— Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections —

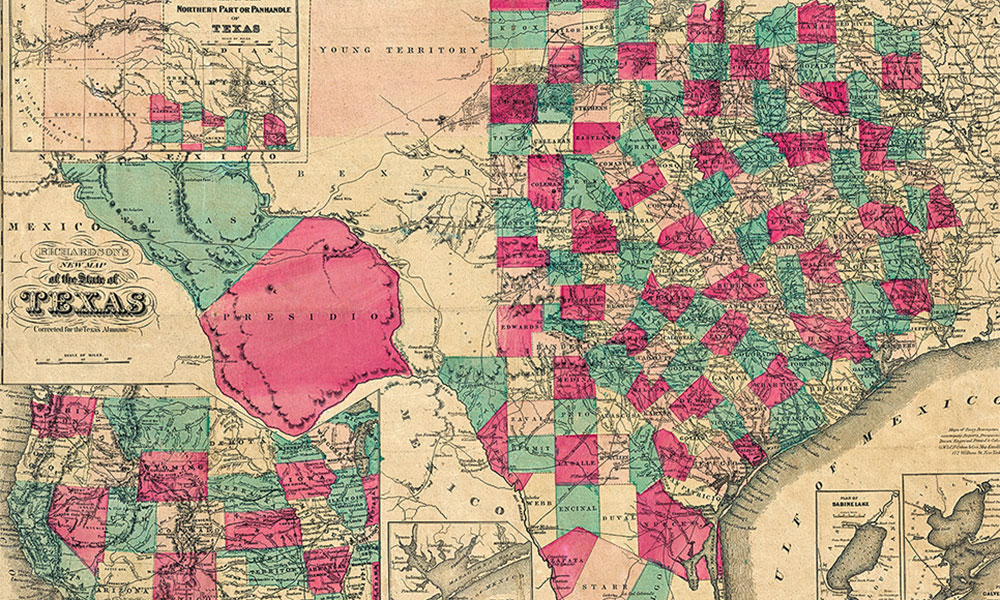

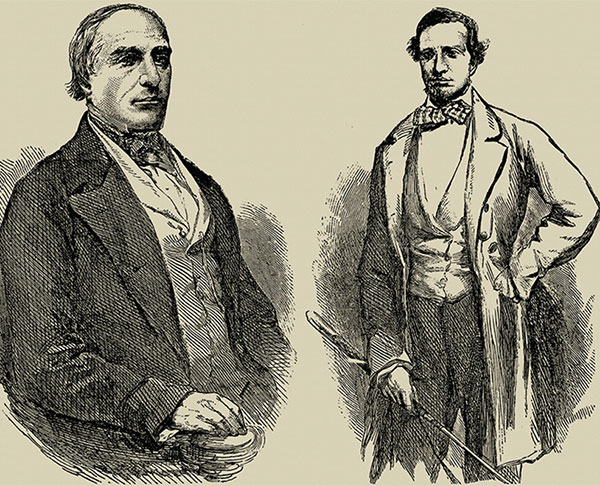

Prior to the Civil War, it was realized that an efficient way to deliver the mail and passengers across the country was needed. In 1857, the U.S. Congress authorized the postmaster to contract for just such a service. In that same year, he sealed an agreement with John Butterfield to provide a stagecoach service that would make the run from Missouri to California by the quickest route that could be found. With that act, the Butterfield Overland Mail Service was born.

John Butterfield was an Englishman who had been raised in New York State. Bringing 37 years of experience in the stagecoach industry, Butterfield quickly set out to acquire the coaches, teams and drivers needed to cross the continent. And, of course, one of the first tasks was to plot out the quickest route to the West Coast. A large portion of the new stagecoach route would be through the state of Texas, with its great variety of geography and other challenges. Although the Butterfield Company slightly changed and modified its routes over the years, we can get a good idea of what the journey was like by looking at some of the known stage stops along the way.

— Image Courtesy True West Archives —

From Missouri, the Butterfield Overland Mail Service ran down through Arkansas and the Indian Territory, entering Texas near the town of Sherman. Sherman sits in the Post Oak Country of northeast Texas, not far from Dallas. Much of that area is black-land farm country even today.

Leaving Sherman, the Butterfield route headed west by southwest through Cooke and Wise counties towards the cowtown of Jacksboro. This region was part of what the old-timers called the Rolling Prairie and is actually part of the southern plains region. From this point on, not only would water be a scarcer commodity, but the stage line would also face the threat of attack from the Comanches who, in the 1850s, were still a force to be reckoned with.

— Image Courtesy True West Archives —

This is probably the reason that the next stop for Butterfield’s stages would be at Fort Belknap, some 37 miles west. Fort Belknap was one of the early frontier forts established to protect settlers from Indian depredations. Today, the old fort is a state historical park and one that is well worth visiting.

Crossing the Chihuahuan Desert

— Courtesy Library of Congress —

From Fort Belknap the stage route turned in a more southwesterly direction towards the town of Carlsbad near the Concho River and present-day San Angelo. This area is actually in the northeast corner of the greater Chihuahuan Desert. From here on out to El Paso, locating water would be as great a concern as the Indian threat. A historic highlight of modern-day San Angelo is Fort Concho, a National Historic Landmark founded in 1867. A tour of the site’s 23 historic buildings and museum provides the visitor with a window into frontier life in Texas after the Civil War.

Up to about this point in its journey across Texas, the Butterfield Overland Mail Service made use of stagecoaches that were similar in every way to those that we see today in movies and television. That is, the coaches were constructed with wood sides, doors on each side, and padded seats. These coaches were supported on the chassis by tough leather straps instead of leaf springs, as some might expect. Six or eight horses usually drew the stages.

Often, the horses and mules used to pull the stages were not very well broken to the task at hand. Some stage passengers wrote of experiencing half-broke animals being hooked to the stages and, once all were aboard, being turned loose to tear off as fast as they could run. As one can imagine, some pretty exciting stage wrecks also occurred as a result. All of which points out that stage travel on the frontier was not for the faint of heart.

In this part of the state, due to the rougher terrain found in southwest Texas, Butterfield began using what manufacturers called a stage wagon; and others called it a mud wagon. The stage wagon had open sides and was about 60 percent lighter weight than the stagecoach. In addition to the change in coaches, the terrain also called for the use of mules because of their reputation for toughness and surefootedness. But, according to some early memoirs, the mules weren’t any better broken than the horses. It was often still a wild ride.

In this western part of Texas, the Butterfield also used water wagons to haul water to the stations that did not have a nearby source. In some locations, earthen tanks were dug to provide a supply of water for horses and passengers. In other areas, cisterns were built to hold the water.

West of the Pecos

— Courtesy True West Archives —

From Carlsbad, on the Concho River, the stage line pushed on to the next reliable source of water, the Pecos River. The route crossed the Pecos at the fabled Horsehead Crossing in the general vicinity of the present-day town of McCamey. In those days before flood-control dams, the Pecos River was a real challenge and could only be crossed in certain locations, with Horsehead Crossing being the most commonly used along the southern route. Sadly, today, the exact location of Horsehead Crossing is unknown.

Pushing southwest, the Butterfield’s next stop was at another frontier Army post. This time it was Fort Stockton, located at Comanche Springs, a favorite stop for the Comanches on their raids into Mexico. Fort Stockton, now a thriving west Texas town, is on the east edge of the Big Bend region of the state, so-named because the Rio Grande, south of there, makes a huge bend on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. One of the favorite stops in Fort Stockton was the Annie Riggs Hotel, which still exists and is a very interesting historic site. Don’t miss a tour of Historic Fort Stockton, which is owned by the city and managed by the Fort Stockton Historical Society.

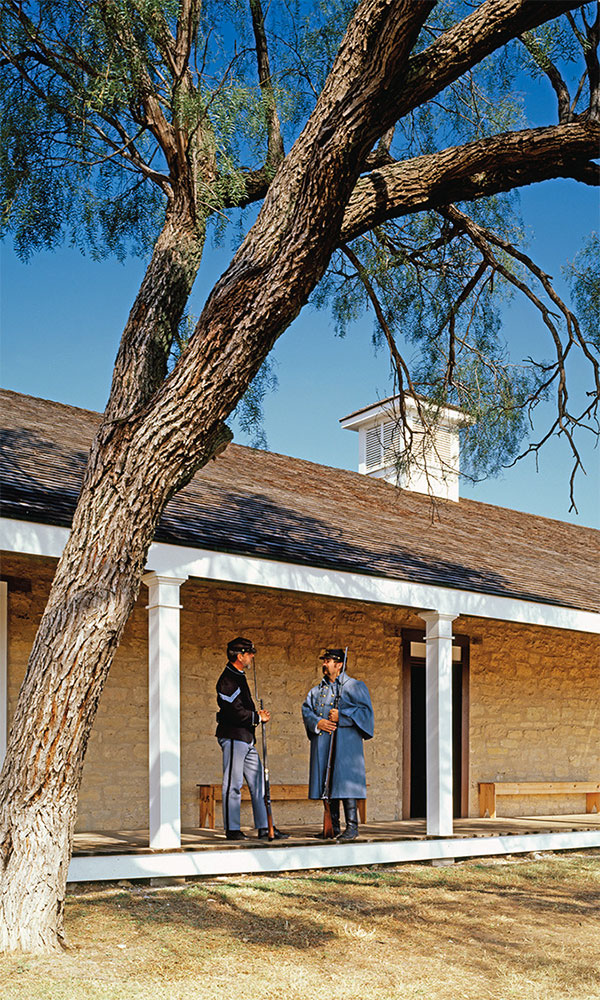

Continuing to push to the Southwest, the mules pulling the stage wagons really began to earn their keep as they climbed into the Davis Mountains and headed for another frontier military post at Fort Davis, some 5,000 feet above sea level. In modern times, this old Army post has been renovated by the National Park Service and managed as a National Historic Site. With regularly scheduled re-enactments and docents in period uniform, Fort Davis is a very popular tourist destination, especially for historians interested in the life and times of a frontier outpost.

West to El Paso

— Watt Casey Jr., Courtesy Albany, Texas, CVB —

From Fort Davis on west, the Butterfield Overland Mail Service tended to travel the same route as our modern Interstate 10. It stopped at Fort Quitman in the southern part of what is now Hudspeth County. Sadly, this is one of the frontier forts that has gone to ruin and is not available for tourist visitation.

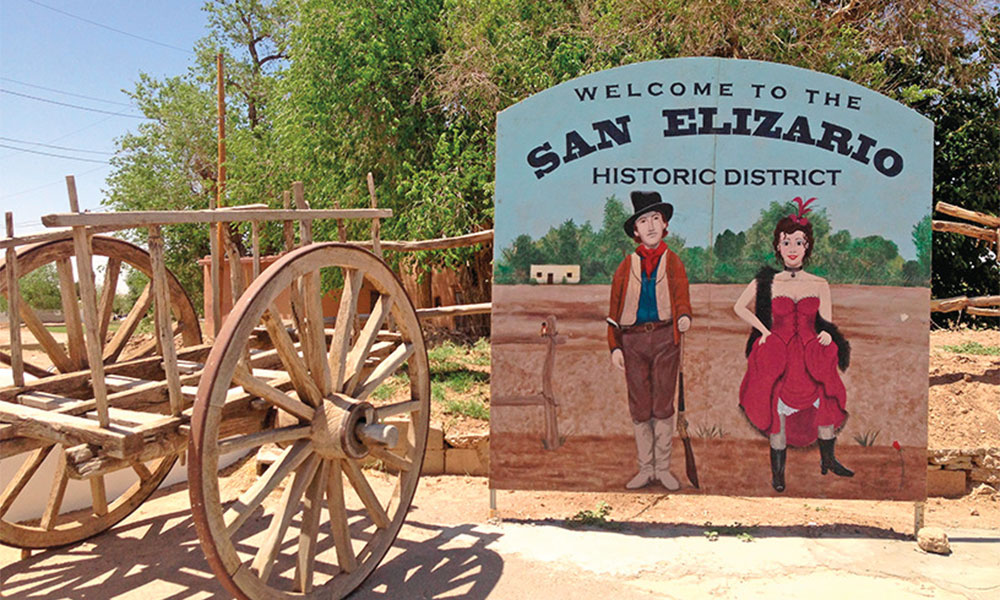

Moving up the Rio Grande, one of the next stops for stage passengers was the village of San Elizario. Today, San Elizario offers historic walking tours of the town and a chance to visit one of the few Butterfield stage stations that still exists. From there it was an easy ride into El Paso. And, at that point, the Butterfield Overland Mail Service left Texas and continued on to San Francisco, across southern New Mexico and Arizona.

– Courtesy VisitElPaso.com –

During its years of operation, the Butterfield made a point of only carrying passengers and the U.S. mail, specifically shunning shipments of money, jewelry or other bullion that would attract stage robbers. For this reason, the company also rarely, if ever, used shotgun guards to ride the stagecoaches, although passengers were encouraged to be armed while traveling through Comanche and Apache country. Surprisingly, the Butterfield boasted that it never had a passenger killed by outlaws or Indians. However, legend has it that they did lose a few customers in stagecoach wrecks.

— Courtesy Texas Tourism —

With the onset of the Civil War, the route of the Butterfield line was moved out of Texas to avoid Confederate confiscation. The Butterfield was absorbed into other companies as time went on. And, with the eventual coming of the transcontinental railroad, all stagecoach service from coast to coast was no longer needed. After that, stagecoaches were only used to get passengers to the nearest railhead, or between towns with no rail service.

Nevertheless, operating from 1857 to 1861, the Butterfield Overland Mail Service became an indelible part of the history of the American West.

Jim Wilson is a retired Texas peace officer, a former sheriff, and a lifelong student of Western history.