– Courtesy Library of Congress –

The Dallas Times Herald newsroom was abuzz that summer of 1985. Practically everyone had a copy of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove.

We knew or at least knew of McMurtry, the Archer City native often seen wearing his “Minor Regional Novelist” sweatshirt. Those of us longing for a career in fiction could only dream of being that kind of minor regional novelist. McMurtry’s Horseman, Pass By (1961), Leaving Cheyenne (1963), The Last Picture Show (1966) and Terms of Endearment (1975) had been adapted as movies, winning 10 Academy Awards with 16 other nominations. But in Lonesome Dove, McMurtry left behind his 20th-century West for an epic, 843-page cattle drive from South Texas to Montana.

Long novels of the West were not unheard of in the mid-1980s—such as James Michener’s Centennial (1974) and Lucia St. Clair Robson’s Ride the Wind (1982)—but the critical and commercial reaction to Lonesome Dove boggled the mind. Holding its own against Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October, John Irving’s The Cider House Rules and Louis L’Amour’s Jubal Sackett, Lonesome Dove sold almost 300,000 copies in hardcover and more than a million when it was released in paperback. In 1986, the novel won the Pulitzer Prize.

My newspaper colleagues told me not to give up on Lonesome Dove. It took some of them 40 pages, even 140 pages, before they “really got into it.” But McMurtry hooked me with the first line: “When Augustus came out on the porch the blue pigs were eating a rattlesnake—not a very big one.” After knocking off work on the sports desk around 1 a.m., I returned home and read the last 180-plus pages, finishing at sunrise, in tears.

What surprised McMurtry was how readers interpreted his novel. As he later wrote, “I thought I had written about a harsh time and some pretty harsh people, but, to the public at large, I had produced something nearer to an idealization….”

– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

The idea for the novel started as a screenplay for The Last Picture Show director Peter Bogdanovich, who wanted to make a period Western starring John Wayne, James Stewart and Henry Fonda. McMurtry’s screenplay, “Streets of Laredo,” never got produced, and after Wayne’s death, McMurtry bought the rights back and began turning the idea into a novel. (Lonesome Dove contains some character names and plot elements from Bandolero!, a 1968 Western starring Stewart and written by James Lee Barrett from a story by Stanley L. Hough.)

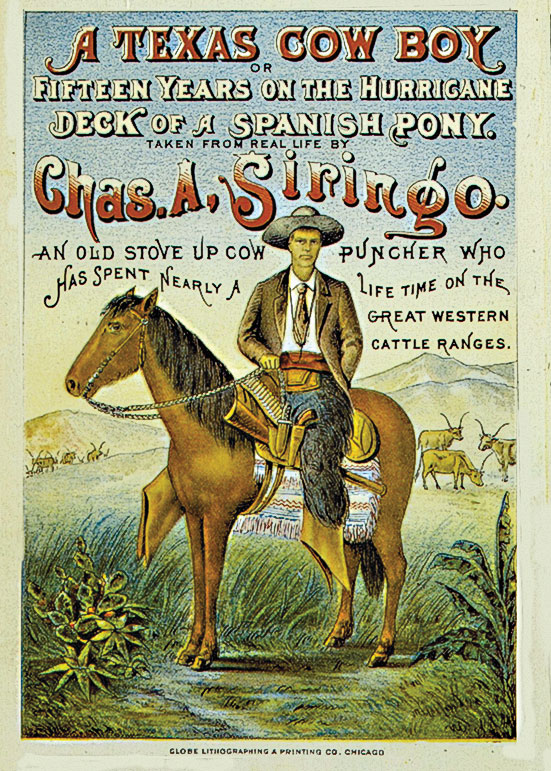

McMurtry borrowed from the 1860s cattle drives of Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving from Texas to New Mexico, Nelson Story’s 1866 drive from Texas to Montana and Andy Adams’s 1903 novel The Log of a Cowboy. He then added strong women characters and mesmerizing prose to create what Los Angeles Times reviewer John Horn called “McMurtry’s loftiest novel, a wondrous work, drowned in love, melancholy, and yet, ultimately, exultant.”

In McMurtry’s story, aging ex-Texas Rangers Woodrow Call and Augustus McCrae head the cattle drive. “McMurtry examines their bond—an unspoken and hardly understood friendship,” the Los Angeles Daily News reviewed. “In western fiction, a like relationship seldom has been more finely crafted.”

The Western film was supposed to be reinvigorated in 1985, but Pale Rider and Silverado never lived up to box-office and critical expectations. The Western TV-film revival would have to wait until Young Guns hit theaters in 1988, raking in roughly $45 million, and Lonesome Dove aired as a four-part miniseries in February 1989, drawing 26 million viewers.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

But McMurtry’s novel helped pave the way for a slew of Western fiction with a literary bent: Gary Matthews’s Heart of the Country, Pete Dexter’s Deadwood and Ralph Beer’s The Blind Corral (all 1986), Robert Flynn’s Wanderer Springs (1987) and Glendon Swarthout’s The Homesman (1988).

Great books, certainly, but Lonesome Dove became the 20th-century classic of the West. Says Austin, Texas-based novelist Stephen Harrigan (The Gates of the Alamo, Remember Ben Clayton): “It was one of those rare books that had everything: a relentlessly fast-moving story with two central characters—Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call—who were not just interesting on the page while you were reading but would reverberate in your memory for decades afterward.”

In 1989, the Dallas Times Herald newsroom was abuzz again before the miniseries premiered on CBS. Robert Duvall would be perfect as Call, but Gus? Tommy Lee Jones is too young to play Call! Robert Urich and Ricky Schroder—they can’t act! Will screenwriter William D. Wittliff butcher McMurtry’s story? Can director Simon Wincer pull this off?

We didn’t know what Michigan-based author Loren D. Estleman, no slouch in the literary Western department (1984’s This Old Bill, 1987’s Bloody Season), knew.

TV Guide had sent Estleman to the Lonesome Dove set for a story.

– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

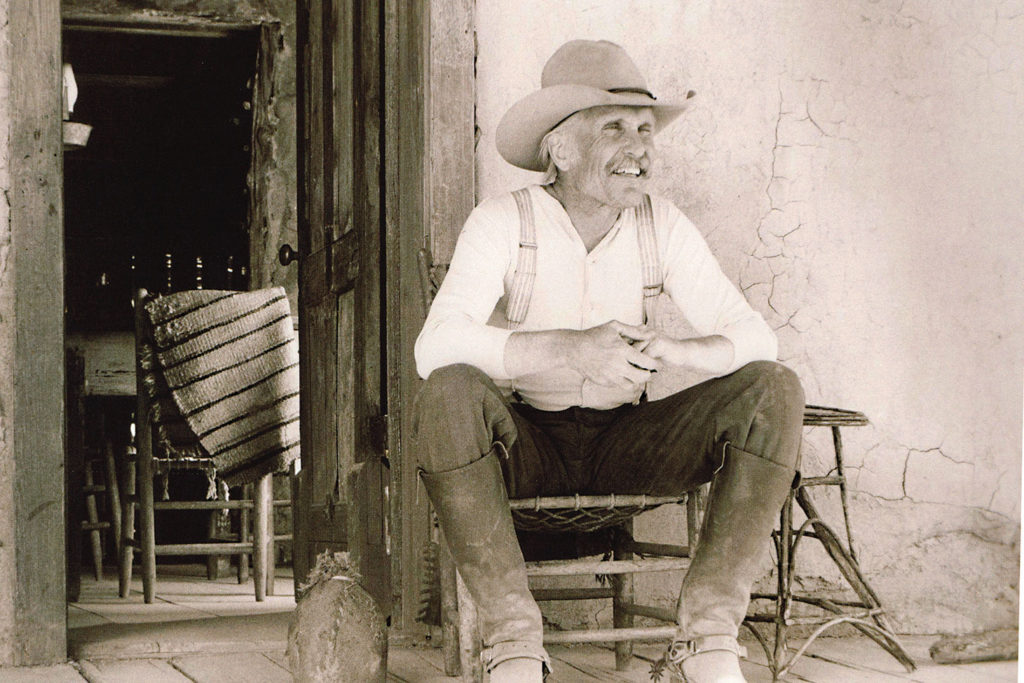

“From the moment [Danny] Glover rode past me the first day, wearing Deets’s checkered pants, I knew the miniseries was going to be an instant classic,” Estleman recalls.

Adds Harrigan, who also spent time on the set: “You could sense the weight of responsibility that the actors and crew were feeling. They knew Larry McMurtry’s novel was beloved, and that they would never be forgiven for ruining it.”

Estleman interviewed Glover while the actor was being treated for cuts and scratches on his legs. “He said he kept forgetting to put on protective long johns,” Estleman recalls. When Estleman asked Glover how a modern actor could identify with an 1870s character, Glover replied: “The moment I’m on a horse, I’m there.”

But it was Duvall who gave Estleman the quote he wanted to use for the title of the TV Guide story: “It’s going to be the Western Godfather.”

The editors didn’t see that and buried the story inside as part of a sweeps-week feature.

Nominated for 19 Emmys and winning seven, the Lonesome Dove miniseries became as revered as McMurtry’s novel, leading Dallas Times Herald colleague Frank Wooten to quip: “Next will come the TV series—with Jack Klugman as Gus.” A short-lived series, titled Lonesome Dove: The Series (1994-1995) and Lonesome Dove: The Outlaw Years (1995-1996), was quickly forgotten. Klugman couldn’t have hurt its reputation even if he had been cast.

– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

But a four-part sequel, Return to Lonesome Dove, written by John Wilder and directed by Mike Robe, aired in 1993. McMurtry had nothing to do with the sequel (and says he never watched all of the original), and got his revenge with his own sequel, Streets of Laredo, that came out the same year and killed off the character of Newt, played by Schroder in the original miniseries and sequel. Two other novels by McMurtry in the series, Dead Man’s Walk (1995) and Comanche Moon (1997), also became miniseries. None recaptured the magic of the original novel or miniseries, which, Skip Hollandsworth pointed out for Texas Monthly in 2016, “were arguably more influential in shaping Americans’ vision of the Old West than the movies of

John Ford.”

Decades have not diminished the impact of McMurtry’s original novel or the miniseries.

“Part of the magic of both the book and the miniseries is that Gus and Call are completely original but also archetypal, as perfect a pairing of human opposites as Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson or Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock,” Harrigan says.

The novel and miniseries continue to influence writers—and even the families of writers. Says Austin-based novelist Elizabeth Crook (Promised Lands, The Which Way Tree):

“I didn’t finish reading the book because I got wind of the fact Gus was going to die, and I decided not to go through it. But I went through it in the movie, time and again, and so did my kids—Gus’s death, Jake Spoon’s death, Blue Duck’s.

“My son was 14 when I walked into his room and found the words Jake Spoon said before his hanging scrawled across an entire wall in huge letters: ‘I’d damn sight rather be hung by my friends than by a bunch of strangers.’

“It was Blue Duck’s death that impressed my daughter. She was about five when she watched him hurl himself from the jail window, and asked, pensively, ‘Mama, did Blue Duck fail his life?’

“It takes a great, timeless story to make a family sit and ponder the notion of whether a person can fail their life.”

– Courtesy CBS –

Johnny D. Boggs also binge-watched the Lonesome Dove miniseries in 1989, starting after knocking off work at the Dallas Times Herald and finishing, in tears, at dawn.