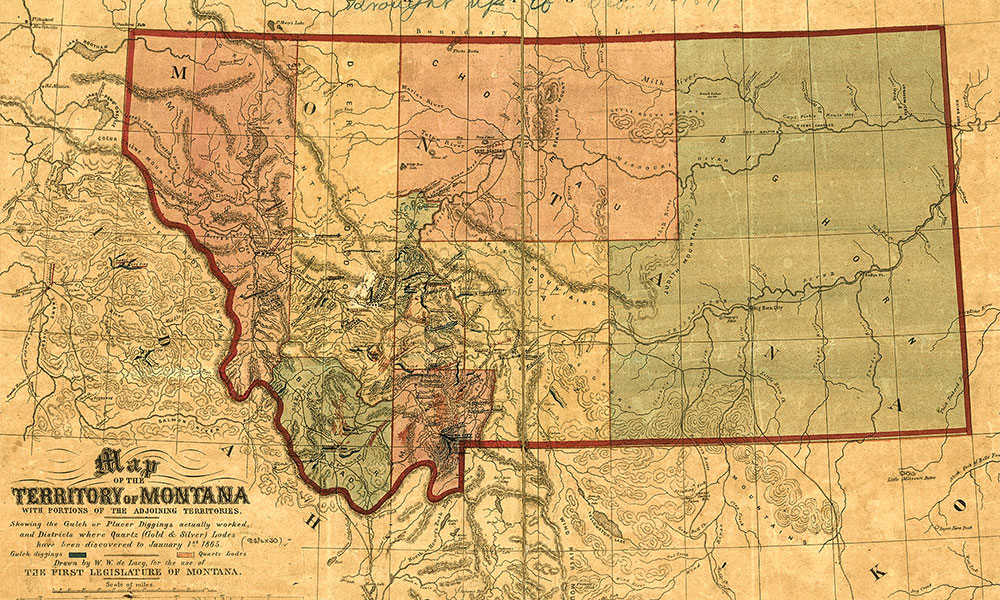

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

Most every Sunday afternoon as I was growing up, my father would load us into the car and off we’d go on a family day-adventure to “discover new sights.” Perhaps these jaunts, and the fact that I have a pioneer-gypsy soul, make exploring the trails of the West one of my passions. Living in South-Central Montana, the tales of the Lewis and Clark expedition have always ignited my imagination, especially as our ranch borders the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River, named by William Clark in July 1806.

When the Corps of Discovery camped at the confluence of the Yellowstone and the Missouri rivers the night of April 26, 1805, it was their first step into what is now Montana. Within the next two months, the expedition would travel along the twisting Missouri River, headed west towards the Pacific Ocean. On their return trek homeward, when they again reached Montana, the Corps split up, each smaller group exploring different waterways and terrains. Today, many of these places can be visited and are identified by historical markers. Exhibits dedicated to the Corps of Discovery can be found in several museums and interpretative centers along their route.

Recently I took a loop of adventure to explore part of the Lewis and Clark Trail. I started in Montana’s capital city, Helena, which was not named Helena until the discovery of gold in 1864, and became the capital in 1875. Nestled downtown, near the Capitol building, is the award-winning Montana Historical Society Museum. Western artists, including Montana’s own Charles Russell, are featured, their outstanding artwork displayed in several halls. Here you can find intriguing historical, archaeological and geological exhibits that pertain to Montana, as well as regional native people artifacts. The Lewis and Clark exhibit includes a time line about their trek in Montana and their impact on the state.

On to Great Falls

–Courtesy Visit Montana –

My next destination took me north to the city of Great Falls, where, in 1805, the Corps of Discovery found themselves surrounded by high steep riverbanks and deep-cut ravines, through which a series of five waterfalls roared. It took over a month of arduous preparation before they could circumvent the falls and continue their trek westward. The explorers knew there was but a short time before winter would arrive, and with the help of Sacajawea, they wanted to locate the Shoshone Indians as quickly as possible. Today, although two dams have altered the flow and appearance of the Missouri River, you can still see the splendor and wonder of what Lewis called, “…the Grandest sight, the Great Falls…”

Situated nearby in Giant Springs Heritage State Park, the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center. This state-of-the-art center is home to extensive archives and the Lewis and Clark Heritage Foundation. Displays share the stories of the Corps’ interaction with the native Indian cultures, the interpreter Charbonneau and his wife Sacajawea, her son Baptist (nicknamed “Pomp”) and Lewis’s Newfoundland hound, Seaman. If you are adventurous, you can even try your luck at pulling a boat against the rushing current of the Missouri River. Open Memorial Day through September, the site also includes living history grounds and several overlooks. In June, an annual Lewis and Clark Festival features historical re-enactments, native dancing and fun events. (For more information, consult LewisAndClarkFoundation.org.)

Continuing northward along Highway 87, I entered a landscape filled with badlands and a beautiful flowing expanse of the Missouri River. Designated the Upper Missouri Wild & Scenic River, it is home to Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument. The monument is administered by the BLM and covers about 377,000 acres of public land, known for its spectacular historic, scientific and cultural variety. Lewis and Clark made note of the area and its wide range of animals in their diaries: “...it [the landscape] is abundant with wildlife…elk, big horn sheep, sage grouse and the prairie dog…a new to science specimen.” This scenery has remained much the same as when Lewis and Clark traveled its rugged terrain. It is along this section of the river that the endangered pallid sturgeon spawns and where one of the country’s last six remaining paddlefish populations exists. Here, too, thrive the few remaining fully functioning cottonwood forests, a seed source for cottonwoods throughout the flood plains of the Missouri River. This unique ecosystem includes a 149-mile long drive where glaciers and volcanic activity, along with erosion, have shaped the landscape. Because roads are limited and accessibility in some areas is only by foot, I recommend stopping at the Missouri Breaks Interpretive Center at the monument. The center offers maps, and information about area points of interest and activities.

Fort Benton

— Courtesy Fort Benton Museum —

A few miles out of the badlands of the Upper Missouri Breaks is the historic town of Fort Benton. Located on the banks of the Missouri River, Fort Benton is one of the oldest towns in the state and often called the Birthplace of Montana. It was established by the American Fur Company in 1846, when steamboats docked along the nearby levee, their decks filled with freight. These trade goods were then carried via ox train to destinations west to help meet the expanding demand for needed items. I visited the museum at Old Fort Park and took a tour of the trade store, which is filled with buffalo robes, beads, blankets and other period trade goods. There is a blacksmith and carpenter’s shop, as well as a fur-traders’ warehouse, telling the history of one of the most important robe trading posts on the Upper Missouri River.

The confluence of the Judith and Missouri rivers is only a few miles from Fort Benton and long before Lewis and Clark explored here, several Native tribes inhabited it. The Blackfeet, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, Crow, Cree and Plains Ojibwa all used these lands. It was the setting for several important peace councils in 1846 and 1855, and near here the Nez Perce crossed, trying to escape the Army on their way to Canada in 1877. Just north, near what today is Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, Chief Joseph and his followers surrendered at Bear Paw, now a National Battlefield Historical Park.

North of Fort Benton, Lewis and Clark camped on a bluff overlooking the Marias and Missouri rivers, scouting the area for the correct direction they needed to travel westward on the Missouri. Today we know it as Decision Point, where the Corps made the debated choice between following the clear cold river, which we now know was the Missouri, or a more inviting calmer muddy one. If you follow the interpretative signs up the short hill, you can overlook the place where the Corps chose the correct river channel in June 1805.

Missouri River Country

Traveling the pristine landscape of the Missouri River country without using a boat takes you off the Lewis and Clark Trail, but I headed north to explore along Highway 2. I passed through the Fort Belknap Reservation, established in 1888 to contain the surviving members of the Gros Ventre and Assiniboine nations, who, before siding with the U.S. Army against the Blackfeet, were one of the major powers of the northern Plains. Each July the town hosts the annual Milk River Indian Days, featuring athletic contests, a festival and native dancers.

Heading east, the rolling grasslands and open spaces near the town of Malta are much the way Lewis and Clark found them in 1805. It is known as Montana’s Heart of Dinosaur Country and some of the world’s most significant dinosaurs ever discovered were unearthed near here. Continuing east, I discovered the historic town of Glasgow, established in the late 1800s by the Great Northern Railroad. Hundreds of miles of rail across this region provided transport of cattle and sheep, bringing land barons staking their claims to huge parcels of land. The Valley County Pioneer Museum is a great stop, featuring local fossils, Indian artifacts, railroad, early business and wildlife collections.

Only 24 miles south, on Highway 24, is Fort Peck Dam Interpretative Center. With free admission, visitors can view a life-size, fleshed-out model of Peck’s Rex, the Tyrannosaurus Rex discovered 20 miles southeast of Fort Peck in 1997, along with other regional paleontology displays. It is also home to two of the largest aquariums in Montana, displaying the fish of Fort Peck Lake and the Missouri River. During the summer, interpretive programs and nature walks along the three-mile trail are offered.

Continuing south, I made my way to Miles City, Montana, a town steeped in Western history. Lewis and Clark traveled past here on their homeward journey east along the Yellowstone River. Known once as the horse-trading and livestock center of the country, the world-famous Miles City Bucking Horse Sale is an annual summer event for rodeo stock buyers and breeders. It was here in 1895 that Charles Coggshall opened his saddle-making business, creating his now historic Miles City Coggshall Saddle.

Headed west on I-90, I made one last stop on my Lewis and Clark journey at Pompeys Pillar National Monument. It was here, on July 25, 1806, while resting along the Yellowstone River, that William Clark recorded in his diary that the natives had engraved images of animals upon the face of the rocks. He dedicated the site to Sacajawea’s son, Baptist, who the Corps called “Pomp.” Today, visitors can view Clark’s own signature and date carved into that sandstone wall. It is the only remaining on-site physical evidence of the Lewis and Clark expedition…and a fitting conclusion to my own Corps of Discovery adventure.

Quackgrass Sally is a working ranch wife and freelance author in Montana. She writes about the West from her own experiences, having ridden her horse and driven her covered wagon thousands of miles along the Western Historic Trails.