Paul Hedren has led two lives. About the days working as a National Park Service historian and superintendent, he admits lucking into some remarkable experiences, including the arrival and dedication of Golden Spike National Historic Site’s fully operational steam locomotives in 1979, and the reconstruction of Fort Union Trading Post in North Dakota in the mid-1980s. Since retiring in 2007, he has devoted his energies to history, writing of the 1870s in the northern plains. When not prowling the Black Hills or Sioux war landscapes, he and his wife, Connie, are comfortably at home in Omaha, Nebraska.

Growing up in Minnesota birthed a love of Lake Superior agates, Indian arrowheads, the Dakota War of 1862, Grain Belt beer and Minnesota Twins baseball.

Winters….whether in Minnesota, Montana’s Big Hole or Williston, North Dakota, are formidable, and you love or hate `em. I mostly suffered them, and in January always preferred Arizona. Still do.

My parents introduced me to the American West. We were hearty camper travelers who prowled most of the Western national parks from Yellowstone and Glacier to Yosemite and the Grand Canyon, and all points and parks between.

My first history mentor was a devoted field historian and interpreter, B. William “Bill” Henry, Jr. He was the man who hired me into the National Park Service.

The first national park I visited was Badlands National Monument about 1954, where my dad posed me with an ancient-looking Indian—who was almost certainly Dewey Beard—at his tipi set up behind the park visitor center.

My first posting as a park ranger was at Fort Laramie National Historic Site in 1971. It was magical, whether wearing a flat-brimmed ranger hat this day or an old soldier uniform the next, and this in the steep of history spanning the fur trade, overland trail, pony express, Indian treaties, Spotted Tail, Crook and all those marvelous old buildings.

My most remote posting was the Big Hole National Battlefield in southwestern Montana, a somber Nez Perce War site by day but also featuring a glorious blue ribbon trout stream that some of us overworked in the afterhours.

Marriage and family are ultimately all that count, though pity my endlessly suffering girls, tormented as they were (or so they still claim) by seemingly nonstop visits to museums, forts and battlefields.

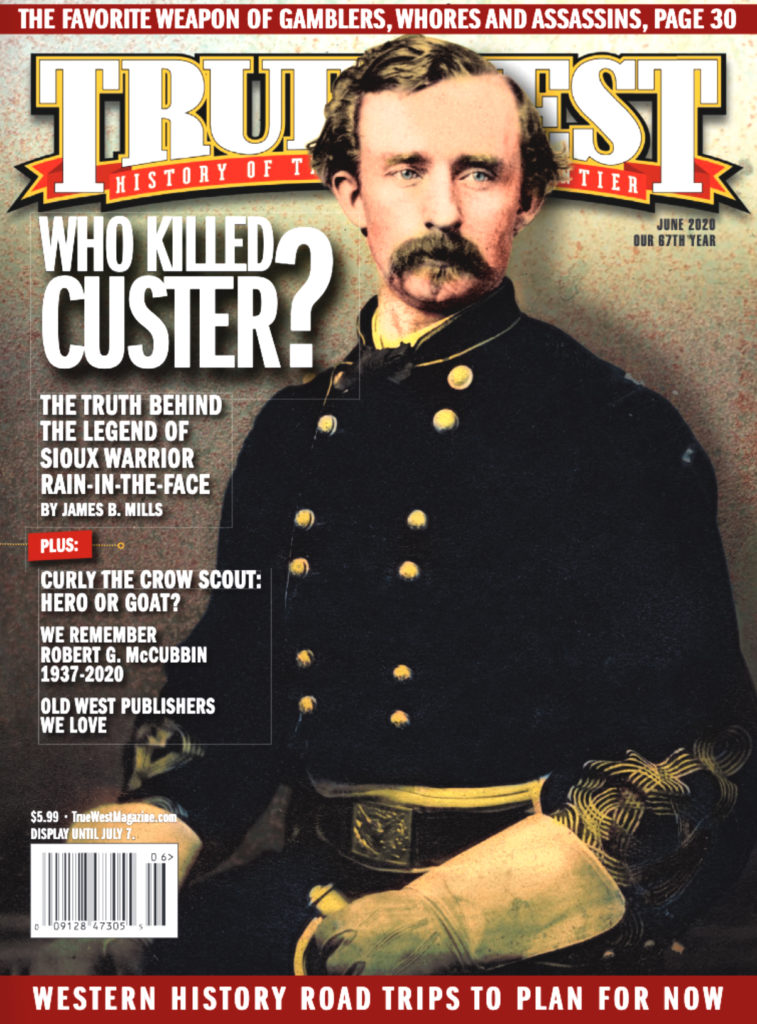

The first time I visited Little Bighorn Battlefield was on a trip to Yellowstone in about 1964. As a kid I was an obsessed Custer buff and the stop was mesmerizing almost to tears.

If I had a moment with Crazy Horse, I’d plead with him to go to that meeting with Crook, and that meeting in Washington with the President. And I’d caution him about trusting all those interpreters hovering about, especially Grouard.

If I went fly-fishing with Gen. George Crook, I’d nag the ever-quiet one for his version of the turnaround at the Rosebud Narrows in the late afternoon of June 17. Did he truly feel so helpless without his Crows and Shoshones, even when leading a thousand tested Regulars?

Sitting Bull was easily the greatest of the Lakota traditionalists, a charismatic spiritualist who clung to glories of the chase to the very day of his death.

The Battle of Little Bighorn sealed the traditionalist’s fate. We know this, but when did they?

My next book presents the field dispatches of John Finerty, reporting Crook’s summer campaign against the Sioux for the

Chicago Times. Too many of us have assumed that Finerty so fully exhausted those letters and telegrams when preparing his 1890 book War-Path and Bivouac as to make the original pen work superfluous. Well, not so, and not even close.

What has history taught me? I live in the world of Custer, Crook, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. History tells me that there is much yet to explore in what some consider to be a timeworn tale. New sources, keen insights, and fresh connections abound. My horizon keeps expanding.