Working deep in the earth as a miner is a job with many hazards, including poison gases, explosions, collapses, floods and fires to name a few. To miners like James Dunlevy, the risks were just part of the job.

Dunlevy did not dwell on these dangers as he worked in the Yellow Jacket Mine in Gold Hill, Nevada. The mine and sister mine shafts were burrowed more than 1,000 feet into the earth as they extracted silver from the Comstock Lode. Each labyrinth of mining chamber was supported with heavy timbering. In this tinderbox of wood, miners lit their work with candles or lamps, and they used blasting powder to fracture the ore for removal.

On April 6, 1869, a careless miner left a candle burning on a wall of timber some 900 feet deep in the mine, which eventually set fire to supporting timbers. This blaze started a chain reaction of disasters.

Dunlevy, who was working on the 900-foot level, was alerted to the catastrophe when he heard the distinctive crashing of falling rock. Debris filled the tunnels, forcing choking gases and dust into the Yellow Jacket and neighboring Kentuck shafts.

While running along the 900-foot level, Dunlevy spotted a wall of flame. As he raced toward the main shaft, he gave the signal for fire, but the crackling of the burning pine timbers was so loud that his warning shouts were drowned out.

Through the cacophony, he heard the screams of miners on the levels below. Air pouring in through the Kentuck mine acted like a bellows and fanned the conflagration.

The roof collapsed around Dunlevy, and he began to choke on the fumes and dust. He lay on the floor and pulled a heavy overcoat over himself. This act helped save his life. He was the sole survivor of nine miners on the 900-foot level. He slipped into unconsciousness and did not awaken until hours after he had been rescued.

Miners risked their lives to save their coworkers, trying to rescue as many men as possible. They yanked the unconscious Dunlevy from the jaws of death. Later, when a cage filled with rescuers was descending past the 800-foot level, it was rocked by an explosion. The fire quickly spread to another neighboring shaft, the Crown Point Mine.

The morning was filled with stories of heroism and tragedy. Many miners had to be left behind, as the crowded cages were too full to pull them out. Some miners jumped to their deaths rather than suffocate or be burned alive. One man hanging on to a cage had his head and arm removed by jagged timbers.

Fighting the flames took weeks, and 70 miners reportedly perished. Many of the bodies remained in the deep where they had fallen. Dunlevy was saved by his own quick thinking and by his brother miners.

Survival Tip: Getting Down with Fire

In many respects, the Yellow Jacket Mine disaster showed a basic safety principle when dealing with fire within a structure. James Dunlevy would have perished save for his happenstance of being thrown to the ground and pulling a heavy coat over himself.

The hot gases generated by fire rise quickly. These fumes can scorch the lungs in an instant and can cause a person attempting to leave while in an upright position to pass out. The most breathable air in a burning structure is found by the floor. Once the exit path begins filling with hot fumes, you should crawl out of the building as rapidly as possible.

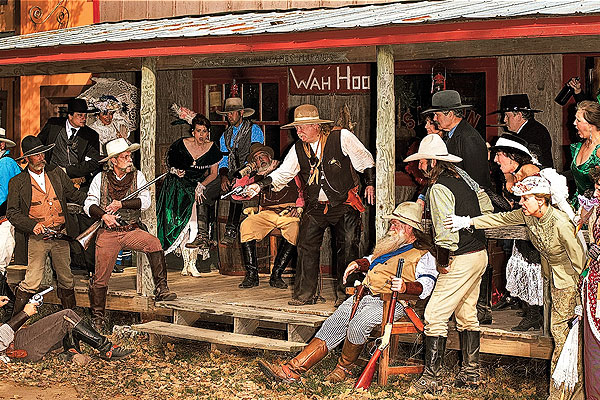

History in Art

By Illustrator Andy Thomas

This miner attempts to hang onto the overcrowded elevator as it returns to the surface. He wears minimal clothing, as the Comstock Lode was the “hottest by far in the world,” with water temperatures reaching 170 degrees Fahrenheit by 1881. To cool himself, a Comstock miner consumed 95 pounds of ice on average daily. He chewed the ice, rubbed it on his body and poured ice water on his head, but he might still pass out from the fetid air. These miners certainly had a glimpse of hell.