— Courtesy John Boessenecker —

Frank Hamer rested his muscular frame against the trunk of a hackberry tree. He levered a round into the chamber of his Winchester Model 1894 saddle ring carbine, then squinted down the rear sight. Drawing a long breath, he slowly squeezed the trigger and the hammer dropped. The next instant would mark the beginning of his career as the deadliest Texas Ranger of the 20th century.

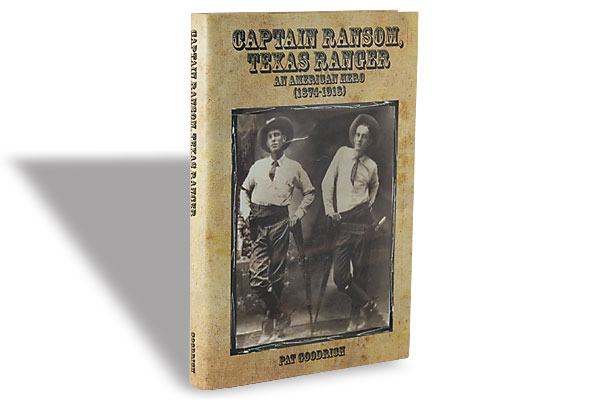

— Family Home photo courtesy Texas Ranger Hall of Fame, Waco, TX —

Hamer (pronounced “Haymer”) was born in the Texas Hill Country in 1884. The son of a blacksmith, Frank spent long hours toiling with sledgehammer and anvil in his father’s shop. He grew into a powerful six-foot-two-inch youth, all muscle and gristle. Hamer had no formal schooling after the sixth grade. As he once said, “The only education I got was on the hurricane end of a Mexican pony.” He lived much of his early life outdoors and became an expert rider, rifleman, hunter and tracker. Hamer drifted to the Pecos River country in west Texas and rode the ranges as a cowpuncher. In 1905, as a volunteer posseman, he tracked down and captured several horse thieves. The sheriff of Pecos County was so impressed that he recommended young Hamer as a Texas Ranger.

In April 1906 Frank enlisted in Company C of the State Ranger Force. Then, Rangers were rarely called “Texas Rangers,” for everyone connected with them was in Texas, and adding the state’s name was redundant. They were merely “Rangers” or “State Rangers.” Hamer’s commander was Capt. John H. Rogers, famed as one of the “four great captains” of that era. Rogers did not look like a Western lawman. Portly, bespectacled, gentlemanly and deeply religious, he was a crack detective and a deadly opponent in a gunfight. He had been a Ranger since the age of eighteen and had killed several desperadoes in hair-raising gun battles. Rogers had twice been wounded in the line of duty, leaving one arm permanently injured. He carried a special rifle with a curved stock to compensate for his crippled limb. Frank Hamer idolized his captain, and ever after sought to emulate him. Captain Rogers became the most important influence in Hamer’s professional life.

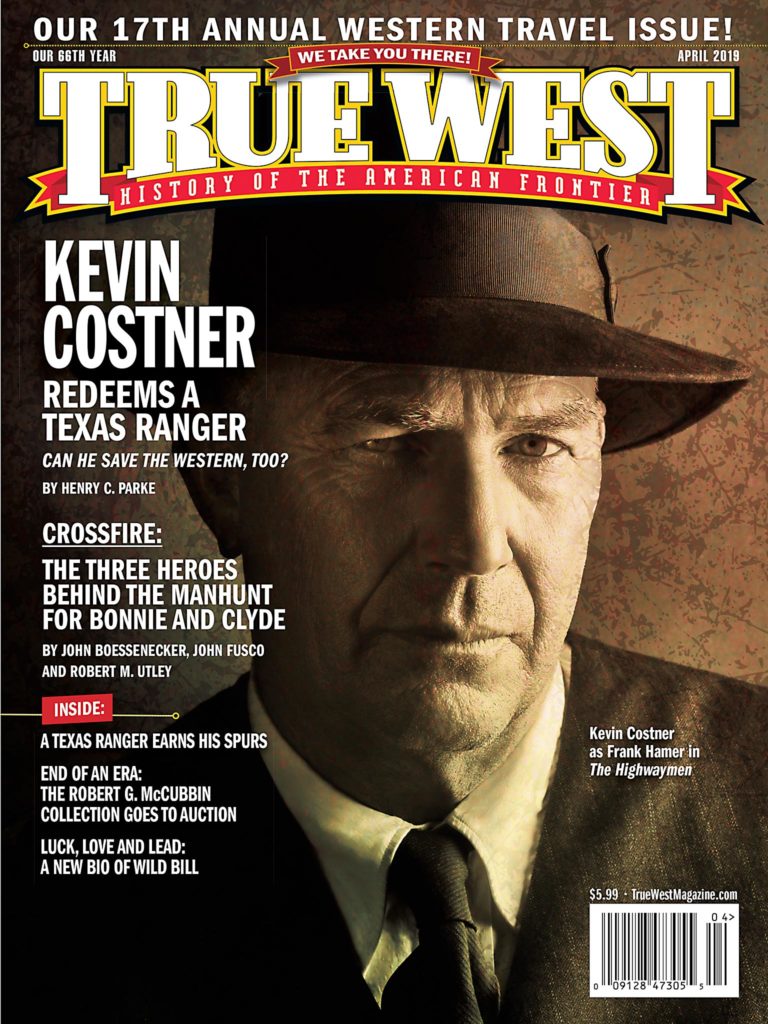

— True West Archives —

The Rangers served not only as a border protection force, riding the Rio Grande in search of outlaws, smugglers and cattle thieves, but they also assisted local officers. Because lawmen were few, and levels of crime and violence were high, the Rangers rode from one hot spot to another, augmenting local police and sheriffs. During Hamer’s first year as a Ranger, he acquired more experience than many modern law officers get in a decade. He rode several thousand miles throughout the border region and the Big Bend, obtaining intimate knowledge of the country and its people. He learned to conduct surveillance, to work undercover and to investigate myriad crimes. He arrested seven men for murder. And he took part in an exploit in Del Rio that folks would talk about for more than a hundred years.

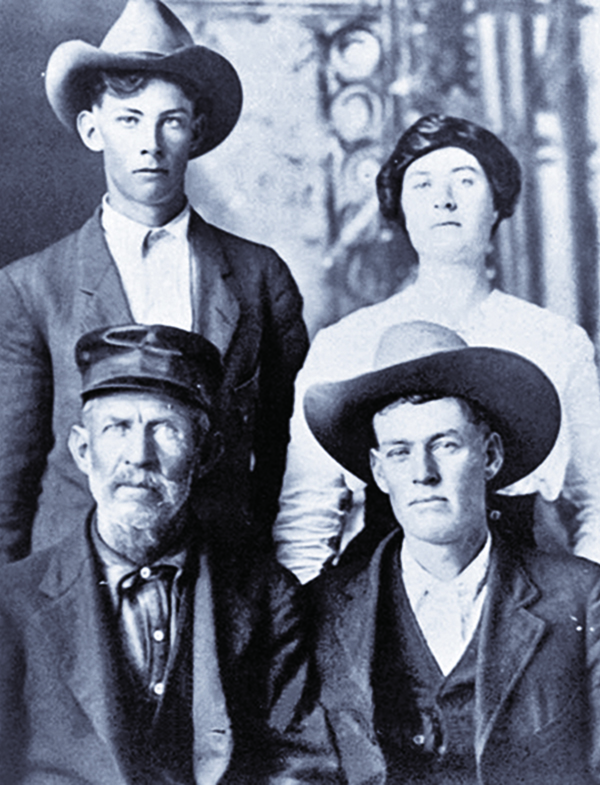

— Photo Courtesy John Boessenecker —

Del Rio, then a dusty border town of 2,000 residents, is situated on the Rio Grande, midway between Laredo and the Big Bend. On November 30, 1906, Captain Rogers received word that a wealthy sheepman, Blake Cauthorn, had disappeared. He began an investigation, and quickly found that Cauthorn had been at the bank in Del Rio, where he paid a stranger, Ed Putnam, $4,500 for a flock of sheep. Putnam had last been seen headed out of town in a livery rig, which was found abandoned 12 miles north of Del Rio. Rogers, with Rangers Hamer and Robert M. “Duke” Hudson and County Sheriff John Robinson, spent the night in a vain manhunt for Putnam. In the morning they got word that Cauthorn had been found in his buggy, shot to death. At about the same time, the Rangers learned that another stockman, John Ralston, who had also engaged in a sheep deal with Ed Putnam, had vanished.

The town was gripped in a fever of excitement, with citizens convinced that Cauthorn and Ralston had been robbed and murdered by Mexican bandits. The Rangers paid no attention to the rumors, and kept up their hunt for Putnam. Rogers inspected Cauthorn’s body, then concluded that Putnam might have circled back to Del Rio to board a train for escape. As the lawmen watched all the outbound trains, Sheriff Robinson got a tip that Putnam was holed up in a bordello operated by Glass Sharp, situated near the railroad tracks on the outskirts of town. The sheriff and his deputies, along with Rogers, Hamer and Hudson, climbed into a pair of hacks and rushed to the Sharp house. It was six p.m., December 1, 1906.

— True West Archives —

Sheriff Robinson placed seven men in the front of the Sharp bordello, while Rogers, Hamer, Hudson and another posseman covered the rear. The sheriff called for the women inside the brothel to come out, and they did so. Then he yelled to Putnam that he knew he was inside. As Rogers later explained, “At first one of the women denied that he was there. Afterwards, they admitted that he was inside and they carried him word from Sheriff Robinson to come out and surrender.” The lawmen allowed Sharp’s daughter, Georgia, to reenter the house and talk with Putnam.

“He won’t come out,” she told the officers. “He’s got a funny look in his eyes and says he won’t give up.”

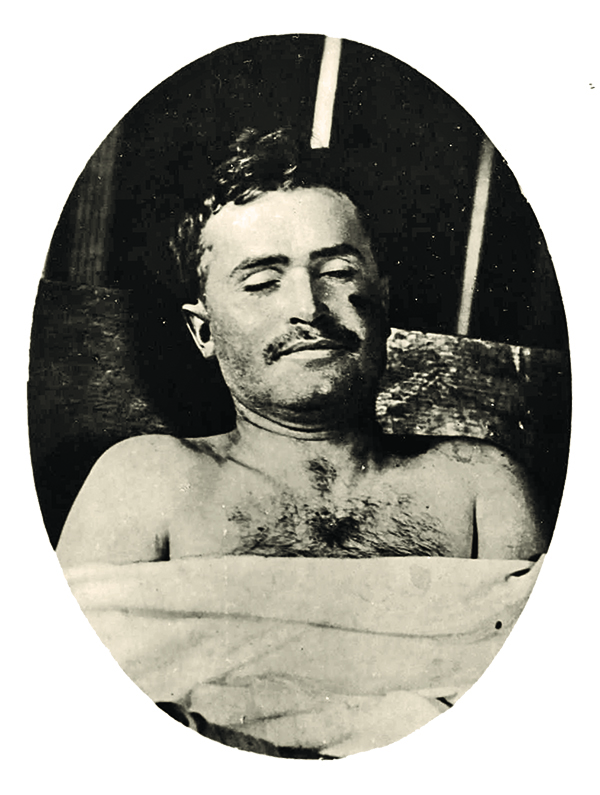

Half an hour passed and Sheriff Robinson lost patience. By this time a crowd of more than a hundred citizens had gathered, some of them armed, and he feared mob violence. Robinson ordered his possemen to open fire on the house. Hamer, crouched behind a hackberry tree at the rear of the house, held his fire. The other officers unleashed a barrage of 30 or 40 shots through the wood walls. In a display of the steady diligence and calm that would mark his later career, Frank continued to hold his fire, while carefully watching the rear windows. Several times he saw a curtain rustle. Then he spotted a pistol barrel poking through the curtain. Hamer took dead aim at the six-gun barrel and squeezed his trigger. The Winchester carbine roared and the heavy bullet tore through the curtain and ripped into the stooping Putnam. It slammed into the killer’s face, just under his left eye, ranged downward and shattered his jaw, then entered his neck, cutting the jugular vein, passed out of the neck, plowed into his left shoulder and exited through his left arm. Putnam crumpled to the floor, dead.

— Courtesy True West Archives —

The possemen heard a loud thud as Putnam fell, but they could not see inside the house. Captain Rogers said later, “However, not knowing whether he was dead, wounded or feigning to be dead, the house was not entered for a time and our party reloaded and fired many times after this until, perhaps, something like two hundred rounds had been fired, when the house was entered and Putnam found to be dead having received one fatal shot.” Putnam clutched a six-gun in his dead hand. Captain Rogers took three guns from his body: a .32 caliber Colt Single Action Army revolver, a .32 caliber Winchester rifle and a newfangled German Luger automatic pistol. The killer’s pockets held 300 cartridges and $3,500 in cash. The walls of the house had been shredded by 500 bullets. As an eyewitness said, “The furniture in the Sharp home was completely wrecked, even the stove legs being shot off.”

The next day John Ralston’s dead body was found north of town where Putnam had dumped it. Putnam had robbed and killed both victims. The noted Noah H. Rose, then a Del Rio photographer, had been a witness to the deadly shootout. He took a photo of the dead Putnam and invited Captain Rogers and his men come to his studio and to sit for commemorative pictures. Rose shot four images of the Rangers. Two were group images, with Rogers seated, holding Ed Putnam’s Luger pistol. Next to him were Hamer, Duke Hudson and an unidentified friend, with their rifles displayed prominently. Then Rose had Hamer and Hudson take off their coats, so their six-shooters and cartridge belts showed, and photographed them both standing and kneeling with their rifles in hand. Those photographs have become iconic in Texas Ranger history and lore.

— Courtesy The Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project, Library of Congress —

Captain Rogers presented Frank Hamer with Putnam’s Colt revolver, saying that since this was his “first gunfight as a Ranger he thought he should have a memento of the occasion.” Hamer’s commanding officer was greatly impressed with Frank’s coolness and deadly marksmanship. In the years to follow, Frank Hamer would eventually become the most famous lawman in the Southwest, noted for his skill in investigating murders and protecting prisoners from lynch mobs. He engaged in 52 gun battles, and killed, or participated in killing, at least 21 desperadoes in the line of duty. And that all took place long before he got on the trail of Bonnie and Clyde.

Western historian John Boessnecker adapted this story from Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde.