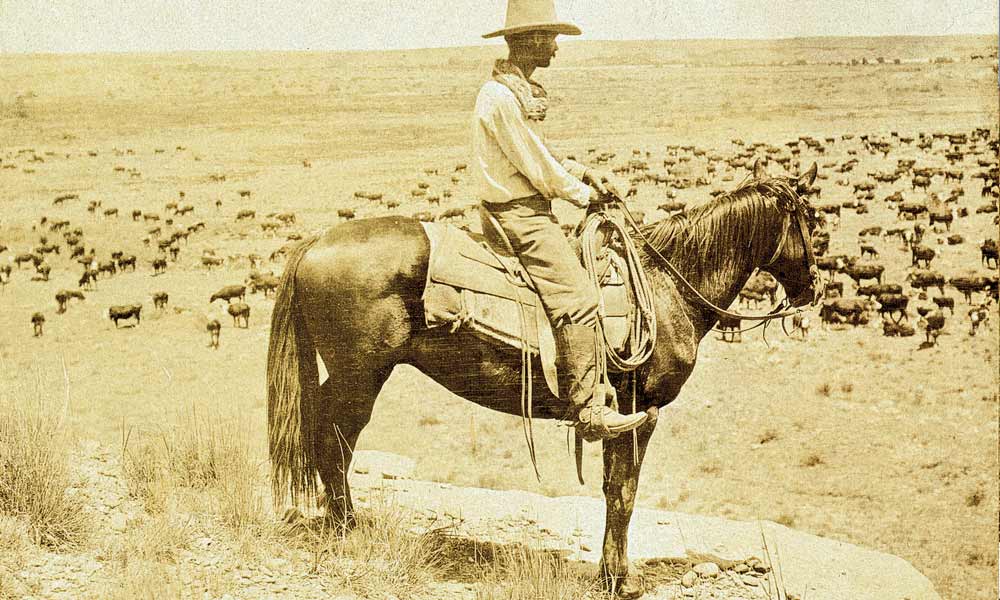

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Martin Scorsese once said, “More than 90 percent of directing is the right casting.”

Lonesome Dove is the greatest Western miniseries—no, to hell with the miniseries limitation: it’s one of the greatest Western movies ever made. And its greatness is because of its casting.

We know that Larry McMurtry wanted to cast John Wayne as Woodrow Call and James Stewart as Augustus “Gus” McCrae. This might have worked in, say, the way that Wayne’s star trip in 1969’s True Grit worked. But it wouldn’t have been great the way Lonesome Dove was great because Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall were not cast for their star power but because they were Woodrow and Gus.

Not to argue with Scorsese—our greatest director of Easterns—but only half of a movie’s success can be attributed to the actors. The other half is due to the script. McMurtry and William Wittliff wrote Lonesome Dove’s script, and it had the advantage of being taken from one of the three greatest of all Western novels. (Number one is Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man, while Charles Portis’s True Grit and McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove tie for a close second.)

The greatness of Lonesome Dove starts with its source material, and the material comes from a man who knew his subject.

In his essays on Texas, In a Narrow Grave, McMurtry correctly noted that movie Westerns “fault the myth when they dramatize gunfighting, rather than horsemanship, as the dominant skill.”

The killing in Lonesome Dove is invariably regarded with a wry salty humor of the kind that Mark Twain thought was essential to American storytelling (and which is woefully missing from Westerns by highly regarded novelists such as Cormac McCarthy). The novel’s famous first sentence, for instance: “When Augustus came out on the porch the blue pigs were eating a rattlesnake—not a very big one.”

McMurtry’s Texas Ranger McCrae can also be philosophical about killing, but without the pretension. “If I’d wanted civilization,” he says to his partner, Call, “I’d have stayed in Tennessee and wrote poetry for a living. Me and you done our work too well. We killed off most of the people that made this country interesting to begin with.”

McCrae anticipates Sigmund Freud’s argument in Civilization and Its Discontents by more than half a century.

McMurty’s tale is filled with sights and sounds and smells and observations about mundane subjects such as the superiority of biscuits cooked in a Dutch oven compared to those baked in an indoor stove: “A man that depended on an indoor cookstove would miss the sunrise, and if he missed sunrise in Lonesome Dove, he would have to wait out a long stretch of heat and dust before he got to see anything so pretty.”

Such observations could only come from a writer who knows the West firsthand and grew up with its traditions.

Actually, Scorsese was being modest about the director’s share of the credit for a great movie. One-third should go to casting, one-third to the script and source material, and one-third to the director, who has to put it all together. Neither before nor after Lonesome Dove was Simon Wincer a great director, but at the right time, he was great enough to know great actors and great words when they came his way.

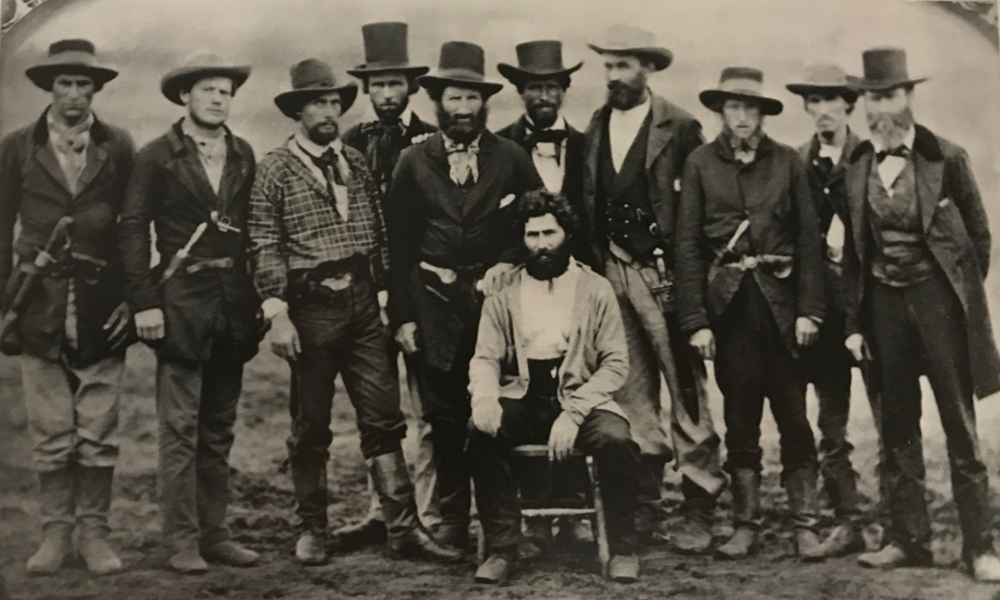

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Allen Barra is the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp: His Life and Many Legends. He writes about sports for The Wall Street Journal and is a contributing writer for American History Magazine and The Daily Beast. His last book, Mickey and Willie: The Parallel Lives of Baseball’s Parallel Lives, was nominated for the Pen Award for Literary Sportswriting.