Seven feet tall. Ten inches square. Eight hundred pounds. Once, 720 of them. Every half-mile from Minnesota to Montana. Standing since 1891 or 1892. The only stone sentinel of its kind in the nation.

Seven feet tall. Ten inches square. Eight hundred pounds. Once, 720 of them. Every half-mile from Minnesota to Montana. Standing since 1891 or 1892. The only stone sentinel of its kind in the nation.

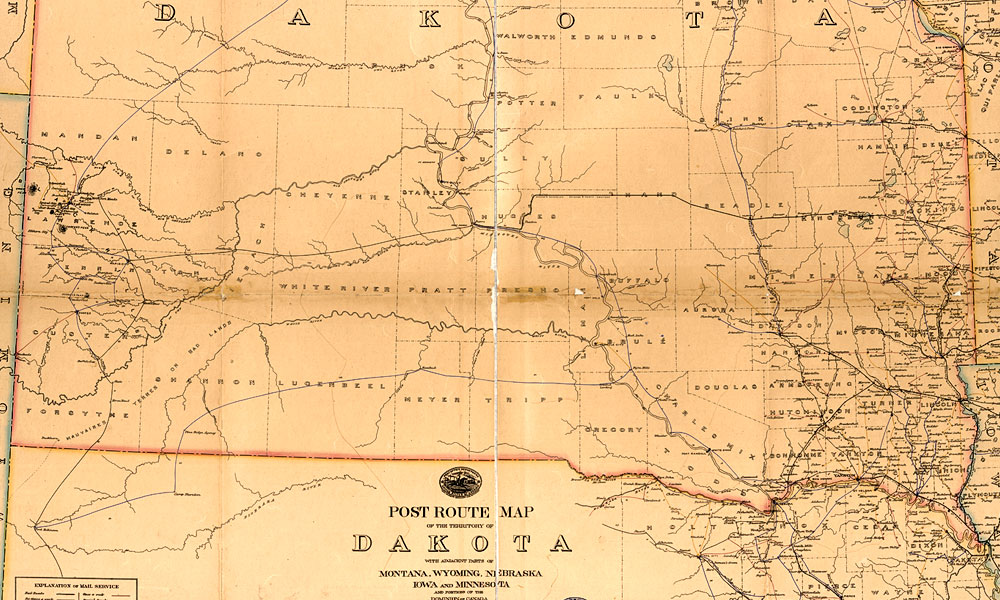

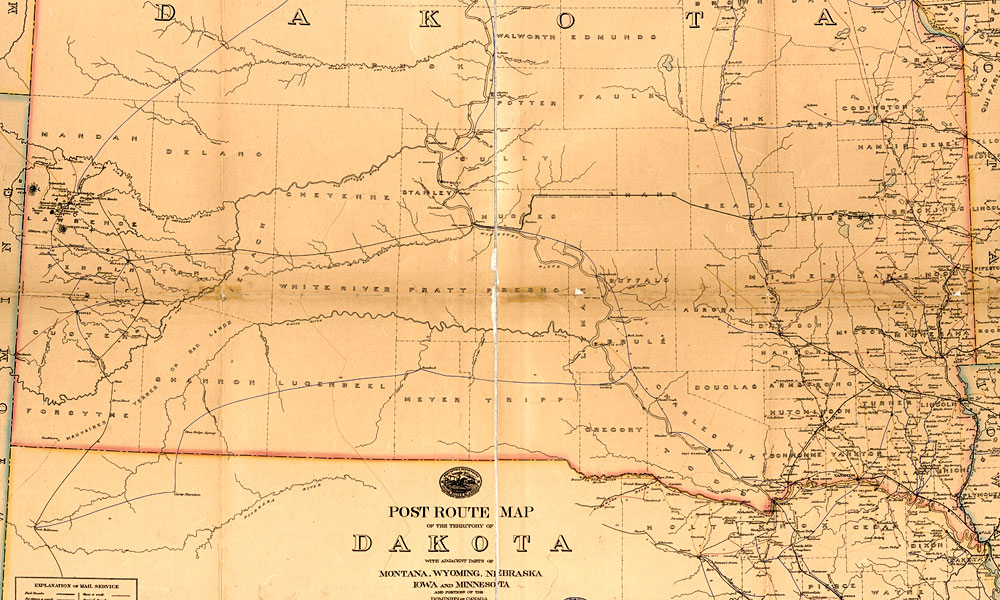

That’s the legacy of the red quartzite boundary markers the federal government installed after Dakota Territory was split, in 1889, into the 39th and 40th states of North Dakota and South Dakota.

The federal government wasn’t being heavy-handed in determining the boundary; they were “reluctantly” settling a long-standing state dispute.

“It was a difference of 10 miles,” notes Rick Snyder, of rural Fairmount, North Dakota. “Neither side wanted to give up those miles.”

Snyder grew up with the monoliths as common as the cornfields. He expected they’d always be there, since quartzite is second in hardness to diamonds. But over the years, he noticed them tipping, tilting and disappearing.

Some were claimed as trophies—demanding quite an effort, since the heavy monuments were planted 3.5 feet deep—and others were discarded by road crews or farmers who found them in the way. One near Snyder’s farm ended up buried when a new road came in, and years later, a grader scraped the top of the marker.

That discovery propelled Snyder to do something. He is joined by about 20 others in a project to restore the markers to their unique place in history as the only boundary of its kind in the nation.

Snyder never buckled as one “no” after another came for three years. The Bureau of Land Management told him not to touch them and sent him to get state approval. But the historical society and attorney general in North Dakota couldn’t be bothered.

Snyder finally got South Dakota’s historical society and attorney general to give him permission to straighten the existing markers and search for those long gone. He used that letter to prod the same approval from North Dakota, and, in 2015, everybody got busy…on their own dime and in their own time.

This proved to be a tenacious effort, just like the original surveying and planting of the markers, which were hand carved at their quarry in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and delivered by rail and horse and wagon. Each mile marker—with “N.D.” carved on one side and “S.D.” on the other—includes the distance from the Minnesota border.

A complete survey across the 360.57-mile border hasn’t been completed yet, but Snyder estimates less than half the markers are still in place. He and his friends are talking with others farther west, “and they’re getting ready to take the baton,” he says.

“There’s a real sense of accomplishment that we’re actually rescuing them,” adds Snyder, with earned pride in his voice.

Jana Bommersbach has earned recognition as Arizona’s Journalist of the Year and won an Emmy and two Lifetime Achievement Awards. She cowrote the Emmy-winning Outrageous Arizona and has written two true crime books, a children’s book and the historical novel Cattle Kate.