In 1870, descriptions of the natural wonders from the Yellowstone area were often seen as fantasy. Truman C. Everts, age 54, joined the Washburn Expedition, the second of three important explorations of Yellowstone, to find out if the wonders were real. The former assessor of Internal Revenue for Montana, Everts was an unlikely explorer, and he approached the expedition as a vacation.

In September, the 19-man expedition was exploring the territory around Yellowstone Lake in present-day Wyoming. The nearly impenetrable forests made occasional separations between group members almost routine. On September 9, Everts found himself alone. Believing he knew the way, he rode on. As night fell, his companions fired signal shots, but Everts never heard them.

On September 10, Everts continued riding through the dark forest, confident that he would reunite with the party. When he dismounted to assess the path, his startled horse ran away, taking with him Everts’s survival gear. He was left with only the contents of his pockets (knives, a fishhook and opera glasses) and the clothes on his back.

A cold, fireless night slumbering upon pine needles convinced Everts that he might be in danger. In the meantime, his companions continued to search for him, but Everts had wandered beyond where they believed him to be.

Henry Washburn had previously recommended a rally point at the hot springs on the southwestern arm of Yellowstone Lake for anyone who got lost. Everts got turned around while trying to locate it, a circumstance that became clear to him when he reached Heart Lake.

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

Instead of heading toward the rally point, he remained for days, impotently watching a smorgasbord of mammals and huge flocks of game birds as his hunger deepened. He fretted about being captured by Indians, but soon prayed for Indians to find him. The first of many hallucinations crept into his mind as he envisioned a pelican to be an Indian paddling a canoe.

Everts stayed alive by eating thistles, a species that was later named in his honor, scavenging the wing of a gull and by eating a snowbird he had caught. His ordeal lasted weeks and encompassed about as wide a range of survival situations as experienced outdoorsmen encounter in a lifetime. He suffered through storms, freezing nights, close encounters with wildlife and injuries. All through this, the staggering beauty of Yellowstone never ceased to enthrall Everts.

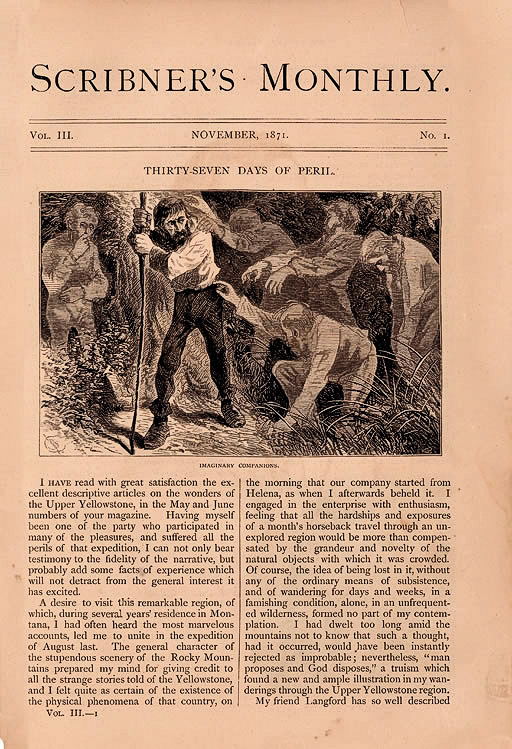

During his ordeal, Everts escaped a mountain lion by climbing high up in a tree. The cougar circled at the base of the trunk while the terrified Everts shouted and pounded sticks in attempts to frighten the beast. He clung to his perch as the creature roared out of the dark at him for hours before it left for easier prey.

Staying near the hot springs, he used them for warmth and to cook his thistles. One night, the crust around a vent collapsed and the steam scalded his hip. This painful injury required him to sleep sitting up.

Everts had not yet come up with a way to create fire. Then he figured out that, on sunny days, his opera glass lens could ignite fire. The ability to make fire was a blessing and a curse. One night, popping and crackling noises awakened him. His campfire had spread to the trees. He was surrounded by a ring of flame, with his left hand badly burned and hair mostly singed off. Everts barely escaped with his life, and in his starvation-induced, dreamlike view of existence, he saw the episode as “terribly beautiful.” The fire cost Everts his knives and fishhook.

As the days went on, Everts continued to suffer from “strange reveries” of the imagination. He hallucinated Indians, forest monsters and ghosts. He imagined his limbs and organs had changed into companions with whom he would converse and argue. While in the depths of his hallucinations, he chanced a unique survival technique. Finding a bear’s den, he built a fire around it and spent the night peacefully slumbering within as the fire spread to the forest all around.

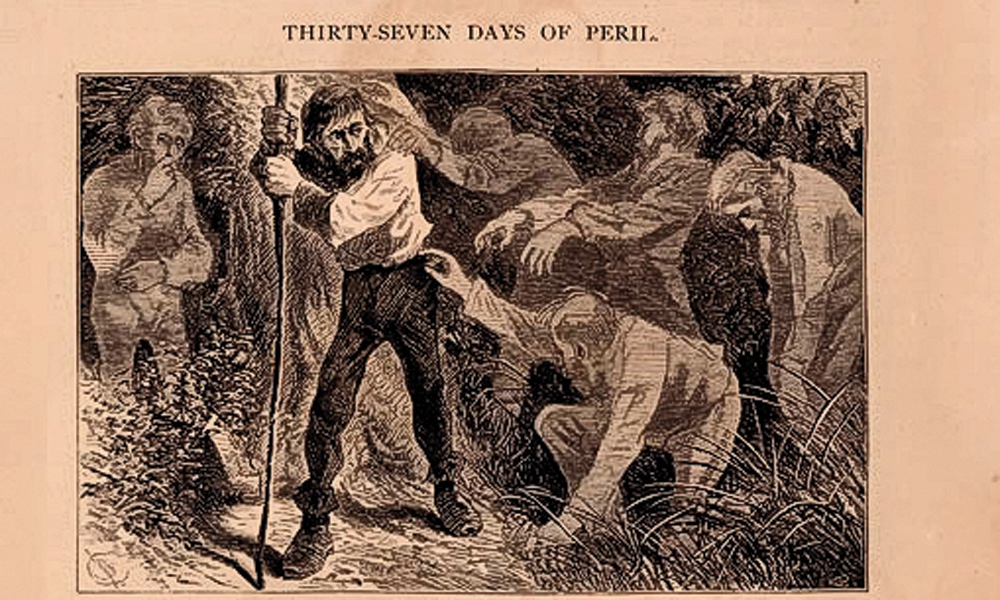

Thirty seven days into his ordeal, on October 16, during a sleet storm, Everts had a vision that turned out to be real—reward seekers Jack Baronett and George A. Pritchett. They rescued the delirious, 55-pound walking skeleton and took him to safety.

Everts later wrote of his ordeal and of the natural wonders of Yellowstone. Apparently none the worse for wear, he lived into his 80s, siring a child at the age of 75. What started out as a vacation in one of America’s most famous vacation places today had become one of the most celebrated survival experiences in the West.

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.