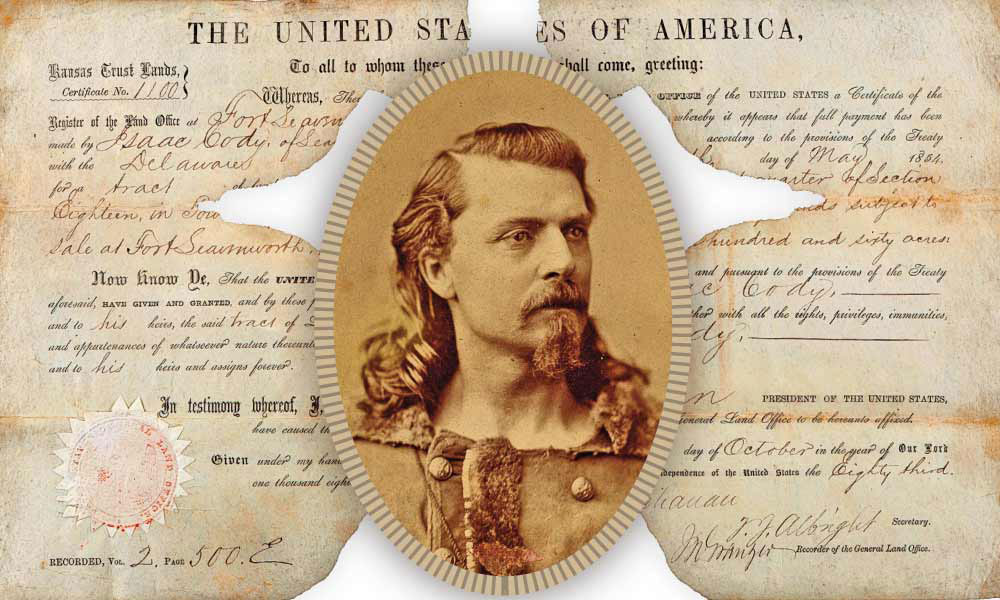

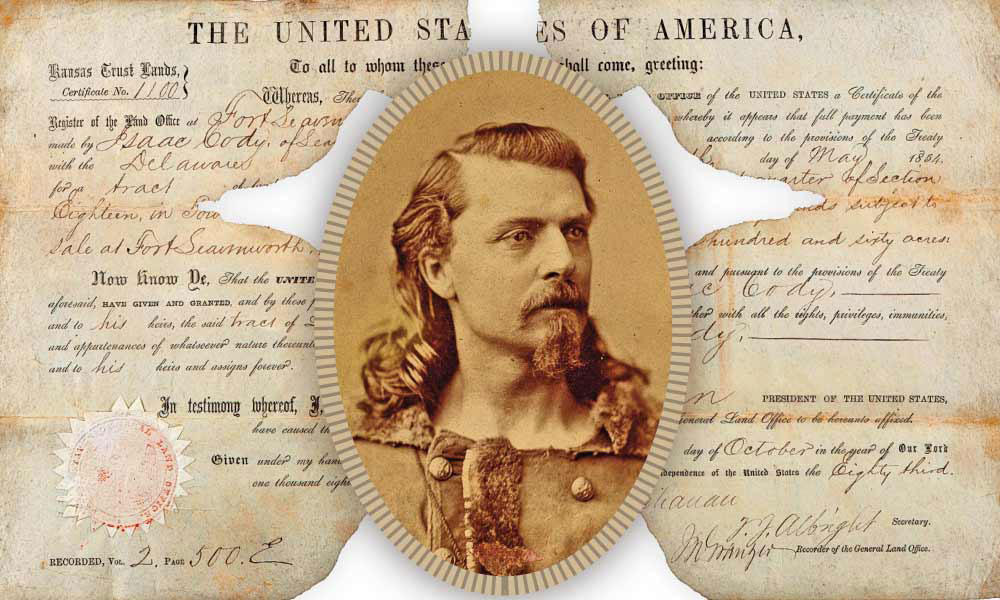

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions: certificate December 11-12, 2012; inset buffalo bill cody June 2008 –

The Kansas-Nebraska Act may have been the match that lit the fuse of the Civil War.

Some claimed the law was an effort by gutless bureaucrats to pass the slavery buck on to others. Congress—with pro-slavery Democrats in the majority in both houses—had effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise. That 1820 law allowed slavery only south of the 36-30 line (except for Missouri). But it hadn’t solved the political and social problems tied to slavery in new territories and states.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act created those two territories and then let citizens decide whether or not to allow slavery. Chaos

arose even before President Franklin Pierce signed the measure into law on May 30, 1854.

By then, numerous pro-slavery “border ruffians” from Missouri had made their way into Kansas, intent on influencing the

vote. The ballot box was just one way to make the decision—guns and knives were another.

One of the first casualties was Isaac Cody, who had brought his family to the Salt Creek Valley near Fort Leavenworth just before the act was signed. Cody was vocally anti-slavery. Cody’s pro-slavery neighbors forced him to publicly address his views that September—and he got stabbed twice! He died nearly three years later of complications related to the wounds. His son, William F. (later the legendary Buffalo Bill), was only eight at the time of the assault. He never forgot what happened.

In 1855, abolitionist John Brown moved to Kansas Territory to protect his sons and their families from the border ruffians. After a pro-slavery group ransacked Lawrence on May 21, 1856, Brown and company quickly sought vengeance. On May 25, they used broadswords to butcher five pro-slavery men along Pottawatomie Creek.

In retaliation, leader Henry Pate—the same man who had led the attack on Lawrence—captured two of Brown’s sons. Brown and 29 men beat and captured Pate and crew at the Battle of Black Jack on June 2.

On August 30, several hundred pro-slavery forces headed into Osawatomie, Brown’s hometown. Brown and a few dozen men fought back, but five Free-Staters were killed, including Brown’s son Frederick.

The violent tit-for-tat continued over the next two years, most often in guerrilla actions involving arson, looting and crop destruction. Territorial and federal officials failed to quell the violence—or even form a territorial legislature.

The last bad act of the “Bleeding Kansas” period came in May 1858. Charles Hamilton and 30 Missouri men captured 11 unarmed Free-Staters in Kansas. Hamilton and his forces opened fire on the prisoners, killing five, in what became known as the Marais des Cygnes Massacre.

In all, an estimated 59 people died in “Bleeding Kansas” between 1854 and 1859, setting the stage for the guerrilla warfare that ravaged Kansas and Missouri during the Civil War. The Kansas-Nebraska Act set in motion forces that its supporters couldn’t have imagined in 1854.