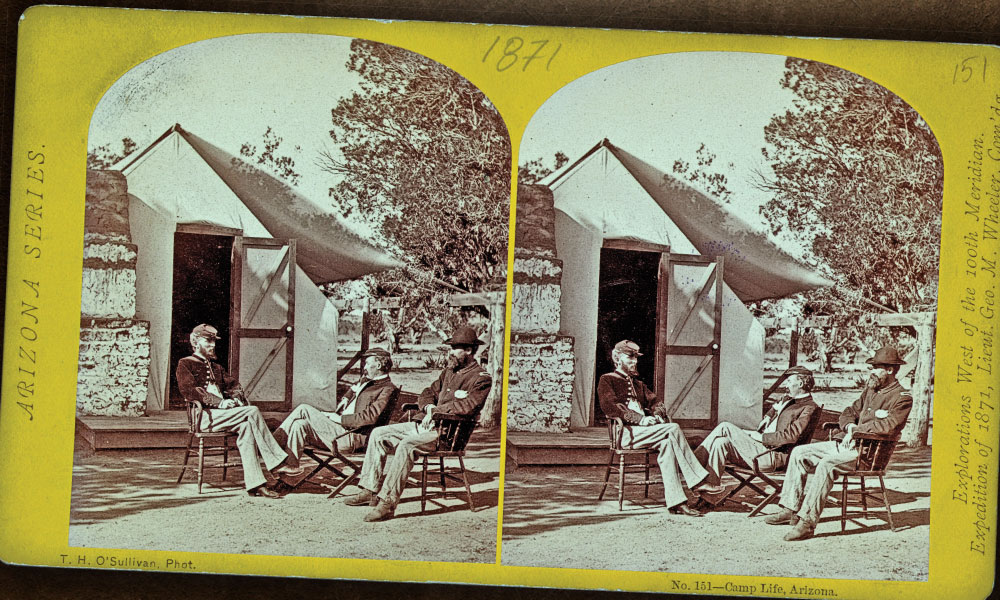

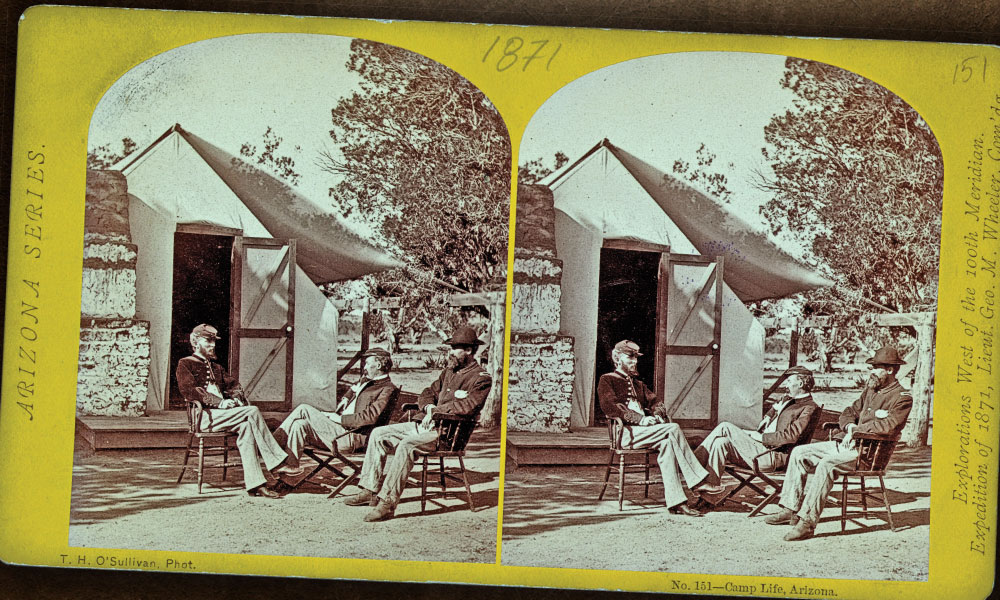

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

In March 1875, Brig. Gen. George Crook—on his way out of Arizona to take over as commander of the Department of the Platte—enjoyed a “farewell hop.” A hop? Somehow I have trouble picturing George Crook, in pith helmet and gum coat, dancing with wife Mary to Danny & the Juniors.

Well, this was Prescott—which Crook’s adjutant, John G. Bourke, described as “a village transplanted bodily from the centre of the Delaware, the Mohawk, or the Connecticut valley”—but Crook wasn’t at The Palace Restaurant & Saloon (which wouldn’t open until September 1877) on Whiskey Row. He was at Fort Whipple, being feted for his successful campaigns against the Yavapai and Tonto Apaches.

After serving in the Platte and during the Great Sioux War of 1876-’77 [see Sidebars, pages 44 and 46], Crook would return to Arizona in 1882 for the Apache Wars. But when he left again, there would be no hops in his honor.

George Crook, of course, was not just an Arizona figure. Born in 1830 in Ohio, he graduated from West Point in 1852—nowhere near valedictorian, by the way—and served in California and Oregon before the Civil War. After the South surrendered, he returned to the Pacific Northwest for the Snake War before President Ulysses S. Grant sent him to Arizona and made him a brigadier general.

It’s called Press-kit

So Prescott, still one of the West’s most Western towns, is a good place to start trailing the general with stops at the Sharlot Hall, Phippen and Smoki museums, and, naturally, the Fort Whipple Museum, a 1909 officers’ quarters on what’s now the VA Hospital grounds.

From Prescott, head to Camp Verde, one of the key posts during the Yavapai/Tonto/Apache War (psssst…I highly recommend pie lovers detour south on I-17 to the Rock Springs Cafe in Rock Springs before moving north on the interstate to Camp Verde).

The war started on April 30, 1871, with the Camp Grant Massacre. Americans, Mexicans and Papago Indians attacked a sleeping camp of Apaches, most of them women and children. Butchery followed. Women were raped. Almost all of the dead—the lowest estimates say no fewer than 85—were mutilated. Twenty-seven children survivors were

sold into slavery. Newspapers praised the slaughter. Three ringleaders were elected within a month to high office in Tucson.

But the massacre might have led President Grant to replace Col. George Stoneman, commander of the Department of Arizona, with Crook.

Arriving in Tucson—“the nights were so hot that it was impossible to sleep, and we would get up in the morning almost as tired as when we went to bed,” he wrote—Crook soon journeyed north. With his “Destroying Angels,” the 3rd Cavalry, and Apache scouts, he took the war to the Apaches in their rugged country.

I’m standing on the porch of the commanding officer’s quarters at Fort Verde State Historic Park in Camp Verde, the 1½-story adobe covered with board and batten where Tonto Apache Chief Cha-lipun and 300 of his followers surrendered on April 7, 1873.

“[T]he copper cartridge has done the business for us,” Cha-lipun told Crook, who noted the wretched conditions of the Apaches, “emaciated, clothes torn in tatters, some of their legs not thicker than my arm.”

Trailblazing

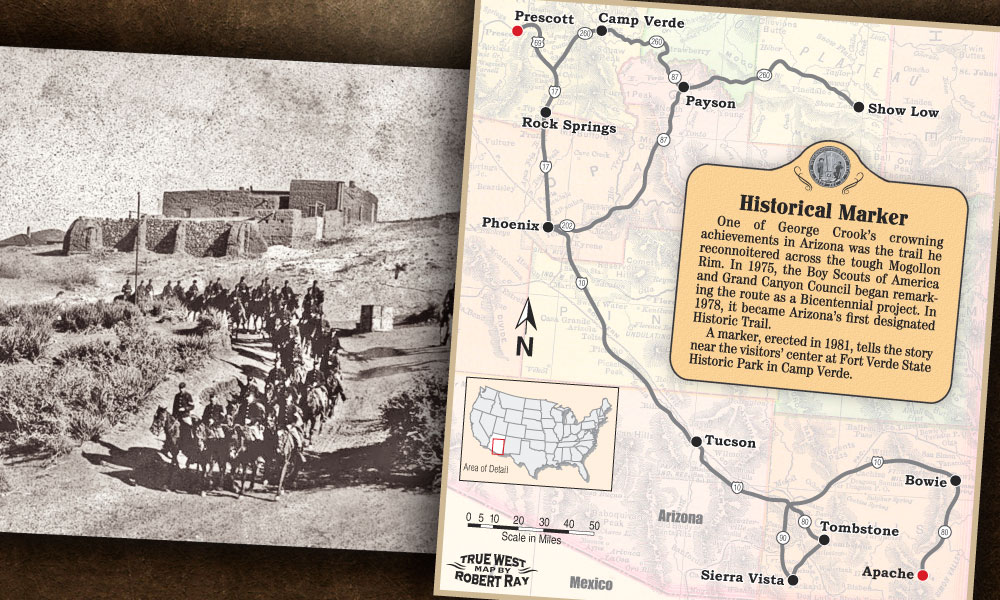

From Camp Verde, follow the Gen. Crook Trail/Road to Show Low. Crook had set out from Fort Apache in August 1871, arriving at Fort Whipple in early September. He called the trail along the Mogollon Rim “a delusion.”

“The trail, at best dim, soon ran out, and the summit was in places very broad and in places cut up by ridges and cross canyons,” Crook wrote. “Not being able at times to tell the main summit from some of the minor ones that ran off to the east, principally, we experienced much difficulty in finding our way.”

In the spring of 1872, Crook ordered a better trail blazed. In September 1874, the first supply train left Fort Whipple on the new road. Traveling with her Army officer husband in an ambulance, Martha Summerhayes did not care much for the road. “For miles and miles, the so-called road was nothing but a clearing, and we were pitched and jerked from side to side…,” she recalled.

It’s better today—and offers a wonderful driving experience. But pay attention to that road!

Phoenix and Tucson

After a quick stop in Phoenix to soak up the Pioneer Living History (frontier experience), Heard (Indian art/culture) and the amazing Musical Instrument (worldwide, including Indian tribes) museums, head south to Tucson for a couple of excellent stops maintained by the Arizona Historical Society: the society’s museum on Second Street and the Fort Lowell Museum, housed in a reconstructed version of the commanding officer’s quarters.

The fort was first established in 1866 in the town but moved in 1873 to a spot south of Rillito Creek. Tucson wanted Crook to set up command here. But Crook preferred Whipple—but not because hot Tucson had been described as “a city of mud-boxes, dingy and dilapidated, cracked and baked in a composite of dust and filth…” No, Crook found Whipple to be closer to supplies and communication with California. Besides, Prescott also had hops.

But had the general sampled the prickly pear margarita at Tanque Verde, one of Tucson’s outstanding guest ranches, he might have changed his mind.

Yes, Tanque Verde was there. Having moved his family from Sonora to Tucson in 1856, Don Emilio Carrillo started ranching here in 1868. The ranch, which began taking in paying guests in 1928, puts a lot of emphasis on history, plus nature, horsemanship, comfort, good

eats and fun.

Second time around

In July 1882, Crook was ordered back to Arizona after an ugly incident between soldiers, scouts and Apaches at Cibicue Creek in August 1881. Several Apache scouts mutinied when the Army attempted to arrest a medicine man. Eight soldiers were killed, along with the shaman and many Apaches. Three scouts would be court-martialed and hanged at Fort Grant with two others dishonorably discharged and sent to Alcatraz.

But in September, Crook placed his faith in the use of Indian scouts. Catching Apaches, he said, “if done at all must be mainly through their own people.”

Matching wits against Geronimo, and Chato, and Juh, and Nana, and Loco, and Bonito, Crook was mostly successful. Their stories are well-chronicled at the Fort Huachuca Museum on the still-active military post in Sierra Vista, and at the Fort Bowie National Historic Site, a good hike to mostly ruins, a long dusty drive south of Bowie. (Yes, Wyatt Earp-aphiles, a deviation to Tombstone is permitted.)

Geronimo made a career of surrendering to Crook. In 1886, however, after Geronimo fled again after agreeing to surrender, Army General-in-Chief Phil Sheridan had had enough. Snotty messages went back and forth. Crook asked to be relieved. Sheridan happily agreed, replaced him with Brig. Gen. Nelson Miles, and Crook returned to Omaha and the Department of the Platte.

End of the trail

Eventually, Miles had to turn back to Crook’s method and relied on Lt. Charles Gatewood—with two Apache scouts—to induce Geronimo to surrender.

So it was Miles who accepted Geronimo’s surrender at Skeleton Canyon in 1886, and it was the U.S. government that sent the Apaches—including the scouts who had helped end the bloodshed—out of Arizona. That move irritated Crook until March 31, 1890, when he died of heart failure at the age of 61.

In 1886, however, it was Miles being feted as “the hero of the day,” and Crook being reviled.

By whites—not Apaches.

“Crook was our enemy; but though we hated him, we respected him,” recalled Juh’s son, Asa Daklugie. “…Did Miles come within any reasonable distance to confer with Geronimo? He stayed close to Fort Bowie.”

– True West Archives –

Since George Crook loved mules, Johnny D. Boggs often wonders what the general would think of the work of San Carlos Apache-Akimel O’odham artist Douglas Miles (no relation to Nelson). Check out ApacheSkateboards.com.