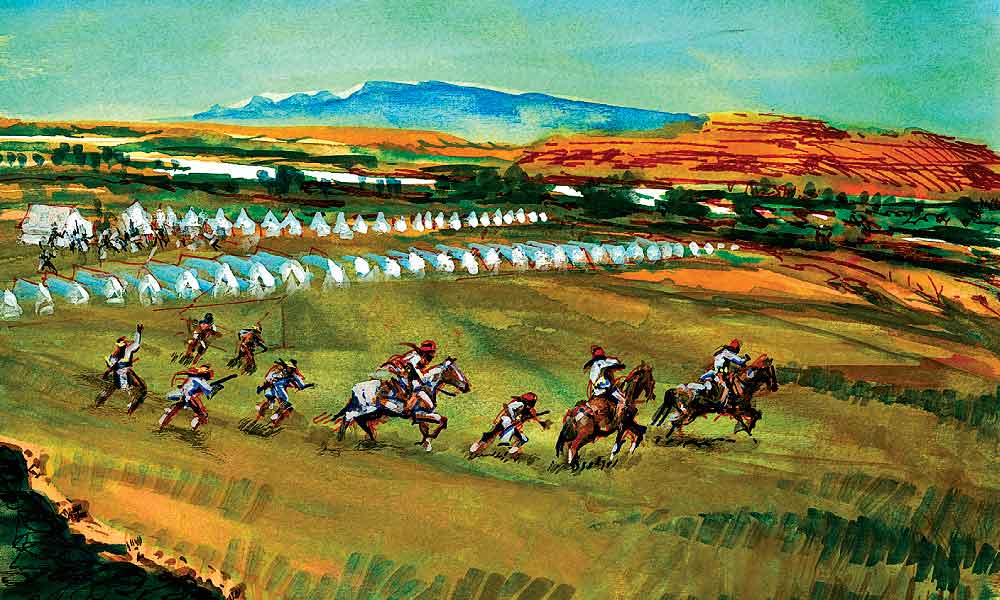

-Illustration by Bob Boze Bell-

June 1, 1887

Absent from duty for five days, the Apache Kid, along with four other Apache scouts under his command, ride single file into the Arizona headquarters of the San Carlos Reservation. The Kid was acting chief of scouts while Al Sieber was away at Fort Apache and the White River Subagency.

Upon his return to San Carlos, Sieber has summoned the Kid after hearing he killed another Apache in an alcohol-fueled family feud.

Told by a messenger that the Kid wants to powwow, Sieber contacts the commanding officer, Capt. Francis Pierce; two interpreters are also notified. The clock is approaching

5 p.m. as Sieber and Pierce proceed 75 yards on foot, from headquarters to Sieber’s tent, to meet the party.

Although the Kid and his men are carrying their arms openly, in direct violation of camp regulations, none of the men in Sieber’s party is armed. As word of the scouts’ arrival spreads, other Apaches from the nearby camps gravitate toward the tent, and some of them are armed.

Walking up to the scouts, Sieber says, “Hello Kid.”

Returning the greeting, the Apache Kid and his scouts dismount, with their weapons in their hands.

Captain Pierce asks, “Where are the five scouts who have been absent?”

The Apache Kid and the others step forward.

“Give me your rifle,” Pierce orders the Kid. The Kid complies.

Pierce demands his gun belt, which the Kid surrenders. The captain places the rifle against Sieber’s tent and the gun belt in a chair. He orders the other four to give up their arms and gun belts, which they do.

Pointing in the direction of the guardhouse, the captain barks, “Calaboose!” (Spanglish for jail). Several of the Indians pick up their gun belts and remove their knife scabbards.

Pierce and Sieber hear an “unusual commotion.” They turn to see mounted Indians loading their rifles. (The assembled Apaches later claim one of the interpreters, Antonio Diaz, had intimated, with Apache sign, that the arrested scouts would be sent to the “island,” which signified Alcatraz or even Florida; see quote on opposite page.)

Several of the disarmed scouts lunge for their weapons as Capt. Pierce jumps in between them, trying to shove their guns out of reach. The Kid makes a grab for his carbine, but Sieber grabs it with his right hand, while shoving the Kid with his left.

Unable to retrieve his weapon, the Kid runs around the tent and disappears.

“Look out, Sieber!” Pierce yells, “They are going to shoot!”

Sieber kicks the guns toward the tent as two shots ring out, one right after the other. Sieber and Pierce dive into the tent as bullets rip through the twin openings, from front to back.

Sieber grabs his weapon and runs out to engage the shooters. He fires at a mounted Apache who has just fired at him. But before Sieber can fire again, a .45-70 slug tears into his left leg below the knee, breaking the bone and knocking him flat. He crawls back into the tent as the Apaches disappear into the twilight.

The unexpected gunfight is over, but the long, tragic nightmare of the Apache Kid has just begun.

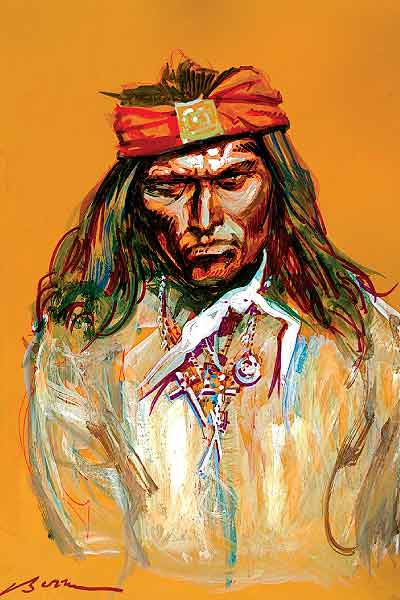

-Illustration by Bob Boze Bell-

Caught Between the Military and the Deep Blue Sea

Two companies of cavalry take the field within 15 minutes of the fight. They trail the Apaches for 15 miles along the San Carlos River (the Kid’s party includes about 17 members; some are on foot, as they are unable to find a horse in time). From the river, the fleeing Apaches turn south, through Aravaipa Canyon.

When the Apaches reach the San Pedro River, one of the renegades, believed to be a Yaqui, kills William Diehl near Mammoth Mill, 60 miles north of Benson. The band steals two horses and then strikes again, killing Mike Grace, whose body is found northwest of Crittenden.

After a feint toward Mexico, the Apache Kid’s band camps high on the Rincon Mountains (east of Tucson), where soldiers surprise them, capturing all of the Apaches’ horses and supplies.

After 24 days of running, the Kid surrenders. He is then tried, along with four scouts, by a military court.

The Kid and his scouts are found guilty and sentenced to death by firing squad, but Gen. Nelson Miles objects to the ruling and asks the court to reconsider its verdict.

On August 3, at Camp Thomas, the reconvened court resentences the five to life imprisonment, which Miles reduces to 10 years. Under heavy guard, the convicted scouts, including the Kid, are delivered to Alcatraz, in California’s San Francisco Bay, to serve their time.

Upon military review of the case, which reveals prejudice among officers on the jury, the Kid’s sentence is overturned, and he is sent home after serving 16 months.

Angry Arizona civilians convince the courts that the military had no jurisdiction in the case. By the close of 1888, the Kid and his comrades have been ordered back to San Carlos.

A new trial is held in Globe, and Al Sieber is the chief witness against the Apaches. Not surprisingly, the jury declares all the defendants guilty, and the judge sentences them to seven years in Yuma Territorial Prison.

The Apache Kid and other prisoners are gathered for transport to Yuma, via Riverside and the rail station in Casa Grande. Sieber offers Sheriff Glenn Reynolds the use of an Army escort, but the sheriff declines. It costs him his life.

A Daring Escape!

On November 1, 1889, Sheriff Glenn Reynolds is transporting the Apache Kid and eight other prisoners who will be put on the train in Casa Grande, Arizona, to take them to the Yuma penitentiary. It is a rough, two-day stage ride from Globe to Casa Grande. The weather is cold and wet, and snow is in the forecast.

On the second morning, four miles out of Riverside (see below map), the stage encounters Ripsey Wash, followed by a steep incline. The sheriff and his hired guard, William “Hunkydory” Holmes, exit the stage, along with seven of the prisoners. With only the driver, Eugene Middleton, and two prisoners aboard (including the Kid), the horses struggle, but successfully make it up the soggy and steepest part of the ridge. It is snowing.

As Middleton and his coach clear the grade, he hears men scuffling behind him, then two shots. At first, he is not alarmed; the sheriff was target shooting earlier. When Middleton looks back, though, he cannot see anything through the brush.

A Mexican prisoner, Jesus Avott, frantically runs up, explaining that the Indians are trying to kill him. Middleton tells him to get on the stage. As Avott raises his foot to get in, one Apache prisoner, Bach-e-on-al, runs up, brandishing Holmes’ rifle. He fires, hitting Middleton in the face, and the driver topples to the ground.

The newly freed prisoners bring up the keys and unchain the Kid. They debate whether to crush Middleton’s skull with a rock (popular legend says the Kid stops them because Middleton had shared a cigarette with the Kid the night before at Riverside Station).

Grabbing ammunition and money, the escapees cut the horses loose and scatter into the wilderness. Avott walks to Florence to seek help for Middleton. For this act, the charges against him are dropped.

Middleton, incredibly still alive, makes his way toward Riverside to secure help in recapturing the prisoners. A subsequent posse is thwarted by a snowstorm that obliterates the fugitives’ tracks.

Paul Andrew Hutton found this rare photo while researching his new book, The Apache Wars. It shows the Apache Kid (back row, right) and other prisoners. The back states the photograph was taken in Globe, Arizona, which is where the Kid and others were tried.

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –

The Prisoners, Prior to Their Bold Escape

After a group of Apache defendants is found guilty in a Globe courtroom, they are photographed (above) before they depart for the Yuma Territorial Prison. Note that the Apache Kid (standing, second from right) is still wearing his brass reservation tag on his left breast pocket.

When the Apaches get out of the stage near Ripsey Wash, Bach-e-on-al (front row, center, indicted under the name Pash-ten-tah) allegedly slips free of his handcuffs. He and El-cahn (standing, far left) overpower the sheriff as another two Apaches attack Holmes, who reportedly dies of a heart attack before being shot. Hos-cal-te and Say-es (standing, second and third from left) are later recaptured and die in prison. Not shown is prisoner Jesus Avott, sentenced to one year in prison for selling a friend’s horse for $50; he is the only prisoner who attempts to help the wounded Middleton.

The Fallen Lawmen

While transporting the prisoners via stage, Sheriff Reynolds (right) carries a Colt .45 and a double-barreled shotgun loaded with buckshot. For the journey, he turns down the offer of a scout escort, allegedly telling Al Sieber, “I can take those Indians alone with a corncob and a lightning bug.” He begins the trip on his horse, which he leaves in Riverside. Had he been on horseback during the Apache revolt, he may have averted the disastrous outcome.

Hunkydory Holmes (bottom right) carries a lever action Winchester and a pistol on the trip. (Middleton also carries a pistol.) On the ill-fated journey, Holmes allegedly takes it upon himself to cheer up the prisoners by sharing his original poetry. Here are a few lines:

Oh, I am a jolly miner lad,

Resolved to see some fun sir,

To satisfy my mind

To Phoenix town I came sir

Oh, what a pretty place

And what a charming city

Where the boys they are so gay

And the squaws they are so pretty

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Military and civilian authorities launched a colossal manhunt for the escapees. By the summer of 1890, all the fugitives had been killed or captured—all except the Apache Kid. By 1892, the State of Arizona offered a $6,000 reward for the Kid, and several officers were commanded to bring in the Kid, dead or alive. No one ever claimed the reward.

Eugene Middleton survived his face wounds and ran the Riverside stage station for several years. He then moved to Globe, where he owned a successful apartment building. He died in 1929 of natural causes. He was 68.

Some historians believe that the Kid escaped into the Sierra Madre Mountains in Old Mexico where he lived out his life.

In 1937, Norwegian explorer and anthropologist Helge Ingstad heard that renegade Apaches still lived in Mexico. Traveling deep into the Sierra Madres, Ingstad claimed he found a woman, Lupe, who was thought to be the daughter of the Apache Kid.

Recommended: The Apache Wars by Paul Andrew Hutton, published by Crown; The Apache Kid by Phyllis de la Garza, published by Westernlore Press.