American Indians called the Sharps buffalo rifle the “Shoots Far Gun,” or the gun that “shoots today and kills tomorrow,” and for good reason. In the hide-hunting years of the 1870s, the heavy Sharps rifle was the “buffalo gun” of choice with many hide men. While they made most of their shots at around 200 yards or less, the savvy buffalo hunters realized that when hunting in Indian country, they should keep about 10 cartridges set aside for self-defense. With these few rounds, they were able to keep hostile tribesmen at a safe distance from their bows and arrows and many of their firearms, until they made it back to camp.

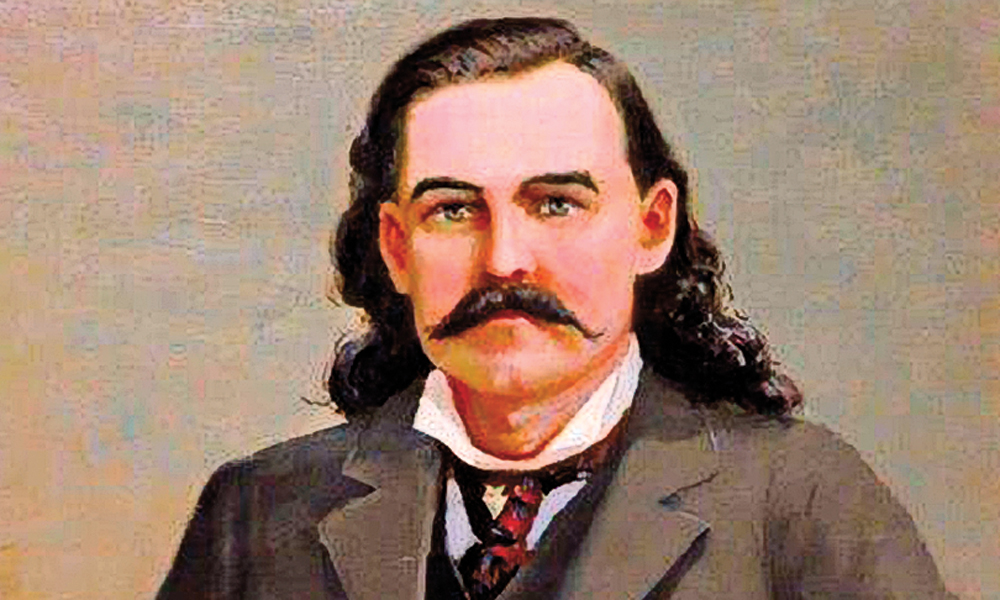

A well-recorded example of the Sharps’ great range was during the June 1874 Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle, when a group of Indians rode out on a bluff nearly a mile distant from the hunters to survey the situation. Billy Dixon, who was already well known as a crack shot, was persuaded to try firing at them. He took aim at one with a “Big Fifty” Sharps, borrowed from one of the other hunters, and cleanly dropped a warrior from atop his horse, thus ending the fight. It measured at 1,538 yards!

Although Dixon himself claimed it was a “scratch shot,” many modern shooters try to debunk his shot. Among modern-day nonbelievers was a forensic scientist who claimed a .50-90 Sharps could not throw a bullet out that far. In response to this technician’s curiosity and disbelief, in the fall of 1992, fellow gun writer and long-time amigo Mike Venturino was invited, along with the folks from Shiloh Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company, to travel to the Yuma Proving Grounds in Arizona, to use some then-newly declassified radar devices to test the performance of several types of ammunition.

Using a machine rest modified from a gun carrier from a Russian T-72 tank, they started firing away. For the first Sharps shot, with the gun carriage elevated to 35 degrees, a 675-grain bullet, pushed by 90 grains of FFg black powder, and with a muzzle velocity (mv) of only 1,216 feet per second (fps) launched the bullet over 3,600 yards distant. That’s 10,800 feet—over two miles! The scientists couldn’t believe it, so a second round was touched off. This time the lead projectile weighed 650 grains with a mv of 1,301 fps. Using the same 35-degree elevation, the bullet landed 3,245 yards away. When one of the mathematicians calculated some data he suggested they reduce the elevation to about 4½ to 5 degrees to duplicate Billy Dixon’s shot. When this was done using the same load, the lead slug landed 1,517 yards downrange—almost the exact range of Dixon’s controversial shot. A five-degree muzzle elevation can easily be achieved with only the rear barrel sight on a Shiloh Sharps. This writer has made similar long-range shots with his own .50-90 Shiloh Sharps, using 90 grains of FFg black powder and a 515-grain bullet, while testing firearms for Guns & Ammo magazine.

According to Venturino, with 35 degrees elevation, the bullet gained a maximum height just short of 4,000 feet and was airborne a full 30 seconds. In my own experimentation with my Big Fifty Shiloh Sharps at similar distances, I found that with the slight muzzle elevation of around five degrees, I counted three full seconds between firing the shot and seeing the bullet kick up dirt in the target area. So the next time some modern gun “expert” wagers that you can’t put a bullet a mile out with a Sharps buffalo gun—take the bet!

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger Collection –