– True West Archives –

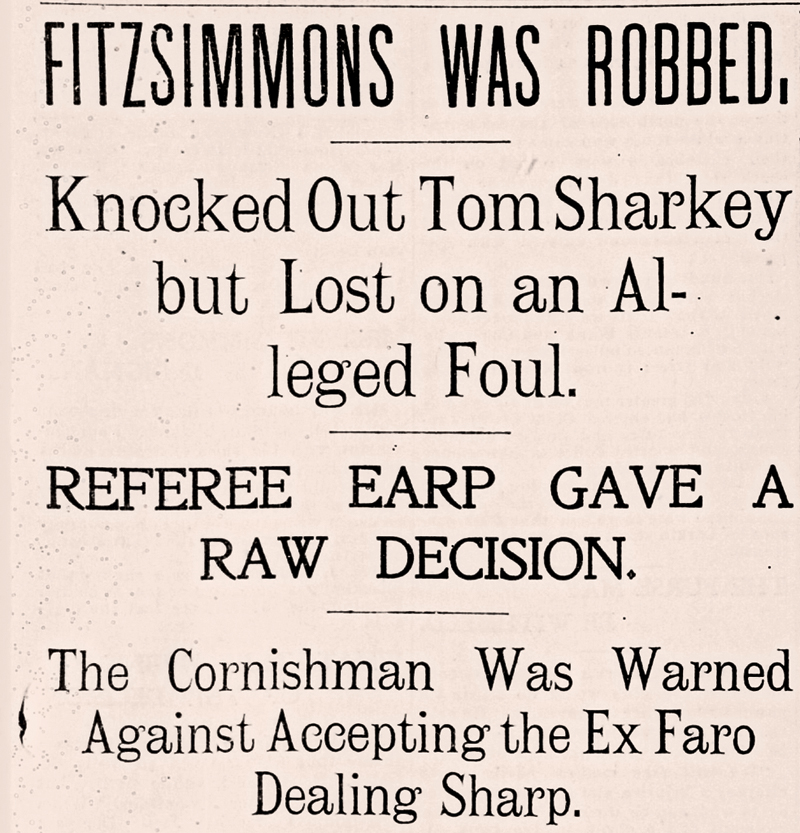

For more than a century, the Thomas Sharkey versus Robert Fitzsimmons fight of 1896 has been an ugly blemish on the complexion of Wyatt Earp. Dozens of historians have argued both sides of the story: Earp threw the fight, or the foul was a correct call. Finally, in a recently discovered newspaper article, Earp himself explains what happened.

In April 1897, Earp befriended Tom Sharkey and, according to newspaper accounts, would serve as his corner man at the upcoming Sharkey versus Peter Maher fight. Yet Earp was not in Sharkey’s corner during the fight as the newspapers had projected. Prior to the fight, Earp sensed the contest was going to be anything but fair. Earp returned to San Francisco, California, on June 4, five days before the fight. Upon arrival, he told The Los Angeles Times that the event was fixed, and “that the fight had been arranged for Sharkey to win on the same principal as Sharkey’s fight with Fitzsimmons.” What a bombshell! So how does his statement fit into both fights?

THE SAILOR FOUGH FOUL

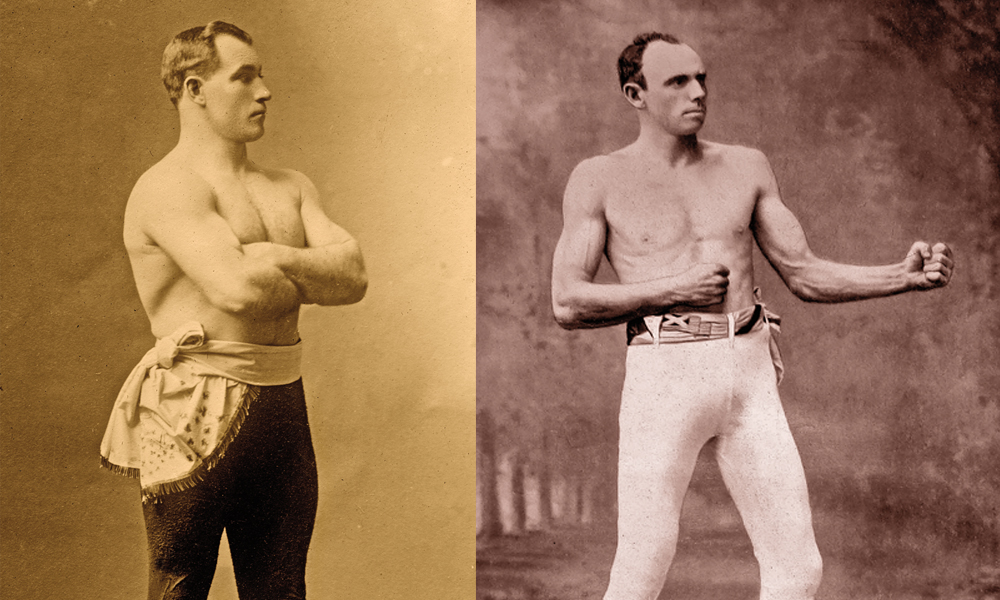

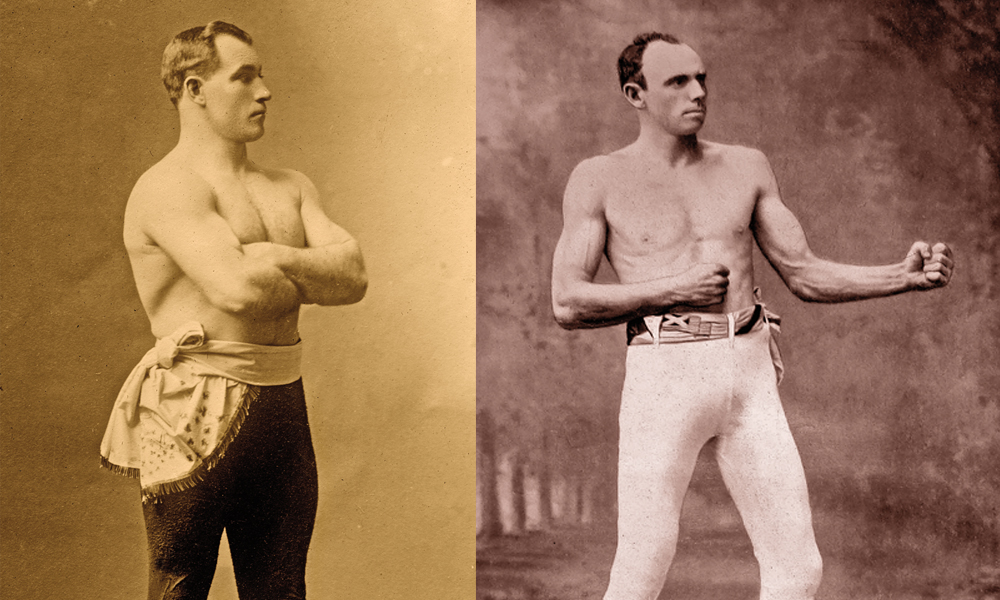

On December 2, 1896, Earp refereed the Tom “Sailor” Sharkey versus Robert “Ruby” Fitzsimmons world heavyweight championship fight at Mechanics’ Arena in San Francisco. The fight turned out to be the most humiliating event of Earp’s life. He was caught wearing a handgun while entering the ring and was forced to disarm before the fight could proceed. Earp was later accused of fixing the fight when he called a foul against Fitzsimmons for a low punch and awarded the fight to Sharkey.

During the post-fight litigation, Earp denied all wrongdoing and repeated that he had called a square fight. Some believe the publicity Earp received from this notorious affair exceeded that of the Fremont Street gun battle in 1881, also known as the Gunfight Behind the O.K. Corral.

After the fight, Fitzsimmons and his manager, Martin Julian, filed a formal complaint against Sharkey, the National Athletic Club and others. Earp was not included. The complaint alleged that the fight was fixed. A restraining order was granted that blocked Sharkey from receiving the $10,000 purse. After testimony from many involved in the fight, Superior Court Judge Austin A. Sanderson ruled the fight was technically illegal and therefore the court would not recognize the injunction.

THE REMARKABLE REFEREE

Earp felt betrayed by the sporting crowd and vowed to quit and return to a simpler life. His contemplation of this matter was short-lived; on March 16, 1897, he was seen in Carson City, Nevada, at the pre-fight festivities for yet another fight. While at the James “Gentleman Jim” Corbett versus Fitzsimmons fight, Earp accompanied Sharkey and manager Dan Lynch. The Los Angeles Times reported, “Earp looked as modest and unassuming as ever, with the same old suspicious bulge in his coat tails and the smile of self-satisfaction on his countenance.”

In April 1897, the press announced that Earp had assumed the role of Sharkey’s advisor and manager. Sharkey was desperately in need of a fight to prove that he was qualified to fight reigning world champion James Corbett. The Sharkey camp contacted Peter “Irish Giant” Maher to arrange a match. Earp would not only assist Sharkey in preparation, but also would be his principal second in the ring.

Later that month, Earp and Sharkey headed east on the train to New York. Along the way, the men stopped in Yuma, Arizona, to visit with Earp’s many Yuma friends. The San Francisco Call, while reporting Earp’s whereabouts, sarcastically referred to him as a “remarkable referee and all around sport.” Even The Oasis newspaper in Arizola took a shot at Earp when it proclaimed he was an “all-around tough citizen and Arizona is well rid of him.”

The Sharkey-Maher fight was arranged to occur on June 9, 1897, at the Palace Athletic Club in New York City. The contest had serious consequences for Maher also. A win meant financial backing he could use to pursue a match with Fitzsimmons.

On the evening of June 9, a crowd of 7,500 people filled the Palace Athletic Club. A purse of $12,000 was offered to the winner. A worldly cosmopolitan crowd showed up for the fight. Hundreds of Wall Street types, famous actors and others of the upper strata of society were in attendance. New York City’s The Sun stated that the group “sat quietly and orderly as they would in their pews at church.”

Unfortunately for fight fans, the event was to be run under the Horton Law, New York’s newly enacted ordinance, which expressly prohibited roughness or brutality. Contestants were only allowed to spar for points. Chief of Police Peter Conlin promised that at the first sign of brutality, the fight would be stopped and the men arrested.

Conlin’s threat lacked credibility since the police enforced the Horton Law selectively. For example, in the Peter Maher versus Joe “California Terror” Choynski fight held the previous December, Maher brutally “put the Californian to sleep.” The New York Police Commissioner watched the match from his front row seat and later remarked he had seen nothing brutal about the fight. The commissioner happened to be a then little-known man by the name of Theodore Roosevelt, the future 26th president of the United States and a boxing fan.

The night of June 9 began in a similar manner. During the first fight of the evening, Charlie Roden of Jersey City versus local boy Bobby Quaide, Roden knocked Quaide down twice with powerful punches to the jaw. By the second round, both men were staggering around the ring, much to the delight of the fans. After a particular harsh volley of punches to the jaw by Quaide, Referee Charley White stopped the fight in favor of Quaide. The police never got involved.

POLICE RUSHED THE RING

Sharkey and Maher entered the ring to the applause of the huge crowd. Both men were polite, smiling openly, and greeted each other in a friendly manner. The first rounds of the fight were likewise friendly. The men sparred like game chickens, throwing probing blows at each other. The crowd noted Sharkey was not aggressive as he had been during the Fitzsimmons fight.

Fireworks started in the sixth round. Sharkey hit Maher in the mouth, and as Maher was reeling, Sharkey nailed him hard on the neck with a right. Maher tumbled headlong and almost fell through the ropes. He was down five seconds, and when he got up, his lip was bleeding. Sharkey’s corner man, Choynski, gave him advice, and Sharkey did not rush in. The crowd was in uproar, and the police edged toward the ring.

In the seventh round, Maher spoke to the “Sailor” in a low tone. What he said could not be heard, and Sharkey did not respond. Maher then started forcing tactics for the first time. It was apparent Maher had been playing with Sharkey. Sharkey was now using both hands to slow the advancing Irishman.

– Published in The San Francisco Call, December, 3, 1896 –

Maher shot a terrific right-hander square on Sharkey’s chin. Sharkey was near the ropes and left the floor, landing flush on his posterior with a jolt that shook the ring. He sat dazed for a moment and then drew himself up on the ropes. Maher was on him like a tiger, and they were fighting furiously when the bell rang. Neither man stopped at the bell.

The police rushed the ring and arrested everyone in the roped enclosure. The fighters and their seconds were furious when they realized what had happened. Authorities took the combatants to their dressing rooms.

Sharkey’s seconds brought out Referee James Colville to render a decision. A draw was called. Announcer Charles Harvey conveyed the decision to the crowd. Everyone left in an ugly mood.

The principals, seconds, timekeepers and the referee were all arrested and locked up, but were bailed out an hour later. Steve Brodie posted the $500 bail for Referee Colville, Sharkey and his manager, Lynch. This fueled the rumor circulated by The San Francisco Call that all, including Earp, were in cahoots together. The Call stated that everybody knew that if Sharkey should fail at any point to lead, and his chances of defeating Maher were unlikely, the police would interfere and stop the fight. The paper described the fight as a “very unsatisfactory contest.”

The next morning, the fighters were arraigned before the Magistrate Robert Cornell. Cornell voiced his opinion that the fighters had acted disorderly, but within the law. When Mayor William Lafayette Strong was interviewed, he said he was against the Horton Law, because distinguishing between scientific sparring and prizefighting was hard to do, but that he believed the police had acted in good judgment.

FOOL ME TWICE, SHAME ON ME

The arbitrary enforcement of the Horton Law allowed the police to control any prizefight, for any reason they desired, including the improvement of their financial situation. Earp admitting the fight was fixed pre-fight further confirms he knew of and could have been involved with the arrangement. His public airing of this fact indicates he learned from the Sharkey-Fitzsimmons fight and didn’t want to be in the middle of that hornet’s nest again.

How does this all relate to the Sharkey-Fitzsimmons fight? Likely possibilities of what happened during that fight include: the fight was fixed, and Earp was in on the affair; Fitzsimmons did foul Sharkey, and Earp made the correct call; or Sharkey pretended to have been hit below the belt and convinced Earp of the foul.

Little-known information regarding Earp’s involvement was published by Charles Fernald in the 1951 edition of the Chicago Posse of the Westerners Brand Book. In his article, “Wyatt Earp in Alaska,” Fernald wrote of traveling on a ship to Alaska with Earp. Fernald claimed Earp told him that iodine had been injected into Sharkey’s groin to simulate the injury. Furthermore, Earp added he didn’t know about the iodine trick until sometime later. This statement is consistent with an opinion rendered by Dr. David Lustig, who, post-fight, examined the injury. Lustig testified the swelling of the area was not indicative of the alleged cause of the injury.

The Los Angeles Times article published on June 4, 1897, is an important piece of information, which, in conjunction with Fernald’s article and other details of the Sharkey-Fitzsimmons fight, certainly suggests the fight was fixed. Furthermore, Earp’s newly developed friendship with Sharkey post-fight adds fuel to the theory that Earp was in on the fix. Why else would he befriend the central person in a scandal that had caused him so much embarrassment and humiliation?

Earp never refereed another prizefight. In July 1897, he and paramour Josie returned to Yuma, Arizona, searching for the good life away from the public eye. A new chapter had begun in the life of the “Lion of Tombstone.”

Garner A. Palenske is a historian and author. Previously unpublished information regarding Wyatt Earp’s time refereeing prizefights in San Diego and along the Mexican border can be found in his book, Wyatt Earp in San Diego: Life After Tombstone. Palenske thanks author Casey Tefertiller for his assistance locating the Chicago Posse of the Westerners Brand Book.